German Banks: More Islamic Than Islamic Banks?

By Rosana Gulzar Mohd

“Islamic banking, in its current form, will go down in history as a mighty deceit based on an operational principle that is simply unfeasible. Islamic banks give and take interest as a matter of course, though under the guise of commissions, fees, penalties or profit shares. The holder of a “halal” credit card pays a penalty on unpaid balances; this penalty is proportionate to the size of the balance, which makes it equivalent to interest.”

Timur Kuran in a 2013 Financial Times interview[1]

While this is an accurate description of Islamic banking currently, where Kuran is wrong however, is in his assertion that the fault lies with the Shariah. That they are unsuitable for current times. This paper argues that genuine Islamic banking is possible when there is an ecology of institutions and people who embrace the precise values that drive this form of finance. The malaise that afflicts Islamic banking currently is brought on by an unthinking submission to the free market objectives of profit-maximisation at the expense of justice, equity and social welfare.

Malaysia is a classic case in point. Its latest scandal, involving the country’s multi-billion-dollar pilgrims’ fund, Tabung Haji (TH),[2] belies deep fractures in the financial system. The issue is not only in the state of its Islamic finance. It goes further into whether the country has an economic system that is conducive to Islamic finance. Malaysia is at an interesting crossroad that may offer its people a chance of redemption or at least a change. Rocked by a political turmoil that has spilled into the economy, the calls for a new prime minister are getting louder, just as its long-serving governor of the central bank vacated the seat for her successor.

Under the patronage of Zeti Akhtar Aziz, the recently retired governor, Islamic finance’s market share has grown to 26.8 percent of domestic banking assets[3]. Maybank, the country’s largest, said that it disbursed more Islamic than conventional financing for the first time in 2015.[4] A look beyond the numbers however, gives cause for worry. Islamic finance has been accused of being no different from conventional finance although their founding theories are diametrically apart.[5] In theory, its ban on interest or riba calls for earnings that can only be justified through work, ownership or liability. By extension, the prohibition encourages a spirit of mutuality in helping one another shoulder burdens and share rewards. In practice, however, Islamic finance in Malaysia embodies more of the profit-maximisation, risk-transfer characteristic of riba-based conventional banking.[6]

Recognising this conundrum, Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM), its central bank, has made a laudable attempt to right the ship. As part of the Islamic Financial Services Act (IFSA) 2013, it requires Islamic banks to make a clear distinction between deposits and investments. The former are principally guaranteed while investors, in the spirit of profit and loss sharing in Islam, need to accept market-based returns, even if that means a loss. Islamic banks are not surprisingly resisting these efforts, citing their incompatibility with current financing and legal systems.[7].

Bankers say there are still limited options for Shariah-compliant investments, both short- and long-term. And customers, including Muslims, are accustomed to deposit guarantees and fixed returns. How then do banks suddenly sell them an investment account’ that promises neither? Most importantly, how does the dual system in Malaysia handle different rates of return for conventional and Islamic banks? Does BNM have a plan for the ensuing capital flight? These factors have led Islamic banks in Malaysia to do more, not less commodity murabaha, the contract known to offer riba through the backdoor.

BNM said in its 2015 Financial Stability and Payment Systems Report’, “On the liability side, Islamic banks issued more fixed rate funding instruments such as tawarruq (fixed rate deposits) with longer contractual maturities to narrow the re-pricing gap against Islamic banks’ fixed rate assets. As at end-2015, fixed rate deposits of Islamic banks increased to account for a significantly higher share of 56.8 percent (2014: 35.7 percent) of total deposits, or 42.7 percent (2014: 30 percent) of the total funding base.”

It continues, “The shift towards tawarruq was also partly in response to the regulatory requirement to clearly differentiate between deposit and investment account products in accordance with the IFSA 2013. This increased demand for deposit products that are principal-guaranteed. In contrast, mudarabah-based general and specific investment deposits declined by 84 percent to account for 3.1 percent (2014: 19.7 percent) of the funding base.” [8]

The reason for this failure is that the policy makers, in drafting IFSA 2013, seem to not have borne in mind the bigger economic setting in which their Islamic finance industry fits. As mentioned, for Islamic finance to flourish, it needs an ecology of people and institutions who are sympathetic to its higher ideals of social welfare and justice. The current reform effort can thus be likened to squeezing a square peg into a round hole. They just do not fit.

Comparing the Malaysian System Against Germany

This study thus sets out to compare the Malaysian system against another system which seems better at upholding the Shariah principles. Germany is an interesting case study because besides having a World Cup champion football team, the country also ranks highly for economic development, financial inclusion, funding for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and the provision of state welfare without losing competitiveness.[9] There could thus be much to learn from such a society.

