This essay seeks to document the fate of the Palestinians who remained in the Israeli-occupied part of Jerusalem after the city was partitioned in 1948 between the newly created state of Israel and the kingdom of Jordan. Drawing largely from the unpublished diary of a Palestinian Jerusalamite, it represents an attempt to rethink history from the margins, rather than present the mainstream perspective based on government documents and political statements. Although the conditions described occurred more than seven decades ago, some of them persist in the city to this day.

CLICK HERE FOR THE PDF.

By Issam Nassar

In November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly passed resolution 181 for the partition of historical Palestine. According to the plan, Jerusalem was to become a separate entity, a corpus separatum, to be governed by a special international regime. But neither the partition plan nor the corpus separatum plan was implemented. Instead, fierce battles ensued between the Zionist militias and Palestinian fighters over control of Jerusalem. Within five months, Jerusalem was effectively partitioned between Jordan and the newly created state of Israel. And so began the plight of the Palestinians: they would soon cease to be citizens and would lose their Palestinian identity, being termed “Arab refugees” instead.

Diaries and other personal papers are not usually the main sources that traditional historians use in their work, but they have the power to illustrate how historical events transformed the lives of ordinary people. This essay deals with the fate of the Palestinians who were expelled from, or fled, their homes in the Israeli-occupied part of Jerusalem in 1948 and especially the fate of the few who managed to remain behind. Its primary source is the unpublished diary of one such Palestinian who wrote about his painful quotidian existence.

The voices of the Palestinian victims scattered in refugee camps in the surrounding countries were eventually heard, especially after the rise of the Palestinian resistance movement in the aftermath of the 1967 war, in which Israel occupied the rest of Palestine. But the voices of those who remained inside their homeland were largely erased from historical memory. This study, therefore, focuses on the transitional phase between 1948 and 1967, particularly on the first two uncertain years following de facto partition. Understanding the fate of Jerusalem, and the entire Palestinian conflict, will not be complete without serious consideration of what happened in the city at the time.

Background

By the end of April 1948, Zionist forces had occupied the western suburbs of Jerusalem, or the New City, as the area was called. This was where many important Arab neighbourhoods were located, including al-Baq’a and al-Qatamon. The Arab residents in the area numbered about 30,000, according to most reliable sources, although one source places the number at 60,000.[1] Many of these Arabs were pushed out and prevented from returning by the advancing Zionist forces and, later, by the state of Israel; some fled in fear of their lives following the gruesome Zionist massacre of Palestinians in the neighbouring village of Deir Yassin on 9 April 1948.

The eastern part of the city remained in Arab hands and was taken over by Jordan shortly afterwards. That part included the Old City and the villages to the north and the east. The majority of the Jews living in the Old City were exchanged in a “prisoner” swap between Jordan and Israel, but the Jews living in the surrounding settlements fled into what became Israel. The exchange involved largely civilians although some of those swapped were fighters from the Haganah Zionist militia.

Initially, the transitional Israeli government considered the western part of Jerusalem that had fallen under its control to be “territory occupied by Israel”.[2] However, following the signing of the armistice between Israel and Jordan on 3 April 1949, which determined the border between the two states on the basis of the realities on the ground,[3] the Israeli government declared that West Jerusalem was no longer considered occupied territory but part of the state of Israel.

