By Brandon Friedman

Introduction

Last Friday, 10 March, Saudi Arabia and Iran announced an agreement to re-establish diplomatic ties and re-instate a 2001 security agreement, and a 1998 economic and trade pact. Relations between both sides had been in limbo since 2016, when Riyadh severed ties with Tehran following an Iranian mob’s attack on the Saudi embassy in Iran in 2016. The Kingdom viewed the attack as a response orchestrated by the Islamic Republic in response to its execution of dissident Saudi Shia religious leader Nimr al-Nimr in late 2015.

The rapprochement between both countries grabbed headlines around the world, but despite the hype, it would be premature to characterise it as a breakthrough. It remains to be seen whether the agreement delivers on more than a re-opening of the two countries’ respective embassies in Tehran and Riyadh, but it is potentially significant for three reasons: First, it may herald compromises in the political deadlocks that exist in Lebanon and Yemen, where both Iran and Saudi Arabia have been deeply involved. Greater political stability in Lebanon and Yemen might facilitate economic development in the Eastern Mediterranean and Red Sea sub-regions, both of which have been the focus of much greater regional investment since 2020. Second, it symbolises a new diplomatic role for China in the region and the Gulf, supplanting Russia as the great power alternative to the United States in the region. Third, it raises questions about Saudi Arabia’s confidence in the US’ (and, to a lesser extent, Israel’s) ability to contain and deter Iran’s nuclear development, and protect the Kingdom from what it perceives as Iranian encirclement.

At the 2014 Manama Dialogue, Dr Nizar Madani, then the Saudi Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, said that Iran had a right to be a key player in the region. The Saudis, Dr Nizar said, would welcome Iran as a full-fledged partner, but would need to see it “walk the walk”, and not just “talk the talk.” He referred to an Arabic proverb, “I see you talk, and I like it, and I see you act, and I hate it”. He added that to build trust and full-fledged neighbourly relations, there had to be sustainable ties based on the common principle of not meddling in others’ affairs, and emphasised that the Saudis wanted to see real action, and tangible results, based on this principle. The new deal is thus likely to succeed or fail based on how both countries choose to interpret this standard of mutual non-interference in the affairs of others in the region.

The Regional Rivalry: A Brief History

The Saudi-Iranian rivalry was born out of the 1978-1979 Iranian Revolution, and the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s. The post-9/11 American invasions that toppled the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2001, and Iraq’s Saddam Hussein in 2003, removed threats along Iran’s eastern and western borders and empowered pro-Tehran Shia politicians in Iraq. When Iraq descended into civil war in 2006 and 2007, Saudi Arabia grew concerned that Iran was using the Sunni-Shia violence there to alter the regional balance of power in its favour, upending the status quo based on Sunni supremacy. These fears were exacerbated by Hezbollah’s armed takeover of Beirut in May 2008, and Iran’s rapid nuclear development between 2005 and 2009.

The 2010-2011 Arab uprisings intensified the rivalry. Saudi Arabia rejected Iran’s characterisation of the uprisings as an “Islamic Awakening.” It argued that Iran was using the uprising as a pretext to export its revolutionary politics to Shia communities in the Gulf and beyond. In Bahrain, the Saudis saw Iran as meddling directly in an uprising that ultimately challenged the authority of the ruling Al Khalifa dynasty. The Saudis, with support from the United Arab Emirates, intervened to support the Sunni ruling family in Bahrain against protesters. In Syria, Iran provided direct military and economic assistance to the minority-dominated Alawi government of Bashar al-Assad, helping it suppress the largely-Sunni popular uprising there. Saudi Arabia saw Iran’s role in Syria in 2011-2012 as a replay of Iran’s interference in Iraq following the 2003 US invasion.