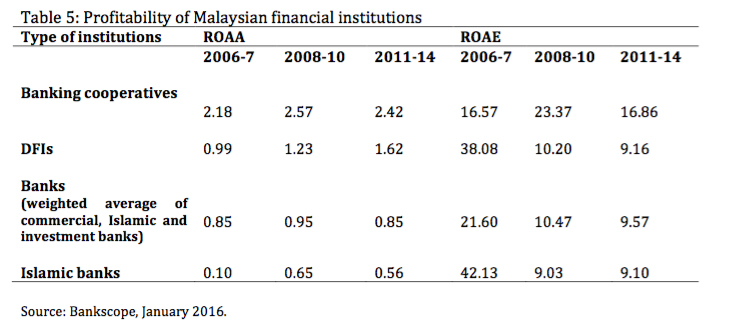

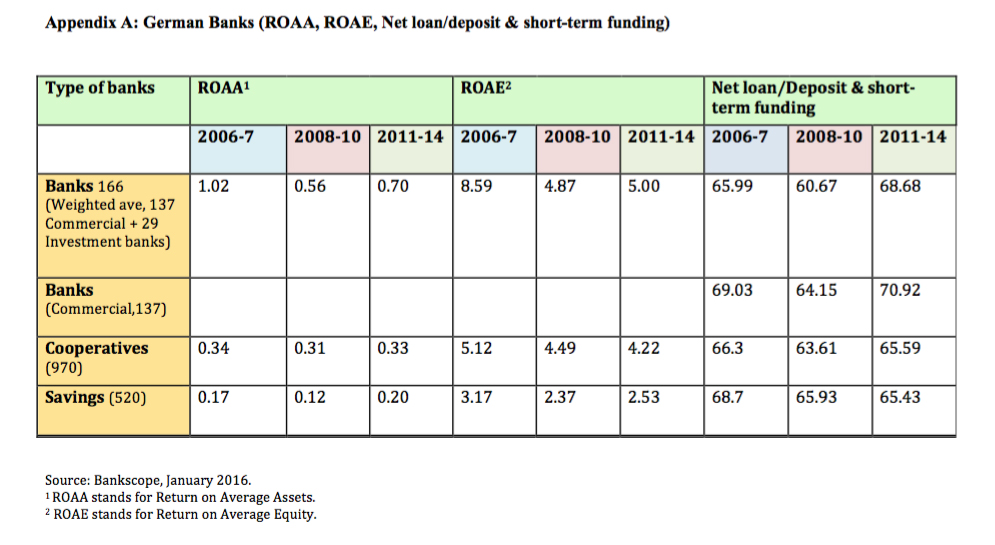

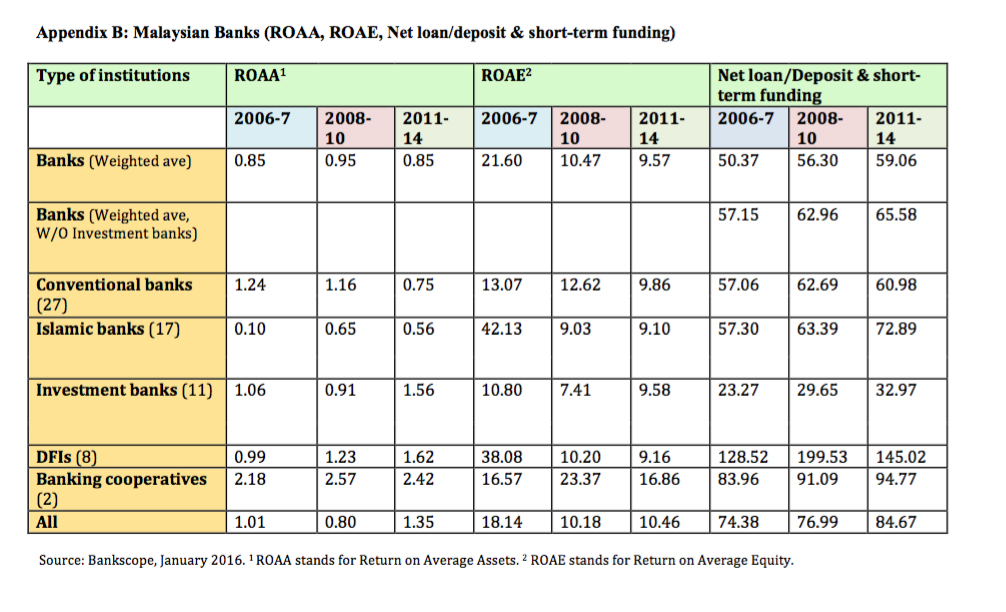

Specifically, this study compares the profitability and stability of banks in both countries between 2006 and 2014. This covers their performances before, during and after the global financial crisis. The profitability and stability are measured through the banks’ returns on average equity (ROAE), returns on average assets (ROAA) and net loan to deposit and short-term funding. ROAE, which is net income/average shareholder’s equity, reflects the banks’ ability to generate profits out of shareholders’ monies. ROAA, on the other hand, measures net income/average total assets. It shows the management’s efficiency in using assets to generate earnings. The stability indicator, net loan to deposit and short-term funding, is a proxy for Basel’s Net Stable Funding Ratio, which measures the proportion of long-term assets funded by long-term, stable funding.[10]

Although it focuses on the Islamicness of Islamic banks, the present analysis extends to conventional banks and interest-bearing institutions in Malaysia because as mentioned, the form of Islamic finance currently is in essence, conventional finance. Thus, even if the country achieves its 2020 goal of a 40 percent market share, or becomes 100 percent Islamic’, the system remains at heart, conventional. Another reason why the analysis includes other institutions such as conventional banks, development financial institutions (DFIs) and cooperatives is that, as mentioned also, in righting the ship for Islamic finance, one needs to bear in mind the broader economic setting and the Islamic banks’ interactions with other institutions. Islamic finance does not exist in a vacuum, so correcting it will likely require changes in the overall system as well.

Germany’s Unique System

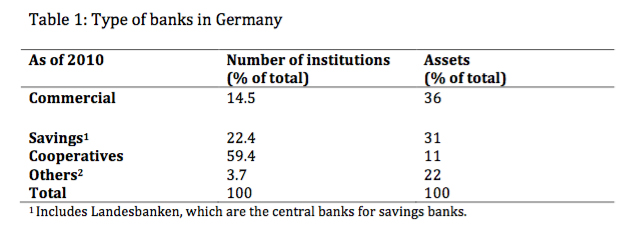

Germany is chosen because of its unique financial landscape, which is made up of “three pillars”. While it has private, commercial banks, the system is dominated by state-owned savings banks, or Sparkassen in German, and community-owned cooperative banks. Together, they contribute almost half of the financial system’s assets.

Given the objective of drawing lessons for a system conducive to Islamic finance, this paper focuses on the latter two types namely, the savings and cooperative banks. In Germany, there are 439 savings banks and 1,140 cooperative banks,[11] which contribute almost half of the financial system’s assets. The rest mainly comes from the three private banks there. The savings banks, which are owned by local governments, are not required to maximize profits although they need to avoid making losses. This allows them to pursue other goals such as supporting local cultural, social and economic development. The cooperative banks have a similar mandate but they are owned by their members who, in turn tend to be their depositors and borrowers. The cooperative banks operate a mutual guarantee scheme and their key role is to support the economic undertakings of their members, who represent about half of their customers. Essentially, both the savings and cooperative banks are geared to provide financial services to the German public and SMEs.

Germany presents an interesting case study for Islamic finance because its long history of savings and cooperative banks shows how the society has embodied the Shariah principles of pooling resources for a greater, common good as in the case of takaful. These two types of banks also show how the country has embraced the mutual sharing of profits and losses, a key requisite of the musharakah contract in Islamic finance. Their success seems to be due to the fact that the savings and cooperative banks are under less pressure to maximise profits compared to commercial banks because the shareholders are the state or the communities themselves. This allows them to focus on due diligence to spot sustainable businesses for financing, after which they will partner the companies over the long haul. These features have not only helped the less credit-worthy members of their society gain financing but has also made the German financial system more stable.[12] In fact, a 2010 study by S. Rehman and Askari found that the German economy is more Islamic than Malaysia. In their Economic IslamicityIndex’, Germany is ranked 26 while Malaysia came in at number 33, the highest for a Muslim majority country.[13]

Indeed the founder of the world’s first Islamic bank, Ahmed El-Najjar, was impressed with how the German savings banks aided the economic recovery of West Germany after World War II. In 1963, he set up Mit Ghamr local savings bank in Egypt by combining the German savings banks’ way of inculcating thrift with the village people’s deep religiosity. Most significantly, El-Najjar’s bank showed how we can foster a responsible financial attitude among customers, something grossly lacking in today’s consumeristic and debt-laden world. Specifically, the way his bank linked investment financing to the investment accounts may offer lessons for the architects of Islamic finance reform. El-Najjar used profit-sharing contracts such as mudaraba and musharakah for the investment accounts, the monies of which could only be withdrawn after a year. The returns would be commensurate with the size of the deposit and the bank’s profits. Another incentive for investors was their access to investment loans.[14]

Even the way the loans were disbursed offers lessons. They went exclusively towards the setting up of small businesses in the area. When investors showed promise but lacked the initiative to secure financing, the bank’s staffs would help. For one such customer, the bank built a factory and gradually transferred ownership to him. Mayer, A. E. (1985) cited someone who observed the project, R K Ready, as saying that the villagers were deeply grateful for the critical financing, which they believed would not have come from other sources. El-Najjar’s model was, however, short-lived due to a dispute with the Egyptian government.[15]

Another renowned academician, Mahmoud el-Gamal, argues that the concept of mutuality, as exemplified by the German Sparkassen and cooperative banks, can bring contemporary, erroneous practices of Islamic finance back to its roots. It simultaneously addresses corporate governance as well as religious concerns.[16] The former is an issue, especially for investment accounts, because their owners lack protection both internally through board representation or externally through market discipline.

The religious concern that mutualisation can ameliorate is ironically the prohibition of riba. As El-Gamal argues, Islamic banks currently avoid the formal prohibition in a money-for-money transaction by turning it into a money-for-property transaction (in murabaha financing) or money-for-usufruct transaction (in ijara financing). But high levels of interest, or profit, as Islamic banks call it, can still occur since there are no legal ceilings on profits in sales. Add to that the profit-maximisation drive of current Islamic banks and borrowers will most likely end up with the highest interest rates possible as depositors get paid the lowest. Mutualisation, by aligning the interests of investment account holders with the banks’ shareholders, ameliorates the current warped incentive structure where managers prioritise the interests of shareholders by maximising profits at the expense of customers on both sides of the balance sheet.