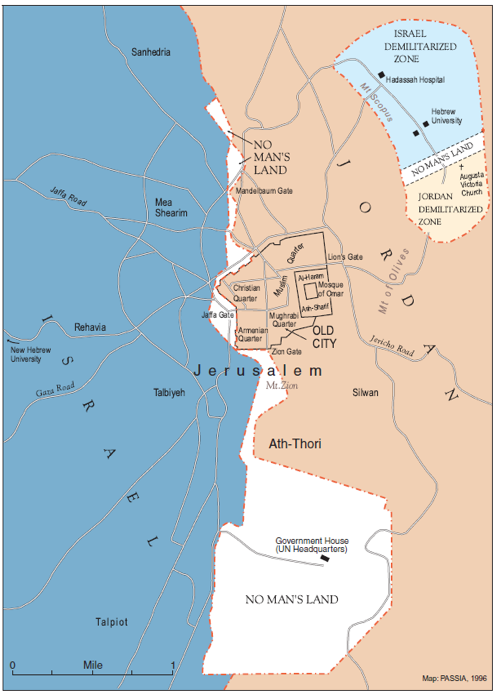

Barbed wire and a demilitarised no-man’s land now separated the Israeli and Jordanian sectors of Jerusalem (see figure 1). Mandelbaum Gate was the only crossing point between Israel and Jordan at the time. A UN peacekeeping camp was located between the two sectors of the city.[4] UN peacekeepers and international diplomats were allowed to cross the gate freely and Christians from the Galilee were permitted to cross over to participate in Christmas celebrations in the Old City. However, for Palestinian Jerusalemites under Israel’s control, crossing this checkpoint into Jordanian-controlled areas was usually a one-way journey, with no possibility of return.

Figure 1. Partitioned Jerusalem, 1948–1967

Source: Passia.org, http://passia.org/media/filer_public/df/f5/dff5b344-258f-441e-97b5-33194bde7356/pdfresizercom-pdf-crop_53.pdf

Refugees in their Own Homeland

This essay is based on the diary of a Palestinian Jerusalamite, Jeries Salti, who remained in the West Jerusalem suburb of al-Baq’a. Salti and his family were among the only few hundred or so who remained in the western suburbs following the Zionist capture and the expulsion or flight of Arabs.[5] Salti’s diary is unique in a number of ways in the Palestinian discourse on the nakba, or Palestinian catastrophe, of 1948. Notably, it illustrates that the catastrophe touched not only poor villagers but also wealthier residents: a large number of residents in the western suburbs were middle class Palestinians. Before the unfolding events, Salti himself had been a successful businessman who owned a construction metal store in the city in partnership with his nephew.[6]

The essay also draws on published diaries, including that of John Rose, whose father, a British national, had arrived in Jerusalem with General Edmund Allenby, whose forces conquered Jerusalem in late 1917, and that of Hala Sakakini, the daughter of the renowned educator Khalil Sakakini. While Sakakini and her family fled just before the fall of West Jerusalem, Salti and Rose chose to remain. Their decision to remain could not have been an easy one, judging from the ferocity of the final Zionist attack on the neighbouring suburb of Qatamon, as described by Sakakini. In a diary entry on 29 April 1948, the day she and her family fled Qatamon for Egypt, Sakakini described the attack thus:

At twelve o’clock (the usual hour), not long after our visitors [Abu Dayyeh and Abu ‘Ata] had left us, the attack on Katamon began. It was stronger than ever. The firing was heavy and continuous and it sounded so very near all of us thought that the Jews had reached our street. Every one of us deep down in his heart feared that before morning we would all be dead.[7]

Sitting in a temporary home in al-Baq’a, a little over a year after the fall of the area, Salti wrote in an unused old diary what would become the first line in his year-long journal, “We started writing in this diary on Friday, 13 May 1949.” It had been a whole year since Salti and his family members had seen any of their loved ones who had departed for, or were living in, what had become the Jordanian side of the city. Staying on with him were his wife, Mudallaleh; his three daughters, Adele, Hind and Nada; one of his sons, Raja; his sister, Nazha Sahar, and her son, Abdullah; and a second, unnamed sister.

