Following the 1948 war and until the 1967 war, Jerusalem was divided between Jordan and Israel. During this period, each of the two cities changed demographically and geographically. This article [1] captures the major changes in those respects. It also compares the political and social changes and the development policies implemented by the two governments, including how the two sides of the city were integrated into the national policies of their respective states.

CLICK HERE FOR THE PDF.

By Menachem Klein

The 1948 Arab−Israeli war ended on 30 November, when Israel and Jordan agreed to a ceasefire. Later, on 3 April 1949, the two countries signed an armistice. Based on their pre-war cooperation, the two countries preferred to divide Jerusalem between themselves rather than accept the United Nations’ corpus separatum (separate entity) proposal, which would have left them no hold in the city as Jerusalem would have been internationalised.

The war left Jordanian and Israeli Jerusalemites with mixed feelings towards their city. They had just endured a traumatic experience, which cut the city along ethno-national lines. No Israeli Jew remained on the Jordanian side and very few Palestinians lived on the Israeli side. Many among these Jerusalamites remembered their pre-1948 joint urban space. Both publics tried to adjust to the dramatic geographical, political and social changes that the war had created, including the challenge of absorbing huge numbers of refugees and immigrants.

Meanwhile, municipal instability prevailed on each side. Sharp political struggles among the players who made up the city council on the Israeli side drove the Israeli government to dissolve the council in April 1955. Stability was achieved only after the July 1955 municipal elections. On the Jordanian side, a series of conflicts since 1951 between the mayor, ‘Aref al-‘Aref, and the government in Amman led to the latter discharging the mayor. Two persons, each for a short time, and a managing committee led the municipality thereafter. Stability was achieved only in 1957, when the government appointed a new mayor, who remained in office until the Israeli occupation in 1967.

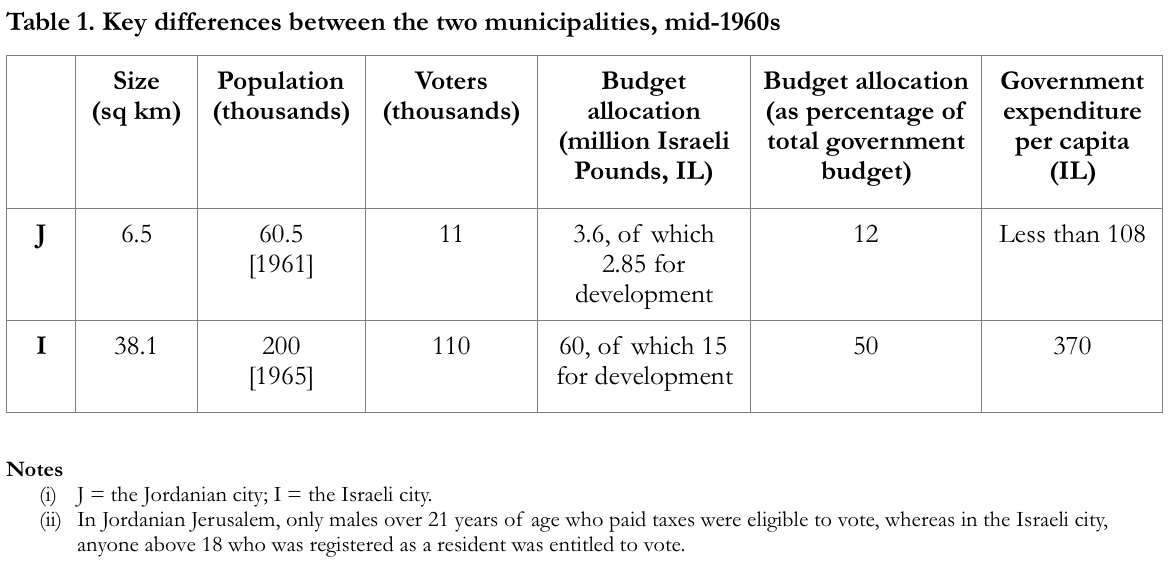

The comparative socioeconomic data I present below for the period between the mid-1950s and June 1967 show that, although the two municipality buildings in Jerusalem were separated by just some 100 metres, they represented two vastly different cities and two different sets of central government–municipality relations. On the Jordanian side, the government heavily limited Jerusalem’s development and closely controlled the municipality’s decisions. On the Israeli side, however, the government invested sizeable resources to develop what was to become its capital.

