Toward the Reformation of Islamic Finance: Southeast Asian Perspectives

By Clement M. Henry

The present collection of papers evolved from a workshop organized 16-17 February 2016 by the Middle East Institute for academics and practitioners to exchange insights about the development of Islamic finance in Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. Why the MEI engaged in such an undertaking perhaps deserves a word of explanation. While it was the Middle East, principally Egypt and the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), which launched the international experiment in interest-free banking in the 1960s and 1970s, it may well be that the core countries of Southeast Asia become the principal guarantors of its future.

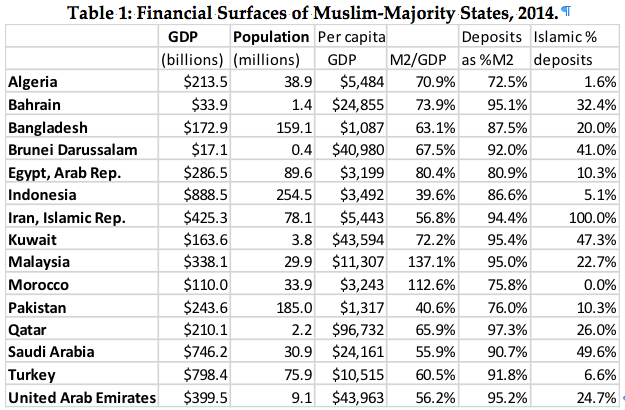

The numbers in the following table tell part of the story. Saudi Arabia, followed by the smaller GCC states of Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), have amassed the greatest market shares of Islamic bank deposits (along with Lilliputian Brunei), but potentials for future growth lie elsewhere. Whereas the

largest concentrations of Islamic financial assets are found among the relatively small and wealthy populations of the GCC, the biggest potential for Islamic banking lies in Indonesia, with its huge population including 220 million Muslims and, despite their relative poverty, a gross domestic product greater than that of any other Muslim majority country. Indonesia’s 19 million Islamic bank accounts probably outnumber those of any other country with the possible exception of Bangladesh, and they are just the tip of the iceberg as we shall later see.[1]

Malaysia is also of special interest, despite its relatively small population and middling GDP and per capita income, because it has engaged in greater financial deepening (M2/GDP), typical of more advanced economies, than any other Muslim majority country. Not only is its financial surface over 137 percent of its GDP. It also keeps 95 percent of its money supply inside the banking system rather than in fiduciary currency (cash stored at home or in one’s pocket). Malaysians seem to trust their banks. 80.4 percent of those age 15 and above have bank accounts, compared to only 69.4 percent of the Saudis.[2] Consequently, despite an economy less than half the size of Saudi Arabia’s, Malaysia has a larger money supply and an even greater deposit base than that of the Saudi banking system. While its Shariah-compliant market share was less than half that of Saudi Arabia in 2013, its total Islamic deposits and assets, already over half the latter’s, were likely to grow more rapidly. Malaysia’s Central Bank (Bank Negara Malaysia or BNM) projects an Islamic market share of 40 percent by 2020; by then its Shariah-compliant deposits might actually exceed Saudi Arabia’s.

Indeed, the other part of the story lies in Malaysia’s financial management and corporate governance. Malaysia has pioneered a national model of supervision and regulation of Islamic finance that accelerated its penetration of the conventional banking system. Brunei and Indonesia are emulating this model. Its deliberate institutionalization of Islamic finance from above contrasts sharply with the more ad hoc processes of monetary authorities in other countries.

