Effectiveness of Shariah Committees in the Malaysian Islamic Financial Institutions: The Practical Perspective

By Mohamad Shamsher and Zulkarnain Muhamad Sori

Abstract

An effective system of rules, practices and processes by which Islamic Financial Institutions (IFIs) are directed and controlled to ensure their business operations are Shariah-compliant has important implications on their reputation and their future growth. The Shariah Committee is a mandated requirement by the central bank on every Islamic Financial Institution (IFI) to ensure the expected level of Shariah-compliance in their business operations. Unlike their conventional counterparts that focus only on maximizing the wealth of shareholders, IFIs has an extra responsibility to protect the interests of all stakeholders (including shareholders) and ensure that no injustice of any kind is committed to any stakeholder. In performing their responsibilities, the Shariah Committees experience challenges both within and outside their institutions that adversely affect their effectiveness as gatekeepers of Shariah-compliance and hence mitigating Shariah non-compliance risk. Specifically, issues such as degree of independence, confidentiality, competence, and consistency and information disclosure might be compromised and mitigates the effectiveness of Shariah Committees.

Keywords: Shariah Governance, Shariah Committee, Islamic Financial Institutions, Independence, Competence, Consistency

The concept of Shariah governance has its foundation in the Qur’an and the Sunnah. It is the divinely ordained guidelines of conduct for Muslims in all aspects of their life, which includes financial matters. For financial transactions, any element of injustice to participants in any form and the presence of interest (riba) is absolutely forbidden. The Shariah-based governance guidelines uphold the elements of transparency, fairness and accountability, and focus on the interest of all stakeholders. Weak or ineffective governance has always been the major cause of fiascos in both conventional and Islamic financial markets. In the Islamic financial markets, the failures of Ihlas Finance in Turkey, Islamic Bank of South Africa, and the Islamic Investment Companies of Egypt as well as the commercial losses of Dubai Islamic Bank are evidence of such fiascos.

Malaysia, being the global hub for Islamic finance, has in place a well-structured Shariah Governance Framework to support its growing Islamic finance industry. One of the requirements of the framework is that it is mandatory for all Islamic financial institutions (IFIs) to set up a Shariah Committee to provide independent oversight on the whole chain of activities of the IFI to ensure that all the operations are Shariah-compliant. Any failures to effectively enforce Shariah governance will create reputational risks and erode the credibility and competitiveness of the Islamic finance industry.

This article briefly highlights some real challenges for Shariah Committees in IFIs in fulfilling their expected responsibilities.

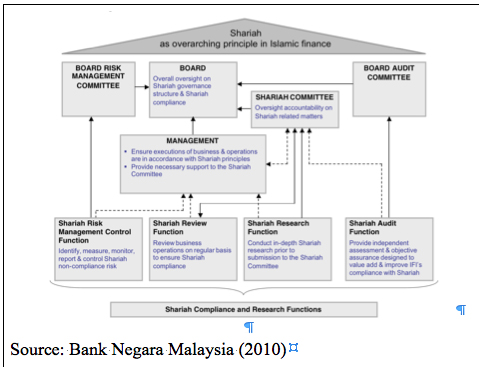

The Malaysian Central Banks Shariah Governance Framework

Shariah governance is a set of rules and regulations put into place by the regulators for all Islamic financial institutions to comply with in all aspects of their operation. The Malaysian Central Bank (Bank Negara Malaysia or in simply BNM) has introduced the Shariah Governance Framework for Islamic Financial Institutions (SGF) effective from 1 January 2011. The framework enhances the role of the Board of Directors, Shariah Committee and Management on Shariah matters, including enhancing the relevant key organs in executing the Shariah-compliance and research functions. The organizational structure of the framework depicted in Figure 1 below indicates a two-tier Shariah governance infrastructure comprising of two (2) vital components namely the Shariah Advisory Council (SAC) at the Central Bank and an internal Shariah Committee established in each IFI. The SAC has the ultimate authority on any financial matter relating to Islamic business operations, activities or transactions. The Shariah Committee is given a mandate to provide guidance to the respective IFIs on Shariah matters.

