What’s Keeping GCC States from Unlocking Their Innovation Potential?

- -

By Aisha Al-Sarihi

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – have made the transformation to a knowledge-based economy a critical component of their economic development visions. These moves are aimed at enabling knowledge and innovation to play a key role in economic growth, wealth creation, employment, and enhancing the competitiveness of the GCC economies beyond oil. The GCC governments have embarked on many initiatives, policies, and programmes to drive domestic innovations and promote the engagement of research entities, government, and industries in innovation activities.

The mounting economic pressures due to the collapse of oil prices since mid-2014, which have been exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic, have forced some GCC member states to embark on new initiatives to revisit their innovation gaps as means to support economic diversification and to weather the uncertainty over oil prices in future. Oman, for example, amended the name of the Ministry of Higher Education to The Ministry of Higher Education, Scientific Research and Innovation, a move aimed at placing the country among the top 20 nations in the Global Innovation Index (GII) by 2040. Just last month (June 2021), Saudi Arabia’s government formed a new Research, Development and Innovation Authority, with a specific mandate to support innovations at the national level.

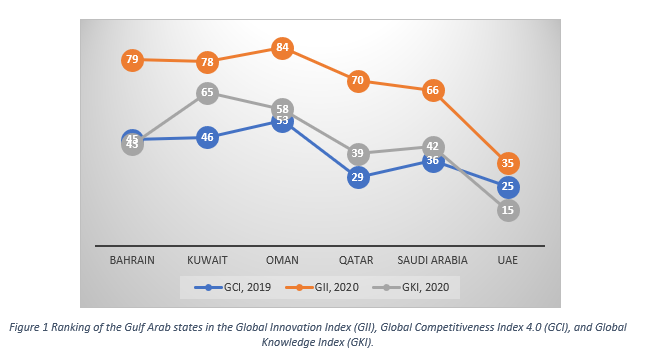

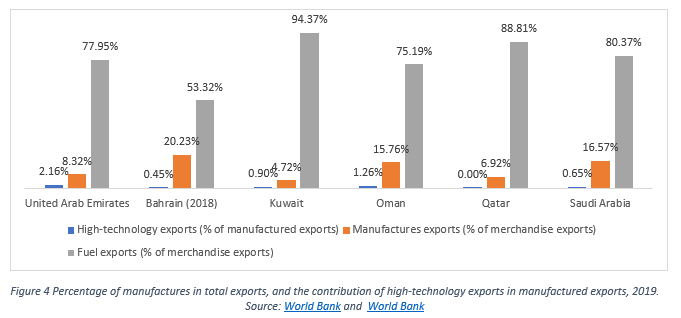

It remains to be seen whether these new initiatives will bear fruit. Earlier efforts do not provide much grounds for optimism: The 2020 edition of the GII (Figure 1) ranked all the GCC states except the UAE (34th) in the bottom half of the listing of 131 countries. Switzerland was ranked first, while Singapore placed eighth. Worse, all the GCC countries fared worse than they did in previous years. A look at the GCC’s export profile also reveals that it remains almost exclusively dominated by oil and gas.

But what has been holding the GCC back from unlocking their innovation sectors, and how can they overcome the challenges?

Who creates knowledge in the GCC?

To understand what is holding the GCC back from unlocking innovation and how it can overcome this, it is important to distinguish between invention, which refers to the creation of knowledge; and innovation, which refers to the use of knowledge and its diffusion (in a form of product or service) to the market.

The creation of knowledge and invention in the GCC normally takes place in the universities, research institutions and corporates’ R&D divisions. The hydrocarbon sector, in particular, has relatively sophisticated in-house R&D divisions compared to that elsewhere, or in universities. The in-house R&D departments of hydrocarbon companies – Aramco’s technology and innovation unit and SABIC Corporate Technology and Innovation, for example – are sophisticated and succeed because they have some form of joint-venture arrangements with foreign partners and work under their guidance to transfer and assimilate technology.

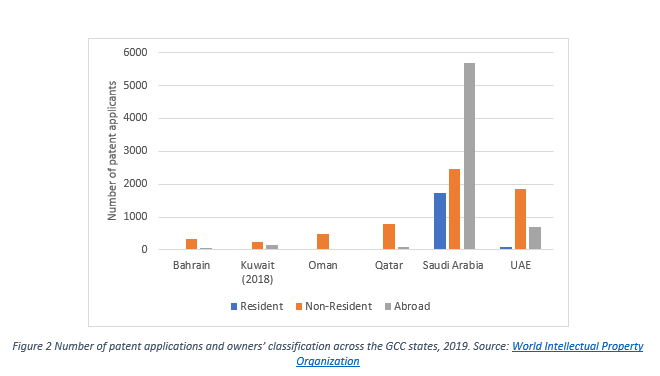

The relatively limited creation of knowledge in the GCC is due to the small number of researchers involved. The number of researchers per million inhabitants in the GCC was well below the world average of 1,411 as of 2015: 396 (2014) in Bahrain, 514 (2018) in Kuwait, 281 (2018) in Oman, and 577 (2018) in Qatar. Furthermore, most such activities in the GCC are undertaken by foreigners. Most GCC patent applications belong to foreign researchers (Figure 2). While foreign labour is a major source of knowledge transfers, the heavy reliance on them means local accumulation of knowledge is limited, especially once expatriates leave the country.

