Our Research Associate Muneerah Razak discusses the importance of satire in the Arab world and its role in public discourse of politics against oppressive regimes in the region.

Our Research Associate Muneerah Razak discusses the importance of satire in the Arab world and its role in public discourse of politics against oppressive regimes in the region.

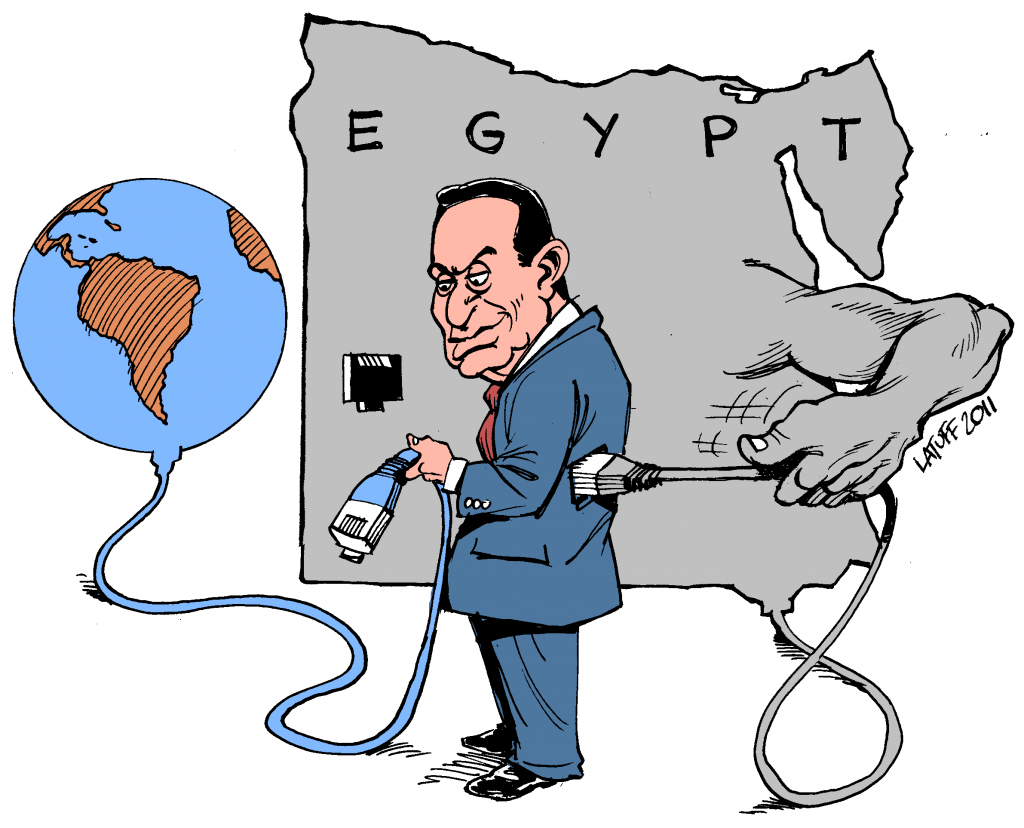

In a region where many are often marginalised from political processes, the popularity of political satires, cartoons and the prevalence of jokes in the Middle East is testament to how effective satire is in allowing people to show that they do not accept the hegemonic version of reality uncritically.

Karl Sharro, a London-based Lebanese satirist is probably one of the best known internationally. He often pokes fun at how his mysterious, orientalised native land is represented in Western media and punditry. From the Arab Spring to ISIS, Sharro uses tweets, blog posts, memes and badly-drawn cartoons to tackle delicate and complex topics. In one of his blog posts, he re-created a session between Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and his psychiatrist where the caliph is stumped about what to do after having declared the caliphate. He also turns orientalism on its head, offering occidentalist works – and returning the favour to the West in simplifying complex political events by drawing, for example, colonial maps of post-Brexit United Kingdom with a ruler.

Satire has always existed in Syria though indirect and hidden. But Syria’s civil war has seen the unleashing of a previously unthinkable black humour. “Top Goon: Diaries of a Little Dictator” is one of the several new online shows created by 10 young professional artists in Syria. Bashar Al Assad – nicknamed Beeshu in the series — is depicted as a finger puppet, along with officers in his inner circle. In one episode, Assad consults with two devils about how to deal with the uprising. They suggest he kill a single protester to scare the others. To the horror of the devils, he proclaims he will kill 30 protesters a day, torture children and shell cities. As they flee, the devils shriek, “You are completely insane! I want to get the hell out of here.”

On the surface, the satire is funny. But it is also sued to counter the regime’s insistence that all opposition is terrorist. A simple, silly puppet show pushes us to see Bashar in another light – not as the protector of stability in Syria but as a merciless tyrant. It elicits laughter for those suffering from the crackdown and at the same time, offers a counter narrative. The sacredness of the leader that was imbued since the rule of Hafez al-Assad is broken.

In Egypt, its most-watched contemporary satirist, Bassem Youssef (also named “Egypt’s Jon Stewart”) can no longer safely work. Between 2011 to 2013, Youssef’s political satire show took aim at politicians from across the spectrum. Under Morsi, the first post-revolution president, he was detained and questioned for insulting the president and Islam in general. Yet his show survived. Not so under the current president, Al-Sisi. Youssef now lives in the US.

YouTube and Facebook have become the medium of choice for satirists seeking to get past the red tape. In a BBC interview, Andeel, a young Egyptian cartoonist, said that satire was a “mirror” of reality, making an ugly reality palatable for all audiences. “Playing this character allowed me to explore certain feelings and exhale a certain amount of anger that I must have accumulated. It came to a certain point where if I kept that anger inside me, I might go crazy. So it’s better to have that craziness on the screen.”

Why does satire remain so popular? Satire offers alternative visions of politics and it is a coping mechanism for those living with difficult situations.

Yet satire has its limits. Nonetheless, I would argue that these contestations of power are still important because they are forms of everyday resistance. Despite the power of regimes and discourses, it is an indicator that people are not unthinkingly accepting reality, inevitably reclaiming some sort of power for themselves.