Introduction

After an initial phase in which analysts expected the Gulf Cooperation Council’s (GCC) fiscal cushions to ward off the global economic crisis, the world recession has started to reverberate in the Gulf.[1] The Gulf monarchies are in some ways better, but in other ways worse, equipped to ride out the storm. As many strategic assets remain in state hands, Gulf countries do not have to go through a painful period of nationalisation, but can react in a more immediate and nationally-coordinated fashion to market failures. The crisis has nonetheless highlighted key institutional weaknesses of the GCC countries.

Why are the Gulf Countries So Strongly Affected Despite Their Large Capital Surpluses?

The Gulf monarchies have pursued an idiosyncratic development model: they are pro-capitalist, outward-oriented and deeply integrated with the global economy, yet at the same time comprise large welfare states and play a heavy role in key economic sectors through direct ownership of many of the largest companies.

Much of this mix is explained with the rentier nature of the regimes. They have historically had much larger resources available than the local private sector to push large-scale development, and their surpluses have allowed them to be both generous visà-vis their national populations and developmentalist in their economic policies. The mix is also explained with the political sociology of the regimes, i.e. conservative monarchies with strong historical bonds to local merchant classes, deep local traditions of international trade, a pro-Western orientation, and the absence of nationalist social revolutions that most other Middle Eastern states have gone through.

The mixture of state-led development and patrimonial monarchy in many regards delimits how the Gulf monarchies can react to the global economic crisis, and it imparts to them an internationally unique mixture of weaknesses and strengths.

To different degrees, all of the Gulf monarchies suffer from a lack of institutional accountability and relatively opaque bureaucratic and regulatory structures. In some cases, as in Dubai, the system is very much centred around one powerful ruler and information about governance structures or fiscal policy is limited. Such systems are particularly prone to non-transparent and risky investment strategies at times of boom, and crises of confidence and capital flight in times of bust. A manageable degree of economic contagion through lower oil prices and illiquid international capital markets has hence in some cases escalated into a deeper crisis.

On the other hand, the Gulf monarchies in most cases command not only very large fiscal resources to carry them through the crisis, but also have direct control over

significant parts of the economy. It is much easier to influence and prop up, or nationalise, businesses which are already partly or wholly state-owned.

To some extent, one might argue that the GCC states have leapfrogged into a new age in which government ownership and involvement will once again play a larger role in capitalist economies. They have done so in very different ways, however. Dubai has embarked on a high-risk, high-leverage diversification with state-owned enterprises (SOEs) catering to the international logistics and tourism markets. Saudi Arabia has seen a slower, steadier state-led development process in which heavy industry assets, particularly Saudi Arabian Heavy Industries Company (SABIC), has played a leading role.

Others such as Abu Dhabi and Qatar have only just started to embark on a path of state-led diversification, mixing the Dubai and Saudi strategies to varying degrees. Kuwait is the only rich GCC country that has not managed to build up profitable state assets, as its regime has been less autonomous from populist social demands than the others. Development in Kuwait has been more strongly led by the private sector, but business there has suffered from governance and risk management problems rather similar to those that Dubai’s SOEs are struggling with now, without the strategic benefit of direct state control and support.

This institutional landscape has conditioned the effects and the reactions to the global economic crisis differently in different GCC countries, as reflected in the different sectoral crises they are witnessing currently.

Impacts on Specific Markets

Real Estate

As in the US and the UK, real estate is the one of the hardest-hit sectors. In autumn 2008, an estimated US$2,500 billion worth of projects were either planned or under way in the GCC, the majority of which would have been in the real estate sector. Perhaps 60% of these have been shelved now. Exposure to and the nature of real estate investments differ strongly from one market to the other. While the real estate collapse has hit Dubai very heavily, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Qatar have seen smaller price collapses in a sector that is much less important to total national growth. Bahrain is somewhere in between.

