Jerusalem is unique among the issues underlying the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: it is not just a bilateral issue between Palestinians and Israelis; Jerusalem also houses sites considered holy by the world’s three major faiths: Islam, Christianity and Judaism. Thus, the fate of Jerusalem can have lessons or even repercussions for multi-confessional countries outside the Middle East where religion is a source of political contestation or is one of several factors driving militancy. Religious conflicts within a state may be contained if the rule of law implemented by the sovereign power is recognised as broadly legitimate. In the conflicts over the holy sites in Jerusalem, however, the Israeli state’s authority is constantly undermined by its lack of legitimacy in East Jerusalem, given its partiality towards Israeli Jews as well as the fluidity if the city’s borders as it rapidly expanded in the 20th century.

CLICK HERE FOR THE PDF.

By Michael Dumper

Why should Jerusalem be of interest to Singapore? We should note that Singapore lies in a politically dynamic and multi-confessional region with significant overlapping of beliefs and values. In many cases, these beliefs and values are expressed in political and sometimes militant terms. Just to the southwest of Singapore lies Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim country, where religion is increasingly becoming politicised; to the east, the militant Abu Sayyaf group is active in the Philippines; to the north, there is evidence of a revival of Salafi-inspired activism in Malaysia while Buddhist-Muslim tensions are rife in Myanmar; finally, to the west, an increasingly Arabised South Indian Muslim community is emerging in Kerala while a violent outbreak of Muslim-Christian tensions was witnessed recently in Sri Lanka.

The region, in short, is a volatile mix of religions, ethnicities and national identities often waiting to erupt into political violence. The religious dimension of these tensions brings the role of Jerusalem as a holy city to the fore, and tensions in the Middle East and in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict contribute to this volatility. Therefore, there is clearly a need for academics and policymakers in Singapore to keep an eye on the region and on developments in Jerusalem.

***

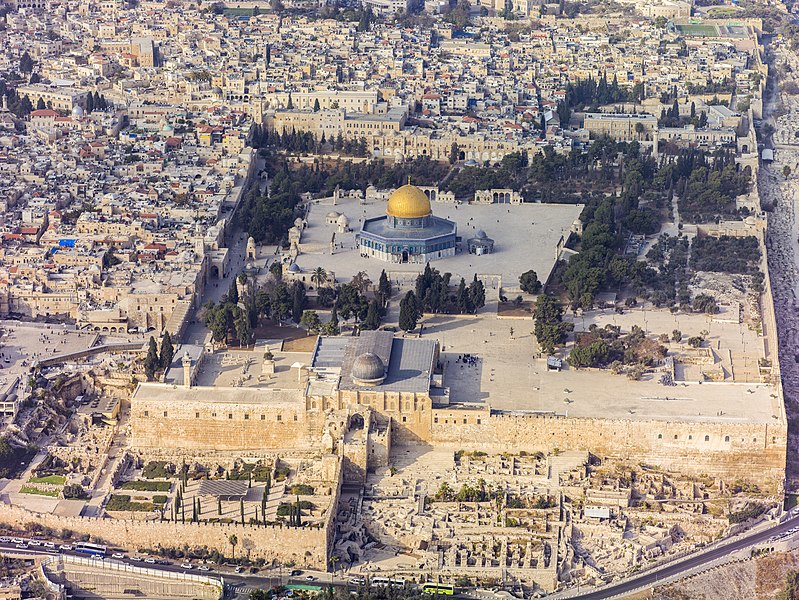

Jerusalem is crammed full of religious sites and associated buildings, which has played a key part in framing the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. The most important religious sites of Judaism, Christianity and Islam are sometimes found on top of each other, in what is a relatively small city.[1] For Judaism, the Temple Mount (Har Habayit) is the primary site and comprises the ruins of what are known as the First and Second Temples. The Wailing (or Western) Wall is now the only visible reminder of its destruction in AD70. Located on the Temple Mount is also the “Holy of Holies” of the Israelite tribes, presided over by the priestly elite. For Muslims, standing in the exact same location is the Haram al-Sharif (or Noble Sanctuary), one of the three holiest sites in Islam, the other two being Mecca and Medina. It contains the Dome of the Rock, where the Prophet Muhammed is believed to have ascended briefly to heaven, and Al-Aqsa mosque, towards which the first Muslims prayed before the decision to face Mecca was made. In Islam, the Wailing Wall is known as al-buraq in Arabic and it is believed to be the site where the prophet tethered his horse during his ascension to heaven. Located nearby is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the pre-eminent Christian holy site, which marks Golgotha, where Jesus Christ is believed to have been crucified after his final walk along the Via Dolorosa, which runs through most of the Old City.