One key difference lies in the very definition of an Islamic bank and who defines it. Writing in 2000, Ibrahim Warde left the responsibility to religious scholars. Any bank with a supervisory board of Shariah scholars’ became his working definition. But by this definition Dubai Islamic Bank, founded in 1975, would not have qualified until 1998, whereas some of Egypt’s rogue sharikat tawzif al-amwal (investment companies) might have qualified in the mid-1980s, when they were using religious scholars for public relations to cover their pyramid schemes. The semi-official association of Islamic banks based in Cairo at the time did not recognize the upstarts, but even today no official transnational instance has the authority to evaluate religious scholarship and the compliance of a bank with the Shariah. The Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB), established with help from the IMF to regulate Islamic financial institutions, “determines that appropriate Shar─½`ah compliance systems are in place;” in other words, this transnational authority merely supervises procedures. Islamic Financial Institutions are supposed to have a Shariah Supervisory Board (SSB) of at least three scholars. The banks and scholars are free to negotiate their relationships in much of the Middle East and Africa.

In Malaysia, by contrast, the BNM established a National Shariah Council to interpret Shariah and regulate the SSBs of individual Islamic banks and windows of conventional banks. This model is now attracting the attention of the monetary authorities of other states like Morocco that wish to avoid the ambiguities of conflicting interpretations of Shariah-compliant banking practices. In Indonesia, too, a National Shariah Board (NSB) consists “of the Islamic law experts (fuqaha’) as well as practitioners and economists, particularly in the financial sector, both banks and non-banks.”[3] As in Malaysia, the Shariah boards of individual banks must adhere to the interpretations adopted by the NSB.

The laisser-faire alternative practiced in much of the Arab world has encouraged an alternative market-oriented way of harmonizing interpretations of Shariah consonant with Islamic finance. The outcome of negotiations between banks and religious scholars reveals remarkable concentrations of scholars affiliated with the Shariah supervisory boards of the banks. Murat Ünal (2011) counted 20 top scholars occupying 621 board memberships as of December 31, 2010, while the remaining 260 scholars had only 520 positions in his data set, which included some 350 IFIs of Malaysia, Pakistan, the United Kingdom and the United States as well as most Arab countries. There was considerable overlap, too, between the top scholars serving on the boards of banks and those who set the global standards of Islamic finance in the IFSB, headquartered in Kuala Lumpur, and its sister Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) in Bahrain. Eight of the top 10 scholars also each held from three up to 12 positions in these and other standard setting institutions such as unions, foundations, government entities, and consulting firms.[4]

Each bank board included at least three scholars, and the top scholars tended to share their extensive networks with each other, further consolidating their hierarchy. At the apex of the scholarly hierarchy in 2010 Abdul Satar Abdul Karim Abu Ghuddah of Syria, Nizam Muhammad Yacoubi of Bahrain, and Muhammad Ali Elgari of Saudi Arabia occupied respectively 101, 95, and 86 positions in IFIs and standard setting bodies. Each had at least a 50-50 chance of serving with one another on any of their respective boards.[5] In fourth place, serving only 43 offices, but third in terms of his multitude of connections with other scholars, came a Malaysian, Muhammad Daud Bakar, despite the fact that scholars in his own country were prohibited from being members of SSBs of more than one IFI and its related Islamic businesses.[6] The top scholars served on boards of IFIs in many countries.

These transnational networks of scholarly authorities insured a certain harmonization of interpretative practices but raise questions about possible conflicts of interest. Indeed, in an earlier paper Walid Hegazy, one of our Workshop participants, compared the scholars to secular accountants. He observed that since the Enron scandal and the demise of the Arthur Anderson accounting firm, US legislation prohibits accountants from auditing firms for which they have also offered consultancy services. Shariah scholars, however, audit the banks as well as advising them on matters of Shariah. The Shariah scholars, moreover, are heavily involved in setting the standards of Islamic accountancy in AAOIFI as well as implementing them in the banks they serve.[7] The logic of their compromises among one another, or “shariah arbitrage,” leads to ever increasing convergence and between the practices of Islamic and conventional banks.[8]

The present set of papers examines the alternative Southeast Asian experiences of national control over the SSBs. Malaysia has progressed furthest in this direction and actively promotes Islamic finance, but Brunei and Indonesia have observed their neighbour and are following similar trajectories, at least up to a point. The issues to be discussed here are financial inclusion, Shariah governance, differing interpretations of Shariah-compliance with respect to bank investments (deposits) and sukuk (bonds), and conflicting approaches, in the final analysis, to accounting standards. The prospects of Islamic finance in the region and, more generally, of state centered development will then be discussed by way of a conclusion.

