A Note from the Editorial Team

One big question over the dynamics roiling the GCC is what stance will be adopted by China, which is invested in the region as a result of its Belt and Road Initiative but has so far remained silent. Mohammed Turki Al Sudairi argues that this situation will continue, and that China will likely keep to its neutral stance. Among the reasons: Beijing’s view that the crisis is temporary, and its belief that the solution lies with the US and the regional players.

By Mohammed Turki Al Sudairi

Introduction

This paper attempts to understand Chinese official reactions to what is varyingly referred to in Chinese language sources as the “Gulf diplomatic-severance crisis” or the “Qatar diplomatic-severance crisis”. It accomplishes this not only by examining available official pronouncements and declarations on the issue, as well as the broader structural context shaping China’s engagement with the Gulf, but also through a careful reading of various Chinese-language academic sources analysing the crisis. Such a survey could offer insights into the rationales underlying Chinese official thinking and whether there are any factors or scenarios that might contribute to a change in its current stance. The paper is divided into three sections. The first is a general overview of the crisis narrated in conjunction with a timeline of Chinese official-level responses to it. The second is a survey of academic sources, mostly obtained through the China National Knowledge Infrastructure database, prioritising those produced by researchers and commentators on Middle East affiliated to prominent institutions and organs of the Chinese Party-state. The survey is organised around three thematic clusters: Chinese perspectives on the cases behind the crisis, its potential trajectories and long-term consequences, and finally, the prospects of its resolution. These are interspersed with references to the structural context and political-economy of Sino-Qatari relations. The concluding section attempts to tie all of these threads together in order to elucidate upon the rationales and calculations guiding China’s current behaviour regarding the crisis and whether this is susceptible to change.

Executive Summary

Two weeks following President Donald J. Trump’s attendance at the “Arab Islamic American Summit” in Riyadh in May 2017, Saudi Arabia and a group of Arab and African countries moved swiftly on June 5, 2017 to cut off diplomatic ties with Qatar. [1] Saudi Arabia and the other members of the so-called Anti-Terror Quartet (ATQ) – Egypt, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain – undertook the move following the Emir of Qatar Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani’s alleged statements on the Qatar News Agency website on May 23, in which he expressed a range of foreign policy positions fundamentally at odds with those of both Riyadh and the UAE.[2] In his comments, the Emir allegedly called for the recognition of Iran as a “great Islamic power”, criticised the Trump administration, and called for continued support for Hamas, Hezbollah and the Muslim Brotherhood. [3] He also implicitly attacked neighbouring states such as Saudi Arabia by noting that “the real danger is the behaviour of some countries that caused terrorism by adopting an extreme version of Islam that does not represent its real forgiving truth”.[4]

Saudi Arabia has accused Doha of violating the terms of the November 2013 “Riyadh Agreement”, wherein Qatar promised to halt its interference in the domestic affairs of neighbouring Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and Arab states, whether through its sponsorship of transnational organisations such as the Muslim Brotherhood, its support and cultivation of domestic opposition in those states, or via the Al Jazeera network’s negative and critical coverage of regional governments. Essentially, the crux of the crisis is a perception by ATQ member-states that Qatar plays a destabilising and outsized role in the region that must be fundamentally altered before normal diplomatic relations can resume. Since it first erupted in June 2017, the diplomatic crisis with Qatar has stabilised – it is a stalemate with little sign of possible resolution.

