With Europe and Asia growing closer, particularly through economic integration, it is no longer sufficient to see Iran as a Middle Eastern nation. This series of Insights will examine Iran’s bilateral relations from a Eurasian perspective, drawing out the understudied and underappreciated economic and political considerations that increasingly shape the Islamic Republic’s conception of its place in the international system and the power it is able to exercise in that system. This research project is a collaboration between MEI and Bourse & Bazaar, an Iran-focused business media company based in London.

Thanks to its geographical position and its positive and constructive relationship with China, Iran has a potentially pivotal role within Beijing’s Eurasian projection. However, the US administration’s decision to reimpose secondary sanctions on Iran seems to have slowed down the country’s integration into the emerging Eurasian architecture, causing Tehran to reprioritise bilateral relations with Beijing. This article argues that to mitigate the power imbalance in its relations with China, Iran should keep pushing for integration into China’s Belt and Road Initiative and lobbying for full membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organistion. Ultimately, Sino–Iranian relations should be the flywheel for Iran’s participation in China-led Eurasian multilateral projects.

CLICK HERE FOR THE PDF.

By Jacopo Scita

In January 2016, Chinese President Xi Jinping embarked on a trip that took him through three Middle Eastern capitals — Riyadh, Cairo and, finally, Tehran for a day. The timing of Xi’s first visit to the region did not look fortuitous. Indeed, it happened less than a week after the official implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the landmark agreement capping the 12 years of complex negotiations to settle the Iran nuclear issue. Beijing’s mediatory role in the nuclear talks with Iran was decisive.[1] In this light, the January 2016 visit was evidently the occasion for Beijing to reassure, and renew its commitments towards, its partners in a region that is becoming increasingly central to China’s geopolitical ambitions.

While Sino–Iranian relations are often looked at through the lens of Beijing’s voracious demand for oil or the enduring competition between China and the United States, Iran has a clear role in Beijing’s Eurasian projection — a system of economic, infrastructural and institutional connections that links China with Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe. However, in order to gain the maximum benefit from this emerging inter-regional order, Tehran should push to become fully integrated into the institutional, economic and infrastructural architectures that China, both alone and in concert with Russia and the other regional powers, has been developing to strengthen its westward projection. In short, Iran’s main goal in the medium to long term should be to leverage its positive relationship with China to consolidate its pivotal position in the emerging Eurasian order.

This article looks at the state of Sino–Iranian bilateral relations as the foundation for Tehran’s opportunity to increase its integration into China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). Along with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the BRI and the SCO represent, on different levels, the most important expressions of the Chinese-led Eurasian order. Iran’s still-limited place in these projects appears to be a consequence of the abrupt interruption of the normalisation path opened up by the JCPOA.

The State of Sino–Iranian Relations

President Xi’s 2016 visit to Tehran resulted in the signing of the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) between China and Iran. CSPs are the highest level in the spectrum of partnerships in China’s foreign policy strategy. In the Persian Gulf, only Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Iran enjoy this framework of co-operation with Beijing. Enlarging the picture to the whole Middle East and North African region, the only additions to this exclusive club are Algeria and Egypt.[2] Therefore, the 2016 meeting between President Xi and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani marked the official recognition of Iran as a crucial partner for China. On the occasion, 17 memorandums of understanding on areas ranging from the Silk Road to infrastructural, scientific and cultural co-operation were signed by the two governments.[3] The establishment of the CSP came as the confirmation of both a historical trend, as well as the recognition of a new set of opportunities offered by the JCPOA.