To ensure effectiveness of the framework, four main functions are outlined, namely, the Shariah Risk Management Control Function, Shariah Review Function, Shariah Research Function and Shariah Audit Function. Besides the key players of Shariah Governance and the four functions, Figure 1 also showed the line of communication or reporting between key players and main functions.

Source: Bank Negara Malaysia (2010)

Figure 1: Shariah Governance Framework Model for Islamic Financial Institutions.

There are seven principles outlined in the framework to ensure effective Shariah-compliance on part of the IFIs. Among others, the Board of Directors is expected to understand the Shariah non-compliance risks associated with Islamic finance business and operations and its implications to the respective IFIs. The ultimate responsibility of Shariah-compliance lies with the Board of Directors though the Shariah Committee is the directly responsible gatekeeper. To meet this responsibility, the Shariah Committee is required to have at least 5 members, the majority of whom are Shariah experts (specifically in areas of Fiqh and Usul Fiqh) and at least one of whom is a qualified member in another discipline such as economics, finance or business.

The Shariah Governance Frameworkrequires the IFIs Shariah Committee to be responsible to the Shariah Advisory Council (SAC) at the Malaysian Central Bank. Since 2009, the SAC has legal authority to take action against IFIs if they fail to comply with the issued Shariah guidelines and resolutions. This facilitates the decision making process as IFIs can always refer to the SAC at the Central Bank in the case of ambiguity in the law or any disagreement. Since it is impossible for IFIs to comply fully with Shariah requirements, the form and substance of actual commercial transactions being conventional in nature, there are a lot of contentious issues that requires advice from the SAC in the central bank. SAC, being the central reference point with legal authority, facilitates decisions on contentious issues so as to ensure uniformity in practice. The Shariah Committee will seek advice from the SAC on contentious issues and report to the Board of Directors (BOD) on the recommendations from the SAC. The board of the IFI will then advise the management of what is required to ensure compliance.

Having the framework and effectively enforcing the requirements are two separate issues. The next section discusses some issues raised by chairmen of the Shariah Committees of seventeen Islamic financial Institutions in Malaysia. A well-functioning Shariah Committee is expected to be effective, efficient, independent, consistent, and transparent in its deliberations and decisions, but questions were raised concerning the issues of independence, confidentiality, competence, consistency and disclosure by a Shariah Committee when delivering its responsibilities.

Is the Shariah Committee Really Independent of Management Influence?

It is important for Shariah Committee not to be influenced by the management when deliberating on the compliance of products and services. It is possible that management may not want to compromise on their performance and therefore influence the Shariah Committee to endorse the new product or service that the committee is still not clear about, concerning its compliance status, but that is important for management in order to achieve their profit targets and expected remunerations.

Is the Shariah Committee able to make objective decisions independently, without any form of influence or coercion from management? In fact Shariah Committees can only express opinions that give rise to resolutions, or provide expert testimony, but they do not have the legal authority to ensure that management adhere to these resolutions. From a practical perspective, a substantial amount of resources are usually spent by the management of an IFI in developing the processes and the products, and they are usually keen to fulfil their short-term key performance indicators to earn their targeted remunerations. Furthermore, the Shariah Committee members usually receive remuneration from the IFIs which could lead to legitimizing unlawful or dubious operations, products and services because of the monetary incentive. If this is the case, then the product review could just be perfunctory, with Shariah Committees relenting to IFI management pressure.