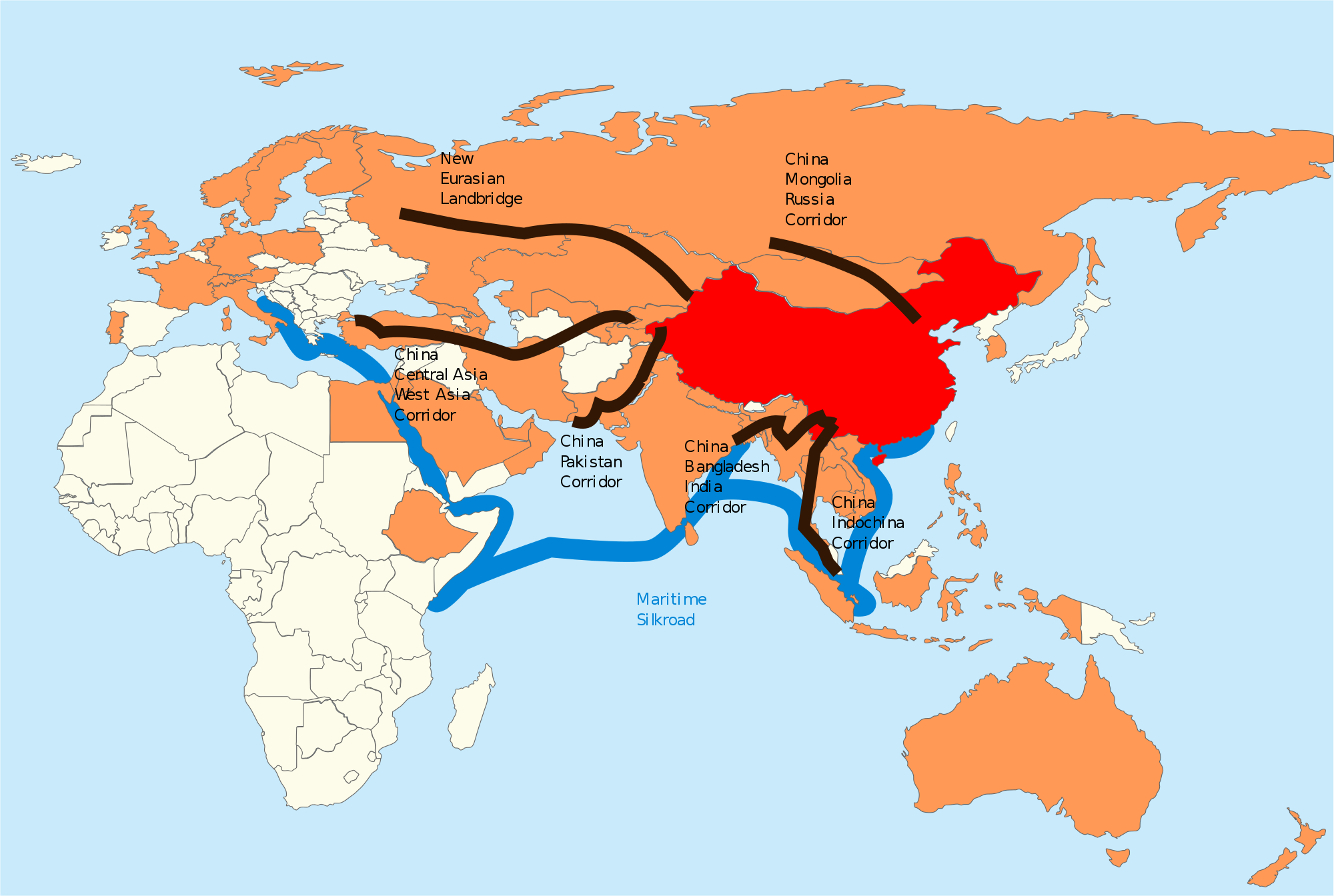

As one of the GCC’s most important trading partners and energy importers, China has adopted a neutral stance towards the disputant parties’ claims. Beijing has followed the international community’s consensus on how to best resolve the crisis, calling for negotiations between Qatar and the ATQ member-states and supporting mediation efforts aimed at ending the row. In that respect, there is a convergence between this long-standing Chinese position and that of the Trump administration. US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s statements during a tour of the region in April 2018 expressed exasperation with the continuation of the crisis and a desire for “Gulf unity”, perhaps in the hope of better re-directing regional efforts against Iran in the lead-up to Trump’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.[5]

The Chinese leadership seeks to preserve its burgeoning energy and economic ties with all the involved GCC-member states – most notably Qatar – as well as minimising the potential damage that could be inflicted upon those interests, including the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), by abjuring the adoption of a more biased or activist stance. In that respect, Beijing is adhering to its well-established patterns of engagement, as seen from its stance on other Middle Eastern rows, such as the Saudi-Iranian rivalry and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This stance is also partially a recognition of the limits of its ability to shape the outcomes of the crisis, and a well-entrenched perception that the solution (and the root cause) lies with Washington, Riyadh, Abu Dhabi and Doha, rather than with Beijing. Given existing precedent, China will likely maintain its current stance of neutrality, and none of the GCC member-states possesses the sufficient coercive or persuasive capacities to alter its approach.

This adherence to neutrality is reinforced by the optimistic reading many Chinese observers have regarding the crisis. They view it as resolvable, and that any damage it might inflict on China’s economic interests in the Gulf are temporary in nature. In a speech in Shanghai on the eve of the crisis on June 12, the former Chinese ambassador to Qatar, Gao Youzhen, opined that it was only a matter of time until a resolution came about. [6] This is based on a historically-informed reading of the conflict. For many observers, the crisis constitutes yet another episode in a long series of stand-offs that have marked Qatar’s tense relationship with its GCC neighbours since Sheikh Hamad al-Thani overthrew his father, who was close to the Saudis, in 1995.[7] From 2002 to 2008, Saudi Arabia did not have an ambassador to Doha. In March 2014, in a prelude to the current crisis, Saudi Arabia, joined by the UAE and Bahrain, withdrew their diplomats from Doha for a nine months after claiming that Qatar reneged on its promise to implement the mechanisms of oversight outlined in the “Riyadh Agreement”.[8] In that sense, the dominant perception within China is that the Qatar crisis does not pose a serious mid- or long-term challenge to China’s national interests or its BRI integration efforts with individual states across the GCC.

I. Overview of the Crisis and the Responses of Chinese Officialdom

The ATQ member-states’ decision to cut diplomatic ties with Qatar carried serious complications for Doha and its linkages with both the GCC and its wider regional surroundings. The Saudi-led military coalition against the Houthis in Yemen quickly expelled participating Qatari forces from its ranks; the Gulf ATQ member-states imposed a land-aerospace-maritime cordon around the country’s borders, accompanied by a suspension of all transnational banking transactions and exchanges with its financial institutions; and with the exception of Egypt, ATQ member-states evacuated their citizens from Qatari territory (and subsequently banned their respective populations from travelling or transiting through its territories).[9] This process accompanied a ban on Qatari-backed media and marked the start of an ongoing propaganda campaign on various outlets funded by both sides. Legislatures in the UAE and Bahrain both enacted severe cybercrime laws penalising any public displays of sympathy for Qatar, while the Saudi authorities have moved to arrest many societal figures and political activists accused of associating and expressing sympathy towards Qatar.[10] More dangerously, and reflective of possible aspirations to engineer regime-change in Doha, the Saudi-Emirati axis offered backing for the formation of an overseas Qatari opposition.[11] The intra-GCC dispute has spilled over into the halls of the Arab League, the United Nations, and even the International Court of Justice.[12] The crisis has also assumed a somewhat theatrical flair, with some Saudi sources claiming that a decision has been made to dig a canal that would physically separate the Saudi-Qatari borders from one another.[13]

Kuwait, along with Oman, although member-states of the GCC, have both refrained from cutting diplomatic ties with Qatar. Instead, Kuwait sought to play a mediating role in the dispute.[14] Other regional actors, sensing new opportunities as a result of this intra-GCC crisis, have been drawn into the fray. Iran, for instance, provided Qatar with a vital outlet through permission to use its maritime and aerospace routes, to the outside world. This enabled Doha to overcome, albeit at considerable financial cost, the consequences of the boycott imposed by its neighbours.[15] These overtures, among others, facilitated the re-normalisation of Iranian-Qatari relations, since Doha had recalled its ambassador from Tehran following the attack on the Saudi diplomatic mission there in 2016.[16] Turkey’s involvement has been even more serious with respect to its potential impact on the integrity of the GCC security structure. On June 9, 2017, the Turkish Parliament authorised Ankara to dispatch troops to act as an added deterrence – in addition to the already existing Turkish military presence in Qatar since 2014 – against any possible Saudi-Emirati military attack.[17] This effectively re-introduced a Turkish presence along the Gulf littoral nearly a century after the Ottoman withdrawal from the region.[18]

In light of these alarming and ever escalating events, the Chinese government immediately dispatched the Head of the West-Asia North Africa Section of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Deng Li, to both Qatar and the UAE on June 13-15, 2017, for an exchange of views.[19] On June 22, Foreign Minister Wang Yi articulated China’s position on the crisis during a press conference in Jordan. He stressed that whatever problems existed between Qatar and the ATQ member-states should be resolved through dialogue undertaken within the framework of the GCC. [20] He also added that Qatar, like all Arab states, firmly opposes terrorism and extremism. Wang further added that as a friend to all Arab states, China was willing to exert a constructive influence when needed. His statement constitutes the fullest and clearest articulation of Beijing’s stance on the crisis since it began.