Issues with Malaysia’s Islamic Finance

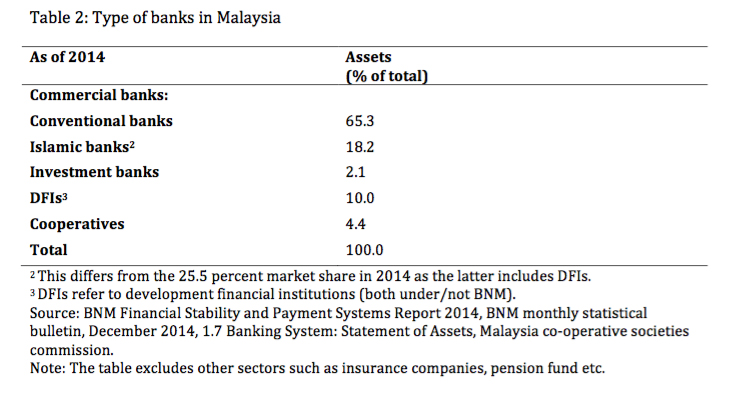

Malaysia has parallels to the German system. It has two groups of financial institutions: one falls under BNM and the other is supervised by various government ministries. BNM supervises the commercial banks (Islamic and conventional), investment banks and six DFIs. The rest, made up of non-bank financial institutions such as cooperatives,[17] other DFIs and a building society, are supervised by the government ministries.

Like Germany, Malaysia has commercial banks, state-backed development banks and cooperatives but unlike Germany, the commercial banks dominate the system in terms of assets. They are the largest providers of funds in the banking system, as reflected in the first four rows of the table below.

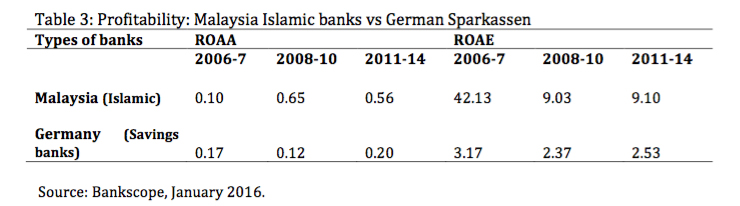

Herein lies the issue with the way Malaysia has built its Islamic finance practice. Like most countries in the world today, Malaysia adopts a mixed economic system where free market principles intersperse with a degree of economic planning and state-directed activities.[18] Largely a reflection of the free market principles, its banking system is dominated by commercial banks. This creates a problem for Islamic banks because they are made to compete head-on with other commercial banks in a profit-maximising arena when they are based on diametrically opposite founding theories of a prohibition of interest and, therefore, non-profit maximisation. Indeed Bankscope data confirmed the hypothesis that Malaysian Islamic banks are significantly more profitable and more efficient at using assets to generate income compared to German savings banks (Table 3).[19] The trend largely holds except for a blip in ROAA in the pre-crisis years.

This race for profitability belies a dire issue. In order to survive, the Islamic banks have had to quickly adopt contracts that mirror their conventional counterparts. This led to an adherence of the interest prohibition in form, but not spirit[20]. Likewise, the Islamic banks have compromised on their social obligations in exchange for maximum profits[21]. Another casualty seems to be the system’s stability. Although the German savings banks are less profitable than the Malaysian Islamic banks, their recovery post-crisis was stronger. The German savings banks enjoyed an ROAE rebound of 6.75 percent[22] compared to the 0.78 percent[23] improvement for Islamic banks. Further, the formers’ ROAA jumped 66.7 percent post crisis compared to a decline of 13.8 percent for Islamic banks. These results affirm Ahmed El-Najjar’s observations of the German savings banks’ tenacity in riding out a crisis while supporting the notion that Islamic banks in Malaysia, in their drive for profit-maximisation, are as unstable as their conventional counterparts.

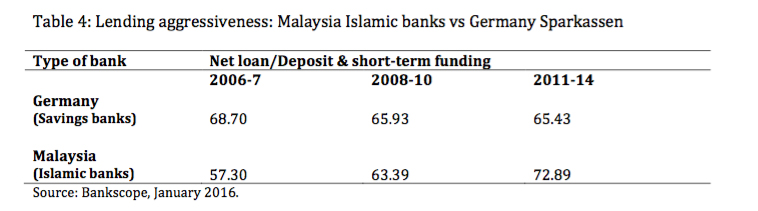

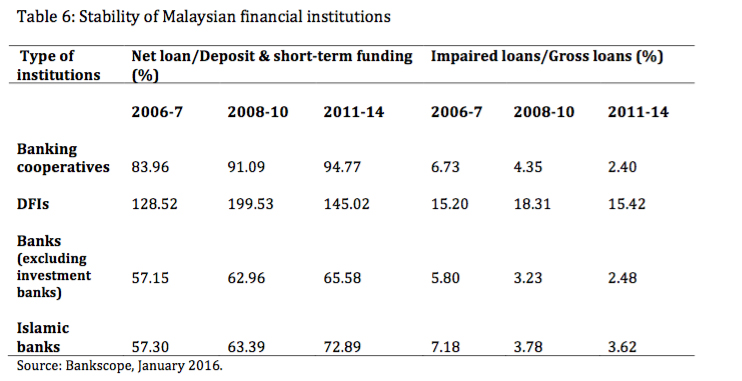

In terms of their lending aggressiveness too, an interesting trend unfolds when Malaysian Islamic banks are compared against the German savings banks. The former are getting more aggressive post-crisis compared to German savings banks (Table 4). Before the crisis, their net loan to deposit and short-term funding ratio was lower than the German savings banks. This ratio became comparable during the crisis and continued northwards in recent post-crisis years. This may be due to the government’s concerted effort to increase the market share of Islamic finance to 40 percent by 2020.[24]

This fixation of registering ever higher numbers, however, may have worrying implications. The most obvious is the higher liquidity and default risks that Islamic banks are piling on with an increasing loan-to-deposit ratio. The urgency to grow has also led to a focus of form over substance. While the German savings banks are known for inculcating thrift and riding out crises, Islamic banks in Malaysia are accused of using shariah-compliant’ contracts which are not anchored on Islamic principles of justice and equity. Contracts used for home financing such as bai bithman ajil or BBA and more recently, murabahah, musharakah and ijarah have left customers with most of the risks and Islamic banks most of the profits.[25]

In one landmark ruling in 2006, the judge of a local, civil court said in a case involving a home financing default[26] that a borrower under a riba loan would have paid less interest than a purchaser under the Islamic’ facility.[27] The High Court then reduced the amount sought by the bank from the home buyer by RM 376,000. BNM later avoided future embarrassing judgments by mandating its Shariah Advisory Council as the ultimate decision maker on cases involving the Shariah-compliantness of its Islamic banks.[28]

The 2020 goal also means the country has less than four years to garner an additional 15 percent market share when it has taken over 30 years to reach the current 26.8 percent. In short, as long as the Islamic banks in Malaysia are made to compete head-on with conventional banks in the private sector, we may fall short, quantity-wise, of the 40 percent target market share, not to mention, the apparent disconnect, in terms of quality, between their profit-maximisation drive and the Islamic values that the banks are supposed to embody.

Malaysian DFIs and Cooperatives

Another issue with the Malaysian financial system is that while it has community-oriented’ financial institutions such as the DFIs and cooperatives, they are dwarfed in asset size.[29] Additionally, since the 1970s, they have been beleaguered with allegations of misconduct of senior executives, fund misappropriations and even predatory lending tactics.[30] So although the DFIs and cooperatives have the largest potential to uplift the economic well-being of Malaysian society, especially the lower-income groups, they have had the opposite effect in Malaysia. The country’s level of financial inclusion, while higher than its benchmark group of countries, shows a 5-7 percent disparity between all adults and the poorest 40 percent and those living in rural areas. Similarly, while Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) form almost all types of enterprise in Malaysia, they only contribute to a third of the GDP.