Restrictions on Movement and Confiscation of Property

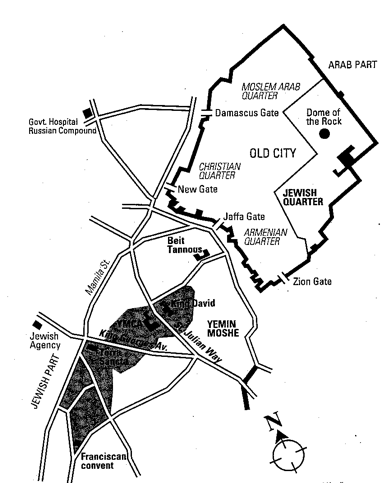

In September 1948, the Israeli authorities erected barbed wire around a small area — about 1.3 km in size — within al-Baq’a. [8] This was intended to form a security zone and enforce greater control over the Palestinians in and around the area. As Rose noted: “[t]he creation of the zone was not good news for the few who lived outside it. They were told that for their own protection they had to move into an abandoned house of their choice within the fenced area.”[9] The Saltis, like Rose, were among those whose houses were outside of the zone, so they were forced to move into someone else’s house inside the zone. Within the enclosed “Zone A”, as it was called, residents were allowed to move freely during the day but were subjected to a curfew at night (see Figure 2 for location of the zone).

Figure 2. A rough representation of where “Zone A” was located.

Courtesy of Salman Abu Sitta

The Israeli authorities then began giving the houses outside the zone that belonged to Arabs like the Saltis and the Roses to Jews who needed homes, thus creating a new reality on the ground. But as the houses outside the zone became occupied, Jews soon began entering Zone A and taking over empty homes there as well. Some zealots among the Jews from outside would drive noisy motorcycles in al-Baq’a late at night, making a commotion in the hope of scaring the Arab residents into abandoning their homes. In fact, as Salti’s journal entry of 19 October 1949 illustrates, some Jews were doing more than taking over empty Arab houses: “the situation is getting worse. The Jews are squatting even in inhabited Arab houses aiming to take over a room.”

It was only in November 1949, when the Arab residents of West Jerusalem were granted temporary identity cards by the Israeli state and those Palestinians who had been forced into Zone A were allowed freedom of movement again, that many realised their properties had been confiscated by the government. Although the city had not been officially annexed by Israel at that time, the Israeli government had already “employed its Absentee Property Regulations to confiscate all Arab homes, lands and businesses, including any contents that had not been already looted”.[10] Those regulations were eventually codified under Knesset Law Number 20 of 1950, which created the office of the Custodian of Absentee Property for the properties of Palestinian refugees, including real estate, currency, financial instruments and other goods, and allowed the rental and sale of such properties.[11] Ironically, although the Palestinians who remained in the Israeli section of Jerusalem were not “absentees” as defined by the law, they lost their properties and were treated like squatters and foreigners.[12] An entry in Salti’s journal dated 22 June 1949 describes how the authorities treated the Palestinians:

Today a Jewish [meaning an Israeli] official went around the Arab houses and recorded the names of those residing there so they can start collecting rent from them.

Theft was not limited to squatting in Arab homes but extended to raiding homes to take furniture, home appliances, jewellery, and even doors, windows and bathroom tiles. Rose wrote the following account about a looting incident that he had witnessed:

Next day at about four in the afternoon a truck stopped outside the front gates. Five armed men made their way to the top floor. We remained indoors and watched as they threw mattresses, cushions, bedding and other unbreakable items through the windows down to the garden below. Furniture they carried by the staircase. The last man to leave took the oude which he had found on top of the cupboard. The looters threw the keys back at us contemptuously and showed no regret for their actions. As soon as they were out of sight we went upstairs to tidy up what was left in the ransacked flat, much shaken by this threatening experience and dreading what would happen next.[13]

Figure 3. New Jewish immigrants moving a couch from an abandoned home in Ein Karem

Source: Israeli Government Press Office (GPO), Jerusalem.

And, individual Jews were not the only ones involved in the looting. Police often conducted searches of Arab homes under the guise of security, and looting during such searches was not uncommon.

The Saltis spent their first year after the conquest largely confined to their home, venturing out only when absolutely necessary, such as to seek food or to see the lawyer who represented them in a case against the Israeli authorities. Although al-Baq’a still had a number of families, it looked like a deserted town as most of these families, like the Saltis, avoided being seen outside. The only passers-by were cats, wild dogs, Israelis in armoured vehicles, and irregular Jewish forces, who would capture and expel any Arab they came across to the Jordanian side of the city.