Jordanian and Israeli Cities: An Overview

Table 1 captures the huge differences between the two cities in terms of size, population, government outlay and local municipal resources.

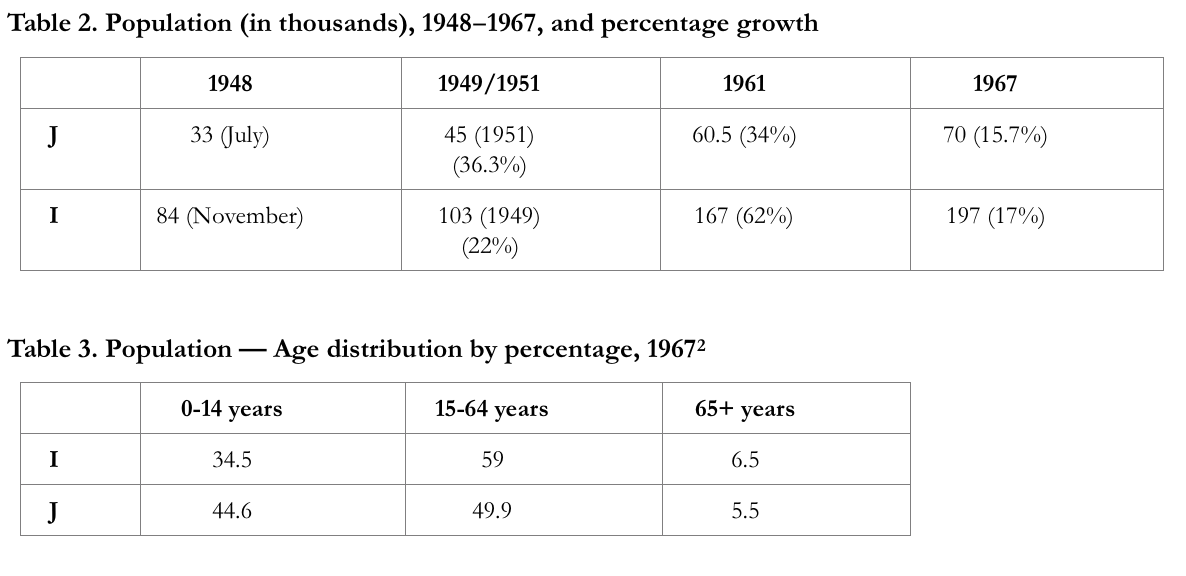

Table 2 shows the population growth in the two cities between 1948 and 1967. Jewish immigrants from abroad constituted the main source of population growth in Israeli Jerusalem, whereas, in Jordanian Jerusalem, the newcomers to the city were locals, refugees of the 1948 war and Hebronites. Jordanian Jerusalem had more young persons than its Israeli counterpart (see Table 3).

Sociopolitical Profile

In terms of origins, in mid-1964, 50 per cent of the population of Israeli Jerusalem were born in Israel or Mandatory Palestine, 25 per cent in Asian and African countries, and 25 per cent in Europe, mostly in eastern Europe. Among those who were born in Israel or Mandatory Palestine, 45 per cent had their ancestral origins in Asian and African countries while 38 per cent had ancestors who came from Europe. In other words, the early 1950s immigrants to Israeli Jerusalem changed the balance between western and Arab Jews in favour of the latter. Given the influx of immigrants and the fact that 34.5 per cent of the population were aged 14 years or below in 1967 (see Table 3), a sizeable number of Israeli Jerusalemites by then had no experience of the shared city that Jerusalem was prior to 1948 [3]. But the core neighbourhoods (eg Rehavia, Beit Hakerem, Nahlaot) were populated by pre-1948 Jerusalemites affiliated with local and national institutions. The old Ashkenazi elite in Israeli Jerusalem prevented newcomers to the city from holding leading positions. They patronised the immigrants and governed them through veteran and newcomer Arab Jew collaborators.

