By David Mednicoff

Few political ideals of potentially universal sweep are left in the early 21st century, yet the rule of law is one of them. As Brian Tamanaha, among others, has argued, the rule of law is the pre-eminent political ideal in the world today, without agreement upon precisely what it means. (2004, 4, emphasis in original) This basic insight has generated both intellectual and practical work around clarifying what the rule of law might mean in theory and practice, including my large project grounded in recent Gulf Arab sociopolitical experience. This brief essay examines why precision on the rule of law is hard to come by and reviews some significant aspects of the literature on the topic, as a means for grounding the importance of specific work on how aspects of the rule of law work in particular places and contexts.

As with many important global concepts, international bodies have tried to define the rule of law in a manner that can be seen as portable and consistent. The definition employed by the United Nations, coming from former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, is only quasi-official, but is used frequently nonetheless. This definition is:

a principle of governance in which all persons, institutions and entities, public and private, including the State itself, are accountable to laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced and independently adjudicated, and which are consistent with international human rights norms and standards. It requires, as well, measures to ensure adherence to the principles of supremacy of law, equality before the law, accountability to the law, fairness in the application of the law, separation of powers, participation in decision-making, legal certainty, avoidance of arbitrariness and procedural and legal transparency.[1]

The UN definition begins to suggest the problems in being precise around the rule of law’s meaning, because it embraces both a principle, that is, a single or set of political norms, and on the other hand specific institutional mechanisms for trying to realize these norms. Central to the slipperiness of the rule of law’s meaning is that it is used, often in the same document, to refer to two distinct dimensions, the dimension of values and ideals, and the dimension of institutions and enforcement mechanisms. I suggest that the additional dimension of where rule of law ideas come from matters. This has two components, the question of how religious and secular inspiration might shape the rule of law, and what mix of the transnational, national and subnational dominates rule-of-law advocates and enforcement mechanisms in a particular legal context.

In short, the rule of law needs to be looked at in terms of what basic values or norms it suggests, where those norms come from, and what institutional forms it takes.

What do we know and need to know about how these different facets of the rule of law are understood in the contemporary sociopolitical world?

Rule of law values

In common parlance, even within a particular society the rule of law is invoked to stand for a variety of phenomena, often conflicting. Most obviously, lawyers, judges and scholars typically focus on the pre-eminence of law over particular leaders, including respect for judges’ decisions or the primacy of constitutional norms. At the same time, the rule of law can obviously mean order and ordinary citizens’ obedience to law, relating more to enforcement and even the authoritarian elements of a particular political system. Basic conflicts of this nature underscore how contested, and important, the term is.

What the rule of law might mean as a norm, or most likely a set of norms, has received some systematic academic attention. Not surprisingly, this attention comes largely from the vantage point of political philosophy and jurisprudence emanating from Western Europe and North America, which received privileged positions through colonial, and post-colonial Western political and cultural hegemony.

In this context of Europe and North America, a lot of work has been produced on the meanings of the rule of law and its optimal connections to politics. Much of this can be traced back to European theory like Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws (1748) and Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835), and perhaps even further to Greek political philosophy. The emphasis of the first on constitutions and the second on legal institutions presaged a general predisposition in more contemporary research towards formal legal texts and mechanisms as central to specifying and maintaining the rule of law.

In the dominant Western tradition, the signal features of the rule of law, when they are delineated, are that it is not arbitrary, that it applies to all members of a society, including the powerful, and that it is adjudicated through courts and judges (e.g., Dicey 1885). A more contemporary version of the core elements of the rule of law includes codified rules that are made by a representative government, available to and applicable to everyone, and adjudicated by judges or courts (e.g., Bingham 2011). Yet these concepts are all potentially ambiguous, and contestable, and not uniformly present in the West (e.g., Kleinfeld 2012; Tamanaha 2004).

Yet the question of meanings becomes more complex when contexts beyond Western Europe are considered, with all of the diversity of global religio-cultural, linguistic and political history.  Indeed, terms and meaning clusters around the rule of law differ across Anglo-American, French and German borders. Once the world more generally is surveyed, every country, and even sometimes sub-national units, is a mosaic of differing influences and plural meaning clusters. One generalization that might be ventured is that an idea derived from Anglo-American particular history of robust judicial review in a common law system, that fixed law is supposed to trump particular political authority, may be less of a core meaning of the rule of law in many societies with different histories around the need for stable political order or social harmony.

Varied meanings of the rule of law get even more complex when countries’ diverse ideological and historical political influences come into play. In trying to analyze legal norms in a particular society, it is important to steer clear of cultural essentialism. Yet the interplay of religious and non-religious legal traditions and legal authority helps make sense of the rule of law’s set of meanings in a particular society, as the data my research team and I collected around Islamic and non-Islamic meanings of the rule of law as part of the Rule of Law in the GCC project[2] suggest. For example, the primacy of religious scholars as legislative reference points in traditional Islamic legal governance, and the vulnerability to push-back and challenges to legal institutionalization from authoritarian Middle Eastern and colonial rulers that affected this system make sense of the importance of and challenges to shari’a as a source of legitimacy for the rule of law in many Arab states.