The low engagement of local researchers in knowledge and innovation activities in the GCC can be attributed to several factors, including poor education systems. These are limited when it comes to equipping students with the essential skills important for innovation, especially critical and innovative thinking skills, and entrepreneurship ability, whether at the primary, tertiary or university level. Employment choice is another factor: Most GCC citizens prefer to join the public sector, which pays well and has shorter working hours compared to the private sector. The inability of the public sector to promote productivity also creates little or no incentives for the local workforce to innovate.

Do the GCC states have national innovation systems that can integrate knowledge into the economy?

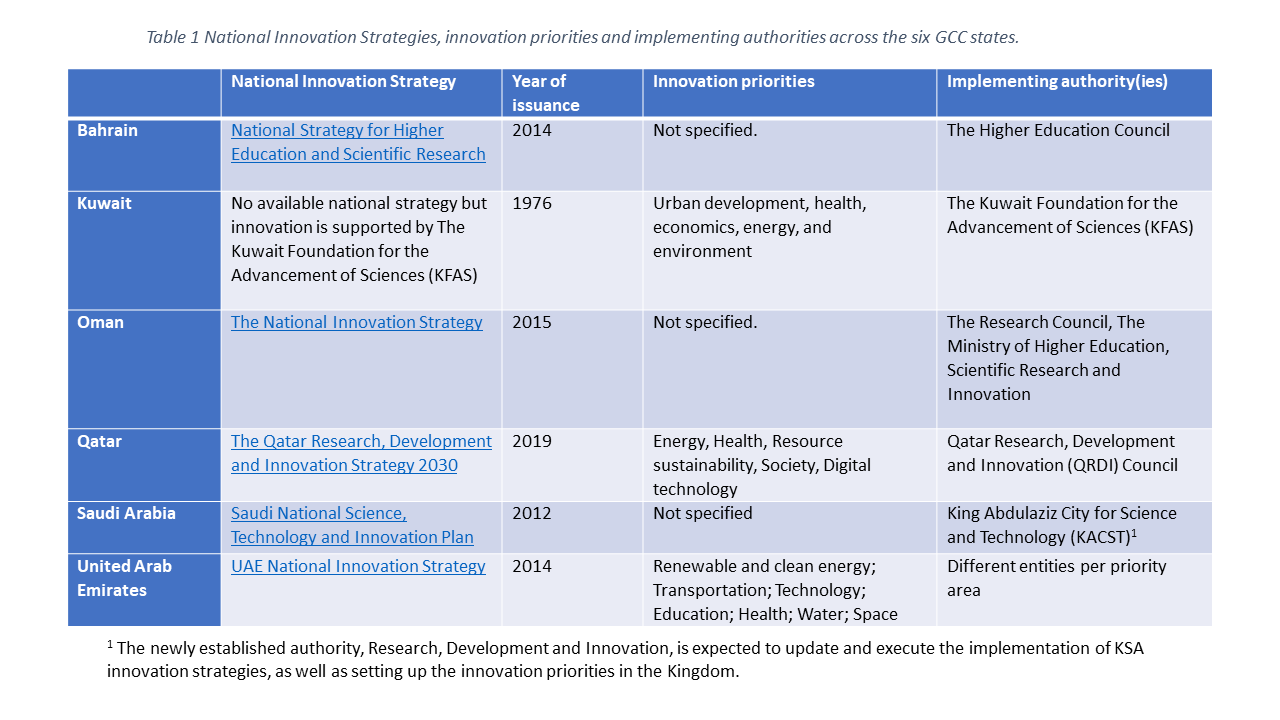

GCC governments have embarked on many initiatives, policies, and programmes in a bid to spur domestic innovation. In 1992, the grouping established a patent office in Riyadh and approved the GCC patent law in 1999 as a first step towards enabling regional innovation and integration of knowledge into economic growth. The patent office started receiving applications in 1998. But by mid-2021, the total amount of granted patents was just 11,502: 5,373 in chemistry and chemical engineering, 1,312 in pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, 2,207 in petroleum and natural gas engineering, and 2,610 in mechanical and electrical engineering. Since then, several other steps have been taken to boost innovation. GCC governments have established National Innovation Strategies in areas such as energy, water, agriculture, digital economy, health, and education (Table 1) over the past decade. While Kuwait does not have such a strategy, it established the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences (KFAS), with a focus on advancing and integrating science, technology, and innovation, in 1976.

