Financial Reporting of Murabaha Contracts: IFRS or AAOIFI Accounting Standards?

By Romzie Rosman[1],  Mohamad Abdul Hamid[2], Siti Noraini Amin[3], Mezbah Uddin Ahmed[4]

Abstract

Financial reporting of Islamic financial transactions is still a subject of unsettled debate among the accountants, auditors and industry observers of Islamic financial institutions (IFIs). In Malaysia, the issues in financial reporting of Islamic financial transactions have been discussed since early 2000 by both academicians and practitioners. The Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) caters to the unique characteristics of the contracts that govern the operations of IFIs, whereas the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) does not have any specific International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) for Islamic contracts adopted by IFIs. However, IFRS are accepted by the majority of the world, including Malaysia. The Malaysian Accounting Standards Board (MASB) has concluded that it would not be in conflict with the Shariah to apply conventional accounting standards, namely the IFRS, for accounting of Islamic financial transactions. Nevertheless, in 2011, the IASB established the Consultative Group for Shariah-Compliant Instruments and Transactions to discuss any issues related to the financial reporting of Islamic financial transactions. This paper reviews and analyses the two main underlying issues in adopting IFRS as compared to AAOIFI accounting standards, which are substance over form and the time value of money, concerning recognition, measurement and disclosure requirements in the financial reporting of a murabaha contract. This paper also compares financial reporting presentation and the disclosures of Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad (BIMB) and ABC Islamic Bank, examples respectively of IFRS and AAOIFI FAS based reporting entities. The findings of this paper provide a basis for the inclusion of the substance over form and the time value of money in financial reporting of the Murabaha contract.

Keywords: AAOIFI, IFRS, financial reporting, Islamic financial institutions, murabaha.

Introduction

The Asian-Oceanian Standard-Setters Group (AOSSG) (2015) revealed that national standard-setters generally view specialized Islamic accounting standards as incompatible with the objective of convergent of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). A previous study by the AOSSG (2010) showed that there are significant differences between the IFRS and the Financial Accounting Standards (FAS) issued by the AAOIFI. The study also argues that in jurisdictions where Shariah interpretations support an approach that differs from IFRS requirements, standard-setters may have to review such interpretations and allow or require departures from those requirements for Islamic financial transactions. They conclude that although IFRS is an attempt to be the globally accepted single set of standards, there is resistance by those who believe that some IFRS principles are irreconcilable with their interpretations of Shariah.

Issues of the Accounting Principles

The AOSSG (2010) has examined two contrasting views on how to account for Islamic financial transactions: (i) a separate set of Islamic accounting is required; or (ii) IFRS can be applied to Islamic financial transactions. Accordingly, the differing approaches to accounting for Islamic financial transactions can be generally be attributed to opposing views on two main underlying issues which are: (i) the conventional approach of recognising and measuring the economic substance of a transaction, rather than its legal form; and (ii) the acceptability of reflecting a time value of money in reporting an Islamic financial transaction. However, the Malaysian Financial Reporting Standards (MFRS),[5] which serve as the basis for financial reporting in Malaysia, have been rendered fully convergent with the IFRS since 1st January 2012 (Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM), 2016). In para 8.1 of the BNM policy document, it states:

Pursuant to section 74 of the IFSA [Islamic Financial Services Act 2013], a licensed person shall ensure that financial statements are prepared in accordance with the MFRS and shall disclose a statement to that effect in the financial statements.

A footnote of the policy document further states that:

In line with the MASB’s consultative approach, a licensed person is to refer to MASB when there is divergence in practices regarding the accounting for a particular Shariah compliant transaction or event, or when there is doubt about the appropriate accounting treatment and the licensed person believes it is important that a standard treatment be established.

Moreover, the policy document highlights that the licensed person should take into account the differences between Islamic banking transactions and conventional banking transactions which may arise from the application of the Shariah contracts that involve trade-related transactions, partnership-related transactions, and profit and loss sharing transactions. The accounting of each Islamic transaction is to be viewed closely to determine the most appropriate treatment, taking both the Shariah and economic effects of such transactions into account. Furthermore, the policy document in Para 8.3 states that a licensed person shall comply with the resolution of the Shariah Advisory Council (SAC) of BNM on the applicability of the following accounting principles adopted in the MFRS as being consistent with the broader view of Shariah principles:

Accrual basis: The effect of a transaction and other events is recognised when it occurs (and not as cash or its equivalent is received or paid) and is recorded in the accounting records and reported in the financial statements of the periods to which it relates.