Dubai

Dubai’s real estate sector had all the makings of a bubble, with its share in GDP increasing from an estimated 10% in 2005 to about 18% in 2007. Recently, numerous ambitious projects catering to an international audience have been cancelled. Many buyers are insolvent and/or are leaving the country (in late 2008, some 40% were reportedly late on their payments), and smaller developers are facing bankruptcy. Prices have fallen by an estimated 40% from their peak last year and are likely to fall further in the next two years. The value of construction contracts awarded in the UAE fell by 85% in the fourth quarter of 2008 compared to the same period in 2007, and the end-user market has become very thin.

Its real estate market, however, is by and large an oligopoly, as governmentowned SOEs such as Emaar and Nakheel play a dominant role. According to one estimate, 70% of real estate in Dubai is under Emaar’s control. These organisations are controlled by a small group of individuals close to Dubai’s ruler. This makes coordination of supply and pricing easy and allows the government to keep assets off the market to balance supply and demand. Where a larger number of private businesses would face formidable collective action problems, the developmental dictatorship of Dubai can coordinate the activities of its SOEs from a strategic angle.

This is not to say that the realty market in Dubai is not illiquid and that prices have not collapsed, but the situation is considerably better than it would be if the real estate sector were driven mostly by private developers (as it was for example in Japan in the late 1980s).

Nevertheless, Dubai’s SOEs are themselves seriously struggling now , as they are much more exposed to international credit markets than most other Gulf SOEs, and Dubai’s fiscal resources are rather small. They also have been catering to a volatile international audience more exclusively than the SOEs of other Gulf states. Dubai’s higher level of international integration, once seen as hallmark of progress, has now become deeply problematic. Combined with governance structures that are opaque even by GCC standards, this has sapped much of the international credibility that Dubai once had.

The demographic impact of the current crisis is also much larger in Dubai than in any other GCC state, as the real estate collapse has created a vicious feedback loop. As the sector employs fewer people, out-migration sets in, decreasing demand for property, which in turn leads to further layoffs. Pre-boom data from the 2005 census indicates that 48% of the total workforce of about one million were active in the construction and real estate sector compared to about 12% in Saudi Arabia.

Driving through Dubai’s streets in February 2009, one could not but notice the relative calm compared to the situation a few months earlier. UBS expects an 8% population loss in Dubai in 2009 and estimates that if the property-related labour force declines by 20% this year and 10% next year, there will be a housing oversupply of 87,000 units, or 27% of total stock in Dubai, by the end of 2010.

The fact that Dubai caters to a footloose audience in tourism and retail as well magnifies the effects of both domestic and international economic volatility, and leads to higher price elasticities, which probably explain some of the desperate rebate policies by its hotels and shops. With no large “captive audience” of nationals such as Saudi Arabia, Dubai would suffer strongly now even if it had done everything right.

Developers are now relaxing payment plans and the government is now willing to grant residency visas to property buyers – long a bone of contention between developers and the immigration authorities. These measures will not stanch the population outflow.

Other Countries

Oman and Saudi Arabia never enjoyed real estate growth on the level of Dubai that could have led to a large bubble. Thanks to stronger regulation by the Saudi central bank and the absence of a mortgage law, lending practices of Saudi banks have been much more cautious, and due to relatively lower inflation, real interest rates have not been quite as low as in the UAE. As important, the real estate share in Saudi GDP is much smaller at 5%, compared to (recently) almost 20% in Dubai.

The situation in Qatar is somewhat less stable, as the real estate exposure of its banks seems to have been higher and more residents rely on the sector for their jobs. A recent decline in prices has been reported. However, continuing large-scale developments in oil, gas and heavy industry, will continue to provide significant demand for residential property. In any case, some of the most significant property companies, such as Diar and Barwa, are state-controlled and hence allow for top-down supply management.

In Bahrain, there are also signs of some overheating. Land transactions have been growing at similar rate as in Dubai. The share of the sector in GDP is smaller, however, at around 8%. The impact of the cooling period which seems to have begun in the second half of 2008 will be less severe.

Some of the construction spending in the GCC countries does not go into end-user real estate but rather national infrastructure – less so in Dubai, but very much so in Saudi Arabia, where the state’s project spending in the 2009 budget amounts to US$60 billion alone, almost half of total state expenditure. State infrastructural projects will in most cases continue to be implemented. They might see some delays – such as Bahrain’s US$2.2 billion power plant joint venture – but these delays will be used to re-assess and re-negotiate rather than to cancel agreements.