Comparable, if Not Higher, ROAE and ROAA than Commercial Banks

Indeed Bankscope findings on Malaysia’s DFIs and cooperatives are startling. Firstly, in terms of profitability, both the ROAE and ROAA for DFIs and banking cooperatives are comparable, if not higher, than commercial banks (Table 5).[31]

That the DFIs and banking cooperatives are more profitable than the commercial banks, even the Islamic banks, are unexpected as the former two institutions are supposed to focus on financial inclusion at the expense of higher profits. Indeed, German cooperatives and savings banks have lower ROAEs and ROAAs than their commercial and investment banks.

DFIs and Banking Cooperatives are Alarmingly Aggressive in their Lending

The second surprise was in the lending aggressiveness of the DFIs and banking cooperatives. While the commercial banks seem prudent in their lending using short-term funds, these two institutions are alarmingly aggressive (Table 6). During the crisis, DFIs increased their proportions of net loans using short-term funding by 55 percent when other types of banks increased theirs by 8.5 to 10 percent.

To an extent, this is understandable as the crisis and post-crisis period was one of deleveraging for banks. As leverage shifted from the private to public sector, public institutions such as DFIs and cooperatives stepped in to provide finance while banks retrenched. However, the extent of lending aggressiveness in these institutions is still alarming. In comparison, a study of credit unions worldwide, a particular type of cooperative, showed loan to deposit ratios which on average, is well below unity.[32] Given that the Malaysian DFIs and banking cooperatives also have higher percentages of impaired loans compared to commercial banks, these suggest that the Malaysian financial system is less stable than Germany not because of the profit-driven commercial banks but because of its DFIs and cooperatives.

This is surprising because the presence of these latter two institutions tend to add, not reduce stability. On the other hand, profit-driven commercial banks tend to be blamed for bringing the house’ down with their risky practices and reckless trading positions. In Malaysia, it seems to be the other way round.

Issues with the DFIs and Cooperatives

Indeed the DFIs and cooperatives in Malaysia suffer from a number of issues, namely their aggressive lending and a lack of protection for depositors. To be fair, these institutions constitute a small part of the banking system or 14.4 percent of assets, to be exact (Table 2). But as the recent scandal involving the country’s multi-billion-dollar pilgrims’ fund, TH, shows, concerns over their financials can quickly escalate and lead to wider systemic risks. This is not to mention the erosion in confidence of the social and religious values that these institutions are expected to uphold. As Malaysia heralds the adoption of Islamic finance across all financial institutions, including DFIs and cooperatives, it is worth asking, just how Islamic’ are these institutions?

The fact that Malaysia’s DFIs and banking cooperatives are reporting comparable, if not, higher profits than commercial banks, on the back of aggressive lending, is an issue. While Islam allows both profit and debt, the latter is not to be taken lightly and profiting from debt is to earn riba. Admittedly, not all DFIs and cooperatives adhere to Islamic finance but as mentioned earlier, Islamic finance in Malaysia currently mirrors its conventional counterpart. Thus even if all of the institutions become Islamic, the form would in essence, still be conventional finance.

Further, any wrongdoing by the DFIs can pose reputational and Shariah non-compliance risks to the Islamic finance sector because 7.4 percent of the 25.6 percent market share in 2014 came from DFI assets while 18.2 percent was from Islamic banks (Table 2). This means that DFIs contribute almost one-third of the Islamic assets in Malaysia.

Lending on a High

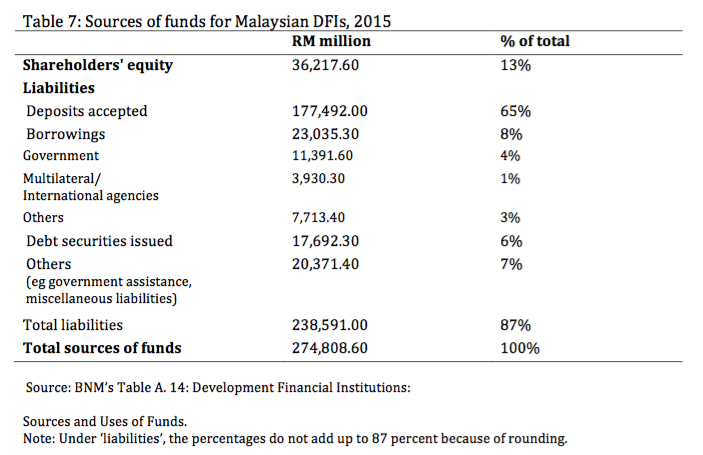

To put into proper context the DFIs’ net loans to deposit and short-term funding ratios, one needs to understand whether they have alternative sources of funding. According to BNM’s 2015 Financial Stability and Payment Systems Report, 65 percent of their funding came from deposits, including those by statutory bodies (Table 7). Given that deposits are their main source of funding, the fact that their net loans are two to three times more than their deposit and short-term funding is worrying and questionable from a Shariah perspective.

The government and central bank seem aware of these issues and have been taking steps, since early 2000, to ameliorate them. In BNM’s Financial Sector Masterplan for 2001-2010, its recommendations for DFIs include a ringfencing of the government’s loans, presumably to increase accountability. It then encouraged DFIs to raise funds through the capital market as far as possible. Also, BNM called for a better regulation of the DFIs so that their policies will be brought in line with national policies.[33] Since then, six of the country’s 13 DFIs have come under its watch and a guideline has been issued to enable DFIs to source cheaper funds from the interbank market.[34] Still, as of 2015, debt securities formed only 6 percent of the DFIs’ source of funding while the portion of deposits and government borrowings has increased from 66.7 percent in 2009[35] to 69 percent (Table 7). As the TH scandal reminds us, Malaysia faces reputational and Shariah non-compliance risks if more is not done to tighten regulations for the country’s 13 DFIs.

Lack of Depositor Protection

The other issue that afflicts DFIs and cooperatives in Malaysia is the uneven regulation when it comes to deposit protection. While Germany has more than sufficient deposit insurance for all financial institutions, including its savings and cooperatives banks,[36] Malaysia’s deposit insurance is compulsory only for its conventional and Islamic banks but not the DFIs and cooperatives.[37] This means that in the case of bank runs, depositors of conventional and Islamic banks are assured of receiving a maximum of RM 250,000 each but not all who deposited with DFIs and cooperatives are backed by government guarantees of bailouts. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) picked up on this issue when invited by the Malaysian government to assess its deposit insurance system.

In a report dated February 2013, the IMF said, “Membership in PIDM is compulsory for all licensed commercial and Islamic banks. However, there are other deposit taking institutions which together comprise about 10 percent of the deposits in the banking system which are not members of PIDM. The majority of these deposits are held in institutions that are subject to explicit or implicit government guarantees of their deposits (although these institutions do not pay a premium for the coverage) but there are others (credit cooperatives) that are not part of any deposit insurance system and do not have such guarantees. It is not clear that the credit cooperatives are subject to the same level of supervision and regulation as the commercial banks.” IMF added that the deposit-taking institutions, which do not pay premiums for deposit insurance but have explicit or implicit government guarantees, are gaining an unfair advantage over banks which pay deposit insurance. IMF rated Malaysia largely compliant’ for this aspect of the assessment.[38]

Playing with the Pilgrims’ Funds

Three years on, the situation has become worse with the TH scandal. Being a DFI, its deposits are not insured by PIDM but Section 24 of the TH Act provides for a government bailout should the institution falter. This, however, may not mean much at a time of drying government coffers. Further, the nation’s pilgrims’ fund is also guilty of blurring the lines between deposits and investments. This creates two issues, one of which is the difficulty in rationalising the products to determine whether they qualify for deposit insurance. The other issue is more alarming because it involves the extent of TH’s Shariah-compliance.