At the end of March 2015, the Saudis launched a failed military intervention in Yemen that attempted to roll-back the September 2014Houthi coup d’état. The Houthis are a Zaydi Shia revivalist movement, which perceives the Saudis as historically promoting Salafi Islam — which is hostile to Shia Islam — in northern Yemen. The Saudis viewed the Houthis as an Iranian instrument, which ultimately became a self-fulfilling prophecy after 2015. The Houthis, with Iranian support, have succeeded in escalating attacks on the Saudi home front, using missiles and drones, with increasing effectiveness over the past four years. The Saudi-Iranian rivalry manifested itself in November 2017, when the Saudi Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman, attempted to force Saad al-Hariri to resign as Lebanese Prime Minister, unhappy with his inability to push back against Iran’s influence in Lebanon. But Saudi aggressiveness began to be reined-in when the Trump administration failed to respond to the combined missile and drone attack on Saudi oil facilities at Abqaiq and Khurais in September 2019. The Saudis understood that without American military protection, they were vulnerable, and lacked the means to independently defend the Kingdom from Iran’s mobile missile threat.

2021-2023: The Search for Détente

In 2021, the Biden administration entered office with the goal of using diplomacy to reduce the American military “footprint” in the Middle East. It prioritised finding a quick diplomatic solution for the war in Yemen; reviving the nuclear deal with Iran on an accelerated timeline; and encouraging Saudi-Iranian security dialogue. The first two initiatives proved challenging because of Washington’s ambitious timeline. The Houthis were winning the war in 2021, and appeared unwilling to make diplomatic concessions that would limit their gains. The American push to revive the nuclear deal with Iran was stalled, and the outgoing Rouhani government was constrained by the Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei. However, between April and September 2021, four rounds of talks took place between Iranian and Saudi officials in Baghdad. The talks focused on the war in Yemen, and the political and financial crisis in Lebanon. The last round of talks before China’s involvement took place on September 21, 2021, and they were the first between Saudi Arabia and Ebrahim Raisi’s new government in Iran, which took office in the summer of 2021.

The dialogue broke down between October 2021 and March 2022. In late October that year, a Houthi offensive made significant gains in Maʿrib and Shabwa in Yemen, and threatened to seize the country’s most valuable gas and oil infrastructure. International efforts to freeze the fighting and mediate between both sides floundered. The Houthis were on the march, and seizing the valuable infrastructure would make their state-building project more permanent. The Saudis believed that Hezbollah and Iran were encouraging and lending support to the Houthis in their push to capture Maʿrib. At the end of October 2021, the Saudis abruptly banned imports from Lebanon and expelled the Lebanese ambassador from Riyadh. They were ostensibly responding to comments by the Lebanese Minister of Information, George Kordahi, who, in a televised interview, said that the Houthis were defending themselves against “foreign aggression” in Yemen, alluding to the Saudi military intervention. The Saudi ban denied Lebanon US$250 million in export revenue at a time when its economy was in the grip of a two-year-long systemic crisis. There have been some suggestions that the 2021 Saudi-Iranian dialogue included a quid pro quo: In exchange for Iran reining in the Houthis in Yemen, the Saudis would provide Lebanon with an economic lifeline and facilitate a political compromise. The failure to fulfill this give and take was what led to a breakdown in the Saudi-Iranian dialogue that lasted until April 2022, when talks were renewed for a fifth round.

What changed over the past year that may have contributed to last week’s deal? First, the Houthi offensive in Maʿrib and Shabwa became bogged down, and lost momentum between the end of 2021 and March 2022. Second, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine exacerbated the humanitarian and economic crises in both Lebanon and Yemen. Third, the United Nations succeeded in negotiating a ceasefire between the Houthis and the Yemeni government in April 2022, opening the port of Hudaydah to fuel and food imports to Houthi-controlled areas, a long-standing Houthi demand. The ceasefire was extended twice in 2022, and though it has now expired, the two sides are still enforcing it in practice. Fourth, Hezbollah and its political allies in Lebanon lost their parliamentary majority in the May 2022 elections — the number of seats they controlled dropped from 71 (of 128) in 2018, to 62 in 2022. These circumstances may have set the stage for a renewed effort to find a Saudi-Iranian diplomatic compromise that could help break the political deadlocks in Beirut and Sana’a.