Substance over form: The “form” and “substance” of the transaction must be consistent and shall not contradict one another. In the event of inconsistency between “substance” and “form”, the Shariah places greater importance on “substance” rather than “form”.

Probability: The licensed person is to consider the degree of uncertainty of the future economic benefits associated with the transaction in the reference to the recognition criteria.

Time value of money: In a transaction involving time deferment, the asset (liability) is carried at the present discounted value of the future net cash inflow (outflow) that the transaction is expected to generate in the normal course of business. The application of the time value of money is permissible only for exchange contracts that involve deferred payment and is strictly prohibited in loan transactions (qard).

Hence, it is important to revisit the issues highlighted earlier on the different views of the underlying principles used between the MASB (IFRS-compliant) and the AAOIFI in general and then provide some illustration on the reporting of Islamic financial transactions. The next section discusses in brief the experience of Malaysia in the accounting and reporting of Islamic financial transactions.

Research Methodology

This paper reviews and compares the financial reporting based on the MASB and the AAOIFI standards by selected IFIs in Malaysia and Bahrain, with an examination of comparative recognition, measurement, and disclosure requirements for murabaha contracts. The review focuses on two main opposing views by the two standard-setters in the financial reporting of Islamic financial transactions, which are (i) the conventional approach of recognising and measuring the economic substance of a transaction, rather than its legal form; and (ii) the acceptability of reflecting a time value of money. The review of these points will facilitate a faithful and transparent financial reporting of the murabaha contract.

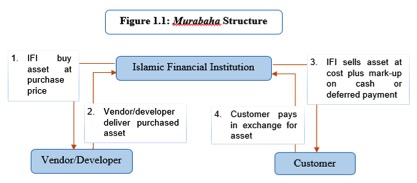

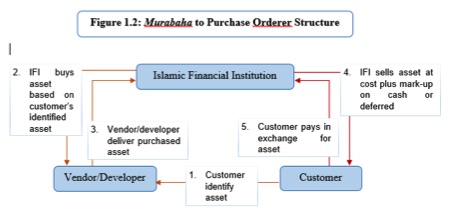

Murabaha Structure and Type

The murabaha contract is a true sale-based contract between two contracting parties to acquire a specified asset excluding monetary assets such as debt, and the cost and mark-up must be disclosed to the purchaser in the selling price (ISRA 2012). The IFIs should bear risk in the trade by being responsible for the murabaha assets prior to their sale and actual delivery to customers (Abdul Rahman 2010). AAOIFI via Financial Accounting Standard 2 (FAS 2) classifies two types of murabaha arrangements: (i) murabaha, where an Islamic financial institution sells assets to a willing purchaser and, (ii) murabaha to the purchase orderer, where an Islamic financial institution acquires an identified asset by the orderer (customer) who promises to buy from the IFIs at specified cost plus mark-up. The IFIs then execute the murabaha contract to conclude the sale and purchase of the identified asset with the orderer. Below are the illustrations of the generic structures of the murabaha and the murabaha to purchase orderer as classified by the AAOIFI:

Financial Reporting of the Murabaha Contract

Recognition of the Murabaha Contract

The IASB in its Framework for the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Statements defined recognition as “the process of incorporating in the statement of financial position and income statement an item that meets the definition of an element” (i.e., asset, liability, equity, income or expense). The underlying principles of IFRS require consideration of the economic substance of a transaction rather than the legal form of a contract in recognition of an item or element in the financial position and income statement. The point is that “substance over form” is considered faithful representation of the economic behaviour, and is deemed to be an inherent part of it (ISRA 2012). Further to this principle, IFRS had since published two different standards relating to financing and trading arrangements. The discussion by the IASB Consultative Group on Shariah-Compliant Instruments and Transactions in its minutes of second meeting on 5 September 2014 further highlights the relevant IFRS to be applied for the murabaha contract. For instance, IFRS 9 Financial Instruments[6] is applicable when the economic substance of the murabaha contract is classified as a financing arrangement. On the other hand, IFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers[7] is applicable when the economic substance of the murabaha contract is classified as a trading arrangement.