Diplomatic relations between China and Iran, established when China was admitted into the United Nations in 1971, survived the 1979 Iranian revolution. To some extent, Iran’s international isolation following the establishment of the Islamic Republic increased the mutual interest in co-operating. Indeed, China progressively became one of Iran’s most important and consistent foreign partners. In the aftermath of the Iraq–Iran war, Tehran found in Beijing a partner keen to participate in the reconstruction of the country. This paved the way for a sustained campaign of multidimensional Chinese infrastructural investments in the country.[4] However, the scope of co-operation has never been limited to infrastructure development. In fact, during the past 40 years of bilateral relations, China and Iran have established a multisectoral co-operation, ranging from Beijing’s crucial assistance in/with Tehran’s nuclear programme to its transfer of scientific expertise and military technology.[5] Despite some periodic backlashes, Sino–Iranian relations have been remarkably consistent over the years. However, when UN Security Council sanctions against Iran’s nuclear programme isolated the country, Iran’s dependence on China as an economic lifeline grew quickly. The result was a substantial reduction of Iran’s agency, with China in a position to “dictate the rules of the game”.[6]

The JCPOA’s negotiations — whose final and decisive round coincided with the rise to power of Xi and the launch of the BRI — and its subsequent implementation appeared to be a breakthrough in Sino–Iranian relations. For Iran, the end of international sanctions would have meant the possibility of rebalancing its position vis-à-vis Beijing. For China, a substantial decrease in the risk of escalation in the Persian Gulf and the end of Iran’s international isolation would have benefitted its westward ambitions. However, the election of Donald Trump as the 45th US president and the subsequent US withdrawal from the JCPOA abruptly interrupted Iran’s renewed ambitions. Despite China — along with the other signatories — remaining committed to and supportive of the JCPOA, Washington’s re-imposition of secondary sanctions in November 2018 significantly jeopardised the scope of the deal. Although Beijing continues to buy Iranian oil in defiance of US sanctions,[7] offering Tehran a lifeline, the current spiral of tensions has inflicted a major blow to Iran’s ability to relaunch its partnership with China along the more balanced lines anticipated by the CSP.

Indeed, the fundamental feature of Sino–Iranian relations is the power imbalance that is typical of any great power–middle power partnership.[8] Iran’s international isolation has proved to increase this power asymmetry, creating dangerous phases of economic overdependence on China. The opportunity to mitigate Iran’s overdependence on China could come from the progressive inclusion of Iran within the Chinese-led Eurasian integration projects. In other words, Tehran’s agency vis-à-vis Beijing will grow only if Iran is able, and will be allowed, to occupy its pivotal place along the New Silk Road and successfully claim a full membership seat in the SCO.

Iran and the BRI: Claiming Tehran’s Pivotal Position

Undoubtedly, the BRI represents one of the most ambitious geopolitical, infrastructural and economic projects of the 21st century. Launched in 2013 by Xi, the project quickly became the new Chinese leadership’s global blueprint. The ambitions underlying the BRI have never been hidden. According to the official Chinese vision, “the initiative aims to promote orderly and free flow of economic factors, highly efficient allocation of resources and deep integration of markets by enhancing connectivity of Asian, European and African continents and their adjacent areas”.[9]

Within the BRI project, Iran occupies a pivotal position. Tehran is one of the main hubs of the China–Central Asia–West Asia Economic Corridor, one of the routes that form the web of land links in the New Silk Road. In particular, the West Asia Economic Corridor has strong strategic relevance in itself because it allows China to reach the warm waters of the Mediterranean Sea without passing through Russia.[10] The strategic location of Iran is even more evident, considering the country’s potential to become China’s access door to the entire Middle Eastern market. All things considered, by including Iran in the emerging Eurasian order, China will achieve a stronger regional position, while promoting its alternative, more comprehensive view of global affairs. The exclusion of Iran from this order would mean excluding a country that is located at the historical, geographical and economic centre of Eurasia. Such an option appears highly counterproductive for an actor that is shaping its leadership position in the region and building a westward strategy which has Eurasia at its centre.