On June 23, the ATQ member-states issued a list of “13 demands” stipulating their conditions for resolving the crisis with Qatar following Kuwaiti mediation efforts, and Doha was given 10 days to deliberate the list and respond. These demands included scaling down diplomatic ties with Iran once more, shutting down the existing Turkish military installation, ending the country’s patronage of terrorist organisations as well as its hostile international media outlets, adhering to the “Riyadh Agreement”, and paying reparations to countries affected by its state-sponsored terrorism among others.[21] Although these demands were summarily rejected by Doha on July 1, hope persisted for a negotiated settlement of the crisis. Following renewed mediation by the Kuwaitis, an updated “six principles” list was issued and again rebuffed by Qatar, which insisted that the crisis could only be resolved through direct dialogue and respect for its sovereignty as outlined in the Qatari Emir’s July 21 national speech.[22] During this phase, China received on July 18-19 two high-level delegations from the UAE (Minister of State Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber) and Qatar (Foreign Minister Mohammed Abdulrahman al-Thani) for consultations.[23]

Following the first two months, Chinese diplomatic activity with respect to the crisis subsided, perhaps due to a newfound recognition in Beijing of minimal economic and military escalation in the new round of intra-GCC infighting. A natural reversion to a “business as usual” type of status quo took place. The crisis did not threaten or hinder the continued development of Sino-Qatari bilateral relations (or, for that matter, negatively impact Sino-Saudi or Sino-Emirati ties). In fact, the crisis may have strengthened Sino-Qatari relations in new ways: The sale of the SY-400 ballistic missile system, on full display during Qatar’s national day celebrations in December 2017, marked what appeared to have been the first major Qatari purchase of Chinese sophisticated weaponry.[24] This may have been prompted by a desire to tilt the trade balance in China’s favor and to present itself – due to its decision to build a drone factory in Saudi Arabia – as a balanced partner to all parties involved.[25] Chinese trade delegations have also pushed to forcefully enter the Qatari market in 2018, although “news” of this sort should be viewed sceptically, as Qatari media’s coverage of such events often veers into propaganda by emphasising how the country “broke” the siege imposed by the ATQ member-states. [26]

II. The Chinese Academic Debate on the Qatar Crisis

The “black-box” nature of Chinese policymaking and the lack of access to government sources makes it difficult to analyse the rationales and calculations shaping official thinking towards the Qatar crisis. Nonetheless, given the links between academia and government in China, some of the official thinking can be glimpsed from a survey of the academic debate within China that focuses on various aspects of the diplomatic row, including its fundamental causes, the prospects for its future evolution, and the impact it may have on Chinese national interests.[27] The general tone of the debate suggests that the crisis is largely viewed as being beyond the control of Beijing, but is nevertheless now at a manageable level with little possibility for further dramatic swings or escalation. More importantly, the crisis is not deemed to be a threat to Chinese interests over the long run. This reading, insofar as it approximates official thinking, offers observers a means by which to understand the logic underlying the stances adopted by Chinese officials towards the Qatar crisis.

Chinese Perspectives on the Causes and Catalysts behind the Crisis

The views of Chinese Middle East specialists could be divided into three clusters with respect to what they identify as the fundamental reasons behind the eruption of the crisis.[28] The first cluster views Trump’s visit to Riyadh in May 2017 and his associated efforts to construct an Arab version of the “North Atlantic Treaty Organization” as having empowered Saudi Arabia to adopt a more aggressive foreign policy stance towards Qatar. Scholars in this camp believe that American policy changes towards the Middle East encouraged different Gulf countries to adopt separate and contradictory diplomatic stances towards Iran that ultimately contributed to the eruption of the crisis and, potentially, to the collapse of the GCC as a viable organisation. Exponents of such a view have a conspiratorial understanding of the US role and see it ultimately as a destabilising and imperialist actor working against the common interests of the Middle East.

The second cluster places the blame squarely on the UAE, which is seen as having goaded the Kingdom – by means of influence exercised by Abu Dhabi’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed on the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman – to attack Qatar in order to pre-empt Doha from becoming a genuine and competitive alternative to Dubai or Abu Dhabi. The third cluster, unlike the preceding two, acknowledges that the crisis is driven by legitimate Saudi and Arab national security concerns over Qatar’s subversive activities in the region. Other scholars have often aired views mixing these various perspectives: A leading Chinese scholar on the Middle East identifies Qatar’s funding for militant groups as a precipitating factor behind the crisis, although he also stresses the US role in facilitating its outbreak (and, potentially, in bringing about its resolution).[29] In a broader structural take on the crisis beyond these three clusters, one Chinese expert affiliated to a major government think tank sees the origins of the crisis as stemming from Qatar’s desire to escape from the shadow of its larger neighbour, Saudi Arabia, through the pursuit of an independent foreign policy.[30]

Chinese Perspectives on Crisis Trajectories and its Potential Consequences

Chinese academics generally dismiss the potential mid- and long-term impact of the crisis on international stability and global financial markets. One Chinese researcher working in an institute associated with the powerful National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) downplayed the negative global economic fallout arising from the crisis and suggested that there was little room for further escalation.[31] In terms of the crisis’ impact on China’s national interests, however, there are recognisable differences, ranging from those sensing an opportunity for Chinese economic expansion to those who worry about the potential risks it might bring.[32] For instance, some observers see opportunities for Chinese companies, enabled by the decline in energy prices and Qatar’s own need for outside investment in light of the crisis-induced capital flight, to deepen their economic footprint in the country.[33]

However, not everyone shares this optimistic appraisal. Some point to the contraction of business confronting Chinese companies in Qatar as one example of the negative fallout arising from the crisis, although little in the way of detail is offered to back up this claim.[34] The abovementioned NDRC-affiliated researcher, while unperturbed by the crisis’ potential consequences on the global economy, is more circumspect with regards to its possible impact on China’s own economic and strategic interests. He worries it could obstruct – albeit for a limited time – the establishment of a China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor under the umbrella of the BRI.[35] There is the additional concern that China will eventually be subject to various political and economic pressures that could force it to take sides in the conflict as Saudi Arabia, like Qatar, is also a strategic partner (zhanlve huoban) to China and one that has already expressed deep commitment to the BRI. Furthermore, the intra-GCC crisis will have a definitive impact in derailing the China-GCC free trade agreement talks, which were restarted in early 2016, and would undoubtedly complicate China’s efforts at internationalising the renminbi.[36]

Others have taken the argument one step further, arguing that the rift and the accrued economic damage to Chinese interests only serves to highlight the state of insecurity afflicting the Middle East region. Accordingly, there is a serious need for the Chinese leadership to carefully re-examine the country’s strategy of engagement with West Asia. An expert associated with a Ministry of Commerce think tank suggests that while the Arab region is an important trading partner to China that should not be ignored, its overall importance, when compared to other regions, is not that great.[37] The region’s economic clout is limited, accounting for only 6.7 per cent of global GDP; Sino-Arab joint-investment projects have generally failed to take off; and the Middle East’s overall abysmal conditions – brought about by the vulnerability of regional states to political crises, a lack of societal cohesion, and the prioritisation of ethnic-religious identities over that of the state – makes it a difficult and risky arena for business over the long-run. Interestingly, the same researcher makes an exception for Qatar: In his view, it constitutes an oasis of stability within the Arab world, demonstrated by its success in weathering the consequences of the economic cordon imposed by the ATQ member-states. This, they argue, should be grounds for the further development of Sino-Qatari relations.