The second type of murabaha contract classified by AAOIFI is widely practised by today’s IFIs (ISRA 2012). They acquire an asset only when there is a demand and promise to purchase the asset by a customer. Therefore, the IFIs do not actually hold the murabaha asset as inventory. The murabaha structure is merely to facilitate the financing of the desired asset through the purchase and sale of a murabaha asset (commodity). The structure directly defines the customary business of an Islamic financial institution as a financier instead of trader. Thus, it was concluded that the economic substance of the transaction is financing, based on the main objective of the contract concluded between the IFIs and the customers, and not the processes of sale and purchase of the murabaha asset in the contract┬á(IASB Consultative Group on Shariah-Compliant Instruments and Transactions 2014). Thus, the applicable accounting standard to reflect murabaha financing as the economic substance of the transaction is IFRS 9, which requires the Islamic financial institution to recognise the right to receive cash flows from the murabaha contract as a financial asset in the statement of financial position.

The AAOIFI appears to be ambiguous about its views on substance over form (AOSSG, 2010). The Statement of Financial Accounting 1 (SFA 1) AAOIFI acknowledges that it is necessary for the transactions to be accounted for and presented in accordance with its economic substance as well as the legal form. In addition, the SFA 2 AAOIFI Para 111 states that “.reliability means that based on all the specific circumstances surrounding a particular transaction or event, the method chosen to measure and/or disclose its effects produces information that reflects the substance of the event or transaction,” which appears to support the substance of the transaction. However, the application of FAS 2 AAOIFI Murabaha and Murabaha to the Purchase Orderer requires the murabaha contract to be treated as a trading instead of financing arrangement, thereby suggesting that AAOIFI gives priority to the legal form of the contract over the substance of the transaction. Clearly the consideration is based on the purchase and sale of the murabaha asset that was concluded between the Islamic financial institution and the customer, and not the customary business of an Islamic financial institution as a financial intermediary whereby the main objective of the contract concluded is to facilitate financing of a desired asset by the customer. In order to reflect the trading arrangement, the FAS 2 AAOIFI recognises inventory risk attached to the murabaha asset prior to resale to the customers, as well as the legality of binding promises requiring the Islamic financial institution to disclose the obligation of promises made in the sale of murabaha to the purchase orderer. The FAS 2 AAOIFI also recognises a murabaha receivable as an asset in the statement of financial position, and any unearned deferred profits shall be offset against the murabaha receivables.