The demographic shift in Israeli Jerusalem would lead, in the 1970s, to the fall of the Labour movement. The Labour-led Israeli government put in transit camps the large number of immigrants it had brought into the country in the early 1950s. About 10,000 people lived in such a camp in south Jerusalem. Later, Israel relocated them to neighbourhoods along the armistice line [4], where they suffered discrimination and were fully dependent on the ruling Ashkenazi establishment.

In Jordanian Jerusalem, most of the population — 36,800 persons — lived in the Old City in 1961, with just 23,600 living outside it. The 1948 war, followed by the Jordanian annexation of the West Bank two years later, terminated the rule of the old clan- and wealth-based elite. While the Palestinian nationalist elite who opposed the annexation struggled against the Hashemites, the middle and lower classes enjoyed social mobility as the Jordanian regime encouraged those in Hebron who supported it to move to East Jerusalem.

While Israel gradually moved its government offices to Jerusalem and invested in its development, Jordan kept its side of Jerusalem underdeveloped. In 1950, Jordan began empowering Amman at Jerusalem’s expense by, among other things, transferring its central government departments in Jerusalem to its emerging capital. This move drew complaints and protests from local leaders in East Jerusalem but to no avail. Later, when Israel moved its capital to Jerusalem in July 1953, Jordan declared that it did not consider matching the move; it merely opened in Jerusalem branches of its Economic Affairs, Construction, Education, Justice and Transport ministries. Given the declining opportunities in Jerusalem owing to Jordan’s neglect, educated Jerusalemites emigrated to Amman. This exit as well as the aforementioned immigration of Hebronites to East Jerusalem meant that, by 1967, only 26,000 people in Jordanian Jerusalem were original Jerusalemites; 67 per cent of the residents of the Old City and 95 per cent of those of Abu Tor to the south of the Old City came from Hebron. Hebronites dominated the waqf (religious endowment) in East Jerusalem, the Shari’a courts, the Bureau of Commerce and the city council. Out of eight Jerusalem district governors, only one — Anwar Nusseibeh — was a member of the local elite. The percentage of businesses in East Jerusalem owned by those who came from Hebron rose from 36 in 1950 to 40.8 by 1960.