TH is currently using terms such as deposits’ alongside bonus’ or what is commonly cited in the press as dividends’. This creates a Shariah issue because deposits under the wadiah (safekeeping) contract should bear no return while those under investment-type of contracts such as mudaraba should pay market-based returns. TH, and Islamic banks in dual systems such as Malaysia, however face the problem of capital flight if their returns on deposits are lower than conventional banks. Thus, they haveturned the contract into a wadiah yad dhamanah (safekeeping with guarantee) where the banks will get to invest their customers’ monies in exchange for providing a principal guarantee. The banks then use hibah (gift) as a concept to pay depositors rates that match what other banks are paying. While technically allowed in Shariah, this is one of numerous examples of how Islamic banks conform to the Shariah in form but not spirit. In essence, the Islamic banks have devised a way to operate just like their conventional counterparts.

In fact, IFSA 2013 precisely tries to solve this conundrum by requiring its Islamic banks to make a distinction between deposits and investments. This new regulation interestingly does not apply to TH since it is not regulated by the central bank. It does however apply to another DFI, Bank Rakyat, which is under BNM supervision.[39] This uneven regulation raises the question of why some financial institutions provide deposit protection while others do not and why some such as TH can continue to blur the lines between deposit and investments when others have had to make a distinction between the two. As the TH scandal shows, these conundrums lead to questions not only on the financial institution’s going concern but also the extent to which it upholds the Islamic values that it purports to serve its customers.

Why the Uneven Regulation?

In Malaysia, however, the DFIs and cooperatives seem sidelined in the financial institutional framework. PIDM is a government-backed insurance scheme, whose board of directors include the Ministry of Finance (MoF)’s Secretary General of Treasury as well as the Central Bank Governor. Both MoF and BNM also share regulatory oversight of the DFIs so why exclude these institutions from the deposit insurance scheme?

The answer could be in the qualification criteria for PIDM. The premiums paid by the banks depend on their scoring, which have quantitative and qualitative components. The former, which has a 60 percent weightage, looks into indicators such as the capital buffer, return on risk-weighted assets ratio and loans to deposits ratio.[40] The qualitative aspect, on the other hand, evaluates among others, whether the bank has received any letter of warning from a regulator on a deficient or non-compliant aspect of its business and whether the bank has received any form of assistance, financial or otherwise, from BNM or PIDM.

Given the issues raised in this paper about the DFIs’ unexpectedly high profitability, aggressive lending and dependency on government assistance, it is perhaps not surprising why these institutions cannot be held on par with commercial banks when it comes to regulations. This however begs more questions: is the government guarantee then an implicit recognition and encouragement of the DFIs and cooperatives’ substandard practices? Should not more have been done to bring standards on par with commercial banks as is the case in Germany?

Lessons for Islamic Finance Reform

The study of Germany’s financial system shows that a truer type of Islamic finance is possible. The presence of cooperatives and savings banks in the system has led to higher financial inclusion and stability, albeit at a lower profitability when compared internationally. Both institutions embody values such as being welfare-oriented that should have resonated with Islamic banks in Malaysia.

The banks’ business models are also supported by an institutional set-up that forces’ or makes it conducive for them to cultivate long-term relationships with customers. This is how the banks gather in-depth knowledge of the financing needs and risk profiles of their retail customers and businesses. For example, the savings and cooperatives banks in Germany follow a regional principle’, where deposits from a region can only be disbursed for loans within the region. This aligns the banks’ interest with customers in that they both benefit from the region’s economic development and prevent the bank from cherry-picking’ customers from more prosperous regions.[41]

Further, the ownership structure of both banks has elements of protection against the profit-maximisation goal of certain types of shareholders. The cooperatives, by nature, are owned by their customers, who exert pressure on the banks’ management to advance their interests. Interestingly, the savings banks in Germany have the legal status of being institutions incorporated under public law’. This protects them from being taken over by “private banking groups or investors, whose principal aim is generally to increase profits.”[42] Thus, the savings banks have no owner and cannot be sold.

Care too seems to have been taken to reduce an abuse of power. The population in the region that the savings bank operates is represented in its supervisory board through representatives from the city council. But first, these representatives need to prove that they are financially-competent.

Contrast these with Malaysia. Making the Islamic banks run head-to-head alongside their conventional counterparts in a celebrated dual system has been more of a curse than a blessing. The Islamic banks have had to compete tooth and nail for profits in an environment that does not allow them to pay any more than lip service to social welfare considerations. Nor the time and space to better understand customers. The constant competition for higher numbers, especially to a parent who owns both conventional and Islamic banking businesses, naturally means the interests of the Islamic bankers are more aligned with the profit-driven ambitions of their shareholders than any customer.

Rethinking the Drivers

It is thus worth questioning Malaysia’s strategy of pushing Islamic finance via its private sector. For it to succeed in creating a truer Islamic finance system, Malaysia needs a government and policy makers who can envision a whole economic system, and within it, a banking structure that, like Germany, balances the need to be profitable with social welfare considerations. For starters, Malaysia may need to rethink the drivers of her financial system. Germany’s savings and cooperative banks are thriving because they are still a large part of the system. The private sector commercial banks contribute only one-third of assets. With size comes bargaining power and financial clout to be as they are. The German government has resisted calls to privatise more of its banking system. Malaysia on the other hand, is led by the private sector, with profit-maximisation as the raison d`etre. Can Islamic finance thrive in such an environment?

Secondly, there may need to be institutional prop-ups to protect the social welfare functions of this new system from the incursions of the profit-driven capitalists. The public ownership of the savings banks in Germany for example, is a deliberate move to protect them from the ever pervasive hands of private investors. The regional principle’ also has shown to be effective in securing the long-term commitment of the savings and cooperative banks. A natural outcome of which is their in-depth understanding of that region’s customers’ needs. Coincidentally, this is exactly what Islamic banks need if they are to transform themselves, under IFSA 2013, from being mere financial intermediaries to investment bridges.

Thirdly, this study’s comparison between Germany and Malaysia has shown the need to condition or educate Malaysians on a different risk-reward system if we are to truly embrace Islamic finance. The analysis of the German system indicates a trade-off between profits, stability and financial inclusion. The Germans seem to have given up more opportunities for profit-making in exchange for a stable system and one that includes the less credit-worthy members of its society and SMEs. This is more in line with the Shariah of Islam. Malaysians may thus need to be weaned off their private sector tendencies for guarantees and predictable returns. In exchange, we may finally be able to walk the talk with a form of Islamic finance that genuinely rewards investors for their effort and risks taken.

Fourthly, if Malaysia is truly keen to build a genuine Islamic finance industry, there needs to be a better regard for shariah-compliance. As this research shows, the country has taken one too many questionable steps in its fixation to register ever higher numbers for Islamic finance. While Malaysia has undeniably built an entire infrastructure which spans education, regulations and ancillary supports such as Islamic capital and money markets, the country has also gained a reputation, not entirely unfounded, for allowing a number of questionable practices and contracts in Islamic finance. While steps have also been taken to align Malaysia’s Shariah standards with the Middle East, the other dominant region of Islamic finance, a truer type of Islamic finance may only be possible with a rethink of the drivers of her financial system.

Cleaning Up the DFIs and Cooperatives

In rethinking the drivers, the DFIs and cooperatives in Malaysia actually hold the most potential to help bring about genuine Islamic finance. As Germany has shown, the spirit of mutuality, as in the sharing of burdens and rewards, which is among the key features of Islamic finance, is better uplifted through institutions that are welfare-oriented and thus, not strictly profit-maximising. In Malaysia however, the DFIs and cooperatives seem to be sidelined. Their depositors receive no deposit insurance protection, regulatory oversight remains weak and in academia too, there is scant research on their issues. If Malaysia is to lead the world in Islamic finance, it will need more commitment from the government and regulator to clean up its DFIs and cooperatives and bring them to national standards.