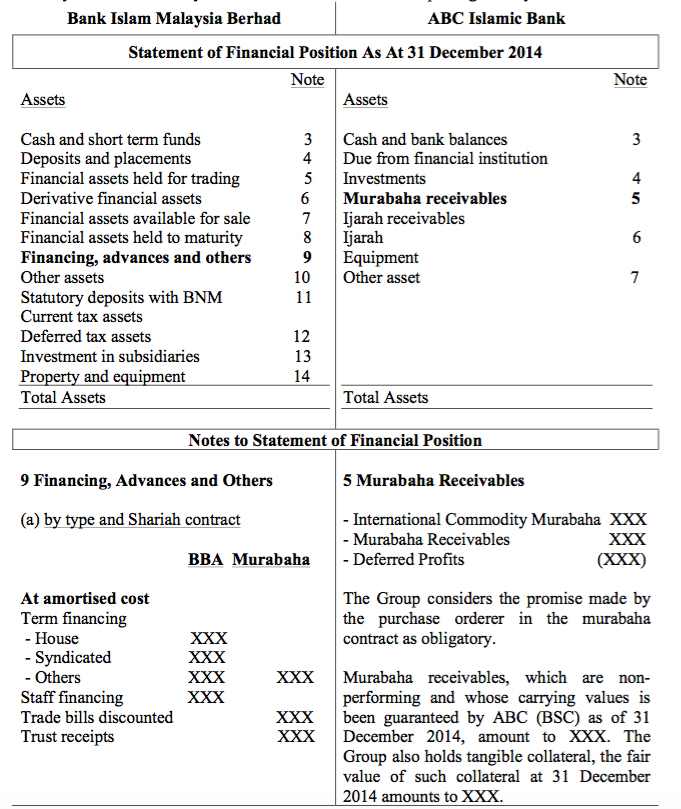

This paper only reviews the comparable IFRS standard in accordance to economic substance that is widely practised by IFIs in Malaysia against the AAOIFI standard. In this case, the comparable standards are IFRS 9 against FAS 2 AAOIFI. Appendix 1 illustrates the comparative recognition of murabaha asset in the statement of financial position of IFIs that applies the MASB (IFRS-compliant) and the AAOIFI. To summarise the difference, Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad of Malaysia (BIMB), which applies IFRS 9, recognised murabaha contracts as financial assets in its statement of financial position to reflect the customary business of BIMB as a financial intermediary and murabaha as a financing arrangement. On the other hand, ABC Islamic Bank of Bahrain applies FAS 2 AAOIFI and recognises murabaha receivables in its statement of financial position to reflect the legal form of the contract as a murabaha trading arrangement.

Measurement of a Murabaha Contract

The measurement of a murabaha contract is also at issue. SFA 2 AAOIFI Para 7 clearly states the time value of money to be an example of a concept that is inconsistent with Islamic Shariah. The SFA 2 AAOIFI Para 8 also emphasises that in accordance with Shariah, money does not have a time-value aside from the value of goods that are being exchanged through the use of money. However, a majority of Muslim scholars have recognised consideration of the time value of money as an element in murabaha profits, to uphold justice between the contracting parties (deferred price should be higher than the spot price to strike a balance of benefit over future consumption) (ISRA 2013). The SAC of BNM in its 71st meeting, dated 26 & 27 October 2007, resolved that the application of the time value of money in Islamic financial reporting is permissible only for exchange contracts that involve deferred payment, and prohibits it for deferred repayment of a loan (BNM, 2010).Thus, the MASB concluded, as noted earlier, that it would not be in conflict with Shariah to apply IFRS for financial reporting of IFIs.

IFRS 9 Para 5.1 constitutes initial measurement of financial assets (excluding those with a significant financing component[8]) at acquisition at fair value plus or minus. In the case of a financial asset acquired not at fair value through profit or loss (FVPL), the asset shall be measured by transaction costs that are directly attributable to its acquisition. For subsequent measurement, IFRS 9 Para 5.2 states that the acquired financial asset shall be measured at amortised cost[9] or fair value through other comprehensive income (FVOCI) or FVPL. With reference to IFRS 9 Para 4.1, the classification of financial assets for subsequent measurement are as follows; (i) a financial asset is measured at amortised cost if it is held to collect contractual cash flows that solely represent payments of principal[10] and interest[11] on the principal amount outstanding; (ii) a financial asset is measured at FVOCI if it is held to collect contractual cash flows that solely represent payments of principal and interest on the principal amount outstanding, and selling financial assets; (iii) a financial asset is measured at FVPL if it does not meet criteria of amortised cost or FVOCI. However, regardless of the business model, an entity can elect to measure at FVPL if by doing so it will reduce or eliminate a measurement or recognition inconsistency (accounting mismatch). The impairment requirements also shall apply to financial assets that are measured at amortised cost and FVOCI.