This positive take on Sino-Qatari ties is a dominant view among Chinese experts and is partially a result of the significant advances that had been made in the relationship, albeit not one that could be described as unique in the Gulf environment. In the third decade since the establishment of mutual diplomatic recognition in July 1989, Sino-Qatari bilateral ties have entered a “Golden Age”, paralleling developments seen elsewhere in Sino-Gulf relations.[38] Much of this has been propelled by growing Chinese imports of liquified natural gas (LNG). In 2009, Qatargas concluded a 25-year agreement to supply five million metric tons (m/t) of LNG to China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) and PetroChina (PC) annually.[39] Prior to this agreement, Qatar did not export LNG to the Chinese market, but the conclusion of the deal, in conjunction with Beijing’s own growing demand for energy, enabled Qatar to emerge as one of China’s largest suppliers of LNG.[40] As a result, Qatar has succeeded in maintaining this position despite increasing competition from overland natural gas exporters in Central Asia (Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan) and LNG exporters from Australia and the US.[41] In 2016, Qatar was the source of nearly 31 per cent of all Chinese LNG imports.[42] The centrality of LNG in Sino-Qatari relations could be discerned from their bilateral trade balance: in 2017, its total value stood at $8 billion, 80% of which was counted in Qatar’s favour.[43]

In addition to this energy dynamic, Qatar has succeeded in positioning itself as a potential node for Chinese economic and financial activities within West Asia and beyond.[44] Since the mid-2000s, the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) and Qatar Holding (QH) have sought to funnel capital and procure shares within Chinese banks and companies, including Alibaba, Citic Group, the Industrial Commercial Bank of China, and the Agricultural Bank of China, among others.[45] This trend has been accelerated by the decision of the Chinese Securities Regulatory Commission and State Administration of Foreign Exchanges to grant Qatar the status of a Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor in 2012, enabling it in turn to expand its access to renminbi (RMB)-denominated assets.[46] In April 2015, Qatar established the Middle East’s first RMB clearing house, processing nearly $20 billion in its first year of operation alone.[47] It also eagerly signed up to the BRI when it was first announced in 2013, and is often depicted in Chinese official rhetoric as being one of the first GCC member-states to join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.[48] However, these approaches have had a limited impact in attracting Chinese investments to Qatar. According to the current Chinese ambassador to Qatar, Li Chen, Chinese investments in the country amounted to only $300 million as of 2016.[49] Nevertheless, Chinese construction companies have been heavily involved in various infrastructural projects within Qatar, a presence that only grew in the lead up to the 2022 World Cup games.

Paralleling developments in the economic sphere, Sino-Qatari political ties improved markedly over the past decade. Elite-level exchanges have been regular, starting with the then next generation leaders of the two nations. In 2008, Vice-President Xi Jinping made a state visit to Qatar that was reciprocated by Crown Prince Tamim at the Beijing Olympics.[50] The two heads of state undertook state visits again in 2014 and signed a declaration that upgraded the status of Sino-Qatari relations, in China’s diplomatic nomenclature, into a “strategic partnership”. This designation not only tied the economic modernisation projects of both states – Qatar’s “2030 Vision” and China’s “Two Centennials” – together, but also enhanced security and military cooperation.[51] Qatar is particularly active in engaging and supporting the institutions and forums organised by China, sending sizeable delegations to the annual Bo’ao Asia Forum (the so-called “Chinese Davos”), the 2014 Shanghai-based Summit for the Conference on Confidence Building Measures in Asia, and the 2017 BRI Summit, among others.[52] Additionally, Doha has played host to the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum (CASCF), a major ministerial-level biennial event coordinating Arab-regional cooperation with China, in 2014.

There have also been recognised synergies in Qatar and China’s diplomatic perspectives regarding how to resolve, or at the very least manage, multiple regional conflicts across Eurasia, most notably in places such as Palestine and Afghanistan. Both governments share a willingness to engage as wide of an array of actors on the ground as possible.[53] According to some observers, Beijing appreciates Doha playing a mediating role in many of those conflict-ridden regions and thus enhancing much-needed stability along different sections of the BRI-related “economic corridors” across Eurasia and the Middle East.[54] In July 2016, for example, China received a delegation from the Doha-based political office of the Taliban, suggesting that it is utilising some of the diplomatic connections cultivated by Qatar in pursuit of its own national interests.[55]

Chinese Perspectives on Crisis Resolution and Policy Recommendations

Chinese academics seem to be near a consensus on what they recommend Beijing should do in dealing with the Qatar crisis.[56] Since China enjoys solid strategic partnerships with all the parties involved in the dispute, it is well-positioned to play a potentially constructive role in mediating or supporting peace talks. However, given the challenging realities of Middle Eastern conflicts and disputes, this is qualified by an emphasis that national interests would be better served by China maintaining its stance of neutrality and abjuring any activist or idealistic foreign policy. Beijing should also recognise that while it can promote dialogue, the keys to solving this crisis lie with the involved parties as well as with Washington. Turning towards the BRI, the prevailing view among Chinese researchers is that since the initiative is predicated on the willing participation of different countries on a bilateral level, the crisis does not pose a threat to it. Many Chinese scholars advocate the continued promotion of the BRI in the Middle East and encourage Beijing to utilise the different institutional mechanisms at its disposal, such as CASCF and the China-Arab Political Strategic Dialogue, in order to intensify bilateral and multilateral economic cooperation.

III. Concluding Remarks

In examining the academic debate over the Qatar crisis, China’s official stance of neutrality could be understood as a function of multiple calculations. First, there are limited costs entailed in adopting such a position, and Beijing – as its continued economic engagement with all involved parties in the GCC demonstrates – has not incurred any serious diplomatic or political costs for assuming such a stance. By contrast, leaning towards one side or adopting a more active mediational role could bring about unwarranted risks to Chinese interests. Second, Beijing views the intra-GCC dispute as temporary in nature. Its continued promotion of normal economic relations with all GCC member-states and its continued hope for the conclusion of a China-GCC Free Trade Agreement reflects that belief. Third, China perceives that the solution to the crisis lies principally with the US and local regional powers. This is partially a result of its longstanding view that the Gulf lies within the American zone of hegemony and control, and that all problems therein are a result of Washington’s involvement.