Having said that, it should not come as a surprise that, on the occasion of the launch of the CSP, Xi reframed the relationship between China and Iran as part of the multilateral vision developed by the BRI framework.[11] This vision appears to have been well received by Iranian officials. For instance, during his last visit to China in August 2019, Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif reiterated that the BRI helped to enhance mutual trust between China and Iran, suggesting that the initiative is a “manifestation of the fact that the two countries’ co-operation is now entering a new phase”.[12] What appears clear, then, is that the BRI has the potential to redefine the framework of co-operation between China and Iran. However, this enormous potential is still largely unexpressed.

Despite its economic power and geopolitical ambitions, China has not been able to realise its BRI agenda quickly enough, in part because its attention has been diverted by its ongoing trade war with the United States. Beijing’s score in delivering large BRI infrastructural projects remains mixed. For instance, while the first freight trains from China reached the United Kingdom in 2017, passing through Kazakhstan in Central Asia,[13] several Asian countries are experiencing delays in the delivery of BRI-related infrastructural projects.[14] Furthermore, the countries and regions that the BRI aims to connect are undergoing a considerably high level of political tensions. While the Chinese strategy of offering loans and investments to pave the way for its geopolitical project is attractive, local tensions in some places have been reoriented towards China, which could lead to some of China’s infrastructure projects stalling.[15] Given this situation, it seems that the full inclusion of Iran in the BRI has been slowed down. And, the pressure of secondary sanctions on Iran will only further delay the process.

In these circumstances, Tehran’s agency in its relationship with China appears to remain limited. However, Iran’s pivotal positioning in China’s westward projection is stable. Acknowledging this reality and attuning policymaking to it is a necessary first step. In this regard, Iran should focus on developing “policy coordination, promotion of free trade, people to people interaction [and] financial integration”[16] with China to effectively extend the scope of the BRI beyond infrastructural development. If Iran is successful in creating an environment that expands and favours sustained, wide-ranging co-operation with China, this is likely to have a positive impact even on Tehran’s full integration into the SCO.

The SCO: Institutionalising Iran’s place in Eurasia

The SCO was founded in 2001 as the continuation of the Shanghai Five, a Chinese-led organisation aimed at addressing cross-border issues. With the launch of the US-led global war on terror and the presence of US troops in Afghanistan, Beijing and Moscow, the two main members of the original Shanghai Five, recognised the security potential of a more institutionalised regional organisation.[17] The founding declaration of the SCO, however, carries a broader series of goals, ranging from regional peace and stability and strengthening mutual trust to pursuing multisectoral co-operation among the members.[18] Therefore, it appears clear that, since its establishment, the SCO has had ambitions of opening a path for economic integration between China, Russia and the four Central Asian republics. In 2017, India and Pakistan were admitted as members of the organisation, marking a spectacular expansion of the SCO. As Russian President Vladimir Putin noted during the 2018 Qingdao Summit, the organisation comprises “one fourth of the world’s GDP, 43 per cent of the international population and 23 per cent of global territory”.[19]

Iran obtained observer status in the SCO in 2005 and has officially applied for full membership. As extensively described by Shahram Akbarzadeh, Iran’s push for full integration into the organisation was a distinctive geostrategic priority of the Ahmadinejad government.[20] This position was mainly built on the idea that the SCO was a counterweight to and bulwark against US attempts to strength its position in Central and East Asia. It is worth noting that Ahmadinejad’s era was that of the “Sinicisation” of the Iranian domestic market — a forced consequence of international sanctions but also an attempt to distance Iran from the West while favouring its eastward projection.[21] However, the troubled domestic and international image of the Ahmadinejad presidency did not appeal to SCO members, which froze Iran’s application in accordance with an organisation rule that blocks the admission of countries under UN sanctions.[22]

The election of Hassan Rouhani as successor to Ahmadinejad marked an important shift in Tehran’s strategic priorities. Indeed, the new government reprioritised dialogue with the West and, in particular, with the European Union. As Kaveh Afrasiabi and Seyedrasoul Mousavi write, the Rouhani administration adopted a more nuanced “both East and West” strategy.[23] To some extent, this shift — along with the administration’s strong focus on the JCPOA negotiations — detracted from Iran’s lobbying effort to obtain full SCO membership. However, since the Trump administration hardened America’s Iran policy, Tehran seems to have renewed its interest in the organisation, considering the SCO an example of multilateralism in contrast to Washington’s unilateralism.[24] However, notwithstanding both China and Russia’s apparent commitment to promoting Iran’s full membership,[25] the process remains stuck.