Thus, Jerusalem is holy not just to one monotheistic religion of the world, but three. These three religions have emerged from one another’s traditions and cultures and have elements of doctrine and ritual that both overlap and are embedded in one another. In this way, layer upon layer of faith and belief have been deposited upon the city. Having lived in and visited the city many times since 1977, I have become so accustomed to the plurality of faiths and the variety of rituals on the streets that it has become easy to overlook this uniqueness.[2]

Before examining how these religious traditions play their part in the political dynamics of the city, taking a snapshot of the current situation will give us a strong idea why understanding Jerusalem continues to be critical in understanding the conflicts of the Middle East region.

***

In December 2017, the US government declared that it would recognise Jerusalem as the capital of the state of Israel and that its embassy would be re-located from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. This was a momentous decision whose consequences are still being played out today. Until this announcement, the US embassy, together with every other embassy in Israel, had been located in Tel Aviv and not in Jerusalem.[3] This comprehensive diplomatic boycott by the international community was a sign that it did not recognise the city as the capital of Israel and that its future governance was still subject to negotiations.

The dramatic change in US policy had two effects. The first was the damage done to the prospect of peace negotiations over the city in the near future. By recognising Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and moving its embassy to the city, in one stroke, the United States had taken the issue of Jerusalem off the negotiating table. Because of the central role played by the United States in the Palestinian-Israeli peace negotiations, the US decision had pre-empted the possibility of Palestinian counterclaims to the city being considered and consequently nullified the purpose of these negotiations. The second impact was to remove the United States as a potential broker for any agreement between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). As important, however, is the fact that the US decision also postponed negotiations over other important issues: the evacuation of Israeli colonies or settlements from the occupied Palestinian territories, security co-operation, and Israeli recognition of the state of Palestine. Without progress on the Jerusalem issue, there could be no agreement on these other important issues.

To many experts and observers of the Jerusalem issue, the US decision was confusing and related directly to the lack of clarity over the geographical area termed “Jerusalem”. The announcement specified that the United States was taking “no position on boundaries or borders”.[4] But what did this mean? That the United States recognised Israeli sovereignty over both Israeli West Jerusalem and Palestinian East Jerusalem? If so, then which borders in East Jerusalem was it recognising as part of the capital of Israel? Scholars of Jerusalem will point out that there are quite a few boundaries, walls, barriers and borders, and not all of them are congruent with each other. So what was the United States actually recognising? Which parts of Jerusalem were to be regarded as Israeli?

Fluid Borders

Why is this lack of clarity important and how did it arise in the first place? A critical element running through the various stages in the modern history of Jerusalem is the fluidity of the borders of the city as it rapidly expanded in the 20th century and as it was contested by Palestinian and Israeli nationalism. My overall contention is that Jerusalem is a city of many borders — which has simultaneously led to many challenges for policymakers but also offered up some opportunities for negotiation between the opposing parties.

In 1922, following the defeat of Turkish forces in the First World War, the British Mandate for Palestine was recognised by the international community. A key British policy that was fundamentally at odds with the Palestinian goal of independence was the policy to advance a Jewish national home in Palestine, which had been initiated under the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and incorporated into the terms of the mandate. Jerusalem, with its many iconic religious sites, as well as its role as the centre of colonial government, thus became one of the arenas where Palestinian and Jewish, later Israeli, nationalism fought.

The rapid expansion of Jerusalem outside the walls of the city, and hence its boundaries and borders, began with the establishment of the British Mandate. New employment opportunities in government and municipal services drew in Palestinians from the hinterland. In addition, the increased inflow of Jewish settlers as a result of the Jewish National Home Policy led to overcrowding and congestion in the city. New neighbourhoods were created, mostly in the west of the city, and roads to the surrounding villages were improved, bringing them even further into the city’s orbit. As a result, the British introduced a series of extensions to the city’s municipal borders.