Looking ahead towards the future, one key issue to consider is whether China could be convinced or pressured into abandoning its current stance in favour of supporting one side over the other. During his July 2017 visit to China, the Qatari Foreign Minister organised a workshop with the late head of Al Jazeera, Izzat al-Shahrour, in a bid to explain to Chinese intellectuals Doha’s stance on the disagreements with ATQ member-states.[57] The Emiratis, likewise, have sought to persuade China to support the ATQ’s stance, highlighting the far greater importance and size of China’s ties to Saudi Arabia and the UAE in comparison to its relations with Qatar. In addition, UAE sources repeatedly present Qatar as having played a de-stabilising role with respect to Chinese national security and stability, particularly through Al Jazeera broadcasts and Qatar’s support of non-state actors in Syria and Iraq, under whose banners many Uighurs from Xinjiang have fought.[58]

It is unlikely that China will depart from its position of neutrality in the foreseeable future. First, notwithstanding the few sporadic attempts noted above, the lobbying energy of the disputant Gulf parties has focused on the US itself as the main actor for resolving the crisis. This gives credence to the common Chinese view that the solution to this diplomatic row cannot be found in Beijing – a view that is probably shared and accepted by decision-makers involved in this intra-GCC dispute. Second, none of the GCC member-states has the sufficient coercive or persuasive capacities to alter Chinese behaviour in any meaningful form. This is not only a result of the existing power asymmetry between China and the Gulf (and the mutual economic dependency that locks the two regions together), but also because other major powers – the US, the European Union, and India, among others – have not been obliged to make a “choice” between the contending parties either. It would be difficult, therefore, for the ATQ member-states to hold China to account for its weapons sales to Qatar, for example: Since June 2017, Doha has made several major purchases from the US, Britain, France and Italy, to name just a few.[59]

Third, it is also unlikely that any of the disputant parties are willing to risk damaging their bilateral ties with China in exchange for an unguaranteed change in Beijing’s stance. Saudi Arabia, the head of the ATQ, only recently oversaw a positive reset in Sino-Saudi relations following years of disagreement over regional issues such as Syria. It is improbable that Riyadh, or any of the other GCC capitals, will repeat such mistakes. Fourth, it is difficult to exploit Chinese sensitivities over foreign interference and terrorism as a means of alienating it from one party over the other. With respect to the Al Jazeera frame, there have been repeated issues with Al Jazeera English centering on its coverage of the Chinese prison-labour system and the Wukan uprising in Guangdong, but this has not appeared as a major point of contention within Sino-Qatari relations.[60] It is possible, however, that Al Jazeera’s decision to launch a Mandarin-language website might be a cause of concern in the future.[61]

The terrorism sponsorship designation applied by ATQ member-states on Qatar, moreover, is highly problematic and unpersuasive to Chinese officials. The GCC states are all seen as having been involved in supporting transnational terrorist organisations over the past few decades, with few exceptions. With respect to China’s own internal domestic security situation, Saudi Arabia is viewed by both Chinese academics and officials as exerting a far more negative and destabilising influence on the country’s Muslim ethnic minorities than Qatar, and is seen as one of the principal “black hands” (hei shou) offering ideological and material succour for domestic terrorism. Also, since 2015, China and Qatar have moved to strengthen bilateral counter-terrorism cooperation, and Qatar has been swift to denounce terrorist attacks in the Chinese mainland – a fact very much appreciated by the Chinese authorities.[62]

China seeks to present itself as a constructive non-hegemonic actor with good ties to all sides. Though a long shot, this stance of neutrality, and its immunity from intra-GCC lobbying, offers room – if one were to examine this from Washington’s angle – for a creative US administration to organise a Sino-American coordinated effort to pressure both sides to resolve their differences. This current moment of rising Sino-American tensions over trade and the ongoing South China Sea disputes, as well as internal (and international) fatigue within the Gulf over the crisis among some actors, constitutes an opportune moment to close this chapter and contribute positively to easing tensions (somewhat) between Washington and Beijing. It is likely that such coordination, if linked with other strategic issues of contention, might be welcomed in China as a trust-building initiative and enable both sides to appear as stability-oriented actors at a time of growing uncertainty within the international system. But the Trump administration’s own (lack of) clarity and strategic vision with respect to the resolution of the GCC crisis complicates matters and dims prospects for such a move. Given the recent American diplomatic debacles in the Korean peninsula and with Iran, however, the willingness and capacity of the Trump administration to handle the nuances of this intra-GCC dispute are open to question, especially since their overtures might be read as “theatrical performances” rather than substantive efforts to resolve the crisis.

[1] The Anti-Terror Quartet, also called the Arab Quartet, refers to the core coalition of Arab states – Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Egypt – who have shared concerns regarding Qatar’s regional role and whom have coordinated their diplomatic efforts to punish and pressure Doha into yielding to their demands. The ATQ member-states are joined by a few allied or supporting states including Yemen, Mauritania, Comoros, Maldives, and Libya, all of whom have also severed their diplomatic ties with Qatar. Jordan and Djibouti, which are part of this broader coalition, opted to only downsize the level of their diplomatic representation to Qatar.

[2] The Qatari position has been one that these websites were hacked and the statements planted by hostile forces, with the UAE being accused as the guilty party. The Emirati Foreign Minister Anwar Qarqash has since denied these claims: “Who Hacked Qatar’s News Sites?” The Atlantic, July 17, 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/news/archive/2017/07/uae-denies-qatar-hack-charges/533826/

[3] “Qatari Emir: Doha has ‘tensions’ with the Donald Trump administration.” Alarabiya (The Arabian), May 24, 2017. https://english.alarabiya.net/en/News/gulf/2017/05/24/Qatar-says-Iran-an-Islamic-power-its-ties-with-Israel-good-.html

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Pompeo Rails Against Iran During Middle East Tour.” The Washington Post, April 30, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/pompeo-rails-against-iran-during-visit-to-saudi-arabia-1524998232

[6] “Gao Youzhen: Jiejue Kataer Duanjiao Weiji, Zhishi Shijian Wenti” (“Gao Youzhen: Solving the Qatar Diplomatic Severance Crisis is only an Issue of Time”), Guanchazhe (Observer), June 12, 2017. www.guancha.cn/gaoyouzhen/2017_06_12_412811_1.shtml.

[7] Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, Qatar and the Arab Spring, (Oxford University Press, 2014), 29-30.

[8] Ibid., 181.; “nas bayan sahb al-sufara al-khalijiyeen min Qatar.” (“Statement on the withdrawal of Gulf Ambassadors from Qatar”). Gulf Centre for Development Policies (undated). https://www.gulfpolicies.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1670:2014-03-08-08-10-42&catid=158:2012-01-03-19-52-52&Itemid=266

[9] Qataris were likewise ordered to leave the territories of the boycotting GCC member-states, a situation that has led to a momentary separation of many mixed Qatari-GCC families and led to a humanitarian outcry that has since been addressed by the boycotting states: “al-imarat wal su’udiyya wal bahrayn: tawjeehat limura’at al-awda’ al-insaniyya lil usar al-mushtaraka ma’ Qatar.” (“Emirates, Saudi and Bahrain: orders to re-examine the humanitarian situation of joint families with Qatar”), CNN, June 11, 2017. https://arabic.cnn.com/middle-east/2017/06/11/qatar-saudi-uae-bahrain-families.

