Iran is the linchpin of the Belt and Road Initiative’s overland component. This, coupled with the United States’ withdrawal from the JCPOA and the ongoing US-China trade war, gives Beijing more reason to cooperate with Iran.

By Kevjn Lim

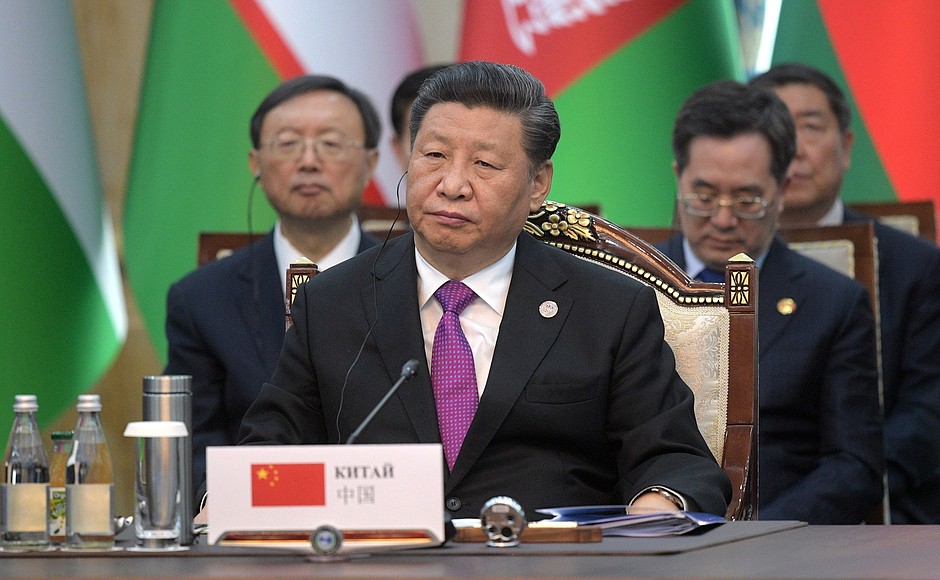

At the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in Bishkek, China’s Paramount Leader Xi Jinping assured Iranian President Hassan Rouhani he intended to promote steady development of bilateral strategic relations regardless of the changing circumstances. This comes amid thickening Iran-US tensions, a day after another two oil tankers near the Strait of Hormuz suffered sabotage attacks attributed by Washington to Iran. Having withdrawn from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the landmark nuclear agreement between Iran and six world powers, the Trump administration has progressively reinstated and even stepped up secondary sanctions for “maximum pressure” against Iran, which is in turn pushing both countries to the brink of armed conflict.

The statement’s setting isn’t insignificant. A Chinese and Russian co-led regional organization encompassing India, Pakistan and most of Central Asia, the SCO is widely viewed as a thinly-veiled attempt to balance against NATO and the US. Furthermore, China, Russia and Iran – currently an observer despite longtime requests for full membership – openly call for a more multipolar international order.

Xi Jinping was however referring to the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership both countries jointly announced during his January 2016 visit to Tehran right after the JCPOA came into effect. This also entailed medium-term plans to raise bilateral trade to USD 600 billion and enhance security cooperation including joint naval exercises, reflecting Iran’s importance for regional security and China’s growing emphasis on blue-water capabilities.

US sanctions have meanwhile made dents, raising questions about China’s strategic commitment to Iran. While China remains Iran’s top oil client, Chinese state refiners have preferred prudence, buying Iranian crude at lower volumes and even briefly suspending purchases twice in recent months, including when US sanction waivers expired in May. Sanctions likewise risk rocking Chinese involvement in Iran’s upstream energy sector, already beset with issues such as sub-par Chinese technology.

Strategic cooperation is however quietly and more robustly underway on the ground. While Iranian oil exports matter more to Tehran than to Beijing, Iranian soil and specifically railways cut to the heart of China’s 21st century grand strategy.

Iran is the linchpin of the Belt Road Initiative’s (BRI) overland component – a broad swathe of Eurasia Halford MacKinder called the ‘geographical pivot of history’ – and the only land bridge with access to Europe, the Middle East and Africa, Central Asia and the Caucasus, Southwest Asia and the Indian Ocean. Russian territory offers a longer skirt-around and hosts existing railways connecting China and Europe, but Moscow is a potential competitor as China’s military capabilities rise alongside its economic clout. Indeed, Iran also facilitates the International North-South Transport Corridor linking Russia to India, a fact the Commonwealth of Independent States recognized by recently upgrading Iran’s observer status to permanent membership of its Council for Rail Transport.

As I argued before, all this endows Iran with a significance far surpassing its size or capabilities. The historical Silk Roads linked Chinese and Persian bazaars, and Iran often controlled onward trade flows between Eurasia and the Western and Eastern Roman Empires. In 1992, then President Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani called Iran the “crossroad of the world” and asserted that “whoever wants to rule the world can never ignore it”.

According to the American Enterprise Institute’s China Global Investment Tracker, China’s overseas transport-sector investments between 2005-2018 totalled USD 363 billion, superseded only by energy-sector investments. In Iran, out of USD $27 billion in total, China has invested USD 6.3 billion in transport, a third of it last year alone when Iran’s economy contracted. Between China and the Mediterranean excluding Pakistan, Chinese transport-sector investments are highest in Iran, more than even Kazakhstan (USD 3.1 billion), Israel (USD 2.4 billion), Turkey (USD 2.3 billion) and Russia (USD 2.1 billion). While investment levels also factor in considerations such as the state of existing infrastructure and alternative sources of financing, Iran’s figures clearly hint at its significance within Beijing’s revived Silk Road.