Financial Inclusion

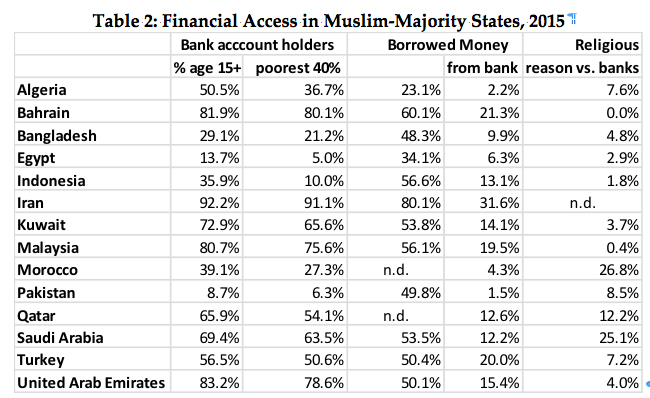

Table 1 indicates that Malaysia scores highest among Muslim majority countries in financial development. The proportion to GDP of its broad money supply held inside the banking system exceeds that of any other country reported in the table. By financial inclusion, however, is meant the proportion of a given population actually served by banks and other institutions such as post offices, cooperatives, and savings and loans associations. The World Bank’s Little Data Book on Financial Inclusion presents a variety of indicators, three of which are reported in Table 2.

Malaysia comes in third place, after Iran and Bahrain on a variety of indictors. Table 2 also reports that substantial percentages of some of these Muslim-majority populations, notably of Morocco and Saudi Arabia, cite religious reasons for not having bank accounts. While the question of whether Islamic finance really mobilizes greater financial inclusion went beyond the scope of the workshop, Dr. Ascarya, a senior research analyst of the Bank of Indonesia, presents his ideal vision of Islamic finance at work among Indonesians who may be too poor to access formal financial institutions. While few avoid banks for religious reasons, poor people seem to have little access to the formal banking system even though more than half of them borrow money from family, friends, or money lenders outside the formal banking system.

His paper presents the logic and values underlying an important Islamic financial institution outside the formal banking sector, the baitul maal wa tamwil (BMT). It is in his words “to empower the poor to step gradually from extreme poverty to some form of economic activity, eventually as an independent micro entrepreneur.” The BMT really consists of two “houses,” the baitul maal charity for the poor and the baitul tamwil financing arm for micro entrepreneurs. Zakat, waqf, and other “Islamic social tools” finance the former, whereas micro-savings and funding from other banks and other commercial sources serve the financing for prospective micro-entrepreneurs. Interviews with nine experts and nine practitioners indicated the underlying Islamic priorities to be the preservation of wealth, faith, intellect, and life, and the chief commercial objective to be financial sustainability. Dr. Ascarya also noted the dangers of “institutional mission drift,” observable in both conventional and Islamic banks, whereby “microfinance” is stretched to ever larger packages for economies of scale that reduce transaction costs.[9]

His vision is an integral part of the Indonesian Islamic Financial Market Development Framework presented for the workshop by Dr. Rifki Ismal (Appendix I). The Financial Services Authority (OJK) planned in 2016 to bring the country’s BMTs under its direct authority, even though the most prominent of them, some three hundred, were already under the supervision of the Ministry of Cooperatives. There were already reports of over 4000 BTMs in 2008 (CIMB 2016, 152), but they still constituted a very small percentage of Indonesia’s large sector of informal financial institutions involved in microfinance.