From the above, it can be concluded that the subsequent measurement for financial assets is reliant on the objective of the entity’s business model in holding the financial asset and their contractual cash flow characteristics (PwC 2014). Hence, assessment of the business model and contractual cash flow characteristics of a murabaha contract needs to be performed to determine whether to apply amortised cost or FVOCI or FVPL for subsequent measurement of the contract. The classification of a murabaha contract as financing arrangement in light of its economic substance, as discussed earlier, met the first condition of business model assessment, where the murabaha contract is concluded with the objective of collecting the contractual cash flows from the financial asset. Next, concerning whether the contractual cash flows represent payments solely of principal and interest on the principal amount outstanding, IFRS 9 establishes that financial assets with contractual cash flows that are solely payments of principal and interest on the principal amount outstanding are consistent with a basic lending arrangement, where consideration for the time value of money and credit risk[12] are typically the most significant elements of interest. The characteristics of contractual cash flows in murabaha contracts appear to be similar to basic lending arrangements because of the allocation of murabaha profits. The legitimacy of murabaha profits is based on the exchange contract and underlying asset (ISRA 2013). Moreover, the application of credit risk in considering murabaha profits is in parallel with the Islamic theory of profit, which recognises risk as one of the elements in profit determination (Rosly 2005). Provision for the risk of default is attached to the financial asset held during the deferred payment duration. Both the business model and contractual cash flows of the murabaha contract meet the conditions for subsequent measurement of financial asset at amortised cost.