Workforce in Construction and Realty Sector (2007)

| Dubai | Oman | Qatar | KSA | UAE | |

| Construction | 43.52% | 37.31% | 35.15% | 8.48% | 13.91% |

| Real Estate Services | 6.74% | 2.50% | 2.54% | 3.57% | 2.03% |

| Total | 50.26% | 39.80% | 37.70% | 12.05% | 15.94% |

Source: Markaz

Banking and Capital Markets

Initial hopes that the crisis would bypass financial sectors in the Gulf – which led to London and New York bankers sending their resumes to Dubai – did not last long. GCC banking and finance is the other sector that has suffered the most from the international crisis. This is linked to GCC banks’ exposure to real estate markets and the drying up of international liquidity, but also to the relative opacity of some of the regional markets. Again, the government’s capacity to react has had much to do with their strong direct presence in the market.

The Gulf has seen another round of stock market crashes since 2008, following on the heels of even larger crashes in 2006. How is this to be explained, given that local business has been doing well and fiscal resources in most cases have been ample? Weak regulation is part of the answer, as is the limited “free float”, which is to some extent the result of the large, non-traded proportion of shares owned by GCC governments. Low transparency has induced herd behaviour and has caused local investors to either exit or to sit tight and remain idle. In some cases, such as in Kuwait, traded holding companies have also been strongly exposed to international financial markets through risky investments, and in the UAE, international investors have withdrawn a significant share of their liquid assets (more than US$50 billion were reportedly withdrawn from the UAE by December 2008).

Smaller investors have been hit harder by this collapse, but this has thus far had few direct political repercussions. The exception is more politicised Kuwait, where investors have been mobilising to ask for government bailouts, and have even managed to make a court temporarily halt trading on the local bourse.

After explosive growth of money and credit up to 2008, liquidity on banking markets is now pretty tight. This is true both for large, syndicated loans – in which international banks still tend to dominate – and for consumer and smaller business loans. According to an Apicorp estimate, the MENA region saw more than US$150 billion of bonds and syndicated loans issued in 2007, which decreased to about US$100 billion in 2008. Less than US$50 billion are expected in 2009.

Government Reactions

Although governments’ reactions to the financial slow-down have differed, in many cases, regimes have followed their “rentier reflexes” of sometimes indiscriminate distribution. While in the current situation, fiscal generosity in general makes both economic and political sense, financial sector bailouts and stock market interventions are less economically rational. In Kuwait, where political pressure to prop up stock prices has been high, the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA) has made significant direct purchases on the stock market – not enough to stabilise it, but possibly enough to create future moral hazard problems. That the KIA might become politicised is a worrying trend. Oman has also created a dedicated fund for stock market interventions.

More generally, all central banks have intervened to provide domestic banks with cheap credit, which in some cases has been converted to capital. The latter, again, is a less radical step in cases like Qatar National Bank or Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank, which already had significant state shareholdings. Although banks in some cases have been over-leveraged, the GCC governments are in a good position to stabilise the sector in the mid-term, drawing on considerable resources and generally sound central bank structures. Capital-rich countries such as Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi in particular have found it easy to stabilise their banking systems. It was no coincidence that cash-strapped Dubai’s bank ratings went down just after Abu Dhabi had announced to lend money to its own banks via Tier 1 capital notes.

Kuwait Finance

The least necessary financial crash was probably the one in Kuwait, a country that is much less exposed to volatile, internationalised service sectors than Dubai and commands much larger capital resources. Its financial market is large, but weakly regulated. Once again, for political reasons, there is no independent stock market regulator as in neighbouring states.

Several of Kuwait’s private investment banks and asset management firms have been deeply involved in derivatives and other complex financial instruments, and were strongly leveraged. As a result, Global Investment House has defaulted on its loans, and Gulf Bank had to issue new shares with KIA guaranteeing their purchase. The market is illiquid now. Several large business families are struggling to remain solvent, and trust is low. With a stronger regulatory tradition as in Saudi Arabia, this situation could have been avoided. Gulf banks have generally engaged in less proprietary trading (i.e. speculation with their own capital) than many banks in the West, but Kuwait seems to be a significant exception.