Fast Forward to 1948: the Partitioning of Jerusalem

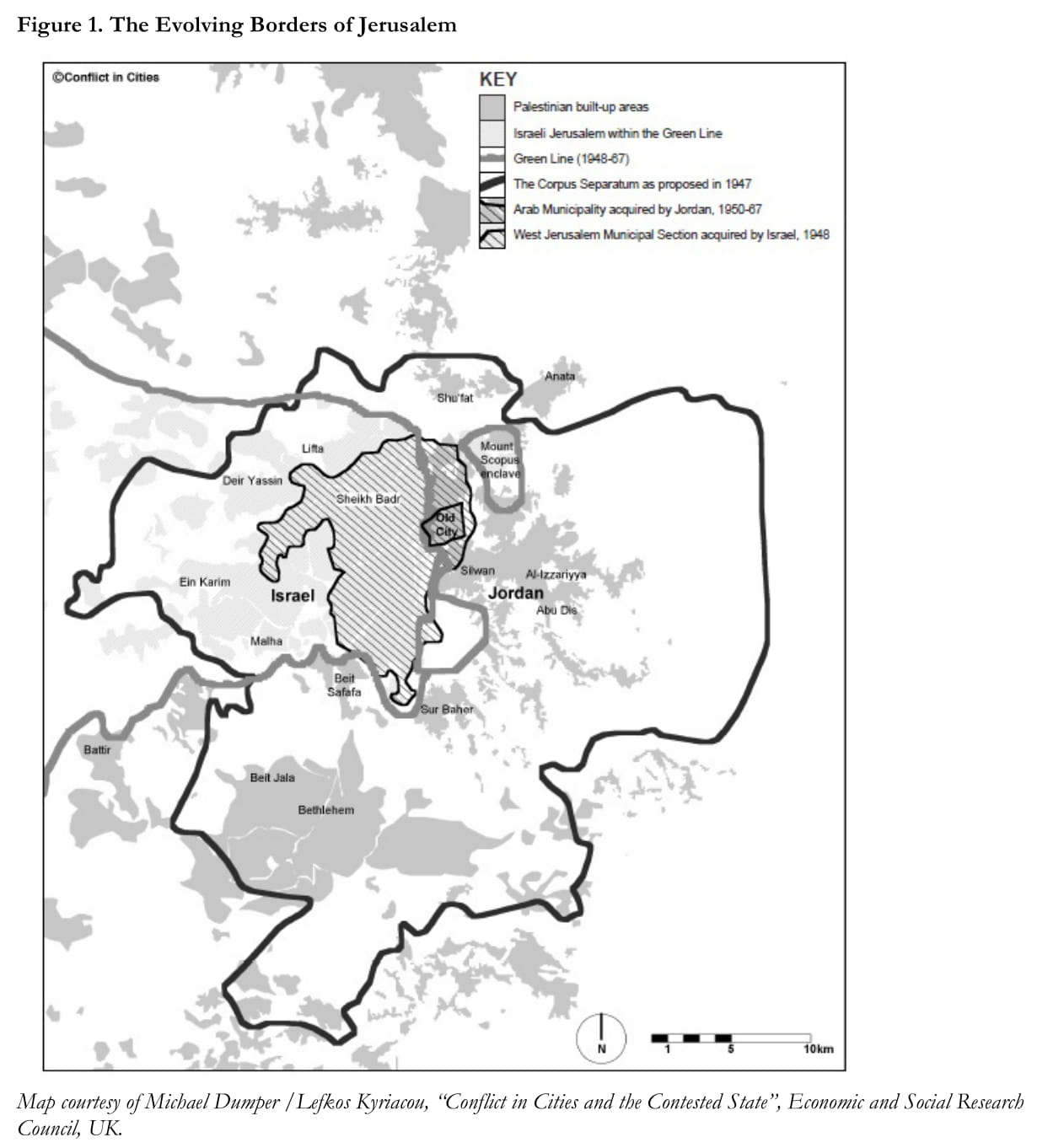

By the end of the 1940s, the British Mandate proved impossible to sustain in the face of growing Jewish immigration and the clamouring of both Palestinian and Jewish communities for an independent state. In 1947, the United Nations proposed a partition of Palestine into three entities — a Jewish state, an Arab state and a temporary international zone for Jerusalem, known as the Corpus Separatum.

The international zone for Jerusalem was never established. Following the outbreak of fighting between the Palestinian Arab and Jewish communities, the British withdrew from Palestine in May 1948, and the city was divided between what became known as Israeli West Jerusalem and Palestinian East Jerusalem. This partitioning of Jerusalem was one of the most important developments in the city’s modern history.

It was a division that lasted 19 years until the Israeli takeover of East Jerusalem in 1967. It was also a division which has left its scars on the city to this day, where it is still possible to identify physical markers and architectural and cultural differences between the two sides of the city. The entire Palestinian population in the western neighbourhoods of Jerusalem fled to the eastern side. Similarly, all of the Jewish population in the Old City and in enclaves adjacent to the Old City fled to the areas held by the new state of Israel. The dividing line ran along the western edge of the Old City walls before curling back down towards the coast, which became the heartland of the new Israeli state. This became known as the famous “green line”. During this period of division, the municipal area of East Jerusalem fell under the control of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and was slightly enlarged to incorporate a number of villages. Similarly, a new Israeli municipality was established in West Jerusalem, also with new and larger borders.