[10] “al-naib al-‘am: ata’atuf ma’ Qatar ‘ubra mawaqi’ al-tawasul jarimah yu’aqib ‘alayha al-qanun,” (“The General Prosecutor: Showing Sympathy to Qatar on Social Media Sites is a Crime Punishable by Law”), Emarat Alyoum (Emirates Today), June 7, 2017. https://www.emaratalyoum.com/local-section/other/2017-06-07-1.1001843; “al-bahrayn: al-ta’atuf ma’ hukumat Qatar jarima ‘uqubatuha al-sajn 5 sanawat.” (“Bahrain: Sympathizing with the Government of Qatar is a Crime Entailing 5 Years of Prison”), Albayan (The Declaration), June 8, 2017. https://www.albayan.ae/one-world/arabs/2017-06-08-1.2971457; “Masdar Su’udi: i’tiqal Salman al-‘Awdah kashaf ‘illaqatah bi Qatar.” (“A Saudi source: The arrest of Salman al-‘Awdah revealed his ties to Qatar”), Erem News, 17 September 2017. https://www.eremnews.com/news/arab-world/saudi-arabia/993298

[11] “UAE says Qatari royal leaves after claim he was being detained.” Reuters, January 15, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-gulf-qatar-emirates/uae-says-qatari-royal-leaves-after-claim-he-was-being-detained-idUSKBN1F30X0

[12] “Qatar takes UAE to World Court.” The Gulf Times, June 11, 2018. http://www.gulf-times.com/story/595939/Qatar-takes-UAE-to-World-Court

[13] “taqareer ‘an ‘qanat maiyya’ tafsil Qatar bariyan ‘an al-su’udiyya.” (“Report on the a Water Canal that will Separate Qatar overland from Saudi”), CNN, April 7, 2018. https://arabic.cnn.com/middle-east/2018/04/07/water-canal-saudi-qatar-reports.

[14] “amir al-Kuwait yas’a lihiwar mubashir li hall al-azma al-khalijiyya.” (“The Emir of Kuwait is Seeking Direct Negotiations to Solve the Gulf Crisis”), Alsharq alaawsat (The Middle East), August 15, 2017. https://aawsat.com/home/article/995351/%D8%A3%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%83%D9%88%D9%8A%D8%AA-%D9%8A%D8%B3%D8%B9%D9%89-%D9%84%D8%AD%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%B1-%D9%85%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%B4%D8%B1-%D9%84%D8%AD%D9%84-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%B2%D9%85%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AE%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%AC%D9%8A%D8%A9

[15] “Qatari flights to use Iran’s airspace.” Mehr News Agency, June 6, 2017: http://en.mehrnews.com/news/125759/Qatari-flights-to-use-Iran-s-airspace

[16] “Qatar restores diplomatic relations with Iran, countering Arab demands.” The Christian Science Monitor, August 27, 2017. https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Middle-East/2017/0824/Qatar-restores-diplomatic-relations-with-Iran-countering-Arab-demands

[17] “al-barlaman al-Turki yuwafiq ‘ala nashir quwat fi Qatar.” (“The Turkish Parliament Authorizes the Deployment of Forces in Qatar”), CNN, June 7, 2017: https://arabic.cnn.com/middle-east/2017/06/07/turkey-parliament-troops-qatar

[18] The presence of the American military base in al-‘udeid, which hosts the headquarters of the US Central Command, is probably of more significant factor in shaping the calculations of the ATQ member-states in undertaking any possible military operations against Qatar. This may partially explain the lobbying efforts carried out by Emirati officials in Washington aimed at engineering a move of the base from Doha to Abu Dhabi. “U.A.E. Ambassador: U.S. Should Rethink Its Air Base in Qatar.” Bloomberg, 14 June, 2017. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-06-13/emirati-ambassador-us-should-rethink-its-air-base-in-qatar

[19] “waijiaobu yafeisi sizhang Deng Li fangwen alianqiu.” (“Ministry of Foreign Affairs Asia-Africa Section, Section Head Deng Li Visits United Arab Emirates”), Zhongguo renmin gongheguo waijiaobu wangzhan (The People’s Republic of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affair’s website), 13 June 2017. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/wjbxw_673019/t1469917.shtml.; “waijiaobu yafeisi sizhang Deng Li fangwen kataer.” (“Ministry of Foreign Affairs Asia-Africa Section, Section Head Deng Li Visits Qatar”), Zhongguo renmin gongheguo waijiaobu wangzhan (The People’s Republic of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affair’s website), June 15, 2017.www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/gjhdq_676201/gj_676203/yz_676205/1206_676596/xgxw_676602/t1470299.shtml.

[20] “Wang Yi tan dangqian haiwan weiji.” (“Wang Yi Disucsses Current Gulf Crisis”), Zhongguo renmin gongheguo waijiaobu wangzhan (The People’s Republic of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affair’s website), June 22, 2017. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/wjbz_673089/zyhd_673091/t1472508.shtml

[21] A recent talking point for pro-ATQ advocates on this issue has been to emphasize Qatari transfers and of money to non-state actors operating in Iraq and aligned with Iran in order to release kidnapped Qatari royals, a deal that has also been connected to a much broader regional arrangement to shift the sectarian composition of two strategic townships in Syria. Worth, Robert F. “Kidnapped Royalty Become Pawns in Iran’s Deadly Plot.” The New York Times, March 14, 2018: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/14/magazine/how-a-ransom-for-royal-falconers-reshaped-the-middle-east.html ; “Arab states issue 13 demands to end Qatar-Gulf crisis.” Aljazeera, July 12, 2017. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/06/arab-states-issue-list-demands-qatar-crisis-170623022133024.html; Wood, Paul. “Did Qatar pay the world’s largest ransom?” BBC, July 17, 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-44660369.

[22] “awal khitab li amir Qatar yatanawal al-azma al-khalijiyya.” (“First Speech of Qatar’s Emir Dealing with the Gulf Crisis”), Aljazeera, 21 July 2017. http://www.aljazeera.net/encyclopedia/events/2017/7/21/أول-خطاب-لأمير-قطر-يتناول-الأزمة-الخليجية .