Economy and Living Standards

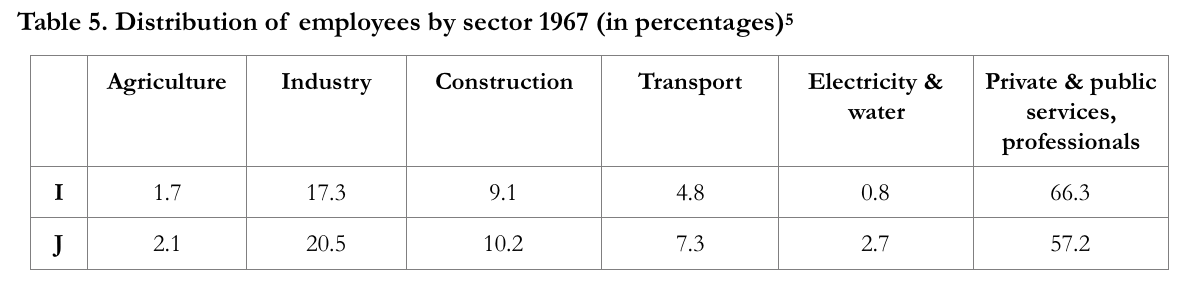

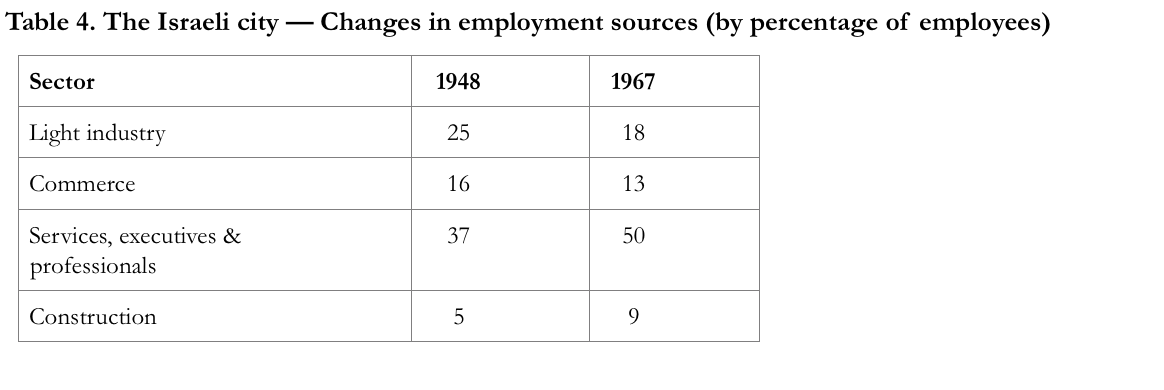

In both cities, most employees worked in services, either in the private or public sector (see Tables 4 and 5). The tourism industry was the dominant source of income in the Jordanian city, employing over 50 per cent of the workers across the different professions in the industry. In 1966, Qalandia airport became an international terminal serving about 100,000 passengers travelling to international destinations nearby. In the same year, about 600,000 tourists visited Jordanian Jerusalem, of whom 175,000 came from western countries.