As Table 1 indicated, the market penetration of Islamic finance in 2014 reached a peak of some 5.1 percent of deposits held in the formal, regulated banking sector. It declined slightly in 2015. By 2016, however, some of the strategies advocated in Dr. Rifki’s Framework were already being implemented. In particular, President Joko Widodo took charge of a national Islamic finance committee (KNKS) proposed in Pillar 1 to regulate a concerted national effort from above, as in Malaysia, to give Islamic finance a second wind after its spontaneous expansion since 1992 by demand from below. Explicitly modelled on Malaysia’s International Islamic Finance Center, KNKS might not only coordinate such delicate matters as the regulation of the BMTs but also mobilize some of the funds of state enterprises and ministries for Islamic banks.[10] In particular, personal savings funds for the hajj could expand the Islamic finance share of the market. The comprehensive Framework does not provide specific targets. The Governor of the Bank of Indonesia projects modest growth, with the Islamic component reaching 6 to 8 percent in the coming five years “unless the structural problems remain unresolved,” whereas CIMB Islamic of Malaysia was projecting 11 to 13 percent. By contrast, Malaysia’s central bank was planning that Islamic banking in Malaysia occupy 40 percent of the market by 2020.

Shariah Governance

One of Indonesia’s possible “structural problems” in the eyes of bankers may be the cumbersome adaptation of shariah law to the business of banking. In his PowerPoint presentation Cecep Maskanul Hakim, Assistant Director of Indonesia’s Financial Services Authority (OJK), points to the complex procedures involving Shariah certification of new financial products (Appendix II). Before launching the new product, a bank must first seek approval first from its own SSB and then from the National Shariah Board consisting of some sixty Shariah scholars from Islamic financial institutions and the OJK. Its most active members join a working committee with representatives from the central bank and the Indonesian Accounting Association. The committee then recommends a fatwa to the National Shariah Board. Since its founding in 1999, the NSB has issued some hundred fatwas on such matters as the simple murabaha (instalment sales) and complex derivatives, such as hedging with foreign currency swaps.[11] The procedures for certification are so lengthy and subject to such a diversity of authorities, however, that Indonesia has so far managed to develop far fewer modern financial instruments than Malaysia. The grassroots of Shariah governance are the SSBs of the individual banks, whose members must be approved by the OJK. The regulatory authority’s “four pillars” or criteria for the functioning of these boards are competence, independence, discretion, and consistency in their rulings. In his presentation Hakim pointed to difficulties recertifying the SSBs of some 2000 financial cooperatives coming under OJK supervision.

As in Malaysia, to prevent conflicts of interest, scholars are restricted in the number of boards they may serve. One constraint, also alluded to by Rifki Ismal, is the difficulty of having Shariah scholars who also understand modern finance. With its more hierarchical approach managed by the BNM, Malaysia has developed new financial products more efficiently. Shamsher Mohamad and Zulkarnain Muhamad Sori present the formal structures and their corresponding functions of Shariah Risk Management Control, Shariah Review, Shariah Research, and Shariah Auditing. The BNM’s Shariah Advisory Council governs the SSBs of the individual financial institutions and ensures consistent shariah rulings. The authors argue that rulings are indeed consistent and the system prevents the “fatwa shopping” practices of some Middle Eastern countries, where service on many boards may also involve conflicts of interest. Based on interviews with 17 chairmen of Malaysian SSBs, however, they still note possible conflicts in their country. Bank managers

“are usually keen to fulfil their short-term key performance indicators’ to earn their targeted remunerations. Furthermore, the Shariah committee members usually receive remuneration from the IFIs which could lead to legitimizing unlawful or dubious operations, products and services because of the monetary incentive.”

Consequently the unregulated pay scales of Malaysian Shariah scholars, notably of expensive foreigners, may still lead to some conflicts of interest. The authors also cite a report of the International Shariah Research Academy (established by the BNM in 2008) that “more than 54% of fatwas issued between Malaysia and the GCC are in direct conflict with each other.” Many Malaysian sukuk, for instance, are not recognized in the GCC as being Shariah-compliant, an important point to be further discussed below.