For cooperatives specifically, because of their different business model, one may argue that their members should not be covered with deposit insurance because the idea is for them to partake in the cooperative’s financial performance. Somewhat like musharakah, the profit-and-loss sharing contract in Islamic finance. The reality, however is that the collapse of any financial institution in a country poses systemic risks to the entire financial sector through a loss of confidence. Hence the series of government bailouts for its troubled cooperatives since at least 30 years ago.[43] Also the sharing of profits and losses works best in a functional system with proper governance. This, however, is a major issue for the cooperatives in Malaysia, and it needs rectification.

Overtly, there are numerous attempts by the government to improve the regulatory oversight of its DFIs and cooperatives. For the latter specifically, there is the second National Cooperative Policy (NCP) for the years 2011-2020, a number of amendments to the Cooperative Act and the setting up of the Malaysia Cooperative Societies Commission (MCSC) under the Ministry of Domestic Trade, Cooperatives and Consumerism. But the sector is still riddled with issues of corporate governance, accountability and poorly qualified or ignorant management. Othman et al (2013) cited an MCSC 2010 economic report[44] for instances of cooperative board members abusing their positions. According to the published research, “Some even meddle with illegal investment activities, characterised by dodgy quick-rich schemes. The absence of authentic cooperative principles and values has resulted in certain unscrupulous and irresponsible people in the society to form cooperatives and take advantage by collecting investments and deposits for their own personal gain.”[45]

Another issue with DFIs and cooperatives in Malaysia that needs rectification is the number of academic research reports on their challenges and viability. So far, research on these institutions is a fraction of what has been published about the conventional and Islamic banks in Malaysia.[46] To help DFIs and cooperatives play their much needed roles in society, academics need to extend their research into the issues facing these institutions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, not only are the German banks, particularly its savings and cooperative banks, more Islamic than Islamic banks in Malaysia, their entire system upholds the Islamic values of justice, equity and social welfare better than any Muslim country. The German model is proof that these Islamic values are sound and time-tested in a different cultural setting. In one word, universal. In Malaysia, however, while BNM has made a commendable attempt to right the ship through IFSA 2013, it has in effect, pushed Islamic banks in the opposite direction. This study thus concludes with two reform recommendations: a rethink of the economic drivers in Malaysia and a sprucing up of the DFIs and cooperatives’ balance sheets towards national standards. Until then, Germany will continue to show the way because their banks, leaving aside the riba elements, are indeed more Islamic than the financial institutions in Malaysia.

With more than 10 years of experience as financial journalist and banker, Rosana Gulzar Mohd is pursuing her Master of Science in Islamic finance at INCEIF, Malaysia. She graduated from Nanyang Technological University (Singapore) with a Second Upper Class Honours in Communications Studies in 2003. Following stints with several business newspapers, she was headhunted to join HSBC in Singapore. Her work, which involved investment communications for retail bankers, included helping the bank manage raging customers during the 2008 global financial crisis. In 2010, she joined HSBC’s global Islamic banking business in Dubai and led HSBC Amanah’s corporate communications efforts across their retail, commercial and investment banking businesses in Southeast Asia, the Middle East and the UK. She has also completed Chartered Financial Analyst examination level 1. As an MSc candidate at INCEIF, her research interest is the reform of Islamic banking.

References

Abdul Latiff, R. “Bank Kerjasama Rakyat Malaysia Berhad: A case of a cooperative Islamic bank in Malaysia” Bangi: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 2010.

Ahmed, H. Product development in Islamic banks. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011.

A. K. Malim, Nurhafiza. Financial Intermediation Costs in Islamic Banks: The Role of Bank-specific, Market-specific and Institutional-governance Factors. INCEIF PhD dissertation, 2015

Al-Muharrami S. M. and D. Hardy. “Cooperative and Islamic Banks: What can they Learn from Each Other?” 2013.

Amir Alfatakh. “The Shift of Mudharabah Products into Investment Accounts. Market Impact and Its Acceptance.” 2015.

Anuar, K., Mohamad, S., and M. E. Shah. “Are Deposit and Investment Accounts in Islamic Banks in Malaysia Interest Free?” JKAU: Islamic Economics 27, no. 2 (2014): 27ÔÇô55.

Attorney’s General Chambers. “Malaysia deposit insurance corporation (Differential premium systems in respect of deposit-taking members) (Amendment) Regulations 2015.” 2015.

Azmat, S., Skully, M., and K. Brown. “Can Islamic banking ever become Islamic?” Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 34 (2015): 253-272.

BAFIN, German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority. “Deposit protection and investor compensation.” 2016. http://www.bafin.de/SharedDocs/FAQs/EN/ Consumers/BankenBauSparkassen/SicherungEntschaedigung/03_institutssicherung.html?nn=3024646

Bank for International Settlements. “Basel Committee on Banking Supervision

Basel III: the net stable funding ratio.” 2014. Retrieved from http://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d295.pdf

Bank for International Settlements. “Datuk Zamani Abdul Ghani: Role of development financial institutions in the financial system.” 2005. http://www.bis.org/review/r050923e.pdf

Barnes, W. “Islamic finance sits awkwardly in a modern business school (Interview with Timur Kuran).” 2013. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/ee2a2b36-9de5-11e2-9ccc-00144feabdc0.html#axzz3pjcHa6LI

Beck, T., Hesse, H., T. Kick, and N. von Westernhagen. “Bank ownership and stability: evidence from Germany.” Unpublished Working Paper. Washington, DC: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 2009.

Bernama. “Tabung Haji warns of perils of withdrawing haji deposit.” 2016. http://www.theborneopost.com/2016/03/15/tabung-haji-warns-of-perils-of-withdrawing-haji-deposit/

Bloomberg. “Maybank says Islamic loans overtake conventional financing for the 1st time.” 2016. http://www.straitstimes.com/business/banking/maybank-says-islamic-loans-overtake-conventional-fincancing-for-the-1st-time

BNM. “Bank Negara: Financial Stability and Payment Systems Report 2014.” 2014. http://www.bnm.gov.my/files/publication/fsps/en/2014/fs2014_book.pdf

BNM. “Deputy Governor’s Keynote Address at the Launch of Islamic Finance Country Report for Malaysia 2015.'” 2015. http://www.bnm.gov.my/index.php?ch=en_speech&pg=en_speech_all&ac=564

BNM. “Financial sector blueprint 2011ÔÇô2020.” 2011.

BNM. “Non-bank Intermediaries in Malaysia, Risk developments and assessment of financial stability in 2011.” 2011. http://www.bnm.gov.my/files/publication/fsps/en/2011/cp01_001_whitebox.pdf

Brown, Ellen. “Publicly-owned Banks as an Instrument of Economic Development: The German Model.” 2011. http://www.globalresearch.ca/publicly-owned-banks-as-an-instrument-of-economic-development-the-german-model/27054

Brown, Ellen. “Why Public Banks Outperform Private Banks: Unfair Competition or a Better Mousetrap?” 2015. http://ellenbrown.com/2015/02/10/why-public-banks-outperform-private-banks-unfair-competition-or-a-better-mousetrap/

“Central Bank of Malaysia Act 2009.”http://www.bnm.gov.my/documents/act/cba2009_01.pdf

Chan-Lau, J. A., and A. N. R. Sy. “Distance-to-Default in Banking: A Bridge Too Far?” 2006.

Chapra, M. U. Towards a just monetary system 8 IIIT, 1985.

Charap, J., and S. Cevik. “The behaviour of conventional and Islamic bank deposit returns in Malaysia and Turkey.” IMF Working Papers (2011): 1-23.