China’s overseas railway projects serve three main purposes. First, they absorb part of the country’s excess industrial capacity. Second, direct railway linkages stimulate trade, notwithstanding perceptions of Chinese goods envassalling Iran’s market. According to International Monetary Fund data, China-Iran merchandise trade last year amounted to USD 30.6 billion, 26 percent of Iran’s total trade. Iran exported twice more to China than to the entire EU and imported as much from China as from the EU. Despite fluctuations, bilateral trade remains strong. Third, railways augment connectivity with China’s great abroad. In case of conflict, connectivity facilitates overland force projection.

China’s infrastructural footprint first took form in the 1990s during Iran’s post-war reconstruction, far before BRI’s official announcement. CITIC group for instance built Tehran’s Metro System, the extension and maintenance of which Chinese companies were still a part of in late 2016. After the JCPOA, Chinese entities returned in force while Europe hesitated. Three weeks after Xi’s Tehran visit in 2016, a freight train from Yiwu, Zhejiang province using existing tracks reached Tehran within 14 days, the first such trip ever made. That September, a second freight train reached Tehran from Yinchuan, Ningxia province. In December 2017, a freight train similarly inaugurated the route connecting Changsha, Hunan province, again with the Iranian capital. Barely after Washington withdrew from the JCPOA, a freight train carried sunflower seeds from Bayannur, Inner Mongolia, to Tehran. Four months later, another train left Inner Mongolia for Bam in southeast Iran.

All this rolling stock glides through Xinjiang Province and Turkic Central Asia to the Iranian Plateau. Two main lines currently exist. The first, inaugurated in 2011 at the height of Iran sanctions, transits Kazakhstan (and a small stretch of Kyrgyzstan), Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan before entering Iran through Sarakhs. The second, opened in late 2014, transits Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan via Inche-Burun. A third route suffers from poor infrastructure particularly in mountainous Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, where Chinese transport-related investments have similarly been paltry. But the trains don’t just stop in Iran, and instead mainly branch out towards the Persian Gulf and through Turkey and Azerbaijan, westwards.

Inside Iran, to smoothen connectivity farther afield, Chinese firms among others are adjusting track gauges, constructing new lines and upgrading existing ones, dovetailing with Iran’s current Five-Year Development Plan. As of February, Iran had 11,226km of rail tracks and is planning to expand its network to 25,000km, of which 7,500km are currently under construction, all of which in turn requires some USD 25 billion in investment. In July 2017, the Export-Import Bank of China granted a USD 1.5 billion loan for the electrification of the high-speed Tehran-Mashhad railway by China National Machinery Import and Export Corporation. Since Central Asian lines link to Iran via Turkmenistan, this route is crucial for east-west transit. In September 2017, CITIC, China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China reportedly agreed on USD 35 billion in credit and contracts for BRI-related projects in Iran, which include transport.

In March 2018, Sinomach signed a USD 845 million contract to build a railway connecting Tehran, Hamedan and Sanandaj, and Chinese companies have signed contracts or plan to construct others including the Kermanshah-Khosravi and Shiraz-Farashband extensions. And just this past February, an Iranian official announced that with European contractors getting cold feet over US sanctions, China was now left to finance and help Iran finish constructing the 410km Tehran-Qom-Esfahan high-speed train. Chinese companies unlike many western counterparts in the Trump era are better positioned to secure critical sovereign credit.

Though Iran may ill-afford to lose China as oil client, it has plenty to gain from China’s overland Silk Road, especially if Tehran seeks to steer its economy away from hydrocarbons. Bilateral strategic cooperation in this regard improves Iran’s transit and economic potential, and mitigates its physical and political isolation. If China – the only permanent UN Security Council member enjoying good relations with Iran, Israel and Saudi Arabia without necessarily being perceived as biased – steps up to the challenge, it might even help stabilize the Middle East. While Iran controls the more important of the BRI’s two overland bridges, Israel’s prospective Red-Med transit corridor linking Eilat on the Red Sea to Ashdod on the Mediterranean, if ever realized (slated to be built by China Communications Construction Company), would constitute the key secondary route complementing the Suez Canal along the BRI’s maritime expanse. What BRI means for both regional adversaries, and the roles they play within give China powerful, positive leverage towards conflict mitigation. Cognizant of BRI’s potential, Rouhani himself has specifically suggested enhancing lasting, strategic relations with China via infrastructural development.

The Trump administration’s unilateral withdrawal from the JCPOA in May 2018 and the ongoing US-China trade war give Beijing more reason to cooperate with Iran. A security alliance including within the SCO’s context remains politically fraught, contradicting Iran’s revolutionary claims to independence and potentially dragging Beijing off balance. Similarly, China’s increasingly diversified energy sources lower the political costs of reducing (if not altogether axing) Iranian crude imports, faced with what it views as illegitimate US pressure. Meanwhile, where both parties will likely find it slightly easier to cooperate is in Iran’s transit topography. If Beijing leverages it right, the iron logic underlying its Silk Road and Iran’s (and Israel’s) place in it could, against much Western intuition, even go some way in generating diplomatic capital, a critical commodity in tense times.

About the author

Kevjn Lim is a PhD researcher at Tel Aviv University’s School of Political Science, Government and International Affairs, and consultant analyst with IHS Markit.