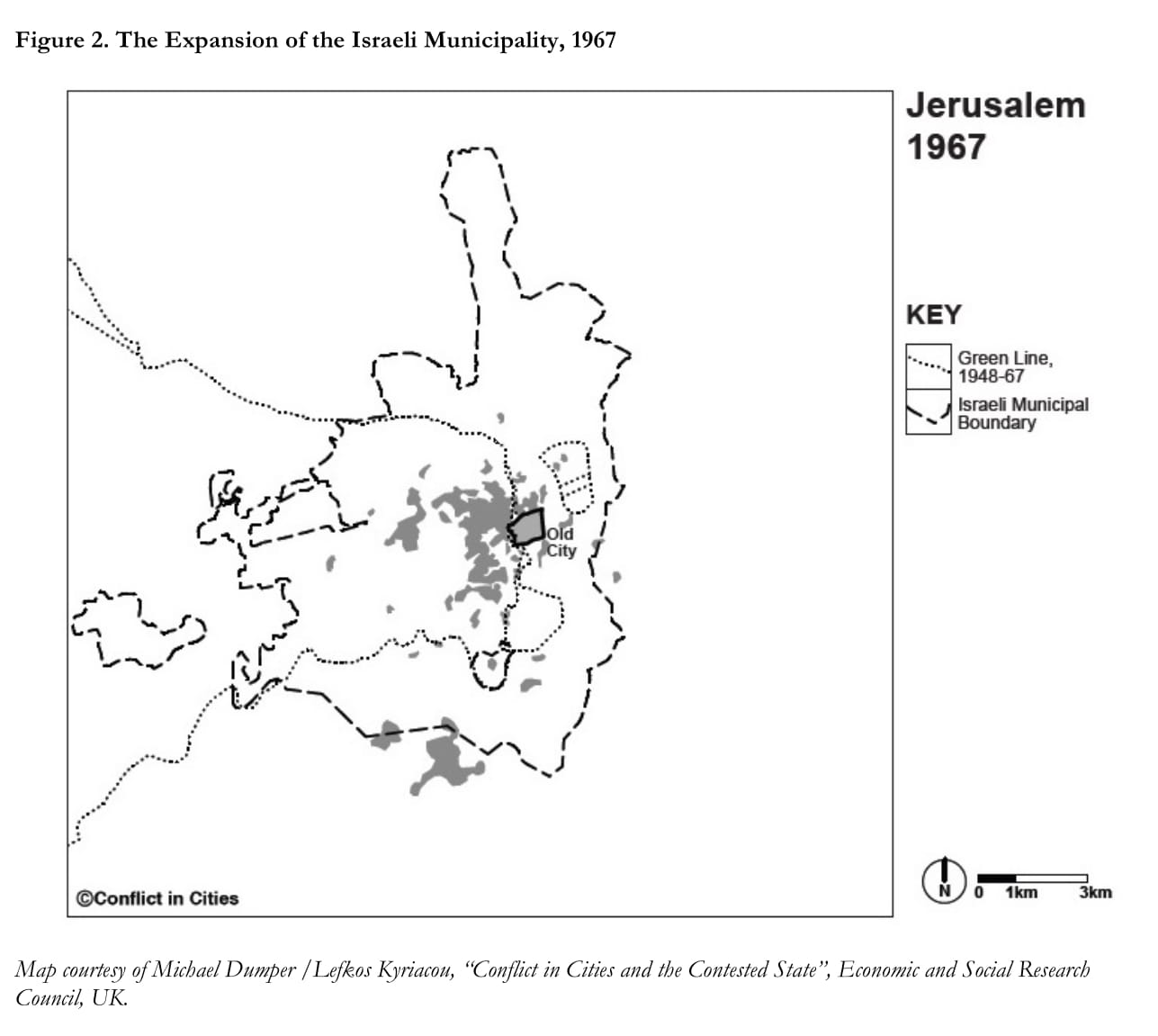

In 1967, Israel occupied the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, which ostensibly meant that a single polity was once again in charge of the whole city. The Israeli state rapidly moved to incorporate East Jerusalem and additional adjacent parts of the West Bank into a new and greatly enlarged Israeli Jerusalem municipal area. However, despite enormous investment in these acquired areas, not only did it fail to completely repair the slash running through the heart of the city, its policies also engendered a whole series of new divisions and sub-political borders in the city. It is at this point that one can see most clearly how Jerusalem became a city of many borders. Although there are many reasons for these Israeli policies, exploring the main ones should suffice to illustrate this broader pattern of fragmentation.