[23] “Wang Yi huijian kataer waijiao dachen: zaitan haiwan weiji.” (“Wang Yi Meets with Qatar’s Foreign Minister: Discuss Gulf Crisis”), Zhongguo renmin gongheguo waijiaobu wangzhan (The People’s Republic of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affair’s website), July 20, 2017. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/gjhdq_676201/gj_676203/yz_676205/1206_676596/xgxw_676602/t1479103.shtml.

[24] Karasik, Theodore and Cafiero, Giorgio. “Why China Sold Qatar the SY-400 Ballistic Missile System.” LobeLog, December 21, 2017. lobelog.com/why-china-sold-qatar-the-sy-400-ballistic-missile-system/

[25] “zhongguo shate liangge da keji jituan hezuo zhanlingzhong wurenji shichang.” (“China and Saudi Technology Corporations Discuss Cooperation on Occupying the Drone Market”), Fenghuang junshi (Phoenix Military Affairs), May 17, 2017. http://news.ifeng.com/a/20170517/51108594_0.shtml.

[26] “Significance of Qatar-China trade relations highlighted.” The Peninsula, March 27, 2018. https://thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/27/03/2018/Significance-of-Qatar-China-trade-relations-highlighted

[27] The sources were largely drawn from a comprehensive search of the zhiwang database of all articles written on the crisis following its eruption, as well as a few dealing with Sino-Qatari relations writ-large.

[28] This division draws upon the outline created by Sun Degang, the Vice Director of the Middle East Research Center at Shanghai Languages University and the Egyptian scholar Hend Elmahly for categorizing the different Chinese views surrounding the issue. Sun Degang & Anran. “‘tongzhihua lianmeng’ yu shate – kataer jiaoe de jiegou xinggenyuan.” (“‘Homogenizing Alliance’ and the Institutional Sources of Saudi-Qatar Worsening Relations”), Xiyafeizhou (West Asia – Africa) no. 1, 2018: 72.

[29] Wang Suolao. “kataer duanjiao fengboxia de zhongdong luanju.” (“The Chaotic Situation of the Middle East under the Qatar Diplomatic Severance Crisis”), Dangjian (Party Construction), August 2017: 62-64.

[30] Yang Guang.“zai zhongdong duojihua qushizhong xunqiu duobian hezuo.” (“Searching for Multilateral Cooperation in the Middle East’s Multipolar Trend”), Guoji shiyou jingji (International Oil Economy), no. 10, vol. 25, 2017: 3.

[31] Jin Ruiting. “jingti kataer duanjiao shijian dui ‘yidaiyilu’ jianshe de fumian chongji.” (“Sounding the Alarm over the Negative Impact of the Qatar Diplomatic Severance Event on the Construction of the Belt-Road”), Zhongguo fazhan guancha (China Development Observer), no. 12, 2017: 27-29.

[32] Amusingly, a portion of the Chinese news coverage on the issue has also been ecstatic about the possibility that the crisis might lead to the cancellation of Qatar hosting the 2022 World Cup, with China emerging as the main beneficiary from such an outcome. “kataer zao’ou ‘duanjiaochao weiji’, 2022 shijiebei yishi zhongguo?” (“Qatar has Suffered a Tide of Diplomatic Severances, Could the 2022 World Cup be Moved to China?”) Huanqiu (The Global Times), June 6, 2017. http://world.huanqiu.com/exclusive/2017-06/10784819.html;“kataer fasheng ta fangshi duanjiao jiujing shi shenme yuanyin dui zhongguo you he yingxiang?” (“What are the Reasons for Qatar’s Diplomatic Severance Collapse? What Impact will it have on China?”), Zhonghuawang (China Web), June 7, 2017. http://news.china.com/news100/11038989/20170607/30665506.html; “ni yiwei kataer duanjiao fengbo zuida yingjia shi zhongguo nanzu? Qishi ta geng yingxiang zhongguo zhongdong zhanlve buju.” (“Do you think the Biggest Winner of Qatar’s Diplomatic Severance Crisis is China’s Soccer Team? In fact, it has more impact on China’s Strategic Situation in the Middle East”), Sohu, June 7, 2017. www.sohu.com/a/146953525_313480.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Wang Suolao. “kataer duanjiao fengboxia de zhongdong luanju.” (“The Chaotic Situation of the Middle East under the Qatar Diplomatic Severance Crisis”): 64.

[35] Jin Ruiting. “Jingti kataer duanjiao shijian dui ‘yidaiyilu’ jianshe de fumian chongji.” (“Sounding the Alarm over the Negative Impact of the Qatar Diplomatic Severance Event on the Construction of the Belt-Road”): 28.

[36] Ibid: 29.

[37] Mei Xinyu. “kataer duanjiao shijian yingxiang jihe.” (“The Various Aspects Influenced by the Qatar’s Diplomatic Severance Event”), Guoji Shangbao (International Commercial News), no. 7, June 12, 2017.

[38] For more in-depth analysis on these recent developments, please refer to: Saidy, Brahim. “Qatar and Rising China: An Evolving Partnership.” China Report, vol. 53 (4), November 14, 2017: 447 – 466.; Ahmed, Gafar K. “In Search of a Strategic Partnership: China-Qatar Energy Cooperation, from 1988 to 2015” chapter in Ed. Niblock, Tim & Galindo, Alejandra, & Sun, Degang. The Arab States of the Gulf and BRICS: New Strategic Partnerships in Politics and Economics. Gerlach Press, 2016: 192-206.

[39] Ulrichsen, Qatar and the Arab Spring: pp.42-43, p148.

[40] Al-Tamimi, Naser. “Qatar looks East: Growing importance of China’s LNG market.” Alarabiya, November 24, 2014. http://english.alarabiya.net/en/views/business/2014/11/24/Qatar-looks-East-Growing-importance-of-China-s-LNG-market.html; Ahmed, Gafar K., “In Search of Strategic Partnership: China-Qatar Energy Cooperation, from 1988 to 2015”: 199-203.

[41] “1 yue wodeguo tianranqi jinkouliang baochi kuaisu zengjia.” (“China’s Import of Natural Gas Increased Rapidly in January”), Zhongguo renmin gongheguo haiguan zongshu wangzhan (General Administration of Customs of the People’s Republic of China website), February 22, 2017. http://www.customs.gov.cn/publish/portal0/tab7841/info842175.htm.

[42] Ibid.

[43] “zhongguo tong kataer de guanxi (zuijin gengxin shijian: 2018nian 3yue).” [“China and Qatar’s Relationship (Recent Update: March 2018)”], Zhongguo renmin gongheguo waijiaobu wangzhan (People’s Republic of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs website), March 2018. www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/gjhdq_676201/gj_676203/yz_676205/1206_676596/sbgx_676600/.