Clandestine Cross-border Contacts

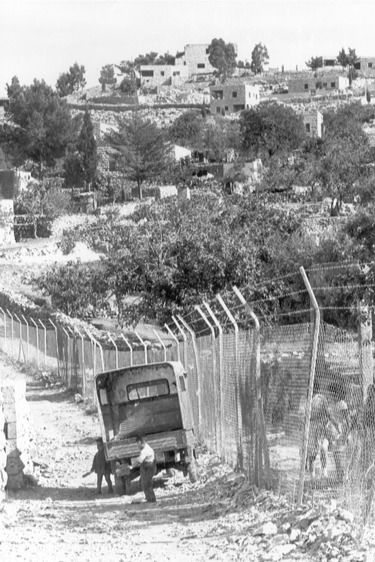

The number of officially sanctioned visits from the Israeli side to the Jordanian side and vice versa was limited and the contacts heavily restricted. Owing to the extreme circumstances in occupied Jerusalem, some Palestinians maintained illegal contacts with Palestinians on the other side of the barbed wire. These clandestine meetings took place in the early hours of the morning at the fence that split the village of Beit Safafa into Israeli and Jordanian sections. (See Figure 4.) Through these legal and illegal contacts, food, personal items and other goods were exchanged. Several entries in Salti’s journal describe the encounters across the fence that his family had with relatives from the other side. Since his food stock had run out and he was prevented from shopping by virtue of his location and his lack of money, Salti was overjoyed upon seeing items brought to his family from the Jordanian side. In a diary entry from 24 May 1949, he wrote:

Sitt (madam) Nuha Halaby arrived from the Old City — on the Jordanian side of the city — and brought with her some stuff sent by Sami and Jeryis al-Luci and the children of Abu Roufa. We were very happy with what we got, particularly with the cucumbers, tomatoes and meat. Hind and Adele were happy with their new shoes and Raja with the sandals and so was Um Sami with her new shoes as well. I was glad to see rice, sugar sent to us by George al-Luci … and the two bottles of arak and peanuts that he sent.

Salti’s diary shows that these encounters at the fence with relatives had become highly meaningful for the Palestinians and often constituted the highlights of their lives even if they carried the risk of being spotted by police. In fact, in an entry in August 1949, we learn that Beit Safafa had become the community’s window to the world: people would go to the fence at great risk just to talk to anybody who happened to be on the other side.

On 29 May 1949, Salti made what appears to be his first clandestine visit to Beit Safafa and met another one of his sons and an in-law:

Today at 6 am we all went to Beit Safafa, including Nada and Raja [the youngest of the children]. There we saw Sami [Salti’s older son] and my in-law George al-Luci. We were very happy to see them and we prayed to God that nothing should happen that would ruin our reunion such as being seen by one of the Jews.

Figure 4. The fence dividing Beit Safafa, seen from the Israeli side, 1 November 1949

Source: Cohen Fritz, GPO

Being caught by the police was not the only risk Palestinians on the Israeli side were taking when they went to the “border areas”. Salti’s journal entry on 9 September 1949 describes a tragic event that occurred when a family was returning from Beit Safafa:

Today we heard the most terrible news. Yousef Abu Khalil and his five daughters were on their way to their original home — which was reduced to a pile of rubble — on the road between Beit Safafa and Bethlehem to pick fruits from their trees. After they picked grapes and figs and were on their way back, a mine exploded under their feet. His most beautiful daughter of 23 was killed instantly, her two sisters are now hospitalised in critical condition and Yousef himself was wounded.

A few days later, Salti wrote that one of the two wounded girls had died in hospital.