A nuanced look at the political history of plural legal norms in Arab states, then, would acknowledge the willful authoritarian pressures against a fluid tradition of quasi-judicial guidance, the hollow nature of European legal ideals when juxtaposed with the reality of colonial practice, and the high level of movement among laws and legal scholars throughout the Mediterranean, African and Asian trade routes. All of the above helps explain and visualize not only the enduring importance of Islamic law as a somewhat loose reference point, but the occasional hostility to Western-inspired international law and other legal developments, which we observed in our data from Qatar and Kuwait.[3]

More generally, getting a specific sense of the meaning clusters for the rule of law requires both historical and contemporary analysis in order to map out the ideological sources, content and particular actors who have helped shape the basic contours of the term in a given society. To the extent that this analysis is done at all, it frequently appears in lawyers’ and socio-legal scholars’ readings of constitutions and higher court opinions, whether in one society or in comparative perspective. As important, and still early (e.g., Hirschl 2014) as this work is, it doesn’t necessarily get to broader discussion of the rule of law in social segments outside of key foundational legal documents and courts, and doesn’t really reach countries that have little history of judicial review or other constitutional jurisprudence, such as many countries in Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

Moreover, there is an additional analytical challenge in that conceptions of the rule of law often link to social scientific arguments about sociopolitical outcomes. To take a simple example, to the extent that the rule of law signifies order and effective law enforcement, we might assert that societies in which the rule of law is strong would have low crime rates. This assertion would be less obvious if the rule of law was defined primarily as individual rights.

Among the reasons for the popularity of the rule of law as a norm or set of norms among political elites and policymakers in recent decades is the sense that its positive connotations would likely somehow translate into more stable or more democratic politics where it is present, picking up from the core of Tocqueville’s argument.

However, even in Europe and common law countries, where comparative discussion of legal institutions and ideas is well-developed, it is challenging to state conclusively how the rule of law might enhance political growth and social stability. Outside of the US and Europe?, alternative, sometimes overlapping, theoretical traditions articulate the rule of law and its relation to politics in diverse ways. With respect to the Arab world, shari’a has deep jurisprudential and normative traditions, and animates Islam’s core assumption that politics and leadership are meant to serve the rule of law, given the latter’s divine origins and purpose. Integrating this and contemporary Western theory on the rule of law is challenging, and yet conjunctions of primarily Western-based transnational legal expectations and the enduring influence of Islamic ones remain a rhetorical, and likely real, aspect of the politics of the rule of law in a country like Qatar.

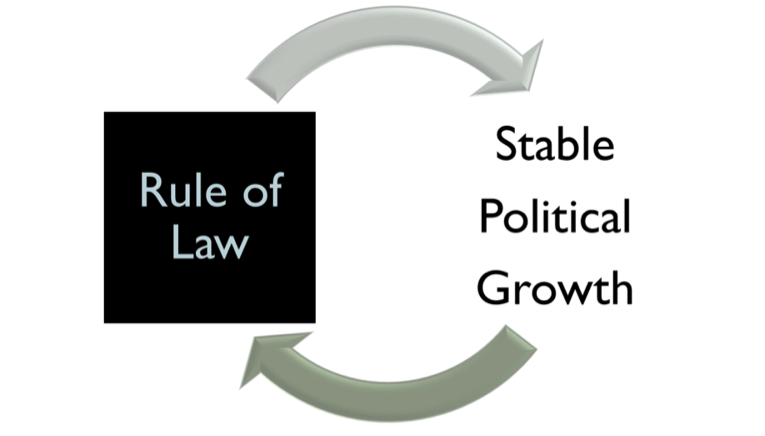

Figure 1 below summarizes the broad dynamic that informs many assumptions among rule-of-law activists and advocates around the need to bolster the rule of law. The rule of law matters globally in large part because it connects to the prospects for stabilizing growth. Indeed, in a context like Qatar, the rule of law’s stabilizing potential is especially important because of the speed of growth and the influx of population diversity it has entailed. Yet meanings of the rule of law can be diverse, contentious or unspecified. Thus, Figure 1 depicts the concept as a black box, requiring further elaboration of its meanings, especially as we look at an important, understudied case like Qatar, rather than the peculiar Western contexts in which the contemporary concept has received its most detailed analyses in academic and public policy literatures.

Figure 1: Simple Depiction Of

The Rule of Law and Stable Political Growth

This diagram is important because it underscores the need for considering the content of rule-of-law meanings prior to postulating theories about how the rule of law can be amplified. Given that the rule of law can encompass, among other things, tight law enforcement, broad individual rights against the state, and predictability around contracts and other business arrangements, content specification must be important, and forms a central role in the study of the rule of law in Qatar and Kuwait which I directed. Nonetheless, the nature, impact and reform of institutions related to the rule of law is a crucial piece of understanding links between legal ideals and political or legal outcomes.