Chong, B. S., and M. H. Liu. “Islamic banking: interest-free or interest-based?” Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 17, no. 1 (2009): 125-144.

Consumers Association of Penang. “Co-ops heading for trouble again?” n.d. http://www.consumer.org.my/index.php/focus/cooperative-scandals/391-history-of-cooperative-scandals

Consumers Association of Penang. “History of cooperative scandals.” n.d. http://www.consumer.org.my/index.php/focus/cooperative-scandals/391-history-of-cooperative-scandals

Detzer, D., J. Creel, F. Labondance, S. Levasseur, M. Shabani, J. Toporowski and C. A. R. Gonzalez. “Financial systems in financial crisis’An analysis of banking systems in the EU.” Intereconomics 49, no. 2 (2014): 56-87.

Deutsche Bundesbank. “Deposit protection and investor compensation in Germany.” Deutsche Bundesbank monthly report July 2000. 2000

Deutsche Bundesbank. https://www.bundesbank.de/Navigation/EN/Home/home_node.html

Deutsche Bundesbank. “Structural developments in the German banking sector.” Deutsche Bundesbank monthly report April 2015. 2015.

El-Gamal, M. A. “Islamic bank corporate governance and regulation: A call for mutualization.” Rice University, 2005.

El-Gamal, Mahmoud. “Microfinance Experience versus Credit UnionÔÇôGrameen I.” 2009. http://elgamal.blogspot.com/2009/08/microfinance-experience-vs-credit-union.html

Farook, S., Hassan, M. K., and G. Clinch. “Profit distribution management by Islamic banks: An empirical investigation.” The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 52, no. 3 (2012): 333-347.

Fitch Ratings. “Islamic Finance in Malaysia: An Evolved Sector.” 2016. https://www.fitchratings.com/site/fitch-home/pressrelease?id=999620

German Savings Banks Association. “Constitutive Elements of a (German) Savings Bank.” 2012. http://www.Sparkassenstiftung.de/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf/2012_08_ConstitutiveElements.pdf

“Germany’s banking system. Old-fashioned but in favour. Defending the three pillars,” The Economist, November 10th, 2012. http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21566013-defending-three-pillars-old-fashioned-favour

“Germany and economics. Of rules and order. German ordoliberalism has had a big influence on policy during the euro crisis,” The Economist, May 9th, 2015. http://www.economist.com/news/europe/21650565-german-ordoliberalism-has-had-big-influence-policy-during-euro-crisis-rules-and-order

Gulzar, R., and M. Masih. “Islamic banking: 40 years later, still interest-based? Evidence from Malaysia.” German: University Library of Munich, 2015.

Hassan, Fabien. “A View From Germany I ÔÇô How the three-pillared German Banking System has gotten through the crisis.” 2014. http://www.finance-watch.org/hot-topics/blog/851-view-from-germany-1

Hassan, Fabien. “A View From Germany II ÔÇô The financing of the German economy.” 2014. http://www.finance-watch.org/hot-topics/blog/870-view-from-germany-2

Hau, H., and M. Thum. “Subprime crisis and board (in-) competence: private versus public banks in Germany.” Economic Policy 24, no. 60 (2009): 701-752.

Hegazy, Walid S. “Contemporary Islamic Finance: From Socioeconomic Idealism to Pure Legalism.” Chicago Journal of International Law 7: no. 2 (2007).

Iannotta, G., G. Nocera, and A. Sironi. “Ownership structure, risk and performance in the European banking industry.” Journal of Banking & Finance 31, no. 7 (2007): 2127-2149

IMF. “Germany: Technical Note on Banking Sector Structure.” Country Report No. 11/370. 2011.

IMF. “Malaysia: Financial sector assessment program, financial sector performance, vulnerabilities and derivatives ÔÇô Technical note.” Country Report No. 14/98. 2014.

IMF. “Malaysia: Financial sector assessment program, core principles for effective deposit insurance systems. Detailed assessment of observance.” 2013.

Islam, M. A. “An Appraisal of the Performance of Two (2) Development Financial Institutions (DFIS) in Malaysia.” Management 1, no. 7 (2012): 64-74

Khan, F. “How “Islamic” is Islamic Banking?” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 76 (2010): 805ÔÇô820.

KPMG. “Financial System of Malaysia.” http://www.kpmg.com.my/kpmg/publications/tax/I_M/Chapter5.pdf

Malaysia Chronicle. “Zeti warned Najib of financial crisis at Tabung Haji but he made it worse: Rm 1 bil bailout looms?” 2016. http://www.malaysia-chronicle.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=610188:zeti-warned-najib-of-financial-crisis-at-tabung-haji-but-he-made-it-worse-rm1-bil-bailout-looms?&Itemid=2#axzz3yMZOgSya (blocked on computers but accessible through smartphones)

“Malaysia sees more unequal wealth distribution than its Asian peers ‘ study.” Theedgemarkets.com. 2015. http://www.theedgemarkets.com/my/article/malaysia-sees-more-unequal-wealth-distribution-its-asian-peers-‘-study

Marktanner, M. “60 Years of Social Market Economy Formation, Development and Perspectives of Peacemaking Formula.” 170-188. 2010.

Mayer, A. E. “Islamic Banking and Credit Policies in the Sadat Era: The Social Origins of Islamic Banking in Egypt.” Arab Law Quarterly 1, no. 1 (1985): 32.

MIDA. “Banking, Finance & Exchange Administration.” http://www.mida.gov.my/home/banking,-finance-&-exchange-administration/posts/

Milne, R. S. “Levels of corruption in Malaysia: A comment on the case of Bumiputra Malaysia Finance.” Asian Journal of Public Administration 9, no. 1 (1987): 56-73.

Ministry of Finance, Malaysia. “Monetary and Financial Developments Economic Report.” 2008/2009. http://www.treasury.gov.my/pdf/economy/er/0809/chapter5.pdf

“Mutually assured existence,” The Economist, May 13th, 2010. http://www.economist.com/node/16078466?story_id=16078466

New Straits Times. Help for troubled coops to stop. 2005.

Othman, A., Kari, F., and R. Hamdan. “A comparative analysis of the co-operative, Islamic and conventional banks in Malaysia.” American Journal of Economics 3, no. 5C (2013): 184-190.

Othman, I. W., Mohamad, M., and A. Abdullah. “Cooperative Movements in Malaysia: The Issue of Governance.” International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering 7, no. 6 (2013).

Rehman, S. S., and H. Askari. “An Economic IslamicityIndex (EI2).” Global Economy Journal 10, no. 3 (2010).

Reuters. “Malaysian banks race to pin down fleeing deposits.” 2015. http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/10/07/malaysia-banks-idUSL4N11S2EZ20151007

Reuters. “EU, Germany head for clash over deposit insurance plan.” 2015. http://www.reuters.com/article/eu-deposits-germany-idUSL5N11H3B420150911

Schmielewski, F., and T. Wein. “Are private banks the better banks? An insight into the principalÔÇôagent structure and risk-taking behavior of German banks.” Journal of Economics and Finance (2012): 1-23

Siddiqi, M. N. Economics: An Islamic Approach. Institute of Policy Studies, 2001.