Other Cases

Dubai’s financial sector has strongly relied on both international capital inflows and the local real estate market, resulting in a double blow to Dubai banks. The hopes to make the emirate a global hub for financial services will not be borne out in the near future, and many local investors now see Dubai’s attempts to introduce innovative financial instruments as misguided. Dubai banks’ real estate exposure was officially limited to 20%, but many general business and personal loans have probably been reinvested in realty projects, reflecting relatively weak banking regulation in the UAE federation. This also explains some of the troubles of Abu Dhabi banks, which however are much easier to bail out by the emirate’s government.

Saudi banks have probably weathered the storm the best so far. Their returns have decreased in some cases, but only some of the smaller ones have made losses in the last quarter of 2008. For the full year, all have reported gains. A strong and conservative tradition of regulation by SAMA, the central bank, has prevented speculative excess, and has kept loan-to-deposit ratios below 80%, while in other places they have veered towards 100%. Saudi banks have the largest domestic market, and the kingdom has been the least globalised of the six GCC countries. It has hence been the least affected.

Upstream Energy and Heavy Industry

Based on low oil prices and the difficulty to obtain large project loans internationally, one might expect upstream oil, gas and heavy industry to suffer particularly harshly from the current crisis. This is not quite the case, however, for a number of reasons. First, most of the states have accumulated vast reserves since 2003 which now allow them to see through projects with relatively limited leverage. Technocrats are also aware of the fact that the oil market is likely to become tighter again in a few years, and know that they need to be ready for this moment to avoid excessive price spikes as in 2008. Some upstream projects have slowed down or been cancelled, but the ones under way are generally seen through. Again, the fact that national oil companies are state-owned gives them an in-built advantage in terms of creditworthiness and capability to plan for the long run without being pressured by shareholders looking for short-term results. In the mid-term, however, an oil price of US$75 is likely to be needed to maintain sufficient upstream investment. If that is not attained, significant global oil shortages and price spikes can be expected 5-10 years further down the road.

The short-term impact of the crisis on product prices in petrochemicals, aluminium, steel, and refining has been devastating. Saudi Arabia’s SABIC – which has been profitable ever since its plants came on stream in the 1980s – is expected to record a loss in the first quarter of 2009. It is now more exposed to international markets than before by virtue of the European and American assets which it has picked up in recent years, notably GE Plastics, which was acquired for US$11.6 billion in 2007 at a time of high prices. In December 2008, mining giant Rio Tinto backed out of its aluminium joint venture with state-owned Maaden in Saudi Arabia. The stepped-up internationalisation efforts of Gulf SOEs seem to have damaged them in the short run.

They are however likely to suffer less than most heavy industry players in the rest of the world, as they continue to enjoy local feedstock advantages; are backed by states with very deep pockets; and can afford to plan for the long run. It is true that a number of speculative industry projects – especially those involving large private investors – have been put on hold, but in many cases their viability was in question anyway due to a shortage of gas feedstock in the GCC. It is likely that the established heavy industry champions can ride out the current crisis.

As in other parts of the world, many agreements are likely to be re-negotiated, and some state-supported projects, like the petrochemicals joint venture between Qatar Holding and South Korea’s Honam, have been put on hold. This represents a consolidation rather than a crash, however.

A larger role for the private sector in heavy industry will probably take longer to emerge than anticipated, as private businesses have deeper problems of creditworthiness and financing than SOEs; have lost much of their appetite for risk; and are more shortterm oriented.

The crisis has also thrown some doubt on Saudi Arabia’s new economic cities, some of which are supposed to incorporate a heavy industrial component. Offering similar infrastructure to Dubai’s free zones, they are unlikely to have the same regulatory autonomy and, crucially, are supposed to be almost completely private sector-financed. This does not appear a very attractive proposition in current circumstances. Some of the biggest investors in the Gulf like Saudi Arabia’s Prince Waleed or Kuwait’s Nasser Al-Khorafi, potentially large enough for world-scale industrial investment, have lost much money and are heavily stretched.