The GCC governments have also established intermediaries that can facilitate the transfer of knowledge into their markets, including through science parks and special economic zones. Examples include Dubai Internet City, Dubai Technology Park and Dubai Silicon Oasis, and Khalifa University for Science, Technology and Research and the Masdar Institute in collaboration with MIT in Abu Dhabi; King Abdullah City for Science and Technology (KACST) and Research and Technology Park at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST); Oman’s Knowledge Oasis Muscat (KOM), and Qatar Education City and Qatar Science and Technology Park. Special economic zones across the GCC provide an innovation-ready environment and simplify set-up procedures for businesses as a strategy to promote the growth of industry clusters for international companies and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Despite these initiatives, their performance is lacking. The programmes face many obstacles, including fragmented governance structures responsible for supporting national innovation. This lack of leadership has in many cases encouraged innovation “silos” within academia and industry, creating overlap and duplication of efforts. Strengthening existing national innovation systems requires clear task assignment and responsibility among different stakeholders involved in the innovation process, including from the government, industry, and academia. The GCC governments need to put in place dedicated structures and entities that maintain regular collaboration and networks between the stakeholders involved. Regular collaboration is important to facilitate the mobilisation of resources between public and private sectors and narrow the gap for bringing innovations to market. Also, while all the GCC states have national patent laws, the lack of enforcement forces researchers to seek international protection of their intellectual property. Additionally, state bureaucracies and approval delays turn innovators off, spurring them to move to other environments that are less bureaucratic, more open, and provide better incentives.

The Way Forward to Knowledge-based economies

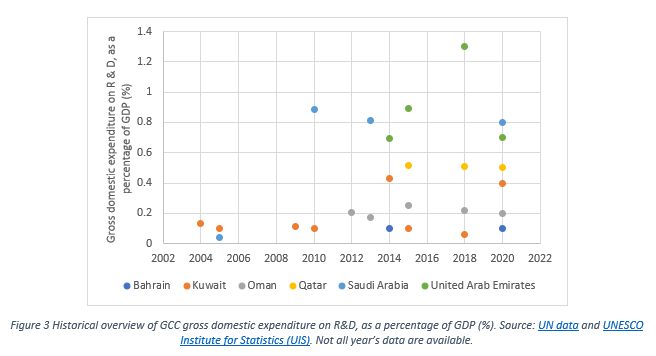

Transformation to a knowledge-based economy has been at the core of the GCC’s economic diversification programmes. For instance, under its seventh theme, “Contribution in Enabling the Private Sector’, Saudi Arabia‘s National Transformation Program (the operational element of Vision 2030) included a target to “promote the culture of entrepreneurship and innovation and transform innovations into emerging enterprises and developing human and technical capabilities”. The UAE Vision 2021 (and the current UAE Centennial 2071) included a specific theme on knowledge, “United in Knowledge”, and set a target to achieve a “competitive economy driven by knowledge and innovative Emiratis”. Oman’s 2040 Vision also sets a target to enhance its economic competitiveness by enabling a productive, diversified, and innovation-based economy. The Gulf states have made progress in developing the main ingredients necessary to build national innovation systems, including strategies, funding, and bridging R&D activities with industry. However, the contribution of innovation output (in the form of technology or services) remains relatively negligible. High technology exports, for example, account for less than 3 per cent of the GCC’s manufactured exports (Figure 4).

To unlock national innovation potential, the GCC governments will need to address the structural challenges facing the creation as well as diffusion of knowledge (in the form of products or services) to the market. This includes reforming education systems across all levels. Such changes will require a long lead time, so some measure of immediate action – providing industrial training to the local workforce, for instance – will help to bridge the gap.

The government will also need to take the lead and form agencies that will help bypass bureaucratic tangles; ensure bridging research and development activities with business and industries; and create platforms that sustain coordination and networks between different stakeholders involved in innovation.

Furthermore, the development of GCC national innovation systems should not be treated as separate from national development policies. Importantly, in achieving the drive to diversify away from oil, the GCC should ensure that top-down governance of innovation activities does not occur at the expense of bottom-up innovations, and spans beyond the focus on hydrocarbon sector.

The GCC states are at different stages of enabling national innovation systems. Yet, without swiftly addressing the aforementioned structural challenges, the programmes – with the exception of that of the UAE – are clearly not on track to be successful within their stipulated timeframes of between 10 and 20 years. While fuel still dominates Emirati exports, the UAE is a role model for other Gulf states in creating the necessary environment for innovators to thrive. It took the UAE 50 years to increase the non-oil sector’s contribution to GDP to 60 per cent. This resulted from relentless re-investment of its wealth into non-oil businesses, including construction, financial services, aviation, tourism, logistics, trading, manufacturing, and media; its support for infocomm and digital economy infrastructure; and enabling a business-friendly environment with easy access to capital and international markets.

The GCC states should realise that transition to a knowledge-based economy is a process that can span decades. Even if oil continues to be in demand for decades to come, the wealth generated from it – especially if high prices result – should not distract governments from pursuing their goal.

About the Author

Aisha Al-Sarihi is a Non-resident Fellow at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington. Her research interests include the political economy of energy transitions and sustainability, climate policy and governance, with a focus on the Arab region. She obtained her PhD at Imperial College’s Centre for Environmental Policy.

Image caption: An oil refinery at dusk. Photo: Piqsels