Salti’s Cause

The store owned by the Saltis, Salti Iron Store, was located in al-Shama’a. Although this was within the uninhabited and largely destroyed no-man’s land that was supposedly under neither side’s control, the Saltis were unable to reach their store to retrieve any of their property. Then, one day early in 1949, Salti, whose existence within the boundaries of the state had been bordering on the clandestine, suddenly found that he had a cause worth fighting for: he learnt from a Jewish acquaintance that the Israeli army had pillaged the entire contents of his store.[14] The pillaged items were estimated to be worth £100,000. Enraged, Salti then decided to go to court to seek redress against the Custodian of Absentee Property since he was legally not an “absentee”.

Salti meticulously recorded in his journal everything related to the court case, from the court sessions, his efforts to collect evidence connected to the case, his frequent visits to his Jewish lawyer and the latter’s requests to bring him gifts, including whiskey smuggled in from East Jerusalem. In fact, it is plausible that Salti began his diary so that he could keep a record of all the events surrounding the case, and in the process ended up documenting much more. Had it not been for the extraordinary conditions under which Salti was living, his journal would have been considered mundane.

Conspicuously absent in Salti’s chronicles is any reference to the national question or the larger political situation. It is possible that the hardships of daily life, such as scarcity of money and food, left Salti little time to contemplate on issues of such nature. It is also possible that he was being careful not to have a written record that could fall into the wrong hands and jeopardise his right to continue residing in his hometown.

Although Salti won his case, he failed to get the compensation owed to him by the state. The ensuing negotiations with the authorities resulted in Salti eventually agreeing to accept only £10,000 instead of the £100,000 that the court had ruled he was entitled to.

Salti’s legal troubles with the authorities were not over, though. Upon his return from Zone A, he threatened to go back to court, this time to evict those who had taken over his house. Eventually, in October 1949, Salti and his family got back their home but not through a fair implementation of the law. As his diary reveals, winning back his home involved intense negotiations with the occupants.

Life in a Liminal Space

Despite these small victories, Salti’s life remained far from normal. His journal entries continued to reflect a sense of sadness and desperation, often in the form of oblique references and prayers at the end of each entry. Using terms such as “my patience is running out” and “the situation is rather depressing”, Salti was in effect reflecting on the state of liminality in which he and the remaining members of the Palestinian community found themselves.

Victor Turner describes liminal space as the “interstructural situation” or the condition of betwixt and between.[15] The concept refers to a transitional phase or situation where a person finds herself between two different worlds but not within either of them. By being in Israel but not of it, the Arabs of West Jerusalem existed in a transitional space; they were neither fully in the state of Israel, nor did they have ties with the rest of their community outside of it. Their streets, houses and gardens stood right in front of their eyes, but these no longer belonged to them. Instead, these Arabs were surrounded by strangers — strangers who were oblivious of the presence of the Arabs but who saw the latters’ houses and belongings as booty they could easily claim. In this sense, despite remaining in their own neighbourhoods, the Palestinians of West Jerusalem shared the experience of displacement with Palestinians in refugee camps overseas. Their obliteration from the everyday life around them, together with the opening up of their neighbourhoods and property for Jewish settlers to appropriate, was symptomatic of the way Zionism saw the land of Palestine while negating its people.

It is precisely in this context that Salti’s journal is most significant. For it gives voice and an agency to the Palestinians silenced in the dominant historical narrative of Israel’s founding. And, it does so without the slightest nationalist undertone. Salti’s account adds to a more humanised and profound understanding of the Palestinian experience. It offers an exceptional opportunity to see Israel not as it imagined itself to be then — a project of salvation and redemption — but as what it was to the natives: a colonial project. Reading the journal clearly brings to mind what Walter Benjamin philosophically once described as “the state of emergency”, which is not the exception but the rule, adding that “we must attain a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight” in order to improve our position in the struggle against fascism.[16] For the Palestinians, the state of exception that began in 1948 seems to have become the rule. Not only have they not returned to their homes or homeland in accordance with UN resolution 194, which stipulated their right to do so, but they have also continued to live in conditions of oppression ever since.[17]