Possibly the very success of the BNM in promoting Islamic finance has sacrificed its credibility. Rosana Gulzar Mohd presents a brilliant challenge, asking whether the German financial system, with its cooperatives and savings and loans Sparkassen, is not more truly in the spirit of Islam than Malaysian Islamic banks, which so effectively compete against conventional banks by mirroring them. She also observes that the Sparkassen originally inspired Dr. Ahmad Najjar, the early Egyptian pioneer of Islamic finance in rural villages north of Cairo. Her critique is designed to be constructive and suggests ways in which Islamic finance may regain its credibility through greater public control and regulation of key financial sectors and less reliance on greedy private financiers. She also recognizes that the BNM “made a laudable attempt to right the ship” in 2013, in a Financial Services Act that included a provision for investment accounts designed to reflect profit and loss sharing in addition to regular demand deposits and savings accounts.

Bank Deposits and Investment Accounts

Until recently, mandatory deposit insurance covered the deposits of all licensed banks, Islamic as well as conventional, in both Indonesia and Malaysia, despite the risk sharing ethos of Islamic finance. The issue of whether deposit insurance should cover deposits in Islamic banks was under discussion in 2015 in Indonesia but without any definitive rulings as yet by the National Shariah Board. In Malaysia, however, as Rodney Wilson explains, the new investment accounts were intended to reflect the Islamic prescription of risk sharing although in practice any investment losses are also to be covered by the Malaysia Deposit Insurance Corporation (PIDM). The Malaysian authorities argue that the investor and the Islamic bank are still sharing risk since it is a third party, the PIDM, which protects the investor from losses.

In his detailed analysis of the banks’ treatments of these new investment accounts, Saiful Azhar Rosly also shows that the investors do not receive profits commensurate with those received by those who really do share profits and losses, namely the shareholders of the banks. Consequently these investment accounts do not really reflect the Islamic ethos of profit and loss sharing that had originally inspired them. In his words “Such discrepancy in performance of deposit funds and capital funds may trigger Shariah non-compliance risk.” Profits tend to mirror those of conventional banks’ interest revenues, and the principal is protected like that of an ordinary bank deposit.

Sukuk Financing

As noted above, there are sharp divisions of opinion concerning Shariah-compliant sukuk. Walid Hegazy, who has extensive experience with legal practices in the GCC, insists that they must be backed by a real asset or contractual arrangement concerning its use, such as an infrastructure project. An analogy in conventional security markets might be preferred stock with fixed dividends. Many sukuk, however, are asset-based rather than asset-backed and consequently more closely resemble conventional long term debt than equity. The principal is usually guaranteed, whereas an asset-backed sukuk may lose value. Tahir Ali Sheikh, in charge of Islamic Banking Asset Management & Investments for Malaysia’s CIMB Islamic Bank, presents the same definition in his PowerPoints (Appendix III) as Hegazy, but most Malaysian sukuk are asset based, with the principal being guaranteed.

Hegazy observes an interesting correlation between sukuk issues with oil prices and shows new issues undergoing a sharp decline in 2014 and 2015. He also notes that most GCC countries will probably follow Saudi Arabia in relying more on conventional bond issues than on sukuk to meet their financial shortfalls caused by diminishing oil revenues. By contrast, Sheikh raises prospects of greater sukuk issues to meet Asia’s infrastructural needs, if given the appropriate legal frameworks. He also observes Indonesia “to be the most prolific sovereign sukuk issuer to date.” Malaysia, however, offers the friendliest environment for business enterprises to raise funds by issuing sukuk because of the government’s “tax neutrality,” “cost neutrality,” and favourable legislation; in fact, sukuk issues usually exceed those of conventional bond issues each year (Appendix III, 25-27). The majority of the world’s outstanding sukuk (which total over US$300 billion) have been issued in Malaysia, for the most part in local currency.

