By Clemens Chay

In his remarks at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, the Qatari Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Defence, Khalid bin Mohamed Al Attiyah, denounced what he called a “game of one-upmanship” in foreign policy which “leaves many isolated”. Instead, he called for an inclusive and sustainable model. This model has given rise to a series of reconciliatory moves in the Gulf since the Al-Ula summit in January 2021, which restored diplomatic relations between the blockading quartet (Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Egypt) and Doha, and provided momentum for engagement with traditional adversaries.

Besides improved ties with Turkey, the Gulf countries’ typically problematic relationship with Iran has also been looking up. The UAE’s National Security Adviser, Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed, met the head of Iran’s Supreme National Council last December, while recurring Saudi-Iranian talks in Baghdad have sparked some optimism, with a foreign ministry spokesperson in Tehran recently insisting that “both sides are interested in a continuation of the meetings”. The post-blockade status of Qatar-Iran ties has been boosted – the February trip to Doha by President Ebrahim Raisi was notable. Since then, numerous high-level meetings, phone calls and consultations on the sidelines have culminated in Qatar’s mediating role in the JCPOA talks and, more importantly, advances on the business front.

The inclusivity manifested at the regional level can be put down to the perceived US disengagement from the region and, at a broader level, to the unwillingness of external powers to get entangled in conflicts – whether hot or cold. Inclusivity is thus a “self-help” mechanism by the Gulf states as they seek not just stronger intra-bloc ties, but also a thaw with long-time foes. This harks back to the words of former US President Barack Obama, who said that Riyadh and Tehran need to “find an effective way to share the neighbourhood and institute some sort of cold peace”. In this context, Qatar and Iran’s deepening ties are a noteworthy signpost of how far things have come: Just five years ago, the Riyadh-led quartet against Doha demanded that ties between the two be cut. This was among the 13 demands laid down by the blockading quartet. Now, we are not just witnessing a reversal of that situation, but also efforts to take the relationship further – without pushback from Qatar’s neighbours. From Tehran’s point of view, the bilateral relationship brings optimism that it can re-negotiate its ties with the other Gulf states – or, as the Iranian Foreign Minister put it, “accelerate mutual cooperation with neighbours”.

From G2G to B2B Relationships

During President Raisi’s two-day visit to Qatar, 14 agreements relating to trade, cultural and media co-operation were signed, signalling a comprehensive approach to the deepening of ties. The visit was symbolic: It was Mr Raisi’s second overseas trip after his election, and his first to an Arab country. Among the more notable deals was a proposed tunnel project that aims to connect the Iranian port town of Deyyar to Qatar, subject to feasibility studies. If built, the tunnel will add an extra dimension to already strong air transport links following Qatar Airways’ use of Iranian airspace during the blockade.

Mr Raisi’s trip to Doha laid the groundwork for further cooperation in the business and tourism sectors, guaranteeing that cooperation at the highest political echelons is translated into sectoral development. In April, the Qatari Minister of Commerce and Industry, Jassim bin Saif Al-Sulaiti, was received by Iran’s Roads Minister, Rostam Ghasemi, on the resort island of Kish, concluding a deal that linked Doha’s Flight Information Region (FIR) with that of Tehran’s. The more immediate purpose of this agreement is linked to the upcoming FIFA World Cup. Infrastructural plans coordinated by both sides aim to use the Iranian islands of Qeshm and Kish for visiting fans, with Tehran prepared to waive visit visas during the tournament. A marine tourist line is also expected to be inaugurated, connecting the ports of Bushehr in Iran and Qatar’s Hamad. In personal correspondence with the author, Mehran Haghirian, the Director of Regional Initiatives at Bourse & Bazaar Foundation, a British think-tank, explained that Iran’s role in the World Cup is an example of Qatar’s “constructive engagement” with regional neighbours – in other words, spreading the wealth to gain goodwill.

Crucially, there is real intent by both countries to constantly push the boundaries in trade relations. Qatar’s imports from Iran peaked in 2018 – exceeding US$400 million – before slowing down over the next two years as a result of the US “maximum pressure” campaign against Tehran. But since 2020, trade has grown. Qatar’s Minister of Commerce and Industry, Sheikh Mohammed bin Hamad Al Thani, said during the latest session of the Qatari-Iranian Joint Committee, in June, that bilateral trade exchanges grew by 34 per cent in 2021. This echoes President Raisi’s ambitions: The Iranian leader told the Qatari Business Association (QBA) of his plans to raise the bilateral trade exchange to US$1 billion. Since then, a Joint Trade Council has been formed, which in turn paved the way for the launch of an Iranian business centre in Qatar. The head of Iran’s Trade Promotion Organisation, Alireza Peyman-Pak, noted that transportation and banking relations will be key planks of the drive to improve trade. As intra-regional economic competition heats up, a forecast by The Economist Intelligence Unit noted that stronger Qatar-Iran relations will bolster Doha’s efforts to “challenge Dubai’s position as Iran’s gateway to the Gulf Cooperation Council region”.