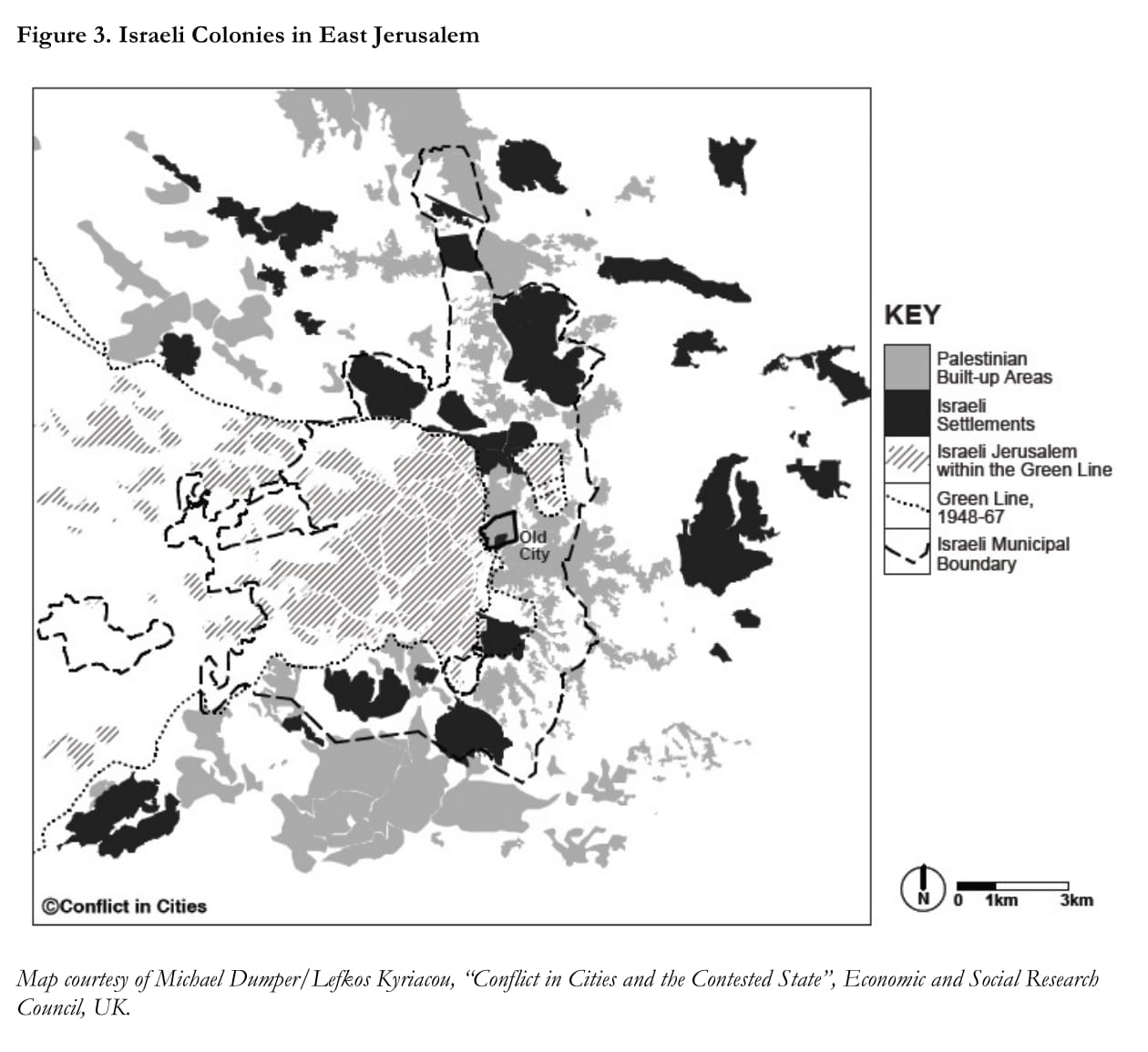

The first main issue is that of demography and residential segregation. Figure 3 shows that the implantation of Israeli settler colonies in East Jerusalem has been a huge and comprehensive exercise.

It was designed both to ensure the physical separation of East Jerusalem from its West Bank hinterland and to bind those colonies and the territory they are built upon to the Israeli state through infrastructure, services and a separate legal system. Putting aside the issue that, in the main, this was land which belonged to Palestinians or to non-Israeli institutions, the essential feature of these colonies is not just their often forbidding quasi-military configurations, but that they are legally reserved for Israeli Jews. Palestinian Arabs of East Jerusalem and even Palestinians with Israeli passports are not permitted to live in them. In one single policy action, the whole of East Jerusalem had been broken up into a collection of enclaves, creating a series of social, linguistic, religious, educational as well as political borders across a large part of the city. No decision has had a greater impact on the integrity of the city than this policy of residential segregation.

The second driver behind the fragmentation of Jerusalem is the Israeli quest for security in and around the city. Following the 1967 war, Israel was able to assert complete military dominance over the eastern parts of the city and its hinterland.[5] Military operations and terrorist attacks have been carried out by the different Palestinian military and political groups but these have been largely sporadic and easily quashed. There has also been widespread public disorder, notably during the two Palestinian intifadas (uprisings), stretching between 1987 and approximately 2006. Nevertheless, Israeli military dominance over East Jerusalem is not in doubt or under threat.

At the same time, Israeli security concerns and policing operations have created a dual security system, which further divides the eastern part of the city into enclaves. From 1967 until 1993, for example, a security border that ringed East Jerusalem was in place, but was barely congruent with the new municipal borders introduced in 1967. Checkpoints and barriers were placed at key access points to the city, which in some cases were well inside the municipal borders and in others, further out, depending on the topography and the security risks for the soldiers involved. From 1993 onwards, following a wave of attacks by Palestinian militants on Israeli soldiers and civilians, a barrier, also known as the “wall”, was erected. This “wall” ran between the Israeli colonies and the more outlying areas of Palestinian residence and bore little relation to the municipal borders of the city.