Accounting Standards

Arcane issues of accounting turn out to illustrate some of the differences between the Malaysian and other approaches to Islamic finance already emerging in the segmentation of sukuk markets. While visiting Brunei, the editor of these workshop papers met Denny Hanafi, whom the sultanate’s leading Islamic bank had commissioned immediately in 2015 to convert to the new International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), following Malaysia’s lead. In Brunei, the orders came from the Sultan, who is also finance minister, while his son heads the Monetary Authority of Brunei Darussalam (AMBD). For a snapshot of Brunei’s financial system see Appendix IV. The task of converting the bank’s accounting system would be time consuming. At issue is how to account for profits and losses in various financing contracts between Islamic banks and their customers.

In Appendix V Denny Hanafy illustrates the differences in a simple instalment sales agreement between the standard accounting practices prescribed by the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) and IFRS. The Islamic “profit rate” of 7 percent is the precise equivalent of an effective interest rate of 10.916 percent in his example of a five year financing of a sale with an initial cost of US$100,000. Whereas the 7 percent profits are recognized each year under AAOIFI rules, the identical annual repayment schedule of US$27,000 results under IFRS in significantly higher financial profits, with important consequences for the income statements and balance sheets of the financial institution and possibly also for the performance evaluations of bank managers.

Rosman et al spell out the characteristics of Hanafi’s exemplary murabaha and compare the treatment of its profit rates with the interest rates of conventional instalment sales or mortgages. They carefully explain how Shariah scholars may view the discounting techniques required by IFRS to be in conflict with the Shariah-compliant prescriptions of AAOIFI. In Malaysia, however, the BNM has accepted an analysis of ISRA that distinguishes between mathematical techniques for recording transactions, which may involve discount rates, and the actual transaction generating profits, not interest. “The application of the time value of money is permissible only for exchange contracts that involve deferred payment and is strictly prohibited in loan transactions.” It is acceptable if the economic substance of the contract is for financing rather than trading. The authors carefully compare the IFRS accountant treatment illustrated by major Malaysian Islamic banks with the AAOIFI procedures illustrated by a major Bahrain bank. They note “cases which reveal the inadequacy of IFRS in catering to the unique characteristic of Islamic financial transactions” and judiciously conclude “In the case of the murabaha contract, the financial reporting objectives can be achieved by disclosing greater information in the notes accompanying the financial statements.”

Dodik Siswantoro pursues a parallel line of inquiry about Indonesia’s efforts to engage with IFRS in the treatment of sukuk. He compares Indonesia’s efforts with those of Malaysia and closely examines the revision of its Statement of Financial Accounting Standard (SFAS) 110 in 2015 to accommodate IFRS. The process of revision was a lengthy one, involving public hearings as well as extensive consultations between bank managers, accountants, regulators, and Shariah scholars.

Clearly Indonesia is “stricter” than Malaysia in its interpretation of Shariah because its scholars reject the use of discount and interest rates for the valuation of sukuk.[12] The scholarly consensus in Indonesia seems to reject the Malaysian distinction between charging interest and recording the substance of a transaction as if it were interest-based. “Riba (usury) concerns not only the person who is charging interest but also the one who records the interest rate transaction,” argued one of Siswantoro’s sources.

In practice some Indonesian Islamic banks were ready to apply IFRS and initially objected that the revision of SFAS 110 did not go far enough. Siswantoro shows, however, how the balance sheets and income statements of six leading banks were gradually being brought in line with Indonesia’s new compromise standard.

Regional Prospects

To date, the oil-rich GCC countries have driven the demand for Islamic finance since the oil shocks of the 1970s. Wealthy Gulf investors diversified their portfolios and seemed eager not only to place some of their funds in “Islamic” banks but also to invest in Shariah-compliant securities, such as sukuk with fixed rates of return. With declining oil prices and increasing debt in the GCC, however, the concerned governments seem to be turning more to conventional bonds than to more problematic sukuk. The question now is whether the novel enterprises of Islamic banking and capital markets will gain traction among the growing masses of Muslims who are engaging in financial activity. Southeast Asia, with its proximity to expanding Far East markets, is the key testing ground. Building on the Malaysian experience, it may also be a proving ground for sukuk financing of major infrastructure projects.