In Malaysia, the appointment, removal and renewal of Shariah Committee members in IFIs is regulated directly by the Central Bank. For appointments, the IFI recommends the candidate to the Central Bank with the required details and the final decision is made by the Central Bank after due diligence. The IFI can only request a change or removal of a member to the Central Bank and the latter will have the final decision after due deliberation. The only reasons usually for which the Central Bank removes a member from the committee before his term expires are regular absences from scheduled meetings or health problems. However, with regards to the remuneration to the members by the IFI, the Central Bank does not have any guidelines, and the respective IFIs display significant variation in their scales for remuneration, which vary from just RM1,000 per month to over RM10,000 per month depending on the status of the IFI. Foreign Shariah scholars that are invited by large IFIs are usually more costly as they charge high retention fees. A more effective method to mitigate any potential conflict of interest might be to establish a separate independent fund supervised by the Central Bank that pays a standard remuneration to Shariah Committee members of all IFIs. There should also be standard guidelines for engaging prestigious foreign scholars on Shariah Committees. Standard pay scales would also mitigate the issue of relenting to management pressure

Do the Shariah Reports Serve their Intended Purpose?

In practice, Shariah Committees are required to provide information on their activities through formal reports on an annual basis and to highlight Shariah pronouncements and declarations of Shariah-compliance to the Central Bank. Before an IFI prepares a report, it is required to undergo a Shariah review process by an independent internal Shariah auditor to ascertain the conformance or non-conformance of all transactions. Although there is a standard guideline from the central bank for the collection, compilation, analysis and reporting of information, in practice IFIs need not follow the guideline and can submit their report in any format as long it discloses the required information.

Multiple Appointments ÔÇô Are there Possible Conflicts of Interest?

The rapid growth of the Islamic finance industry on a global scale has led to the increase in the need for more qualified Shariah scholars and has highlighted the issues of multiple appointments of the same scholars in many IFIs. In Malaysia a scholar may not sit on the Shariah Committee of more than one bank, but in many Middle Eastern countries, multiple appointments are allowed and many IFIs take pride in appointing scholars known for their knowledge and reputation and perhaps even their leniency in endorsing products and services of IFIs.

Multiple appointments could lead to conflicts of interest. For example, the Shariah scholars relationship with other members of a Shariah Board could affect the impartiality and objectivity of their decisions, Taking similar views on similar issues under different jurisdictions (in the interest of expediency) might not be objective as the case might actually require different considerations due to different circumstances. Also of concern is the capability of scholars to manage their time to be on many committees at the same time. It is therefore imperative for a proper policy or regulation on this issue to safeguard the credibility of IFIs and the Islamic finance industry. Adopting the Malaysian practice could certainly mitigate if not eradicate the fatwa shopping among IFIs. In Malaysia, Section 16 B (6) of the Central Bank of Malaysia Act 1958 does not allow any Islamic financial institution (IFI) to appoint any member of the Shariah Committee of another Islamic financial institution in the same industry. However, they can be a member of the Shariah Committee of another Islamic finance industry like takaful, but cannot be members of more than two Shariah Committees at the same time.

Are the Fatwas[1] Consistent?

The inconsistency and conflicting views on similar issues in different jurisdictions further clouds the progress and harmonization initiatives in the Islamic finance industry. This compromises the consistency of judgments across IFIs. For example, the General Council for Islamic Banks and Financial Institutions (CIBAFI) reported that ten percent of the 6,000 fatwas issued by different IFIs with over 100 Shariah scholars were not consistent across IFIs (Iqbal and Mirakhor, 2007). The diversity of the interpretation of Shariah affects the determination of certain rulings on a particular issue, where an IFI would accept a new product as being Shariah-compliant in one jurisdiction while other jurisdictions would decide it to be non-compliant. A recent study published by ISRA (2012) reports that more than 54 percent of fatwas issued between Malaysia and the GCC are in direct conflict with each other.