Thus, not only was East Jerusalem divided by policies of segregation, it was further divided by policies which sought to enhance the security of Israeli residents in East Jerusalem.

“Soft Borders”

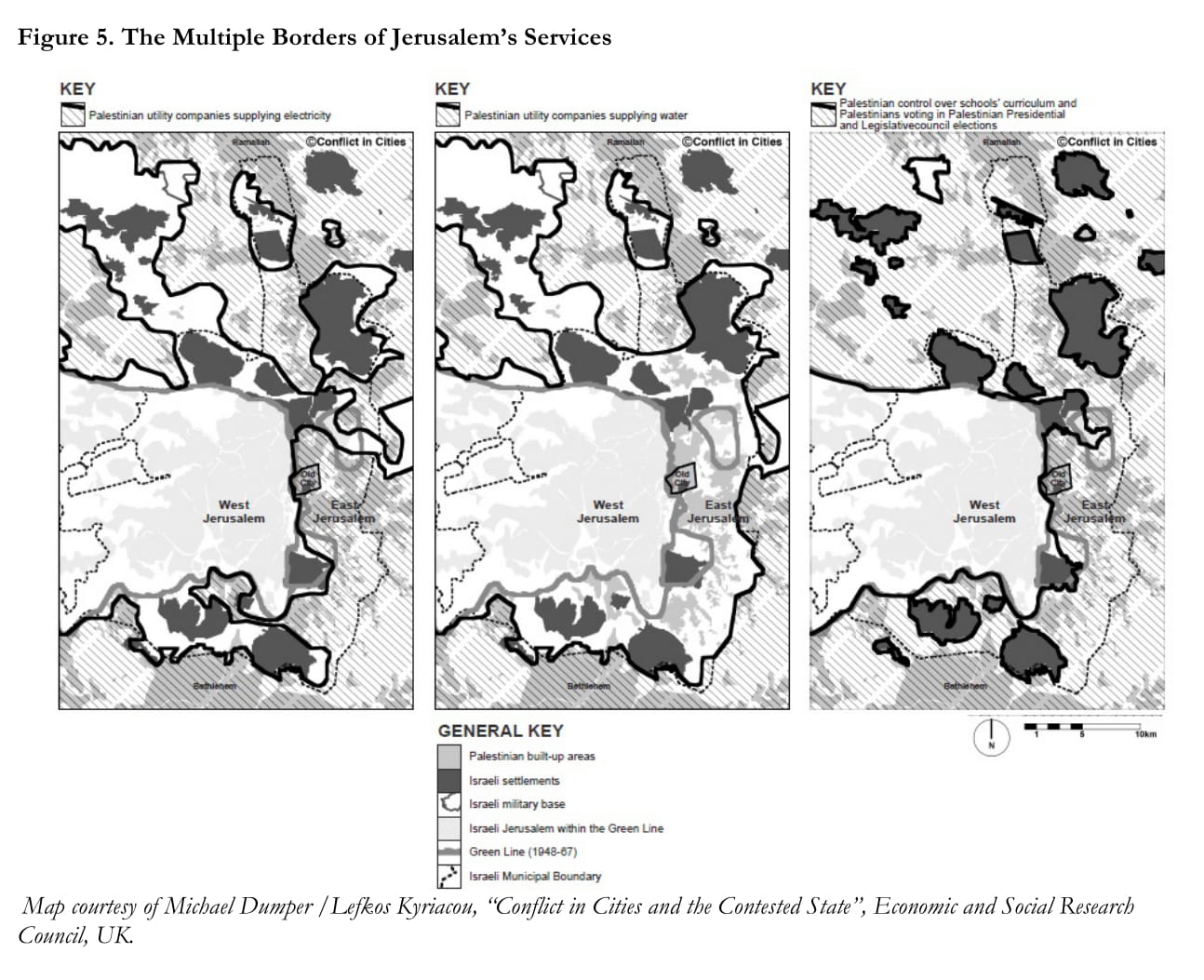

There are other examples which may not have had the same impact as the segregation and security policies mentioned above, but, nonetheless, have exacerbated the fragmentation those policies have brought to the city. These I refer to as the “soft borders” of the city. One example is that the water supplied to the northern Palestinian suburbs is piped in by the Palestinian-owned Ramallah Water Undertaking based in Ramallah. Similarly, electrical power in all Palestinian areas is supplied by the Palestinian-owned East Jerusalem Electricity Company. So, ironically, in the capital of the state of Israel, some key services are supplied by institutions associated with that state’s main opponent.

