By Michael Raska

This Middle East Insight is available for download Insight 26 Raska

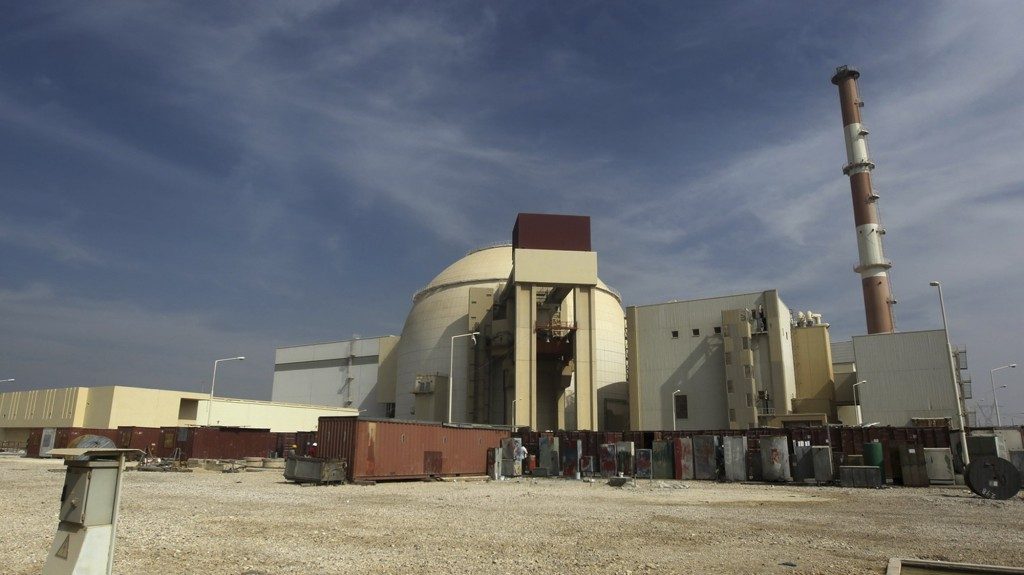

It also appeared in the Straits Times Review on 31 May 2011. Throughout the Cold War, Israel had been able to prevent nuclear proliferation in the Middle East. Its policy of nuclear opacity never admitting the possession of nuclear weapons, albeit not denying them either has served at the core of Israel’s deterrence. In 1981, after Israel’s annihilation of the Iraqi nuclear reactor Osirak at Tuwaitha, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin proclaimed that: under no circumstances would we [Israel] allow the enemy to develop weapons of mass destruction against our nation. We will defend Israel’s citizens, in time, with all the means at our disposal. Under the so-called Begin Doctrine, Israel would not allow itself to be the second country to introduce nuclear weapons in the Middle East. A quarter of a century later, the viability of the Begin Doctrine as much as Israel’s entire policy of nuclear opacity is on the verge of another test. For nearly a decade now, Iran has been defying international diplomatic pressures while vehemently denying developing nuclear (weapons) capability. Notwithstanding the contending intelligence assessments on the actual point of no return when Iran would de facto cross a particular technological threshold, the prospect of a nuclear Iran opens the Pandora’s Box of nuclear proliferation in the Middle East. From an Israeli perspective, the essence of the Iranian threat, relevant not only for Israel, is the increasing convergence between radical ideology, long-range missile capability, and nuclear weapons. Concerns over Iran’s covert efforts to develop its nuclear weapon capability, a claim that Tehran denies, have been amplified by the development of its medium-range ballistic missile programs, and its open calls for Israel’s destruction. Iranian efforts to develop nuclear capability may have also ignited fears in neighboring states; Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Turkey have announced plans to start their own civilian nuclear programs under the auspices of the IAEA. Some of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have also inked deals with other countries and companies for setting up facilities for nuclear energy production. At the end of 2008, for example, the GCC authorized nuclear development for its Gulf members. The United Arab Emirates plans to build four nuclear energy plants in its western region, and the first plant is expected to be completed by 2017. More importantly, however, a nuclear Iran could embolden terrorist groups and organizations into acting more aggressively vis-├á-vis Israel. The sum of all fears is the possible nexus of two factors Iran providing a nuclear umbrella to its terror proxies such as Hizballah and deliberately threatening Israel’s destruction. The fundamental question is what is Israel prepared to do in response? Israel’s Strategic Options If Iran indeed goes nuclear, Israel may no longer be able to sustain its ambiguous policy of nuclear opacity and would have to rethink its nuclear doctrine. Depending on the complexity and modalities of the Iranian nuclear introduction, Israeli policy makers will have to move beyond the simple dichotomy of the bomb in the basement versus the bomb on the table debate. Israel will have to decide when, how, and how much to disclose in order to maximize its nuclear deterrent. Theoretically, in the process of configuring the modalities of the use of Israel’s nuclear arsenal, Israeli policy-makers will have to consider at least four options or scenarios in reviewing its nuclear doctrine: (1) Israel maintains a status-quo by keeping its nuclear opacity intact. Israel may opt for a flexible response by keeping the foundations of its nuclear ambiguity intact. In other words, Israel’s nuclear capabilities, protective efforts, and its nuclear doctrine may remain undisclosed, albeit not denied either, and Israel would continue to signal its willingness and ability to deliver an appropriate destructive response. However, from an Israeli perspective, such posturing may lower the enemy state’s perceptions of Israel’s nuclear deterrent, and increase the risks for a preemptive nuclear strike. (2) Israel accepts nuclear parity, shifts to a declaratory status based on Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). Israel declares a ready arsenal (launch-on warning); a second-strike nuclear capability; and devises a nuclear war-fighting doctrine. Israel may switch to an open nuclear posture, yet, with multiple options of disclosure to maximize gains for Israeli nuclear requirements. (3) Israel shifts