A case in point is the issuance of sukuk in Bahrain, Kuwait and UAE compared to sukuk issued in Malaysia. The former countries consider Malaysian sukuk non-compliant due to the government guarantee on the capital invested. This inconsistency undermines investors confidence and impedes the healthy growth of the Islamic finance industry. However, on a positive note, the inconsistencies in the Shariah resolutions are not totally unexpected as there are different schools of thought that allow a diverse level of interpretation and leniency on the same issue. For example, in the case of bay al inah, the Shafi school of thought allows it to overcome the problem of lack of liquidity in the market on the grounds that suspicion of evil intent is not sufficient to render a transaction invalid. Conversely, the Maliki and Hanbali schools of thought disallows it as it is considered as a legal trick (hilal) to circumvent riba. In Malaysia, though the Shafi school is predominant, it is not imposed on Shariah committee members to base their decisions on a particular school of thought. By default, since most of the Shariah committee members are from the Shafi school of thought, the decisions are biased towards this school.

Conclusion

Malaysia, being the hub of Islamic finance, is committed to provide the required infrastructure, the Shariah Governance Framework, to support this niche and growth industry. In fact, this framework is a part of the 5-year plan for the Islamic finance industry (or formally known as Islamic Finance Industry Framework) chartered to guide a proper growth and competitiveness of the industry.

This paper highlights the challenges faced by Shariah Committees in safeguarding the Shariah-compliance of IFIs in their business operations. The Shariah Governance Framework requires all IFIs to set up and effectively operate Shariah Committees. Effective Shariah governance that emphasizes elements of transparency, trust, and integrity provides credibility to the IFIs and the Islamic finance industry. The role of Shariah Committees has become even more important in the light of the recent turmoil in financial markets. Having the governance infrastructure provides no guarantee of effective governance if there is no an equal commitment from the IFIs to follow through on the guidelines and achieve the expectations.

On a practical note, IFIs require time and a gradual transition to provide the expected effectiveness, and in the process to identify any flaws of the framework of this dynamic industry and economy and to improvise more practical yet objective measures or initiatives to improve the credibility of the Islamic finance industry.

Mohamad Shamsher is professor of finance at the International Centre for Education in Islamic Finance (INCEIF). Previously, he was Dean, Faculty of Economics & Management, Universiti Putra Malaysia. He received his MBA from the Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium and PhD from University of Glasgow. He has taught graduate and post-graduate finance courses and has supervised 25 PhD students. He has authored and co-authored several books and has published articles in the Journal of International Financial Markets, Institution and Money, Global Business and Finance Review, Pacific Accounting Review, International Finance Review, Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, Global Finance Journal, Journal of Asia Pacific Economy, Journal of Islamic Economics and Thunderbird International Business Review, (among others). During 2005-2007 he served as the second-secretary of the Asian Finance Association. His current research interests are in banking, capital markets, Islamic banking, corporate finance; the role of family and politics on corporate performance.

Zulkarnain Muhamad Sori is Professor in the School of Graduate Studies at the International Centre for Islamic Finance (INCEIF), the Global University of Islamic Finance, Malaysia. He is an accountant with consulting, research and teaching experiences in accounting, corporate governance, Shariah governance, accounting for Islamic financial transactions, auditing and entrepreneurship. Dr. Zulkarnain received his Bachelor of Accounting and MSc. (Accounting/Finance) from University Putra Malaysia, and PhD in Auditing & Corporate Governance from Cardiff University, United Kingdom. He has actively published in academic and professional journals, supervised doctoral theses, and edited and published many books.

AAOIFI. (2005). Governance Standard for Ills, No. 1-5. Bahrain: AAOIFI.

AAOIFI. (2010). Governance Standards No. 7: Corporate Social Responsibility, Conduct and Disclosure for Islamic Financial Institutions. Bahrain: AAOIFI.

Ahmed El-Nagar et al., One Hundred Questions & One Hundred Answers Concerning Islamic Banks (Cairo: Islamic Banks International Association, ig8o), p. 20.

Ali, S. S. (2007). Financial Distress and Bank Failure: Lessons from Closure of Ihlas Finance in Turkey. Islamic Economic Studies, Vol. 14, No. 1 & 2, 1-52.

Askari, H., Iqbal, Z., and Mirakhor, A. (2008). New Issues in Islamic Finance and Economics: Progress and Challenges, John Wiley & Sons (Asia).