The geopolitics of Utility in a Cooling Climate

The season of rapprochement, beginning with the Al-Ula reconciliation in January 2021, has resulted in a more measured approach towards the region by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman. His desire to engage both partners and adversaries sends a signal to Riyadh’s neighbours that they can follow suit. Indeed, the 14 deals signed during his trip to Cairo in June coincided with the ratification of the Qatar-Egypt MoU on the sidelines of the Qatar Economic Forum. A week later, another bilateral MoU emerged from Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el Sisi’s trip to Muscat, indicating some measure of regional coordination.

Further indications of ongoing regional détente this year include a host of cooperation agreements signed between Oman and Iran, and the first meeting between Qatari and Emirati leaders since the rift. More recently, Bahrain – the last holdout among the blockading quartet – has returned to the fold after a meeting between the two sides at the GCC+3 summit. In a piece for Foreign Policy, Danielle Pletka, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, wrote that the Gulf states are “hedging their bets against US power, playing footsie with Iran […] and otherwise acting like, well, Qatar”. Tehran’s willingness to “take advantage of Gulf hedging”, she added, does not signify a break from its own ambitions, but underscores a “willingness to play the game that Qatar copyrighted”. This echoes a cryptic message that one Qatari diplomat had for the author: “If you engage them, you keep them at bay.”

Crucially, each Gulf state prefers to deal with Iran at its own pace, and on its own terms. This is evident from the cool reception given to a proposed air defence alliance during US President Joe Biden’s recent visit to the region. When the idea was floated, Saudi Foreign Minister Faisal bin Farhan responded that “this is not on the table”, while the adviser to the UAE president, Anwar Gargash, said that Abu Dhabi is “not part of any axis against Iran”. These reactions suggest that firstly, the Gulf states consider it foolhardy to enter into a provocative alliance against Tehran following efforts at political de-escalation, and secondly, that there is, as Abdulkhaleq Abdulla, a former adviser to the UAE leadership, put it during a virtual roundtable, “no shared vision on how to counter Iran”. This continues from the failure of the Middle East Strategic Alliance (MESA), announced during the Trump administration, which is aimed at tackling a thorny Tehran, but “suffers from expectation and confidence gaps”, as Yasmin Farouk, a non-resident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, put it. The cooling of regional relations, coupled with a general preference for bilateral engagements, only offers more room for Qatar and Iran to make further headway in their diplomatic relationship.

Vying for Recognition, or Operating Rationally?

Returning to the Qatari Deputy Prime Minister’s remarks at the Shangri-La Dialogue, which touched on Qatar’s “balancing game” – a term used by external observers – he was adamant that Doha “simply does not play any games”. Instead, he said, “we know who we are, our shortcomings, and what we stand for through our peacebook roadmap”. While it is difficult to separate Qatar’s hedging strategy from its foreign policy, a question arises about its motivations.

Is Doha’s quest a bid for diplomatic prestige, or a realistic move? Qatar’s latest involvement in the JCPOA talks is a case in point. While mechanisms and procedures for discussions already exist between the US and Iran, brokered by the EU (or, more precisely, the EU3+3), Qatar has entered the scene as an eager mediator. Although that round of talks concluded with “no progress made”, the Iranian Foreign Minister, Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, remained positive in his assessment, while Doha continues to send senior officials to Tehran in an effort to move things along. The emirate’s efforts came after it was designated a Major Non-Nato Ally (MNNA) by the US in January. Beyond symbolism, this elevation of status confers a variety of security cooperation advantages, as R. Clarke Cooper, a former US Assistant Secretary of State for Political-Military Affairs, wrote for The Atlantic Council, but will also “increase expectations on Doha to seek stability” in the region.

In other words, Qatar is expected to show its usefulness. A retired senior Qatari official, speaking to the author on condition of anonymity, remarked that it is nothing new for Qatar to convey messages between conflicting parties, but the timing of Doha’s new MNNA status was “President Biden’s way of saying thanks for its help in facilitating the withdrawal from Afghanistan, including the repatriation of Americans”. Since then, Doha has continued communications with the Taliban, helped to facilitate prisoner swaps between Tehran and Washington, and has agreed to review mechanisms for the release of some of Iran’s frozen funds.

For Iran, the diminished regional appetite for conflict allows the regime to not only remain on working terms with long-time rivals, but also reinforces its claim that it is business as usual in Tehran (as opposed to international isolation). Speaking to Al Jazeera, the head of Tehran’s Strategic Foreign Relations Council, Seyed Kamal Kharrazi, reiterated his country’s “support for a regional dialogue” with the likes of the Gulf states, Egypt, and Turkey. Crucially, opportunism in the face of conflict also offers precious and lucrative opportunities. Against the backdrop of the Russia-Ukraine crisis, the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) has signed a deal with Russian gas producer Gazprom. Yet, right in Tehran’s backyard is the world’s largest natural gas field, the South Pars/North Dome one. Given that this field is shared with Qatar, the need to “maintain open lines of communication and good relations over the issue of gas production” is, as Mehran Kamrava, a professor of government at Georgetown University, told the author in personal correspondence, more strategic than ever.