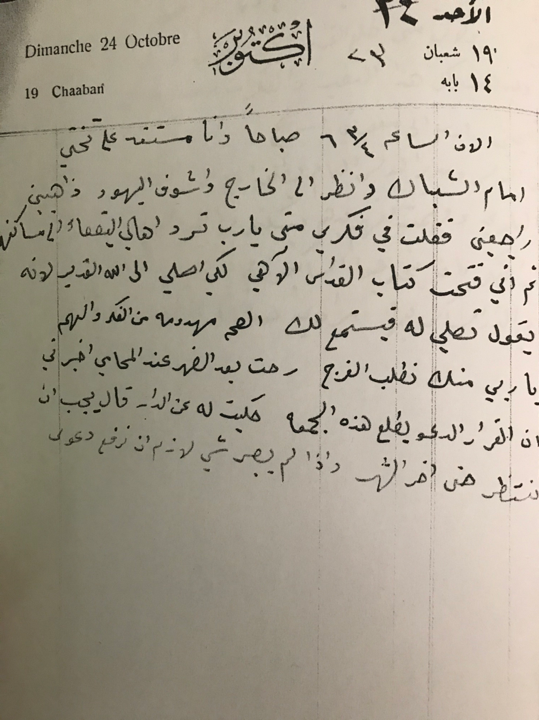

Figure 5. One of Salti’s Last Few Journal Entries

Source: Courtesy of Raja Salti

In an entry in his journal dated 23 October 1949, Salti wrote: “It is now 6.45 am, and, as I lie on my bed next to the window, I can see the Jews outside coming and going; I say to myself when will the people of al-Baq’a return to their homes?” Salti’s longing still applies today to many Palestinians, who wonder when their permanent state of emergency will end.

About the Author

Dr Issam Nassar is a professor of Modern Middle East History at Illinois State University and a professor of History at the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies in Qatar. He was the co-editor of Jerusalem Quarterly and author of a number of books and essays on the history of Jerusalem, Palestine, and photography in the Ottoman world. Among his latest publications is The History of the Palestinians and their National Movement (Institute of Palestine Studies, 2018), co-authored with Maher Charif, and The Storyteller of Jerusalem: The Lives and Times of Musician Wasif Jawharriyeh (Institute of Palestine Studies, 2013), co-edited with Salim Tamari.

