States in the Middle East today are coming together not on the basis of shared sectarian or ideological lines. Rather, they are coalescing along two rival lines of alliance: (1) a Northern Tier that connects Iran and Turkey to Russia and Central Asia and (2) a Southern Tier that ties the Arabian Peninsula to coastal South Asia, the Horn of Africa, and the southern Mediterranean. Conflicts and rivalries in the Middle East, when seen along these two lines, reveal a clear, operative rationale capable of piercing through the smoke of burning towns and the tangled web of relations that otherwise paint an image of disorder in the region. If these two alliances solidify into blocs, will their rivalries intensify, pulling neighbouring states into proxy wars? Or will they step back to conclude that good fences make good neighbours, divide the region between them, and calm down the countries caught in between? How they handle their rivalries will have consequences for how China’s Belt and Road Intitiative may pass through or bypass them.

By Serkan Yolaçan

The Middle East today looks chaotic. The ongoing wars in Syria, Yemen, and Libya have each spawned a web of friends and foes on top of old enmities and rivalries in the region. Caught up in these webs, political leaders often make puzzling geopolitical moves that appear to follow a sectarian logic in one moment while defying it in the next. Differences in religion, ideology, and political system in the Middle East help little in navigating its ever-changing political landscape, while any fleeting glimpse of a regional order quickly dissolves in its inexorable anti-Westphalian politics.

The chaos, however, contains an order that becomes apparent when we re-imagine the Middle East by first expanding it to include adjacent countries in West Asia and then dividing it along a north–south axis. States in the Middle East today are coming together not on the basis of shared sectarian or ideological lines. Rather, they are coalescing along two rival lines of alliance: (1) a Northern Tier that connects Iran and Turkey to Russia and Central Asia and (2) a Southern Tier that ties the Arabian Peninsula to coastal South Asia, the Horn of Africa, and the southern Mediterranean. Conflicts and rivalries in the Middle East, when seen along these two lines, reveal a clear, operative rationale capable of piercing through the smoke of burning towns and the tangled web of politics that otherwise paint an image of disorder in the region. But what are these alliances, and why do they map out geographically?

Partial Solutions

The Northern Tier comes into clear view in the Kazakh capital, Astana, where the foreign ministers of Iran, Turkey, and Russia have been regularly meeting to broker a peace in Syria. This trilateral dialogue, known as the Astana talks, was ushered in by a rapid dive in Turkish-American relations, which has drawn Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan closer to his counterparts in Russia and Iran. The three presidents, strained by their failing ties with Washington, have begun to tone down their mutual differences to find much needed additional strength in one another.

Though their collaboration does not imply a convergence of interests, the three leaders are keen to learn how to pursue diverging agendas without stepping on each other’s toes. The key to such a delicate dance, as they seem to have discovered, is to proceed with partial solutions to big problems, one step at a time. Let not the perfect be the enemy of the good, as they say. In contrast to total solutions, whose high stakes can cause gridlock, partial solutions raise the prospect of agreement by lowering the stakes for all parties.

The efficacy of partial solutions was demonstrated in the Syrian province of Idlib, the last standing territory of the Syrian opposition. There, a human disaster was prevented by a last-minute agreement between Erdogan and Russian President Vladimir Putin in Sochi to create a demilitarised zone, a decision endorsed by Tehran as well.[1] By compromising with one another over Syria, the Astana group managed to have a collective say in that country’s future. In fact, they recently shook hands on the composition of a committee to write a new constitution for post-war Syria.[2] With the withdrawal of American forces from Syria, the Astana group will effectively be the sole political guarantor of the Syrian peace process.

Old Neighbours

Russia, Iran, and Turkey constitute the backbone of what we call the Northern Tier. As long-time neighbours, these three former empires share a long history of imperial competition and emulation. Although their rivalries at times played up sectarian differences such as the Shi’a–Sunni divide, policing of these identities was neither consistent nor absolute. The three imperial neighbours had ethno-linguistic and religious communities straddling their domains, and these cross-border ties remain today. By using these ties, the three states are able to reach out to populations abroad and create cultural and economic hinterlands beyond their sovereign domains.

A distinguishing feature of the Astana group, then, is their ability to punch above their weight by partnering with communities that harbour transborder sentiments and resources. Their imperial pasts, which offer inspiring symbols and moral narratives, are hardly incidental to the process. Narratives and symbols help these powers to cast their commercial and military ventures abroad in terms not only of national security but also of historical and moral obligation. Russia’s annexation of Crimea, for instance, would not have unfolded so smoothly if it were not for the pro-Russian sentiments of the Crimean majority and the Kremlin’s ability to capture those sentiments in a moral frame by resurrecting the historical term Novorossiya or “New Russia.” It was not merely a military affair.

Iran and Turkey have shown similar capabilities in the recent past. Following the US invasion of Iraq, Iran successfully established a zone of influence stretching from Iraq to Lebanon by partnering with transnational Shi’a networks of militias, Islamic law experts or mujtahids, and pilgrims. Shrines of Imam Hussain in Iraq and his sister Zainab in Syria were important symbols in mobilising public support for the expeditionary operations of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards in these countries. Iran’s Shi’a revivalism was paralleled by Turkey’s neo-Ottomanism, a term used to describe the country’s active foreign policy under Erdogan. In partnership with diasporic religious communities, such as the one led by Fethullah Gulen, Turkey stepped up its diplomatic and business engagements in the region and elsewhere, and found the moral ammunition for its outward-facing activism in the many episodes and places of Ottoman history.