to a policy of a minimum credible deterrence in the form of a recessed deterrence no first use/second strike capability. Israel can opt for a policy of minimum credible deterrence in case Iran or any other Arab state in the Middle East does not overtly test a nuclear weapon nor openly discloses its nuclear arsenal. Following the Indian model, Israel’s nuclear doctrine would then underline a policy of no first use; however, its nuclear configuration would have to guarantee a sufficient capability for a second-strike that would cause unacceptable damage to the enemy. Given Israel’s geostrategic constraints, however, this option would invite an increasing risk for an enemy’s preemptive first strike on Israel, assuming that Israel cannot trade space for time, nor could she afford to lose a single city. Furthermore, ensuring the survivability of Israel’s assets to a potential strike would have to be guaranteed. Therefore, this option seems unlikely to maximize Israel’s nuclear advantage. (4) Israel resorts to international arms control regime or pursues denuclearization of the Middle East. Israel may rethink the possibility of negotiating regional arms-control talks, and supporting a WMD-free Middle East. From the Israeli perspective, however, this option seems unlikely in the absence of a comprehensive peace with Arab countries and Iran. Furthermore, Iran would have to renounce its nuclear programs in conjunction with the dismantlement of Egypt, Syria and Saudi Arabia’s chemical and biological weapons programs. The Use of Force With Iran going nuclear, Israeli policymakers will be determined, perhaps more than ever, to prevent Iran or any other neighboring Arab state from acquiring nuclear weapons. On 6 September 2007, Israel conducted a secret precision strike on Syria on what Israeli and US intelligence analysts judged as a partly constructed Syrian nuclear facility, apparently modelled on North Korea’s design. While intelligence estimates indicated that the Syrian facility was years from completion, the timing of the attack showed that Israel is determined to neutralize even a nascent nuclear project in a neighboring state. Yet a potential Israeli preventive air strike on selected Iranian nuclear installations would engender much greater difficulties. Iran has spread out its nuclear facilities and constructed the bulk of their nuclear complex underground to protect it from conventional air strikes. Israeli strategists must also calculate additional risks: (1) the distance of flying either over Arab or Turkish airspace to reach their targets; (2) the potential collateral damage stemming from possible nuclear radiation and contamination of the targeted area; (3) upgraded Iranian air defences with Russian-made Tor-M1 air defence systems; and (4) the probability and consequences of Iranian retaliation such as interfering with the flow of oil from the Persian Gulf, launching counter-attacks with conventional ballistic missiles against Israel, and mobilizing its network of terrorist organizations such Hizballah or Hamas. Based on Israeli threat perceptions and historical experience, Israel may have no choice but to deny its enemies the capability to develop nuclear weapons. As Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak said, the prevailing lesson from Israel’s war experience has been the belief that ultimately we [Israel] are standing alone. This belief may essentially continue to drive Israel’s strategic choices. One of the contending views within the Israeli political-military establishment is that while preventive military action vis-a-vis Iran would inevitably carry considerable political and operational risks, inaction may yield far worse consequences. To avoid the path, the international community must ensure that the Pandora’s Box of nuclear proliferation in the Middle East remains closed.

Michael Raska is a PhD candidate at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, completing his dissertation on the dynamics of military change and innovation in Israel and South Korea. His publications have focused on defense transformation and strategic developments in East Asia and the Middle East. He holds a M.A. degree in International Studies from the Graduate School of International Studies, Yonsei University, B.A. in International Communications and International Studies (summa cum laude) from the Missouri Southern State University. He has diverse research experience as a visiting research fellow at several institutions, including the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Pacific Forum CSIS, Samsung Economic Research Institute, and Delegation of the European Commission to the ROK. He can be reached at michaelraska@nus.edu.sg.