Askari, H., Iqbal, Z., and Mirakhor, A. (2010). Globalization and Islamic Finance: Convergence, Prospects and Challenges, John Wiley & Sons (Asia).

Abdullah, D. V. and Chee, K. (2010). Islamic Finance, Why it Makes Sense, Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Pte Ltd.

Bakar, D. and Engku Ali, E. R. A. (2008). Essential Readings in Islamic Finance. Kuala Lumpur: CERT.

Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) (2010). Shariah Governance Framework for Islamic Financial Institutions. Available at http://www.bnm.gov.my. Accessed on 1st October 2014.

Brown, D. (1996). Rethinking Tradition in Modern Islamic Thought, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

IFSB. (2006). Guiding Principles on Corporate Governance for Institutions Offering Only Islamic Financial Services (Excluding Islamic Insurance (Takaful) Institutions and Islamic Mutual Funds. Kuala Lumpur: IFSB.

IFSB. (2008). Survey on Shari ah Boards of Institutions Offering Islamic Financial Services Across Jurisdictions. Kuala Lumpur: IFSB.

IFSB (2009). Guiding Principles on Shari ah Governance System in Institutions Offering Islamic Financial Services. Kuala Lumpur: IFSB.

Igbal, Z, & Mirakhor, A. (2004). Stakeholders Model of Governance in Islamic Economic System. Islamic Economic Studies. Volume 11, No. 2, 43-64.

Iqbal, Z, & Mirakhor, A. (2007). An Introduction to Islamic Finance: Theory and Practice. Singapore: John Wiley and Sons (Asia) Pte. Ltd.

Kahf, M. (2004). Islamic Banks: The Rise of a New Power Alliance of Wealth and Sharia’ Scholars. In Clement M. Henry &Rodney Wilson, (Eds.), (2004), The Politics of Islamic Finance, 17-36. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Ltd.

Kahf, M. (1978). The Islamic Economy. Plainfield: Muslim Student Association (US-Canada).

Kramer, G. (1977) “Islamist Notions of Democracy,” in Joel Beinin and Joe Stork (eds.), Political Islam: Essays from Middle East Report (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press), p. 77.

Michel Galloux, Finance Islamique et pouvoir politique: le cas de l’Egypte moderne (Paris: Presscy Universitaires de France, 1997), pp. 39-45.

McMillen, M. J. T. (2006). Islamic Capital Markets: Developments and Issues. Capital Markets Law Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2, 136-172.

Mortimer, E. (1982). Faith and Power: The Politics of Islam. New York: Random House, p. 123.

Muhammad, A. (2007). Understanding Islamic Finance, Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia).

Nathan, S. & Ribiere, V. (2007). From Knowledge To Wisdom: The Case Of Corporate Governance In Islamic Banking. The Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, Vol. 37, Issue 4, 471-483. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Okeahalam, C. C. (1998). The Political Economy of Bank Failure-and Supervision in the Republic of South Africa: African Journal of Political Science, 3, No. 2,.29-118.

Rammal, H. G. (Spring 2006). The Importance of Shariah Supervision in IFIs. Corporate Ownership and Control, Vol. 3, Issue 3, 204-208.

Usmani, Muhammad Taqi, Sukuk and their Contemporary Applications, Bahrain: AAOIFI, 2007.

Warde, I. (1998). The Role of Shariah Boards: A Survey, IBPC Working Papers (San Francisco, CA: IBPC).

Warde, I. (1997). “Comparing the Profitability of Islamic and Conventional Banks,” IBPC Working Papers (San Francisco, CA: IBPC).

Warde, I (2010). Islamic Finance in the Global Economy, 2nd Edition, Edinburgh University Press.

Yaacob, H. (2010). The New Central Bank of Malaysia Act 2009 (Act701): Enhancing the Integrity and Role of the Shariah Advisory Council (SAC) in Islamic Finance, Research Paper (No: 6/2010), ISRA.

[1] Opinions of scholars.