“Special Report: The shariah debate on Islamic financing.” Theedgemarkets.com. 2015. http://www.theedgemarkets.com/my/article/special-report-shariah-debate-islamic-financing

Standard & Poor’s. “Cooperative Banking Sector Germany.” 2015. https://www.dzbank.de/content/dam/dzbank_de/de/home/profil/investor_relations/Ratingreports/S&P_Report%20GFG_Nov2015_neu.pdf

Thomes, Paul. “The Impact of Crises on the Savings Banks Institutions in Germany.” 2013. http://www.savings-banks.com/SiteCollectionDocuments/Thomes.pdf

Wilson, R. Legal, regulatory and governance issues in Islamic Finance. Edinburgh University Press, 201

[1] Barnes, W. (2013). Islamic finance sits awkwardly in a modern business school (Interview with Timur Kuran). Retrieved from http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/ee2a2b36-9de5-11e2-9ccc-00144feabdc0.html#axzz3pjcHa6LI

[2] Tabung Haji is a development financial institution (DFI) that is not regulated by the central bank. It falls under the auspices of the Ministry of Finance, which is headed by Malaysia’s Prime Minister (PM). Concerns over the institution came to a head in January 2016 when letters from the BNM governor, Zeti Akhtar Aziz, warning that TH is insolvent and that its reserves were in the red, were leaked to the press. The letters were sent to the PM’s office and TH’s chairman. TH assured contributors that the deposits are safe even as the possibility of a RM 1 billion government bailout was raised. This is because the TH Act provides this guarantee should the institution falter. In a bid to stem withdrawals, a minister in the PM’s Department, Datuk Seri Jamil Khir Baharom said that depositors who withdrew their savings will lose their turn to perform the pilgrimage for up to 70 years.

[3] BNM’s 2015 Financial Stability and Payment Systems Report. Table A.2 Key Financial Indicators ÔÇô Islamic banking and takaful sectors.

[4] Maybank says Islamic loans overtake conventional financing for the 1st time. Bloomberg. 3 March 2016.

[5] Azmat, S. et al. (2015). Can Islamic banking ever become Islamic?

Chong, B. S., & Liu, M. H. (2009). Islamic banking: interest-free or interest-based?

Khan, F. (2010). How “Islamic” is Islamic Banking? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 76, 805ÔÇô820.

[6] Charap, J., & Cevik, S. (2011). The behaviour of conventional and Islamic bank deposit returns in Malaysia and Turkey.

Gulzar, R., Masih, M. (2015). Islamic banking: 40 years later, still interest-based? Evidence from Malaysia.

[7] Presentation: The Shift of Mudharabah Products into Investment Accounts. Market Impact and Its Acceptance’ by Standard Chartered Saadiq, 18 November 2015.

[8] Ibid. Pg 46.

[9] The World Bank’s 2014 Global Findex survey and SME Finance Forum’ which cites SME Performance Review EU, 2011′.

[10] The data are sourced through Bankscope. While limitations abound, efforts have been made to plug the gaps as far as possible. For example, while the priority is to use the consolidated statements of each bank, when these are unavailable, their unconsolidated statements have been used. For the Malaysian financial institutions, the limitation is that while the list is mostly aligned with BNM, some institutions, such as Lembaga Tabung Haji and the Credit Guarantee Corporation Berhad could not be included as Bankscope does not have their data and they are not publicly available. Additionally, BNM classifies Bank Kerjasama Rakyat Malaysia Berhad as a DFI when the bank is in actual fact, a cooperative. This study thus classifies Bank Rakyat as a banking cooperative to more accurately reflect its business.

[11] Source: IMF. (2011). Germany: Technical Note on Banking Sector Structure, Country Report No. 11/370, pg 25.

[12] The German Financial System and the Financial Crisis, Detzer, Daniel; Intereconomics/Review of European Economic Policy, March 2014, v. 49, iss. 2. Pg 63-4.

[13] The study involved a ranking of 208 Islamic and non-Islamic countries based on their adherence to the theoretical workings of an Islamic economy. The researchers developed 113 proxies under three broad headings; achievement of economic justice and sustained economic growth, broad-based prosperity and job creation, and lastly, the adoption of Islamic economic and financial practices.

[14] Mayer, A. E. 1985. Islamic Banking and Credit Policies in the Sadat Era: The Social Origins of Islamic Banking in Egypt. Arab Law Quarterly, pg 36-7.

[15] Hegazy, Walid S. (2007) “Contemporary Islamic Finance: From Socioeconomic Idealism to Pure Legalism,” Chicago Journal of International Law: Vol. 7: No. 2, Article 13. Pg 585-9.

[16] El-Gamal, M. A. (2005). Islamic bank corporate governance and regulation: A call for mutualization. Pg 9-15.

[17] Malaysia has nine types of cooperatives such as banking, credit, housing and farming but this study focuses on the banking cooperatives because Bankscope has data only on this group. It is the largest type of cooperative in terms of assets and profitability. Noteworthy also is the fact that the group is made up of only two members; Bank Rakyat and Bank Persatuan Malaysia Berhad but data in this group is mainly from Bank Rakyat as there is limited data from Bank Persatuan; it not being regulated by the central bank.

[18] BNM Financial sector blueprint 2011-2020, p 18.

[19] Given their ideological link, the Malaysian Islamic banks are specifically compared against the German savings banks.

[20] Theedgemarkets.com. (2015). Special Report: The shariah debate on Islamic financing.

[21] Public Lecture by the Recipient of The Royal Award for Islamic Finance 2014, Datuk Dr Abdul Halim Ismail (Malaysia).

[22] Obtained from Table 3: (2.53-2.37/2.37) * 100.

[23] Obtained from Table 3: (9.10-9.03/9.03) * 100.

[24] BNM’s Financial sector blueprint 2011-2020′, p 49.

[25] Theedgemarkets.com. (2015). Special Report: The shariah debate on Islamic financing.

[26] Affin Bank Berhad versus Zulkifli bin Abdullah.

[27] Seeni Mohideen, H. (2006). Affin Bank Bhd vs Zulkifli Abdullah ÔÇô Shariah perspective. Malayan Law Journal. Pg 3.

[28] This was done by adding clause no. 58 to the Central Bank of Malaysia Act 2009.

[29] DFIs and cooperatives contribute 14.4 percent of assets in the banking system in 2014 (Table 2).

[30] New Straits Times. (2005). Help for troubled coops to stop.

Othman, I. W. et al., (2013, January). Cooperative Movements in Malaysia: The Issue of Governance.

[31] The anomaly for ROAE in 2006 is because the numbers for Islamic banks and DFIs are inflated by one institution in each category, namely Bank Islam and Bank Simpanan Nasional (National Savings bank). Otherwise, the trend holds.

[32] Al-Muharrami, S. M., & Hardy, D. (2013). Cooperative and Islamic Banks: What can they Learn from Each Other? Pg 8.

[33] BNM Financial Sector Masterplan for 2001-2010, pg 91.

[34] Monetary and Financial developments, Economic report, 2008/2009. Ministry of Finance. Pg 138.

[35] Ibid, pg 139.

[36] BAFIN, Deposit protection and investor compensation. http://www.bafin.de/SharedDocs/FAQs/EN/Consumers/BankenBauSparkassen/SicherungEntschaedigung/03_institutssicherung.html?nn=3024646

[37] PIDM (Perbadanan Insurans Deposit Malaysia) http://www.pidm.gov.my/For-Public/About-Deposit-Insurance/Member-Banks

[38] Largely compliant means “when only minor shortcomings are observed and the authorities are able to achieve full compliance within a prescribed time frame”.

[39] Bank Rakyat 2013 annual report, page 181.

[40] Malaysia deposit insurance corporation (Differential premium systems in respect of deposit-taking members) (Amendment) Regulations 2015, pg 23, 32.

[41] German Savings Banks Association. (2012). Constitutive Elements of a (German) Savings Bank.

[42] Ibid.

[43] New Straits Times. (2005). Help for troubled coops to stop.

[44] The report seems to have been removed from the website.

[45] Othman, I. W. et al., (2013). Cooperative Movements in Malaysia: The Issue of Governance.

[46] Ibid, Islam, M. A. (2012). An Appraisal of the Performance of Two Development Financial Institutions in Malaysia.