The reality is that the changing Middle Eastern landscape comprises pro-active countries that are now willing to engage diplomatically with long-time rivals. Despite lingering suspicions, an atmosphere of de-escalation will only encourage a warming of various bilateral ties, including that between Qatar and Iran. It is also testament to the rise of local, regional powers, as tweeted by the Emeritus Professor of International Relations at Sciences Po Paris, Ghassan Salamé, who affirmed that “the concept that the Middle East is a void that needs to be filled by one great power, so other great powers do not fill it, is largely obsolete”. Instead, as they deal with the reluctance of outside powers to invest blood and treasure in the region, the Gulf states themselves are seeking to become military and diplomatic powerbrokers in their own backyard.

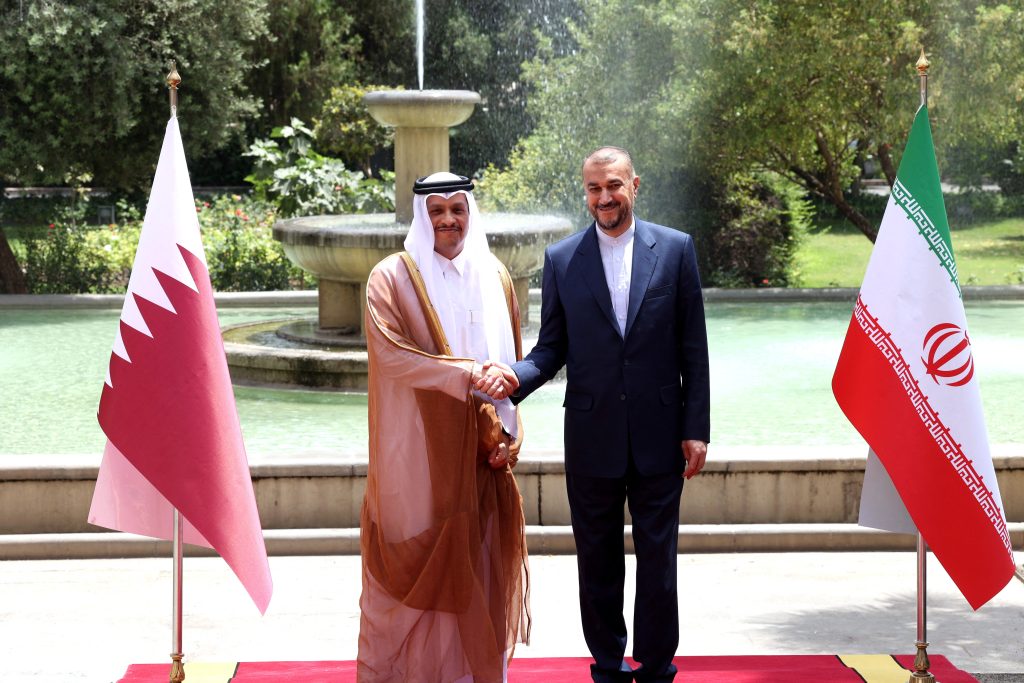

Image Caption: (R to L) Iran’s Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian receives Qatar’s Foreign Minister Mohammed bin Abdulrahman bin Jassim al-Thani at the foreign ministry headquarters in the capital Tehran on July 7, 2022. Photo: ATTA KENARE / AFP

About the Author

Dr Clemens Chay is a research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute. His research focuses on the history and politics of the Gulf states, with a particular emphasis on Kuwait, Oman and Qatar. At MEI he spearheads a public education series entitled “Bridging the Gulf”. His recent academic publications include a chapter that examines Kuwait’s parliamentary politics in The Routledge Handbook of Persian Gulf Politics (2020), a chapter in the edited volume Informal Politics in the Middle East (Hurst, 2021), and a study appearing in the Journal of Arabian Studies, titled “The Dīwāniyya Tradition in Modern Kuwait: An Interlinked Space and Practice.” His commentaries also feature across different outlets, including ISPI, KFCRIS, and AGSIW. He is currently working on a book project related to Kuwait’s diwaniyas (affectionately known as diwawin, and more widely known as majalis outside Kuwait), the reception rooms for informal meetings that have implications for society, politics and diplomacy.

Prior to joining MEI, Dr Chay was the Al-Sabah fellow at Durham University, where he taught and completed his PhD in Middle Eastern and Islamic studies, and where he also received an MSc in defence, development and diplomacy. He is also a Sciences Po Paris alumnus, having read his BA at the Menton campus.