Another example of “soft borders” is in the realm of religion. As one might imagine in a city so replete with religious institutions and religious history, the various religious communities and their governing hierarchies play important roles in the way the city is governed. These are powerful institutions that constrain the ability of the state to exercise its full sovereignty and jurisdiction in Jerusalem. In the period after 1967, when Israel began its colonising activities and extended its rule over East Jerusalem, it made concessions to Muslim and Christian religious establishments, allowing them a significant degree of autonomy in administering their properties and their holy places. One should recall that significant parts of East Jerusalem and, in particular, the Old City, are owned and administered by churches or the Waqf Administration, an Islamic foundation. Since 1967, the Waqf Administration has continued to be funded by the Jordanian government, which also appoints most of the senior personnel. Thus, the Waqf Administration, a semi-autonomous administration and one of the largest employers in the city carrying out significant building works and communal activities in East Jerusalem, is simultaneously managed by the Jordanian government and staffed by personnel loyal to either the PLO or to Hamas — and right in the heart of territory that Israel is claiming as its capital. (We should also not forget here the role of the Jewish eruv, which is a barely visible border running along the tops of lampposts and high posts demarcating the area where orthodox Jews are permitted to carry out certain normal activities on the Sabbath, which they cannot do if they are not within this line. For haredi residents of Jerusalem it may be the most important border of all and constitutes the core of the city they claim!)

All these criss-crossing hard and soft borders combine to divide Jerusalem into small pieces. Enclaves and stretches of land or street, each operating under a different legal jurisdiction, different policing rules, different curricula, etc., sit adjacent or in close proximity to one other.

***

It is possible to compare Jerusalem with a number of other cities with religious conflicts, for example, Banaras in northern India and Lhasa in Tibet. In such comparisons, one can find evidence that religious conflicts in cities emerge when there are certain factors at play. These factors include the existence of two or more religious communities fighting for control over holy sites that are central to their faith and the presence of powerful clerical hierarchies that have sources of revenue independent of the state and strong international links either through a religious diaspora or through pilgrimage. Some religious conflicts are exacerbated by residential, educational and employment segregation and by policies which privilege one community above another. At the same time, religious conflicts can be ameliorated if the rule of law implemented by the sovereign power is recognised as broadly legitimate. Despite the rise of Hindu nationalist parties in India that have targeted mosques said to be built upon the ruins of Hindu temples, the legitimacy of the state itself is not in question. Opposition to Hindu maximalist claims proceeds broadly within the accepted legal framework.

In the Jerusalem case, we can clearly see how the absence of legitimacy from the Israeli state in East Jerusalem constantly undermines the authority of the Israeli state in the conflicts over the access to, and management of, the holy sites. In these conflicts, the Israeli state is seen by Palestinians, the Muslim and Arab world and more broadly by the international community as privileging the interests of Israeli Jews over those of Palestinian Arabs.

In these circumstances, many of the proposals to break the impasse between Israeli and Palestinian negotiators flounder on the question of the right of Israel to any claims to East Jerusalem in the first place. Taking just two of the many dozens of proposals on the table — the Geneva Initiative and the Jerusalem Old City Initiative — we can see some of the difficulties in coming to an agreement.

As one can see from these maps, for all their merits in trying to reconcile the positions of the two protagonists, the way that Jerusalem has evolved since 1967, with its patchwork of enclaves, has led to a series of proposed borders which are a security expert’s nightmare: on one hand, they consist of narrow necks or tongues of land, enclaved clusters of houses, long tunnels with bends, and bridges over strategically important roads, all of which will require a huge investment in surveillance systems and security personnel on the ground[6]; on the other hand, crucial elements such as sovereignty over key areas are deferred to a later date. I do not dismiss such urban security devices out of hand, but raise the challenges they present here as an illustration of how the many borders of Jerusalem render any movement on the future of the city extremely difficult.

***

This paper began by drawing attention to how the December 2017 declaration by the current US administration, through its unilateralism regarding the Palestinian claims to East Jerusalem, has deferred the resumption of negotiations. Reflecting on the two and a half decades of political stalemate since the Oslo Accords, we should ask ourselves: to what extent is the search for peace in the city in the current context a search for fool’s gold? Surely, we need to recognise that unless there is a dramatic shift in the current balance of power between Israel and the Palestinians, there can be little change in the ongoing low-intensity conflict situation? I would argue that this ongoing low-intensity conflict is based on a trajectory where Israel will gradually and steadily encroach upon non-Jewish holy sites and either gradually and steadily squeeze out the Palestinian population from East Jerusalem, or gradually and steadily absorb it into Israel as second-class residents.

At the same time, however, such an eventuality will not resolve the conflict, which will continue to fester. This is because although Israel can advance its position in East Jerusalem with relative impunity, it is not able to take more far-reaching steps to completely neutralise Palestine and the international community’s opposition to its advance. It is not able, for example, to act as ruthlessly as the Chinese government has in Lhasa, where the Tibetan Buddhist leadership, the religious institutions, and holy sites are controlled by the Chinese state. Israel has not yet been able to dismantle the religious institutions that constitute the Islamic and Christian presence and thus the Palestinian presence in East Jerusalem. Similarly, its internal political dynamics mean that the prospect of Israel succumbing to international and Palestinian pressure to return the Palestinian property which it has acquired in East Jerusalem and recognising Palestinian sovereignty there is equally remote. Such an impasse means that it is highly unlikely that there will be any semblance of a negotiated agreement over the city and the conflict will remain for the foreseeable future, producing spikes of sporadic violence that are hastily and temporarily managed, but ultimately not resolved.