In October 2022, Iran’s Supreme Leader returned to calling for a re-opening of Saudi and Iranian embassies, but there was a new government in Baghdad that was less interested in mediating between the two sides. It was President Xi Jinping’s December visit to Saudi Arabia that reportedly opened the door to China’s role in facilitating the deal. Iran may have also been more receptive to reconciling with the Saudis, given the domestic uprising they have contended with since September, and the increasing isolation they have faced as a result of their military aid to Russia in Ukraine during the past six months.

A major question over the deal is whether it touched on the question of Bashar al-Assad and Syria. Iran and China have much to gain if Saudi Arabia supports the re-integration of the Assad regime into the Arab League, particularly in the wake of the devastating earthquake that rocked Turkey and Syria in February. If Saudi Arabia re-normalises its relations with the Assad regime, it could facilitate the permanent lifting of United Nations sanctions on Syria (in place since 2011), which would allow China to play a role in reconstructing the country and integrating it into the Belt and Road Initiative. With Russia preoccupied in Ukraine, and reducing its presence in Syria, Saudi Arabia may be hoping that China can limit or contain Iran’s influence on the Assad regime.

The China Question

The international media has focused on Beijing’s role in facilitating the Saudi-Iranian deal, which began with Iraqi and Omani mediation, with some arguing that China’s role comes at the expense of the US. Certainly, China’s ability to parlay its influence in Tehran and Riyadh into a role as a regional mediator has elevated its status as a regional power-broker. However, it might make more sense to ask whether China’s role comes at Russia’s expense as the preferred great power alternative to American mediation. Given the active role that Russia played in regional diplomacy from 2012 to 2022 (in Libya, Syria, and Yemen, for example), and Iran’s growing strategic ties with Moscow during the Ukraine War, one might have expected Russia, rather than China, to have brokered this deal — especially since the Kremlin and Riyadh have worked closely in recent years to jointly manage global oil prices in defiance of American pressure.

Key officials in the Biden administration understood that the US was not well-positioned to mediate between Iran and Saudi Arabia, given the nature of Washington’s adversarial history with the former. To make matters worse, the US and Saudi Arabia have been at loggerheads over human rights, weapons sales, and oil production since President Biden took office, raising questions about the level of trust in the bilateral relationship. Despite this, US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, and Daniel Benaim, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, have advocated in the past a regional security dialogue between Iran and Saudi Arabia with support from the US and “other members of the UN Security Council”. They claimed it would be best if such a dialogue was held with American support, but “with no Americans present”. Both viewed a Saudi-Iranian regional security understanding as one of the US’ core goals in the Middle East.

In other words, one does not necessarily need to evaluate China’s role as a Middle East mediator as a zero-sum game in which a Chinese diplomatic success is an American diplomatic failure. The US and China share an interest in protecting global shipping lanes from conflict, and promoting stability in the Gulf in order to avoid further roiling energy markets, which have contributed to inflation and destabilised the global economy. Further, with reward comes risk: China’s increased prestige as a result of brokering this agreement also means its credibility is at stake if there is no follow-through — a real possibility given the history of Saudi-Iranian relations since 1979.

Strategic Convergence Against a Nuclear Iran?

Since the US left the Iran nuclear deal in 2018, there has been some measure of strategic convergence between Tehran’s regional rivals. The September 2020 Abraham Accords were an expression, in part, of a more open strategic alignment between Israel, the UAE, and Bahrain. Saudi Arabia, or at least the Crown Prince, was believed to support working more closely with Israel in constraining Iran’s nuclear programme, and actively resisting its regional expansion.

One question that last week’s deal raises in the US and Israel is whether Saudi Arabia still believes that the US and/or Israel can confront Iran’s march towards nuclear weapons. There is some concern that the Saudis may be asking themselves whether the US and Israel are too preoccupied with Israeli domestic politics and the escalating conflict with the Palestinians to adequately contain Iran’s nuclear progress. If Israel and America are distracted, perhaps the Saudis believe they are better off cutting a deal with Iran that takes Riyadh out of the line of fire? In Israel, there are those who would argue that the deal with Iran demonstrates that Saudis believe the strategic convergence with Israel, symbolised by talk of the Middle East Air Defence network in the summer of 2022, is too much of a liability now that Israel is engulfed in a political crisis, and an escalating conflict the Palestinians. Reports that UAE ruler Mohammed bin Zayed decided to freeze defence acquisitions from Israel in light of recent domestic developments in Israel would seem to reinforce that line of argument.