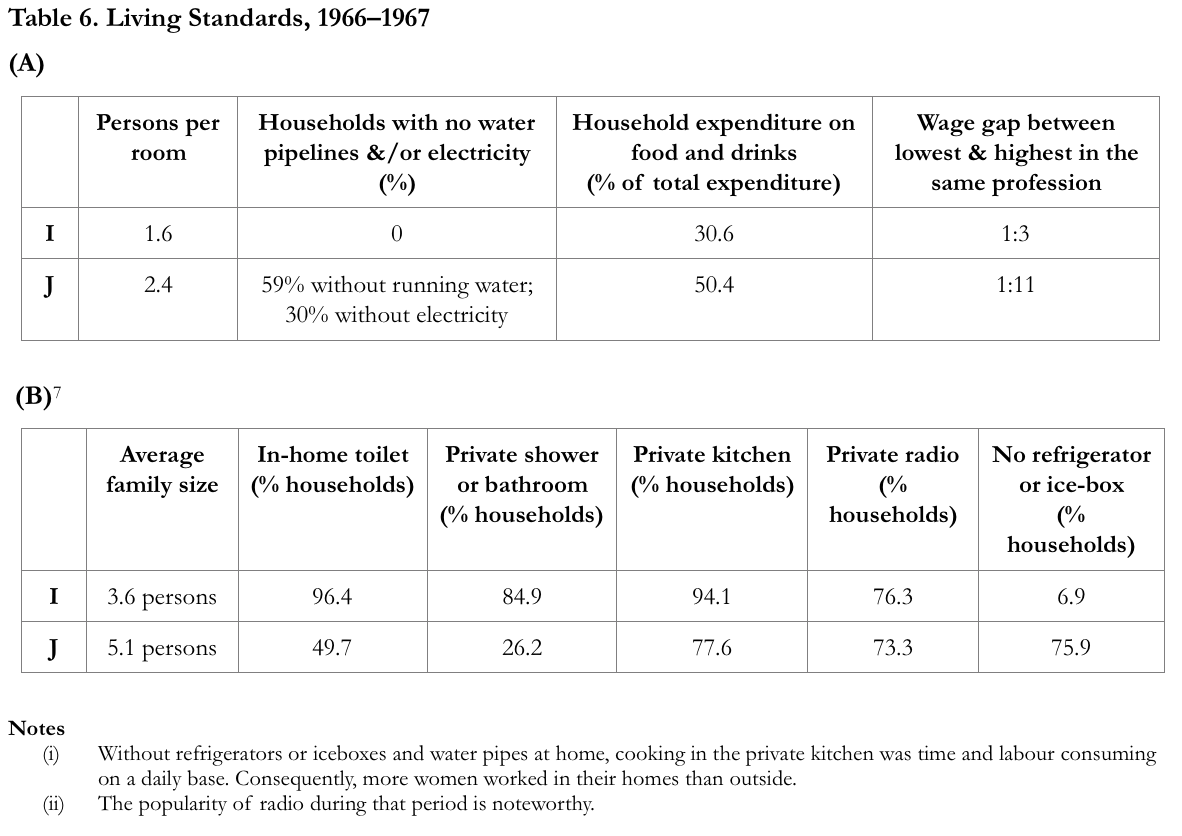

Pre-occupation income gap data show that wide gaps existed between the two cities where unskilled jobs or jobs requiring low skills were concerned, eg construction work or low-level office work. The income gaps between the two cities narrowed, however, where skilled, professional or management jobs were concerned (see Table 6A).About 10 per cent of the residents of each city worked in construction (see Table 5). It should be noted that in any two-year period before 1967, Israel built on its side of Jerusalem more houses than Jordan did throughout the entire 19 years of its rule in Jordanian Jerusalem. Furthermore, in the mid-1960s, women constituted just 9 per cent of the labour market in Jordanian Jerusalem, but 33 per cent in the Israeli city.

In terms of living costs, owing to Israeli import duties and the cost of labour, Israeli Jerusalemites paid 40–50 per cent more than their Jordanian counterparts did for the same basket of goods. A kilogram of meat, for instance, cost 9.20 IL in the Israeli city but just 3.50 IL in the Jordanian city. Living conditions in the Israeli city were generally better than those in the Jordanian city. (See Table 6B.)

Nine bank branches and three cinemas served residents and tourists in the Jordanian city. The Israel city, in contrast, had 14 cinemas and 58 banks [6]. The Jordanian city had no university while on the Israeli side, the Hebrew University attracted many students from all over Israel and prepared the next generation of professionals and scientists.

An official Israeli survey of 994 shops outside the Old City in July 1968 found that 926 of them were sole proprietorships, meaning, no branches of big chains existed then [8]. The owners were mostly middle class members, as shown by place of residence [9]. The survey found also that there were 64 hotels and guest houses in East Jerusalem, 51 outside the Old City walls and 13 within it. In addition, there were 99 coffee shops and food stalls in the Old City [10].

Conclusion

Fearing the rise in Jerusalem of Palestinian national aspirations, which had already sprung up during the Mandate period, the Hashemite regime consistently worked to strengthen Amman’s political and economic status while keeping Jerusalem underdeveloped. Subsequently, when the anti-Hashemite opposition created unrest in the West Bank in 1955-1957, Jerusalem became the focal point for a stormy demonstration. The Jordanian government responded by crushing the demonstration and imposing martial law in the city.

Although Israeli Jerusalem was a capital, it enjoyed the tranquillity of a provincial city at the end of a narrow road towards the coastal plain because Israel’s main security, political, economic, commercial and press centres were located in Tel Aviv. Just like its Jordanian counterpart, which styled East Jerusalem its spiritual capital, Israel, before the 1967 war, attached higher symbolic status to its side of Jerusalem than the city actually had. But, where Jordan continued to present Jerusalem just as a holy city, Israel built its side of Jerusalem into a national centre, with reinvented traditions based on Mt. Zion’s Jewish holiness being only secondary.