[44] Zhang Jin. “kataer zhuquan caifu jijin yu ‘yidaiyilu’ zhanlvexiade zhongka jinrong hezuo.” (“Sino-Qatari Financial Cooperation under Qatar’s Sovereign Wealth Funds and the Belt Road Initiative Strategy”), Shanghai shifan daxue xuebao (Shanghai Normal University Academic Journal), no. 4, vol. 45., July 2016: 63-64.

[45] Jiang Yingmei. “kataer jingji fazhan zhanlve yu ‘yidaiyilu’ jianshe..” (“Qatar’s Economic Development Strategy and the Construction of the Belt Road”), Arab World Studies no. 6, November 2016: 36.

[46] Zambelis, Chris. “China and Qatar Forge a New Era of Relations around High Finance.” China Brief vol. 12, iss. 20, The Jamestown Foundation, October 19, 2012. https://jamestown.org/program/china-and-qatar-forge-a-new-era-of-relations-around-high-finance/

[47] Jiang Yingmei. “kataer jingji fazhan zhanlve yu ‘yidaiyilu’ jianshe.” (“Qatar’s Economic Development Strategy and the Construction of the Belt Road”): 42.

[48] Ibid.

[49] “al-safeer Li Chen: ziyarat sahib al-sumu lil-seen dashanat sharakah istratijiyya bayn ad-dawlatayn.” (“Ambassador Li Chen: The Visit of His Highness to China Inaugurated a Strategic Partnership between the two Countries”), Al-Sharq (The East), September 17, 2016. https://www.al-sharq.com/article/17/09/2016/السفير-لي-تشن-زيارة-صاحب-السمو-للصين-دشنت-شراكة-إستراتيجية-بين-الدولتين .

[50] “zhongguo tong kataer de guangxi (zuijin gengxin shijian: 2018nian 3yue).” [“China and Qatar’s Relationship (Recent Update: March 2018)”].

[51] “zhonghua renmin gongheguo he kataerguo guanyu jianli zhanlve huoban guanxi de lianhe shengming (quanwen).” “[With Regards to the People’s Republic of China and Qatar State’s Establishment of a Strategic Partnership Relationship Declaration (Full Text)].”, Zhongguo renmin gongheguo waijiaobu wangzhan (People’s Republic of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs website), November 3, 2014 www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/gjhdq_676201/gj_676203/yz_676205/1206_676596/1207_676608/t1206877.shtml

[52] Wood, Peter. “China-Qatar Relations in Perspective.” The Jamestown Foundation, July 7, 2017. https://jamestown.org/program/china-qatar-relations-perspective/

[53] Ramani, Samuel. “China’s Growing Security Relationship With Qatar.” The Diplomat, November 16, 2017. https://thediplomat.com/2017/11/chinas-growing-security-relationship-with-qatar/; Fulton, Jonathan. “China’s approach to the Gulf Dispute.” China Policy Institute: Analysis, May 3, 2018. https://cpianalysis.org/2018/05/03/chinas-approach-to-the-gulf-dispute/

[54] Karasik, Theodore and Cafiero, Giorgio. “Why China Sold Qatar the SY-400 Ballistic Missile System.” LobeLog, December 21, 2017. lobelog.com/why-china-sold-qatar-the-sy-400-ballistic-missile-system/

[55] “Afghan Taliban delegation visits China to discuss unrest: sources.” Reuters, July 30, 2016. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-election-opposition/turkish-opposition-candidate-for-president-tells-erdogan-lets-race-like-men-idUSKBN1I60KE

[56] Yang Guang. “zai zhongdong duojihua qushizhong xunqiu duobian hezuo.” (“Searching for Multilateral Cooperation in the Middle East’s Multipolar Trend”): 7.; Wang Suolao. “kataer duanjiao fengboxia de zhongdong luanju.” (“The Chaotic Situation of the Middle East under the Qatar Diplomatic Severance Crisis”): 64.; “Gao Youzhen: jiejue kataer duanjiao weiji, zhi shi shijian wenti.” (“Gao Youzhen: Solving the Qatar Diplomatic Severance Crisis is only an Issue of Time”).

[57] “wazir al-kharijiya yaltaqi mufakereen siniyeen.” (“The Foreign Minister Meets with Chinese Intellectuals”), Mawqi’ wizarat kharijiyat Qatar (Qatar’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs website), July 20, 2017. https://www.mofa.gov.qa/جميع-أخبار-الوزارة/التفاصيل/2017/07/20/وزير-الخارجية-يلتقي-مفكرين-صينيين.

[58] “al-seen lan tubqi ‘ala hiyadiyatha min al-azmah.” (“China will not Maintain its Neutrality in the Crisis”). Emarat Alyoum (Emirates Today), August 25, 2017. https://www.emaratalyoum.com/politics/news/2017-08-25-1.1022058.

[59] “Trump Sells Weapons to Qatar and Saudi Arabia as Gulf Dispute Drags On.” Newsweek, April 10, 2018. https://www.newsweek.com/trump-sells-weapons-qatar-and-saudi-arabia-gulf-dispute-drags-879855; “Qatar, Britain Finalize Deal for 24 Jet Fighters.” The Washington Post, December 10, 2017. https://www.wsj.com/articles/qatar-britain-finalize-deal-for-24-jet-fighters-1512930437; “Qatar, France Sign $14 Billion Weapons, Jet Deal.” Asharq Al-Awsat, December 8, 2017. https://aawsat.com/english/home/article/1107011/qatar-france-sign-14-billion-weapons-jets-deal; “Qatar Buys Italian Warshops as Persian Gulf Crisis Deepens.” The New York Times, August 2, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/02/world/middleeast/qatar-buys-italian-warships-as-persian-gulf-crisis-deepens.html

[60] “Al Jazeera English forced out of China.” Aljazeera, May 9, 2012. http://www.aljazeera.com/amp/news/asia-pacific/2012/05/201257195136608563.html

[61] “Al Jazeera launches website in Mandarin.” Aljazeera, January 1, 2018. https://www.aljazeera.com/amp/news/2018/01/al-jazeera-launches-mandarin-language-website-180101085619213.html

[62] “Gao Youzhen: jiejue kataer duanjiao weiji zhi shi shijian wenti.” (“Gao Youzhen: Solving the Qatar Diplomatic Severance Crisis is only an Issue of Time”).

About the author

Mohammed Turki Al-Sudairi is a Researcher at the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies and is currently pursuing his Ph.D in comparative politics at the University of Hong Kong. He holds a master’s degree in international relations from Peking University, and a degree in international history from the London School of Economics (LSE). Mohammed is a graduate of Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service. He is fluent in Arabic, English, and Mandarin. His research focuses on Sino-Middle Eastern relations, Islamic and leftist connections between East Asia and the Arab World, and Chinese politics.