There is also an important practical question this deal raises for Saudi-Israeli strategic cooperation. In recent years, there have been reports that Riyadh is willing to allow Israel to use Saudi airspace to carry out a prospective military attack against Iran’s nuclear programme. This new deal would seem to preclude that kind of cooperation, however. One could even argue that Iran’s decision to renew ties with Saudi Arabia is a gambit to drive a wedge into the strategic alignment between Israel and Iran’s Arab rivals in the Gulf.

It is premature to draw those kinds of conclusions. There have been reports that among its conditions for normalising relations with Israel, the Saudis have insisted on an American security guarantee, as well as US help in developing a civilian nuclear programme. This suggests Riyadh is pursuing multiple and overlapping strategies to cope with short-, medium-, and long-term regional security challenges. Perhaps more than anything else, what this deal symbolises for Saudi Arabia is a desire to be less dependent on one great power for its protection as it seeks to self-strengthen and become a more independent global and regional power.

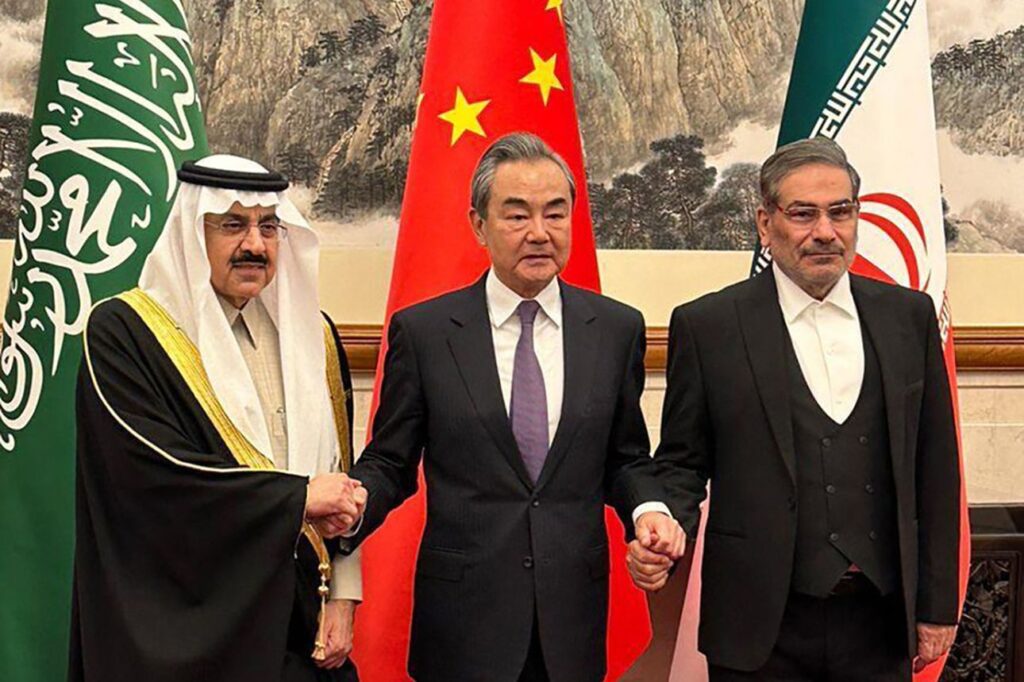

Image Captions: Chinese State Councillor Wang Yi with Saudi Arabia’s National Security Advisor Musaed bin Mohammed Al-Aiban (left) and Iranian national security advisor, Ali Shamkhani, posing for a photo in Beijing on 10 March 2023. Photo: The Henry L. Stimson Center website

About the Author

Brandon Friedman is Director of Research at the Moshe Dayan Center (MDC) for Middle Eastern and African Studies at Tel Aviv University, where he is a member of the Lester and Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities. He is also a non-resident Senior Fellow in the Middle East Program of the Foreign Policy Research Institute (FPRI).