The biggest reversal in the field of heavy industry so far has been Kuwait’s abortion of the US$17.4 billion petrochemicals joint venture with Dow. Although a withdrawal from or re-negotiation of the project might in fact have been rational, the process was beset by so much unpredictable political bickering and parliamentary grandstanding that it has done further damage to Kuwait’s credibility.

Impact on Oil Income and Fiscal Policies

The short-term impact of the crisis on fiscal policy is likely to be very limited. The oil income of GCC states is estimated to drop by about 40% in 2009, and nominal GDP might drop by 10-15%, but this will not affect spending policies. Even if oil income collapsed completely, reserves would in most cases be sufficient to cover several annual budgets.

Budget breakeven points are variously estimated between US$50 and US$60 per barrel, and most states are likely to incur deficits in 2009, which have been estimated at an average of about 5% of GDP (compared to a 30% surplus in 2008). None of this is as dramatic as the budgetary crisis in the mid-1980s, when state spending had tracked the increase in oil income much more closely and reserves therefore were much smaller when oil prices collapsed. From 1969 to 1976, Saudi government income and expenditure both grew at an annualised rate of around 55%. From 2002 to 2008, by contrast, income grew by 32% per year, while expenditure only grew by 14%.

Most government budgets for 2009 are expansionary, pursuing a deliberately counter-cyclical policy to soften the blow of the crisis. Saudi Arabia is pursuing a particularly vigorous expansion policy with a 36% increase in project spending. Only Kuwait’s government has not yet managed to push through a fiscal package to counter the crisis. The large reduction in Kuwait’s budget in 2009 is caused by a big one-off payment to the Kuwaiti pensions fund in 2008. Even taking account of this, however, there remains shrinkage of more than 10% in 2009.

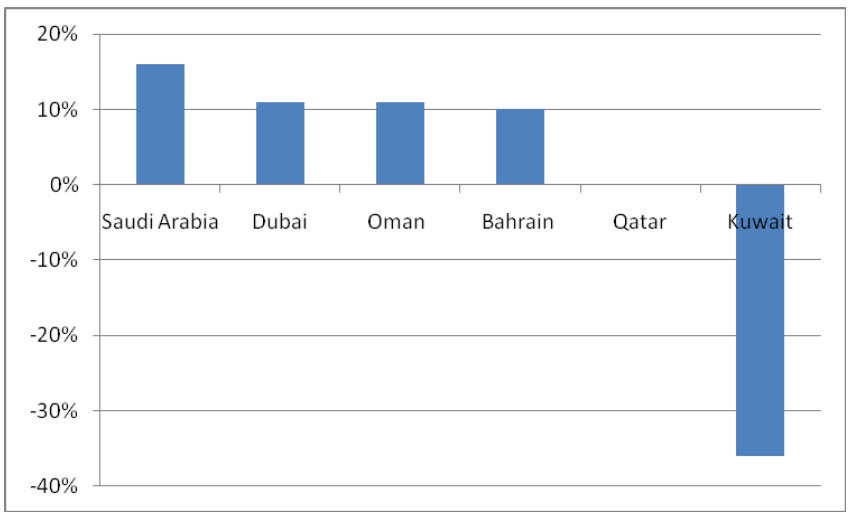

Change in Government Budget Size 2009 over 2008

Source: Markaz/Kuwait

Even under the worst oil price scenarios, the richest GCC economies – Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar and Abu Dhabi – will be able to maintain or increase their levels of spending for many years. Saudi Arabia has enough overseas reserves to pay for four complete annual budgets without drawing on any other income. Bahrain’s and Oman’s overseas resources are much smaller, but their budgetary needs are also more modest. Neither is leveraged as heavily as Dubai, whose SOEs are heavily indebted and whose overseas assets have suffered badly during the slump.

Econometric analysis on Saudi Arabia has shown that the oil price affects business confidence not only indirectly by influencing state spending, it also has a direct impact on investment behaviour that is almost as strong as the effect of spending itself. This means that the oil price collapse probably puts an additional damper on business activities even if states continue to increase their outlays.