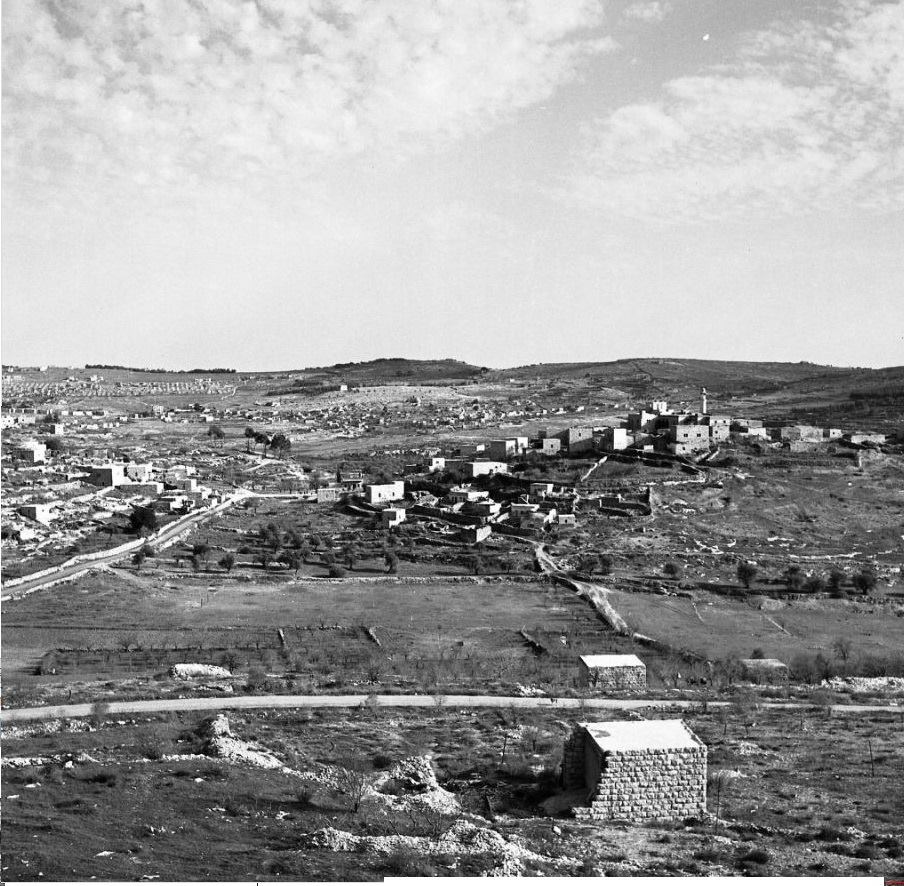

Image caption: View of Palestinian Arab villages al-Maliha and Beit Safafa. Photo: Central Zionist Archives, shared on Wikimedia Commons.

Footnotes

[1] According to Nathan Krystall, before the nakba (Palestinian catastrophe), 28,000 Arabs lived in the western suburbs of Jerusalem — excluding the neighbouring villages. See Nathan Krystall, “The Fall of the New City: 1947–1950”, in Salim Tamari, ed, Jerusalem 1948: The Arab Neighborhoods and their Fate in the War, 2nd edition (Jerusalem: Institute of Jerusalem Studies and Badil, 2002), 85. However, Ibrahim Matar places the number of exiles and refugees from West Jerusalem at 60,000. See Ibrahim Matar, “The Jewish Conquest of West and East Jerusalem: 1948 to the Present”, Palestine–Israel Journal of Politics, Economics & Culture, March, 2011, 214.

[2] Krystall, “The Fall of the New City 1947–1950”, 112.

[3] The text of the armistice can be found on the UN website on the Question of Palestine, https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-189953/.

[4] Bernard Wasserstein, Divided Jerusalem: The Struggle for the Holy City (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002), 180.

[5] The exact number of residents who remained is hard to determine. According to one resident of the area at that time — Raja Salti, son of Jeries Salti — the number did not exceed 200. (Interview with Raja Salti, Ramallah, 7 August 2007.) But, according to David Ben Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, the number was around 1,000. See David Ben-Gurion, Israel: A Personal History (New York: Funk and Wagnalls, Inc, 1971), 183. The discrepancy might be due to whether or not those who remained in the nearby villages were included in the count.

[6] The diary is being edited for publication and will be published in Arabic in 2020 by the Institute for Palestine Studies in Beirut.

[7] Hala Sakakini, Jerusalem and I (Jerusalem: Commercial Press, 1987), 121

[8] John H. Melkon Rose, Armenians of Jerusalem: Memories of Life in Palestine (London and New York: The Radcliffe Press, 1993), 205.

[9] Rose, Armenians of Jerusalem, 206.

[10] Krystall, “The Fall of the City”, 113.

[11] The text of the law is carried on the website of the Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, https://www.adalah.org/en/law/view/538.

[12] An absentee, according to the Knesset law number 20, was a person who, after 29 November 1947, had visited an Arab country or was a national of such a country, or who normally resided in Palestine but left his ordinary place of residence for a place outside of Palestine before 1 September 1948. See footnote 12.

[13] Rose, Armenians of Jerusalem, 215.

[14] Interview with Raja Salti, Ramallah 7 August 2007.

[15] See Dag Oistein Endsjo, “To Lock up Eleusis: A Question of Liminal Space”, Numen 47, no. 4 (2000), 351–386.

[16] Walter Benjamin’s VIII Thesis on History in Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, translated by Harry Zohn (New York: Schockten Books, reprint of 1969 edition), 266.

[17] For the complete text of UN resolution 194 see the website of the UN Question on Palestine, https://unispal.un.org/DPA/DPR/unispal.nsf/0/C758572B78D1CD0085256BCF0077E51A.