Whether with respect to accounting standards or Shariah-compliance, differences remain between Indonesia, on the one hand, and Brunei and Malaysia on the other. The potential giant of Islamic finance takes slow, deliberate steps towards increasing the market share of Shariah-compliant products and seems attentive to scholars who might otherwise issue warnings of “Shariah non-compliance risk.” Consequently it does not emulate conventional banking techniques as rapidly as the more efficient Malaysian system.

The workshop concluded the discussion of the region’s prospects by proposing greater interchanges between the four Southeast Asian countries in efforts to develop common standards (see Appendix VI). Daud Vicary, the CEO of INCEIF, suggested STARS, a five-point review of how each set of country actors could learn from one another about Shariah, taxation, accounting, regulating, and standards. Despite the infinitesimal share of Singapore’s Islamic finance market, this international centre, too plays a significant regional role. As Zubir Abdullah, an official of the Monetary Authority of Singapore, explained to the workshop,

Singapore’s role in the Islamic financial industry is to complement and not to compete with Malaysia and Indonesia. Singapore’s approach is to regulate Islamic finance under one common regulatory framework. After discussions with other jurisdictions, theMonetary Authority of Singapore is of the opinion that apart from Shariah, the prudential and regulatory considerations for regulating Islamic financial entities are the same as conventional entities. Since Singapore is a secular country, it has taken a similar approach to the United Kingdom. Hence it is the onus of financial players involved in Islamic finance to strengthen their corporate governance in respect to Islamic finance transactions.

By utilizing a common framework, we do not have a separate framework to regulate Shariah or provide separate licenses for Islamic banks. The Islamic Bank of Asia was regulated under the same framework as any bank. This also means that once MAS has approved a license, the institutions have the option of conducting conventional and/or Islamic transactions. That is why there seems to be an anomaly, where you don’t see Islamic finance institutions in Singapore. However, it is actually growing because they are connected by windows.

Regional financial integration, an ongoing ASEAN process, may facilitate greater interaction and competition among Islamic as well as conventional banks. While the Indonesian authorities have delayed the formation of an Islamic Megabank to meet the competition from Malaysia’s larger banks,[13] they are slowly coordinating the efforts of various ministries, state enterprises, professional associations, and regulatory authorities.

Perhaps, as Rosana Gulzar Mohd suggests in her paper, the prospects of Islamic finance hinge on larger societal developments. Indonesian democracy in particular may lead the way in adapting Islamic finance to the exigencies of the modern world. While new product development is slower and less efficient than that of Malaysia, it rests on more secure foundations of consensus reached by the scholarly community with bankers, regulatory authorities, and business professionals.

Clement Henry, who wrote until 1995 under the name of Clement Henry Moore, has conducted research on political parties, the engineering profession, and financial institutions in various parts of the Middle East and North Africa since 1960. Before coming to Singapore in November 2014 he was chair of the Department of Political Science at the American University in Cairo, after having retired from the University of Texas at Austin in 2011. Earlier he had directed the Business School at the American University of Beirut, taught at the University of California, both at Berkeley and Los Angeles, at the University of Michigan, and at the Institut d’Etudes Politiques in Paris. He is currently studying Islamic finance, following up on his Politics of Islamic Finance (2004), co-edited with Rodney Wilson, and is also working with Robert Springborg on a third edition of their Globalization and the politics of development in the Middle East (2001, 2010). He has also tried to trace the career patterns and politics of a cross section of Algeria’s retired political elite, drawn from interviews with student leaders whom he interviewed in 1955-1962: T├®moignages (2010, 2012). Recently he co-edited The Arab Spring: Will It Lead to Democratic Transitions? (2013). Clement Henry received his PhD in political science from Harvard University and an MBA from the University of Michigan.