As spare capacity on the international oil market is much lower than in the 1980s, however, and is mostly controlled by Saudi Arabia, in the mid-term oil prices are likely to increase again. With the exception of Dubai, the GCC economies probably have enough staying power to survive the current low-price period without major damage.

Is There Any Political Impact?

The economic crisis has so far had a remarkably limited political impact on the Gulf countries. There are only two major exceptions: the domestic political crisis in Kuwait, which the economic slump has exacerbated; and the power relations between Abu Dhabi and Dubai, which have strongly shifted in Abu Dhabi’s favour. .

In Kuwait, the global slump has highlighted the existing political stalemate between government and parliament by greatly increasing its political and economic cost. The crisis has contributed to the recent dissolution of parliament. Due to the plethora of populist demands for direct handouts and consumer loan write-offs, it had been impossible to assemble a coherent rescue package. The government will now probably issue a fiscal stimulus package by decree, but as a new parliament will have to be elected within two months, this is only a stopgap measure unlikely to overcome the basic stalemate that the emirate finds itself in.

Dubai is the one player in the Gulf that has built very large SOEs on the basis of limited fiscal resources. Its companies are more leveraged than any other public companies in the Gulf and their credit ratings have repeatedly been downgraded since summer 2008. Government and government-controlled entities have total debt of about US$80 billion, which is almost double its GDP. According to Mohammad al-Abbar, head of Dubai’s Department of Economic Development, government-controlled assets amounted to US$360 billion, but it is not clear how this figure has been calculated. It is likely to include a large share of illiquid infrastructure and real estate assets.

Dubai has had to call on its richer neighbour, Abu Dhabi, to bail it out. In November 2008, it was announced that the new Abu Dhabi-financed Emirates Development Bank would absorb Amlak and Tamweel, two large Islamic lenders heavily involved in Dubai real estate.

In February 2009, Dubai issued a US$20 billion bond programme, of which the UAE central bank, supported by Abu Dhabi, immediately picked up US$10 billion. With a 4% interest rate that would have been impossible to obtain internationally, this amounted to a bailout, as Dubai would otherwise have struggled to cope with its refinancing requirements for 2009, which are estimated at US$14-15 billion or more.

Dubai is likely to face further financing problems in 2010 and beyond, and it is likely that Abu Dhabi would step in again to help, as a total collapse of the Dubai economy is not in Abu Dhabi’s interest. It is not clear whether the Abu Dhabi government or the ruling family will take over management interests in Dubai assets in return for their support, as they have in the past been happy to act as passive investors. The recent transfer of the Burj Al-Arab hotel to a member of the Abu Dhabi ruling family might constitute an exception.

It is however clear that the political balance between the two emirates has already shifted and Dubai is likely now to require clearance for major policy decisions from its larger neighbour. This could result in a Hong-Kong-type scenario, in which Abu Dhabi as an external power exerts broader political control, but leaves economic management to local elites in order to retain Dubai’s entrepot status, from which Abu Dhabi elites have also profited.

This is broadly in line with the pre-existing division of labour between the two emirates, in which Abu Dhabi took care of federal politics and international relations, while Dubai focused on commerce. One level on which this will impinge on Dubai’s commercial strategy is by reducing its trade and investment linkages with Iran, which have come under much pressure. It remains to be seen whether Abu Dhabi will also force Dubai to leave more space for its own logistics and transport ventures such as Etihad Airways or the new Khalifa port.