Despite clear differences, Ahmadinejad and Rouhani’s approaches to the SCO show a constant. So far, it appears that Iran’s seesawing interest in the organisation is due to external push factors. However, even as international isolation has pushed Tehran towards its Eastern partners, the country has prioritised its bilateral relations with China and, to a lesser extent, Russia. Although this position reflects the short-term necessity of establishing more solid economic and political lifelines, in the medium and long terms, Iran should re-centre its posture towards the SCO’s pull factors. Indeed, the organisation offers a framework of institutionalised co-operation that, arguably, will constitute the backbone of future Eurasian governance. Furthermore, as pointed out by Jonathan Fulton, Iran’s full membership in the SCO could have a domino effect, enticing other Middle Eastern countries into the organisation, which could put Iran in the driver’s seat of the SCO’s westward expansion.[26] In the best-case scenario, this could offer a further platform for institutionalised dialogue between Tehran and the other Persian Gulf countries.

Conclusion

Relations between China and Iran are often understood as a function of the China–US–Iran triangle or of Beijing’s energy security strategy. Despite both these elements being part of the complex reality that characterises the Sino–Iranian partnership, China’s growing westward ambitions have shown that Iran could have a pivotal position in the future of Eurasia. Indeed, looking East is not only “an opportunity for an alternative future and trajectory [and] a shortcut to prosperity”[27] but also represents for Iran the possibility of gaining renewed political and economic centrality. Iran’s good relationship with Beijing could function as a flywheel to increase the country’s level of integration in the emerging Chinese-led Eurasian order. Even though the US withdrawal from the JCPOA has undermined the positive momentum that was emerging in 2016, Iran should keep working to obtain full membership in the SCO. Indeed, Iran’s renewed international isolation consequent to Washington’s stepped up “maximum pressure” campaign — which is likely to increase in intensity if the JCPOA falls apart without an alternative agreement in place — is again pushing Iran towards China. As was the case before the JCPOA, China will once again be in the position of dictating the rules of the game to Tehran. Therefore, lobbying for greater integration into the Eurasian multilateral order is one of Iran’s best options to mitigate the imbalance of power in its current bilateral relations with China. At the same time, the growing Chinese interest in the Persian Gulf and the development of the BRI may create a new platform of economic opportunities, infrastructural integration and dialogue that could eventually promote the emergence of an alternative security architecture involving Iran and its neighbours.

About the Author

Mr Jacopo Scita is a HH Sheikh Nasser al-Mohammad al-Sabah doctoral fellow at the School of Government and International Affairs, Durham University. His doctoral project explores the evolution of China’s role vis-à-vis Iran from the 1979 Revolution to the 2015 JCPOA.