References

CIMB Islamic. Indonesia Islamic Finance Report: Prospects for Exponential Growth, Thomson-Reuters, 2016. http://www.irti.org/English/News/Documents/421.pdf

Robert W. Hefner. Islamizing Capitalism: On the Founding of Indonesia’s First Islamic Bank, in Arskal Salim and Azyumardi Azra, eds., Shari’a Politics in Modern Indonesia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, National University of Singapore, 2003, 149-167.

Clement M. Henry. Islamic Finance in Indonesia: High Tide or New Mecca?, Middle East Perspectives Series 5, Middle East Institute, National University of Singapore, 15 August 2015. https://mei.nus.edu.sg/index.php/web/publications_TMPL/islamic-finance-in-indonesia-high-tide-or-new-mecca

Rifki Ismal. Islamic Banking in Indonesia: Lessons Learned, Multi-Year Expert Meeting on Services, Development, and Trade: The Regulatory and Institutional Dimension, UNCTAD, Geneva, 6-8 April 2011. http://unctad.org/sections/wcmu/docs/cImem3_3rd_S4_Ismal.pdf

Murat ├£nal. The Small World of Islamic Finance: Shariah Scholars and Governance ÔÇô A Network Analytic Perspective, v.6.0 (18 January 2011), Funds@Work: http://www.funds-at-work.com/uploads/media/Shariah-Network_by_Funds_at_Work_AG.pdf.pdf

Angelo M. Venardos. Islamic Banking and Finance in Southeast Asia: Its Development and Future, Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company, 2012.

[1] The only possible competitors indicated in Table 1 are Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. The World Bank’s Little Data Book on Financial Inclusion indicates that the 69.4, 13.0, and 31.0 percent of their respective adult (15+) populations (of 20.5, 120.5, and 109.6 million) had bank accounts in 2014, compared to 36.1 percent of 177.7 million adult Indonesians. Microfinance seemed as prevalent in Bangladesh as in Indonesia, and the country’s greater Islamic share of deposits perhaps compensate for the smaller total population.

[2] World Bank, 2015 The Little Data Book on Financial Inclusion, Financial Inclusion Database.

[3] National Shariah Board, Indonesian Council of Ulama, Fatwa, published in cooperation with the Central Bank of Indonesia, 2012, p. iv.

[4] Murat ├£nal, The Small World of Islamic Finance: Shariah Scholars and Governance ÔÇô A Network Analytic Perspective, v.6.0 (18 January 2011), Funds@Work, p. 4.

[5] Ibid., pp. 5, 8, 10, 22-23.

[6] Ibid., pp. 5-6.

[7] Walid Hegazy, Fatwas and the Fate of Islamic Finance, in S. Nazim Ali, ed., Islamic Finance: Current Legal and Regulatory Issues, Islamic Finance Project, Harvard University, 2005, pp. 139-141

[8] Mahmoud A. El-Gamal, Limits and Dangers of Shari’a Arbitrage, in S. Nazim Ali, op.cit., pp. 117-132, http://www.ruf.rice.edu/~elgamal/files/Arbitrage.pdf

[9] The Indonesian Financial Services Authority (OJK) defines the upper limit of a microfinance loan to be DR 50 million (less than $4000 in 2016).

[10] Rifki Ismal (2011, 10) observed that ten percent of the available financial assets of state enterprises together with the hajj funds stored in conventional banks could have almost tripled the asset base of Islamic banks in 2010.

[11] For more about the NSB see Hefner (2003) and Henry (2015). For useful background on the evolution of Islamic finance in Indonesia, see Angelo M. Venardos (2013, 138-150).

[12] Siswantoro also points to another example, the bay al innah'” permissible in Malaysia but not in Indonesia. This is because that scheme contains two transactions in one contract, which is prohibited in Indonesia. In practice, it is like a loan in a sale-and-buy-back that does not really occur.

[13] The proposed “megabank” would be the result of combining the Islamic financing arms of four state-owned banks: PT Bank Rakyat Indonesia, PT Bank Mandiri, PT Bank Negara Indonesia, and PT Bank Tabungan Negara.