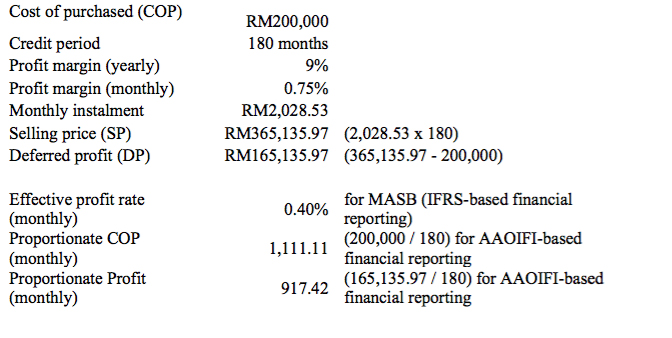

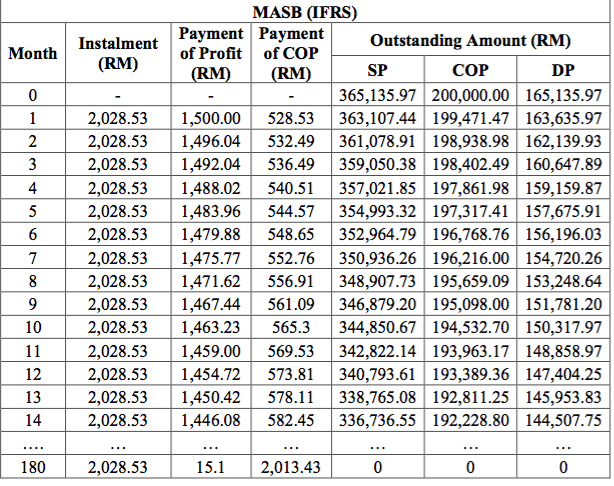

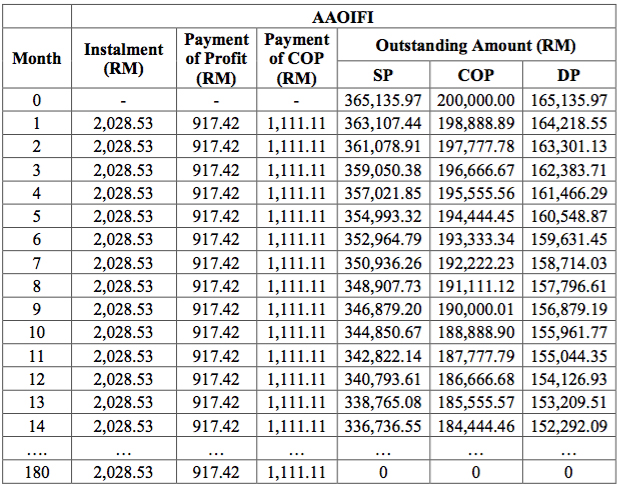

IFRS 9 para 5.4 requires amortised cost measurement to apply the effective interest method[13] which shall be calculated by applying the effective interest rate to the gross carrying amount of a financial asset except for credit-impaired financial assets. IFRS 9 defines the effective interest rate as the rate that exactly discounts estimated future cash payments or receipts through the expected life of the financial asset or financial liability to the gross carrying amount of a financial asset or to the amortised cost of a financial liability. IFRS 9 further explains that when calculating the effective interest rate, an entity shall estimate the expected cash flows by considering all the contractual terms of the financial instrument (for example, prepayment, extension, call and similar options) but shall not consider the expected credit losses[14]. Under this method, the murabaha profit allocation is calculated based on the effective profit rate against the principal amount outstanding, which subsequently will be deducted from instalments paid by the customers. Then, the balance will be set off against the principal amount outstanding. Appendix 2 illustrates the modus operandi of the effective profit method and the profit allocation reducing trend (reported profit higher in the earlier years and lower in the later years) against the principal balance set off in a rising trend (reported principal balance set off lower in the earlier years and higher in the later years).

The profit allocation reducing trend raises controversy about risk-sharing and fairness between the Islamic financial institution and customers. The higher allocation of profit to IFIs at earlier stages of the deferred duration seems to suggest a lack of trust in the customer’s capability to make future payments. It may represent the intention of IFIs quickly to compensate for the profit risk attached to the financial asset, so that in the event of default, they may not have to incur such huge losses from the unearned profits, and at the same time customers are liable for a greater sum of the outstanding principal compared to AAOIFI. Furthermore, the concept of the time value of money and effective interest rates raises concerns about discounting receivables and imitating traditional interest-based financing arrangements, since according to Shariah money does not have a time value aside from the value of goods┬á(Uddin and Rosman 2015).

Measurement of the murabaha contract by FAS 2 AAOIFI requires measurement for the murabaha assets (inventory) and murabaha receivables to reflect trading arrangements, which carries inventory risk and binding promises. At initial measurement, the FAS 2 AAOIFI requires a murabaha asset to be recognised at historical cost[15]. The subsequent measurement relies on the obligation of the purchase orderer to fulfil the purchase promise. If the purchase orderer is not obliged to fulfil the purchase promise as defined by the IFIs, the murabaha asset shall be measured at cash equivalent value[16] or net realisable value, if there is an indication of non-recovery of the costs (FAS 2, Para 4). A provision is also required for decline in asset value, to reflect the difference between acquisition cost and the cash equivalent value. On the other hand, if the purchase orderer is obliged to fulfil the purchase promise as defined by the IFIs, murabaha asset shall be measured at historical cost unless there is a decline in value due to damage, destruction, or other unfavourable circumstances, in which case valuation to reflect the decline in asset value is to be measured at the end of the financial period (FAS 2, Para 3).

Upon financing the customer, the murabaha receivables shall be recorded at the time of occurrence at their face value, and be measured at the end of the financial period at their cash equivalent value (amount due less any provision for doubtful debts) (FAS 2, Para 7). At initial measurement, murabaha receivables at face value represent the selling price (cost plus murabaha profits) of the murabaha asset to the customers. In contrast with IFRS 9, AAOIFI adopts the proportionate allocation of profit over the period of the credit whereby each financial period shall carry its portion of profits irrespective of whether or not cash is received. FAS 2, Para 9 requires for deferred profits received from customers to be deducted from murabaha receivables in the statement of financial position. The proportionate method recognises murabaha profit over the deferred period without consideration of time value of money as a measurement attribute. Even though the cumulative profit earned from adoption of AAOIFI and IFRS is equal, the reported profit earned across the financial period shall be different. Appendix 2 illustrates the differences in profit allocation between AAOIFI and IFRS. At end of the 14th month, due to different measurements adopted, the MASB (IFRS-compliant) allocated profit is RM1,446.08, whereas it was only RM917.42 for AAOIFI. The outstanding amount of deferred profit for MASB (IFRS-compliant) was RM144,507.74, considerably less than the RM152,292.09 remaining in AAOIFI’s profit allocation. The outstanding principal in MASB accounting exceeds that of AAOIFI by the same amount, RM7,784.35. The illustration from Appendix 2 suggests that the proportionate method better upholds the risk-sharing and fairness between the IFIs and customers, as the profit is recognised consistently throughout the deferred period. There is no issue as in MASB of collecting higher profits at earlier periods to minimise the exposure to credit default or unearned deferred profits.