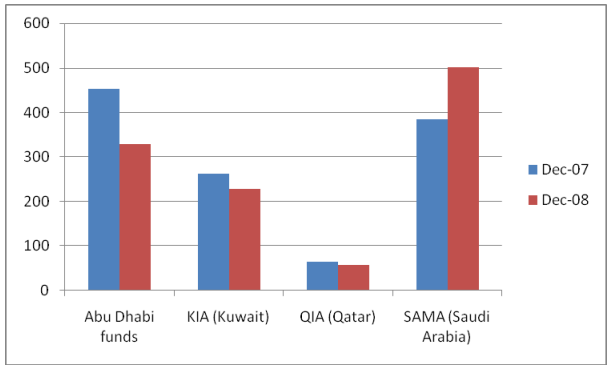

Assessing the Crisis’ Differential Impact by Sovereign Wealth Funds

Different sovereign wealth funds (SWF) have been affected to different degrees by the crisis. Abu Dhabi and Qatar are estimated to have lost some 40% of the portfolio they held in December 2007, and Kuwait some 36% – losses these governments have been unable to offset with the massive additional revenues of 2008. Only Saudi Arabia has increased its assets in 2009 thanks to SAMA’s very conservative investment strategy.

Estimated Volumes of GCC Official Overseas Assets

Source: Setzer/Ziemba, Council on Foreign Relations, January 2009

Qatar’s SWF in particular has engaged in a number of leveraged deals that have left it cash-strapped. Only Dubai’s smaller funds (such as Istithmar and DIC) have used higher leverage. The latter’s plans to become “funds of funds” by managing other SWFs’ assets are now obsolete.

The losses of Abu Dhabi and Kuwait appear less spectacular if we take into account the purpose of their SWFs: long-term wealth accumulation. If we assume that global asset markets will in the long run behave as they did during the 20th century – i.e. stocks and other riskier investments provide higher average long-term returns than fixed-income assets – then the current crisis might only be a temporary setback. In any case, the recent losses pose no threat to the solvency of these countries. The situation in Qatar appears a bit more difficult, but still poses no existential threat thanks to the country’s high oil and gas revenues. Dubai, which now has large needs of short-term financing, is a different story. Its risky overseas strategies arguably were ill-suited to a state with limited fiscal resources and high amounts of leverage in its public sector.

In the short term, all of the SWFs have participated in the recent “flight to quality”, i.e. into government bonds and dollar assets. In the mid-term, they are likely to return to emerging markets, which will take a gradually increasing share in their portfolio. Asia will play a particularly large role in this. Different funds will keep different ratios of assets, however, with SAMA remaining more conservative than the others.

Conclusions

The Gulf has not seen any failures on the scale of AIG or Lehmann Brothers, but several big private players, and some of Dubai’s SOEs, are in trouble. To some extent, the current crisis will allow a healthy weeding out of unsustainable finance and real estate companies, and will take some of the froth off the market. Some of the corrections were indeed timely, as there was risk of overcapacity in real estate and heavy industry, and the contracting sector suffered from bottlenecks and very high labour and input prices. Projects can now be re-sized and re-negotiated.

The Gulf monarchies have suffered from the opacity of their governance structures, particularly in the financial sector. International rating agencies still refuse to give the highest ranking to GCC sovereign debt due to fiscal and institutional nontransparency. Generally, however, the centralised state structures of the oil monarchies have allowed them to deal with the crisis swiftly. With the exception of Kuwait, authoritarian rule allows them to quickly push through adjustment policies, and the ubiquitous presence of the state in many markets makes smooth direct intervention possible without having to contend with politically sensitive nationalisation and private sector lobbying.

It was only in less well-financed Dubai that centralisation of power and opaque governance have led to deeper damage to the economic system through over-leveraging and a steep decline in international confidence. It is no coincidence that the country with arguably the strongest central bank with the most consistent track record, Saudi Arabia, has been least affected by the crisis.

Dubai’s strategy of hyper-globalisation is now seen with a very skeptical eye. GCC financial markets, real estate projects and FDI in general are likely to be more nationally and regionally focused in the coming years. The Gulf’s solid SOE structures will help the region to survive the crisis.

The global economic crisis does not pose a political challenge to the Gulf, and although it has created economic difficulties, most of the GCC states are well-equipped to handle them. The GCC countries will stay “globalised monarchies”, but will adjust their ambitions, in particular in the finance and real estate sectors. As in the West, the crisis has led to fiscal expansion rather than retrenchment, and most of the governments have sufficient resources to see their economies through several lean years.

[1] The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), also known as the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (CCASG), was created on 25 May 1981 and comprises the following six monarchies: Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.