***

Where does this leave countries like Singapore, lying in the middle of a region which will be affected by the continued impasse in Jerusalem and in the Palestine-Israel conflict? First, conferences such as the conference on Jerusalem organised by the Middle East Institute play a crucial role in keeping policymakers and the general public informed of possible instability that may emanate from the Middle East and affect its wider backyard. One of the least welcome aspects of the conflict has been the way that ill-informed interventions by third parties have exacerbated and made much more complicated the attempts of the key actors in the conflict to come to an agreement. By supporting research and disseminating information on the topic, Singapore can contribute to a greater understanding of its complexity.

Second, Singapore is well-known for its close adherence to the rule of law in international relations, including on the Palestinian issue. By encouraging an agreement between the two parties to the conflict that is equitable and just, Singapore will find itself on higher moral ground when it calls for similar adherence to the rule of law in regional tensions closer to home and in situations where there is an asymmetrical balance of power.

Third, the example of Singapore as a multi-ethnic and multi-confessional society should not be undervalued or overlooked. The civic peace that has prevailed on the island since the shock of 1969 has not been achieved easily. There have been mistakes and disappointments along the way, but the lesson that the state should take an active role in creating policies and a public discourse that is inclusive and respectful of difference is an important one that can be fruitfully shared with allies, neighbours and interested parties in the Middle East. As we can see, studying Jerusalem raises all these issues and opens up so many avenues for debate and discussion, which are relevant to Singapore.

About the Author

Professor Michael Dumper, an alumnus of St Andrew’s School, Singapore (1964–1968), is Professor in Middle East Politics at the University of Exeter, UK. In addition to his most recent edited book, Contested Holy Cities: Urban Dimensions of Religious Conflicts (Routledge, 2019), his works include Jerusalem Unbound: Geography, History and the Future of the Holy City (Columbia University Press, 2014), The Politics of Sacred Space: The Old City of Jerusalem and the Middle East Conflict (Lynne Rienner, 2002) and The Politics of Jerusalem Since 1967 (Columbia University Press, 1997). His forthcoming book Power, Piety and People: Holy Cities in the 21st Century compares religious conflicts in cities in Europe, Asia and the Middle East, and will be published by Columbia University Press in 2020. He has acted as a consultant on Middle East politics for the British and Canadian governments, as well as for the United Nations and the European Union.

Image caption: View of Jerusalem. Photo: Andrew Shiva, shared on Wikipedia.

Footnotes

[1] At night, when the traffic is light, it is possible to drive from the Israeli separation wall on the eastern edge to the western suburbs in less than 15 minutes. Jerusalem has a population of less than 1 million people.

[2] Michael Dumper, Jerusalem Unbound: Geography, History and the Future of the Holy City (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014), 99.

[3] The key texts that deal with the United States and its policies on Jerusalem are: S Adler, “The United States and the Jerusalem issue, Middle East Review XVII (4; Summer, 1985); J Boudreault and Y Salaam, “The Status of Jerusalem”, IPS US Official Statement Series, Institute for Palestine Studies, Washington DC, 1992; Y Feintuch, US Policy in Jerusalem (New York: Greenwood Press, 1987); D Neff, “US Policy on Jerusalem”, Journal of Palestine Studies 89 (1993), 20-45; and S Slonim, “The United States and the Status of Jerusalem, 1947-1984”, Israel Law Review 19, 179-252. For a summary of US policy on Jerusalem see Michael Dumper, Jerusalem Unbound, 176-180.

[4] “Recognizing Jerusalem as the Capital of the State of Israel and Relocating the United States Embassy to Israel to Jerusalem, Proclamation 9683 of December 6, 2017”, Presidential Documents, [US] Federal Register 82 (236), 11 December 2017, 58,331, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2017-12-11/pdf/2017-26832.pdf#page=1

[5] For further details, see Michael Dumper, “Policing Divided Cities: Stabilization and Law Enforcement in Palestinian East Jerusalem”, International Affairs 89 (5; September 2013), 1,247-1,264.

[6] For example, it is not clear from the drawings included in the Geneva Initiative whether or not the border which is to run along the middle of Road 60, the main road leading out of Jerusalem northwards, is designed to be impermeable. Consisting of a low barrier and a narrow ditch, hidden by green shrubs, presumably to soften the visual impact of a border in this central location, I cannot imagine it offering much deterrent to a determined infiltrator despite the electronic surveillance. See Geneva Initiative, “Annex 05: Jerusalem — Urban Challenges and Planning Proposals”, 156-7, available online at https://geneva-accord.org/annexes-translations/