Disclosures of Information about Murabaha Contracts

Notes to the statement of financial position of selected Islamic banks under Appendix 1 illustrate that both the MASB-IFRS compliant and AAOIFI standards require qualitative and useful information on murabaha contracts to be disclosed and explained. The main differences are on what and how the useful information is disclosed and presented. BIMB disclosed the method of financial asset measurement as well as all the types and amounts of Shariah financing contracts, including murabaha, in the statement of financial position. This is to adhere to the requirements stated in the IFRS 7 Financial Instruments: Disclosure (requires an entity to provide qualitative disclosures in the notes to the financial statements), and IFRS 9 (outlines the transition disclosure requirement if there are changes in the application of the financial asset measurement category as well as carrying amount).

Alternatively, the ABC Islamic Bank disclosure focused on the items incorporated in the murabaha receivable, such as deferred profit, the obligation on promise to purchase made in the murabaha to the purchase orderer, the guaranteed carrying value for non-performing murabaha receivables, and the amount of tangible collateral to murabaha contracts. The bank thereby adheres to the requirement stated in the SFA 2 of AAOIFI, Para 130 that adequate disclosure of all material information that is useful to the users in their decision making be included in the financial statements, the notes accompanying them or in additional presentations. It also adheres to the FAS 2 of AAOIFI, Para 16 that requires disclosure on consideration of the promise made in the murabaha to the purchase orderer as obligatory or not in the notes to the financial position. The standard also requires that Financial Accounting Standard 1 General Presentation and Disclosure in the Financial Statements (FAS 1) be observed, such as disclosing accounting policies adopted that are not consistent with the concepts of financial accounting for Islamic banks, and earnings or expenditures prohibited by the Shariah.

Conclusion

Generally, both IFRS and AAOIFI aim to provide transparent and faithful presentation and disclosure of useful information to the users of financial statements. This is to satisfy the needs and accountabilities of the stakeholders, who require IFIs to develop specific presentations and disclosures by taking into consideration the Shariah requirements (Abdul Rahman 2010). For instance, Malaysia developed MASB Technical Release (Tri-3) to serve as guiding principles in considering the unique characteristic of Islamic financial transactions (Abdul Rahman 2010). Although it is notable that the AAOIFI standards uniquely cater to the characteristics of Islamic financial transactions, the survey made by Islamic Finance Working Group of AOSSG in 2013 noted that the jurisdictions that adopted AAOIFI FAS also applied IFRS in financial reporting, in cases where AAOIFI is silent. There are also cases which reveal the inadequacy of IFRS in catering to the unique characteristic of Islamic financial transactions. In the case of the murabaha contract, the financial reporting objectives can be achieved by disclosing greater information in the notes accompanying the financial statements.

References

Abdul Rahman, A.R. (2010). An introduction to Islamic accounting: Theory and practices. CERT Publications Sdn Bhd. Kuala Lumpur. Malaysia.

Accounting Auditing Organisation for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) (2010). Financial Accounting Standard 2. Murabaha and Murabaha to the Purchase Orderer. Manama, Bahrain.

Accounting Auditing Organisation for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) (2010). Statement of Financial Accounting 1. Objectives of Financial Accounting for Islamic Banks and Financial Institutions. Manama, Bahrain.

Accounting Auditing Organisation for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) (2010). Statement of Financial Accounting 2. Concepts of Financial Accounting for Islamic Banks and Financial Institutions. Manama, Bahrain.

Asian-Oceanian Standard-Setters Group (AOSSG) (2010). Financial reporting issues relating to Islamic finance. Accessed via www.aossg.org

Asian-Oceanian Standard-Setters Group (AOSSG) (2015). Financial reporting by Islamic financial institutions: A study of financial statements of Islamic financial institutions. Accessed via www.aossg.org

Asian-Oceanian Standard-Setters Group (AOSSG). About Us. Accessed via www.aossg.org

Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) (2010). Shariah Resolution in Islamic Finance. Accessed via http://www.bnm.gov.my

Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) (2016). Financial reporting for Islamic banking institutions. Accessed via http://www.bnm.gov.my

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) (1989). Framework for the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Statements. London. United Kingdom.