Rule of law institutions

Indeed, perhaps because of the contentious, shifting nature of ideals associated with the rule of law, most work on the rule of law, particularly advocacy work, focuses on institutions and institutional reform. Institutions relevant to the rule of law run a wide gamut, including the police, the judiciary, lawyers, legislatures, private and public entities related to regulating economic entities and transactions, human rights organizations, and training academies for legal actors.

There is a significant body of work by rule-of-law government and non-government entities, even something of a rule-of-law industry, that looks at how to improve specific entities, so that they function better in terms of overall efficiency or contributions of political stability and/or democratization. Good work of this nature specifies what aspects of a definition of the rule of law, such as the UN definition, are enhanced by institutional improvement, and articulates mechanisms or logic for how the improvement might occur. For example, a recent volume looks in detail at reform in the judicial, military, police and anti-corruption sectors in several Arab countries to elicit broader, integrated arguments around the imperatives of institutional reform for the rule of law in reference to aspects of the UN definition.[4]

This work on legal institutional reform, far too voluminous to summarize briefly here, with some exceptions, such as the recent volume just mentioned, risks a false sense of holistic integration. The World Bank, for example, produces each year, as part of a set of global governance indicators, a figure of every country’s comparative adherence to the rule of law that lumps together a variety of measures of very diverse legal institutions. If the rule of law consists of a set of interlocking ideals, that are not necessarily contested, originating in different sources or traditions, or in conflict, then it is easy enough to assume that legal institutions form part of a uniform scaffold, so that the rule of law can be built from a common template.

Yet this basic sense of the rule of law as a set of good things that go well together, belies tensions across ideals or the difficulty, even inappropriateness, of translating legal institutions from one place to another. For example, courts that aspire confidence for both citizens and transnational entities in hyperglobalized countries permeated by diverse large business entities like Qatar and the UAE are critically important as these countries become more central to the world economy. Yet, courts or judicial review similar to what exists in both common and civil law countries have not entirely taken hold, and assumptions that they will develop along the paths that happened in these countries are indeed assumptions.

In partial response to the importance of judicial entities that are perceived as reliable specifically in relation to diverse local and global economic entities, Dubai created a parallel court system to the national courts under the auspices of the Dubai International Financial Center. This system has proven effective in resolving disputes in a manner that has given confidence to non-local business and other entities. Yet efforts to adapt this local Gulf Arab solution from the UAE to the very similar case of Qatar, in the form of the Qatar International Court and Dispute Resolution Center (QICDRC), have not proven so successful, due to a sense I observed that QICDRC’s initial British-based leadership appeared cut off from Qatari legal elites, and perhaps the greater centralization of the regular Qatari court system in Qatar’s non-federal, smaller system. This simple example highlights both broad global and specific regional challenges of trying to enhance the rule of law through the application or translation of a legal institutional model, even one that has enjoyed efficacy in other contexts.

Exactly for this reason, work on the rule of law benefits from careful linkages between plural legal ideals and sources, and diverse institutional contexts and reform strategies. Rule-of-law reform advocates have generally become more nuanced in recent years in thinking through local variations and advocacy needs in their work. Not coincidentally, the past several decades have seen the growth of legal activist organizations grounded less in Western societies, and more in other regions or non-Western countries, certainly including the Arab world. While all of this variegated institutional work on the rule of law is crucial towards reflecting the concept’s complexity, social scientific analysis also needs to take full account of the wide range of institutions and norms too readily subsumed under a broad, fuzzy conceptualization of the rule of law. By looking in detail at the diverse nature and sources of the rule of law and their relation to specific institutions, even when these do not fit together consistently, the work of my colleagues and I on the rule of law project in Qatar and Kuwait attempts to address this lacuna in a significant, if still relatively understudied, context of rapid contemporary legal growth.

David Mednicoff is a Professor of Public Policy at the University of Massachusetts ÔÇô Amherst. He is also Chair of the iPlatform Committee of Academic Fellows as well as iPlatform Director and Senior Academic Fellow. Mednicoff is a scholar of the rule of law, politics and public policy in the Middle East and elsewhere. He has received various teaching honors including a university-wide Lilly Teaching Fellowship and a US national prize for innovative teaching related to the US after 9/11. He was a Fulbright Senior Scholar in law in Qatar in 2006-2007 and a Research Fellow in 2010-2011 in the Dubai Initiative at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. He was awarded a BA from Princeton University and an MA, JD and PhD from Harvard University.

[1]  See https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/what-is-the-rule-of-law/, downloaded on July 7, 2016.

[2] See NUS MEI Insights 149 and 155 for elaboration of this point.

[3] See, for example, Joanna E. Springer and Lubna Sharab, Qataris Concerned about the Influence of International Law, Middle East Insight No. 155. Singapore: National University of Singapore, 2016.

[4]  See Eva Bellin and Heidi E Lane, eds., Building the Rule of Law in the Arab World: Tunisia, Egypt and Beyond. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2016.