About the Author

Professor Menachem Klein is a faculty member of the Department of Political Science at Bar-Ilan University, Israel. He was a fellow of St Antony’s College, Oxford University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the European University, Leiden University and King’s College London. In 2000, Professor Klein was an adviser for Jerusalem affairs and Israel–PLO final status talks to then Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak. His most recent publication is Arafat and Abbas: Portraits of Leadership in a State Postponed (London: Hurst; New York: Oxford University Press, 2019). His book Lives in Common: Arabs and Jews in Jerusalem, Jaffa and Hebron (New York: Oxford University Press; London: Hurst, 2014), which was also published in German and Hebrew, was named one of the best non-fiction books of 2014 by The New Republic magazine.

Image caption: A picture taken on 11 February 2020 shows the Israeli settlement of Pisgat Zeev (on the left), built in a suburb of the mostly Arab east Jerusalem, and the Palestinian Shuafat refugee camp (on the right) behind Israel’s controversial separation wall. (Photo by Ahmad Gharabli / AFP)

Footnotes

[1] This paper is part of a work in progress on urban realities and everyday life in divided Jerusalem. Unless mentioned otherwise, I relied on two of Meron Benvenisti’s books containing the same data, albeit in different languages, namely, Jerusalem: the Torn City [in Hebrew] (Jerusalem/Weidenfeild and Nicolson, 1973), 82–116; and [in English] (Jerusalem/Isratypset, 1976), 17–62. As East Jerusalem administrator from 1967 to 1978, Benvenisti was able to obtain Jordanian documents that Israel took possession of following its occupation of the city in 1967. These include minutes of city council meetings, as well as mayors’ and governors’ papers, and surveys that Israeli agencies undertook in East Jerusalem between 1967 and 1968. Benvenisti deposited his archives, including these documents, in Yad Ben Zvi library, Jerusalem. I have complemented his data with information from other Israeli primary sources.

[2] Uzi Benziman, Jerusalem: A City Without A Wall [in Hebrew] (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv: Schocken, 1973), 177.

[3] Lives in Common: Arabs and Jews in Jerusalem, Jaffa and Hebron (London: Hurst: New York: Oxford University Press), 2014

[4] These included neighbourhoods such as Talpiot, Katamonim, Kiryat Yovel, Mussrarah and Sanhedriyah.

[5] Benziman, Jerusalem: A City Without A Wall.

[6] Bank of Israel, Statistics of Financial Institutions, January 1969, https://www.boi.org.il/he/BankingSupervision/Data/Documents/historicalinfo/1969/%D7%A1%D7%98%D7%98%D7%99%D7%A1%D7%98%D7%99%D7%A7%D7%94%20%D7%A9%D7%9C%20%D7%94%D7%9E%D7%95%D7%A1%D7%93%D7%95%D7%AA%20%D7%94%D7%91%D7%A0%D7%A7%D7%90%D7%99%D7%99%D7%9D_0169_00030001.pdf.

[7] Benziman, Jerusalem: A City Without A Wall.

[8] Of the 994 shops, 355 were in the food business (cafes, restaurants, bakeries, groceries, butcheries) and 82 were souvenir shops. The rest included shoemakers (41), tailors (33), moneychangers (2) and electrical goods shops (2).

[9] About half of the owners (471) lived in the Old City, whereas 456 lived outside it, mostly in Wadi Joz (112), Beit Hanina (63), Shouafat (61) Silwan (46) and Abu Tor (46).

[10] Israel State Archive, Israeli Land Authority East Jerusalem Branch, גל 13926/14 [in Hebrew], http://www.archives.gov.il/archives/#/Archive/0b0717068002f157/File/0b071706808702a0. The survey was made in order to find land and properties available for Israel to take over, including pre-1948 Jewish properties and land or properties owned by absentees or citizens of enemy countries.