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) (2014). IASB Consultative Group on Shariah-Compliant Instruments and Transactions (2014, September). Kuala Lumpur. Malaysia.

IFRS Foundation (2015). International Accounting Standard 15. Revenue from Contracts with Customers. London. United Kingdom.

IFRS Foundation (2015). International Accounting Standard 9. Financial Instruments. London. United Kingdom.

International Shariah Research Academy for Islamic Finance (ISRA) (2012). Islamic Financial System: Principles & Operations. Kuala Lumpur: Pearson Custom Publishing.

International Shariah Research Academy for Islamic Finance (ISRA) (2013). An appraisal of the principles underlying International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS): A Shariah perspective ÔÇô Part I. 54/2013.

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey Bass. San Francisco. CA.

PricewaterhouseCoopers (2014). In depth a look at current financial reporting issues: IFRS 9 ÔÇô classification and measurement. Accessed via www.pwc.com.

Rosly, S.A. (2010). Critical issues on Islamic banking and financial markets. Dinamas Publishing. Kuala Lumpur. Malaysia.

Uddin, M. & Rosman, R. (2015, March). Financial reporting for Islamic financial institutions in Malaysia: Issues and challenges. Islamic Finance Review, 5 (1), 52 ÔÇô 53.

Appendix 1 ÔÇô Statement of Financial Position & Notes

Source: Extracted from respective statements of financial position.

Available at www.bankislam.com.my and https://www.bankabc.com/world/IslamicBank/En/Pages/default.aspx

Appendix 2 ÔÇô Profit Allocation

[1] Romzie Rosman is an Assistant Professor in Universiti Islam Malaysia. He can be contacted at romzie@uim.edu.my.

[2] Mohamad Abdul Hamid is a Professor in Universiti Islam Malaysia.

[3] Siti Noraini Amin is a post-graduate student in the International Centre for Education in Islamic Finance.

[4] Mezbah Uddin Ahmed is an Associate Researcher in the International Shari’ah Research Academy for Islamic Finance.

[5] MASB subscribes IFRS by IASB and issued IFRS-compliant MFRS in November 2011, in respect of its application in Malaysia.

[6] Issued in July 2014 and supersedes IAS 39 Financial Instruments ÔÇô Recognition and Measurement.

[7] Issued in May 2014 and supersedes IAS 18 Revenue.

[8] A contract contains a significant financing component when an entity adjusts the promised amount of consideration for the effects of the time value of money as agreed by both parties on timing of payments (either explicitly or implicitly) that provides any significant benefit of financing the transfer of goods or services to the customer. A significant financing component may exist regardless of whether the promise of financing is explicitly stated in the contract or implied by the payment terms agreed to by the parties to the contract (IFRS 15).

[9] Amortised cost is the amount at which the financial asset is measured at initial recognition minus the principal repayments, plus or minus the cumulative amortisation using the effective interest method of any difference between that initial amount and the maturity amount and, adjusted for any loss allowance (IFRS 9).

[10] Principal is the fair value of the financial asset at initial recognition. However, that principal amount may change over the life of the financial asset (for example if there are repayments of principal) (IFRS 9).

[11] Interest consists of the consideration for the time value of money and credit risk associated with the principal amount outstanding during a particular period of time and for other basic lending risks (for example, liquidity risk) and costs (for example, administrative costs) associated with holding the financial asset for a particular period of time, as well as a profit margin that is consistent with a basic lending arrangement (IFRS 9).

[12] Credit risk is the risk that one party to a financial instrument will cause a financial loss for the other party by failing to discharge an obligation (IFRS 7).

[13] The effective interest method is the method that is used in the calculation of the amortised cost of a financial asset or a financial liability and in the allocation and recognition of the interest revenue or interest expense in profit or loss over the relevant period (IFRS 9).

[14] The expected credit losses is the weighted average of credit losses with the respective risks of a default occurring as the weights.

[15] The purchase price or acquisition cost of the asset and any other related expenses incurred by the Islamic financial institutions at asset acquisition. For instances, customs duties and other purchase taxes, transport and loading charges, insurance.

[16] The no. of monetary unit that would be realised as of the current date (SFA 2, Para 89).