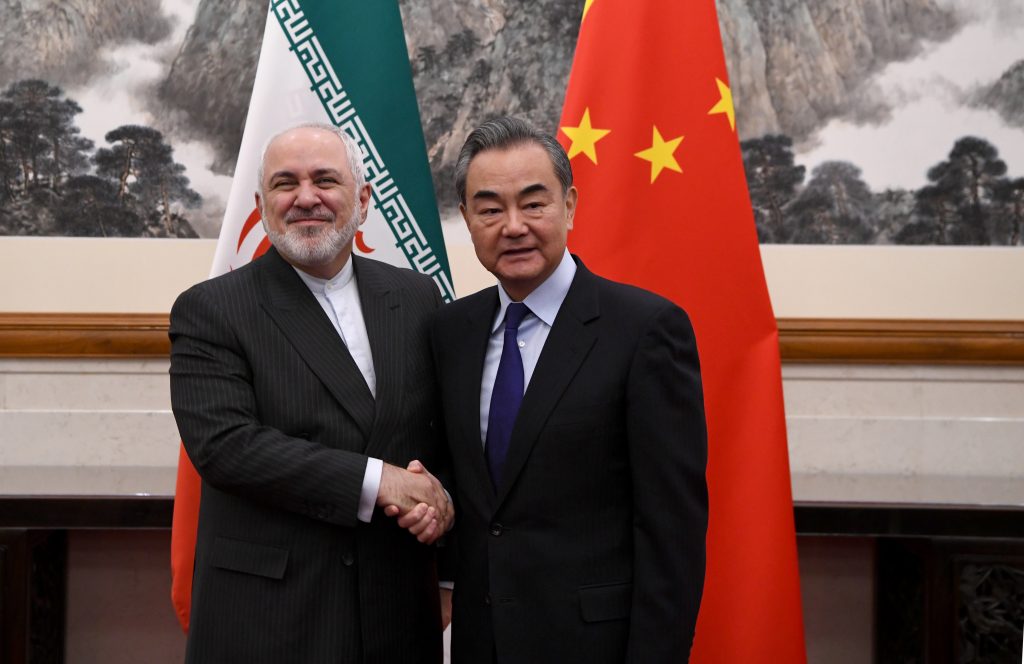

Image caption: Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi shakes hands with Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif during their meeting at the Diaoyutai State Guest House on 31 December 2019 in Beijing, China. Photo: Noel Celis/Pool/AFP.

Footnotes

[1] John W Garver, “China and Iran Nuclear Negotiations: Beijing Mediation Effort”, in The Red Star & the Crescent: China and the Middle East, ed J Reardon-Anderson (London: Hurst & Co, 2018).

[2] Jonathan Fulton, “China’s changing role in the Middle East”, Atlantic Council, 5 June 2019, 3–4, https://atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/china-s-changing-role-in-the-middle-east-2/.

[3] “Iran, China sign 17 documents, MoUs”, Official Website of the President of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 23 January 2016, http://president.ir/en/91427.

[4] John Calabrese, “China and Iran: Mismatched Partner”, Jamestown Foundation, August 2006, https://jamestown.org/wp-content/uploads/2006/08/Jamestown-ChinaIranMismatch_01.pdf?x52813; and Scott W Harold and Alireza Nader, “China and Iran. Economic, Political, and Military Relations”, RAND (2012), https://www.rand.org/pubs/occasional_papers/OP351.html.

[5] See Calabrese, “China and Iran”, and John W Garver, China & Iran: Ancient Partners in a Post-Imperial World (University of Washington Press: 2006).

[6] Anoush Ehteshami et al, “Chinese–Iranian mutual strategic perceptions”, The China Journal, 79 (2018): 6–7.

[7] “Iran’s oil export claims not without foundations says Tankertrackers.com”, bne Intellinews, 2 December 2019, https://www.intellinews.com/iran-s-oil-export-claims-not-without-foundation-says-tankertrackers-com-172638/.

[8] Dara Conduit and Shahram Akbarzadeh, “Great Power–Middle Power Dynamics: The Case of China and Iran”, Journal of Contemporary China, 28 (2019).

[9] “China unveils action plan on Belt and Road Initiative”, China Daily, 28 March 2015, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2015-03/28/content_19938124.htm.

[10] Thomas Erdbrink, “For China’s global ambitions, ‘Iran is at the center of everything’”, The New York Times, 25 July 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/25/world/middleeast/iran-china-business-ties.html.

[11] “Full text of Xi’s signed article on Iranian newspaper”, China Daily, 21 January 2016, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/world/2016xivisitmiddleeast/2016-01/21/content_23189585.htm.

[12] “FM Zarif says shared vision binds Iran-China relations”, Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA), 25 August 2019, https://en.irna.ir/news/83450928/FM-Zarif-says-shared-vision-binds-Iran-China-relations.

[13] “First freight train from China arrives in London”, BBC News, 18 January 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/av/uk-38667988/first-freight-train-from-china-arrives-in-london.

[14] See Tamara Vaal, “Kazakh president orders investigation into China-linked transport project”, Reuters, 8 October 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kazakhstan-president-railway-probe/kazakh-president-orders-investigation-into-china-linked-transport-project-idUSKBN1WN1CC; Kosh Raj Koirala, “Nepal–China railway plans hit a dead end”, Asia Times, 18 July 2019, https://asiatimes.com/2019/07/nepal-china-railway-plans-hit-a-dead-end/; Go Yamada and Stefania Palma, “Is China’s Belt and Road Initiative working? A progress report from eight countries”, Nikkei Asian Review, 28 March 2018, https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Cover-Story/Is-China-s-Belt-and-Road-working-A-progress-report-from-eight-countries.

[15] Bradley Jardine, “Why are there anti-China protests in Central Asia?”, The Washington Post, 16 October 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/10/16/why-are-there-anti-china-protests-central-asia/.

[16] Mohsen Shariatinia and Hamidreza Azizi, “Iran–China Cooperation in the Silk Road Economic Belt: From Strategic Understanding to Operational Understanding”, China & World Economy, 25, no. 5 (2017): 58.

[17] Shahram Akbarzadeh, “Iran and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation: Ideology and Realpolitik in Iranian Foreign Policy”, Australian Journal of International Affairs, (2014): 3, doi: 10.1080/10357718.2014.934195.

[18] “Shanghai Declaration on the Establishment of the SCO”, Official Website of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, 2001, http://eng.sectsco.org/documents/.

[19] “Putin: SCO could achieve bigger goals”, China News Service, 6 June 2018, http://www.ecns.cn/news/politics/2018-06-06/detail-ifyuyvzv3223815.shtml.

[20] Akbarzadeh, “Iran”, 8.

[21] See Ehteshami et al, “Chinese–Iranian”.

[22] Jiao Wu and Xiaokun Li, “SCO agrees deal to expand”, China Daily, 12 June 2010, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/cndy/2010-06/12/content_9968565.htm.

[23] Kaveh Afrasiabi and Seyedrasoul Mousavi, “A Power Shift To The East: Iran and the SCO”, LobeLog, 7 June 2017, https://lobelog.com/a-power-shift-to-the-east-iran-and-the-sco/.

[24] See “Iran urges SCO states to promote multilateralism”, Financial Tribune, 1 November 2019, https://financialtribune.com/articles/national/100566/iran-urges-sco-states-to-promote-multilateralism; and Pepe Escobar, “Iran at the center of Eurasian riddle”, Asia Times, 17 June 2019, https://asiatimes.com/2019/06/iran-at-the-center-of-the-eurasian-riddle/.

[25] See “Xi Jinping meets with President Hassan Rouhani of Iran”, Embassy of the PRC in the USA, 14 June 2019, http://www.china-embassy.org/eng/zgyw/t1673196.htm; and “Rouhani: More dialogue needed with Russia after US nuclear deal exit”, Tehran Times, 9 June 2018, https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/424283/Rouhani-More-dialogue-needed-with-Russia-after-U-S-nuclear.

[26] Jonathan Fulton, “Could the SCO expand into the Middle East?”, The Diplomat, 24 February 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/02/could-the-sco-expand-into-the-middle-east/.

[27] Anoushiravan Ehteshami and Gawdat Bahgat, “Iran’s Asianisation Strategy”, in Iran Looking East: An Alternative to the EU? ed. Annalisa Perteghella, (Milan: Italian Institute for International Political Studies, 2019).