Strongman Leaders

The warming of relations among these old neighbours owes a great deal to their strong leaders. This point is especially true for Turkey and Russia, where the leaders’ firm grip on domestic politics brings them confidence and agility in their foreign relations even if it feels suffocating at home. Unlike institutionalised states, these strongmen embodying their own states can make unexpected U-turns or reach last-minute deals without any fear of a major domestic backlash. This strongman capability helps explain the Astana group’s ability to make rapid progress through partial solutions to problems on which they disagree.

Such elastic diplomacy, driven by strong leaders and partial solutions, has emboldened other leaders to come in and capitalise on the collaborative atmosphere that prevailed in the past two years. The Kazakh president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, is one of them. Soon after successfully mediating between Erdogan and Putin in the wake of the November 2015 Turkish–Russian jet crisis,[3] he turned the Kazakh capital into a neutral ground for the three powers to negotiate over Syria. And, much to the surprise of many, the Astana process has proved to be much more effective than the UN and US-backed Geneva peace process that produced little more than a blame game.

Another leader who is riding the tide is the Azerbaijani president, Ilham Aliyev, who has been stepping up his economic and diplomatic engagements in all three directions. In 2016, he brought Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani, and Putin to Baku, where they discussed matters of security, energy, and transportation infrastructure across the Caspian. Last year Aliyev was in Ankara for the inauguration of the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) that transports Caspian gas to Europe via Georgia and Turkey. The pipeline is important as it may be a harbinger of things to come in the Northern Tier. For one, the project is likely to extend into Iran, linking its natural gas supplies to the European market.[4] Reportedly, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan are being lobbied to join in too.

It is no stretch of the imagination to see these energy routes as potential extensions of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that looks to connect East and West Asia via Central Asia. A big obstacle in the BRI’s path was already removed in August 2018 when the decades-long dispute over the legal status of the Caspian was partially settled, allowing for the laying of pipelines on its seabed. The landmark deal among the five coastal states was achieved thanks to their leaders’ shared commitment to focus on the low-stakes aspects of the dispute while leaving the thorny issue of how to split up the hydrocarbon-rich subsoil territory to future bilateral negotiations. The resulting convention was a big win for strongmen pragmatism in foreign relations and their “partial solutions” approach to entrenched conflicts.

The Two Wings

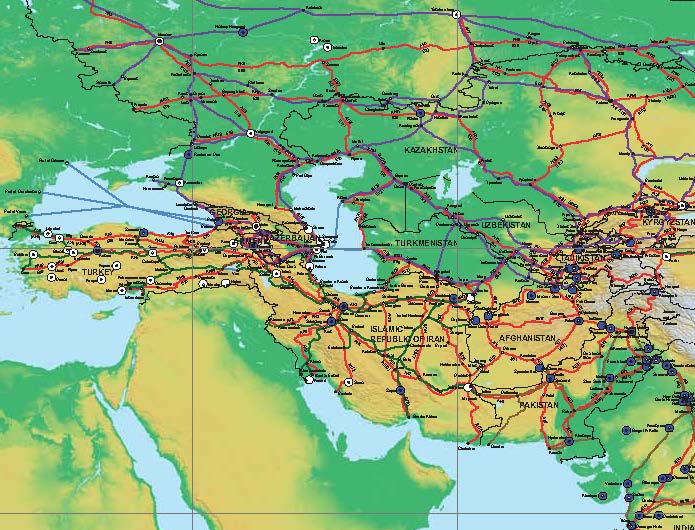

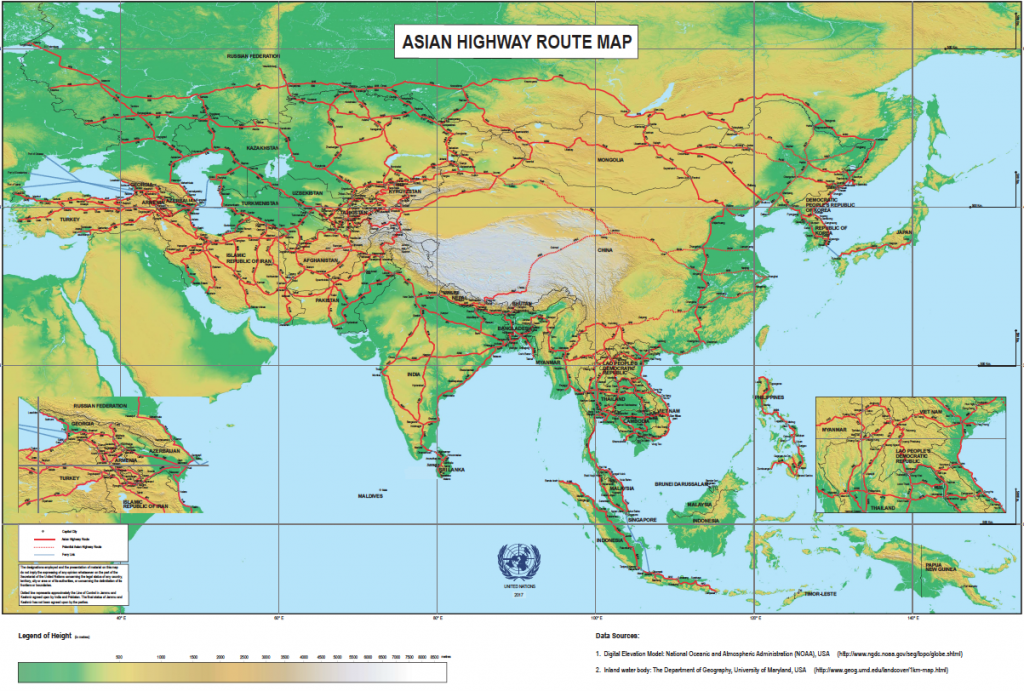

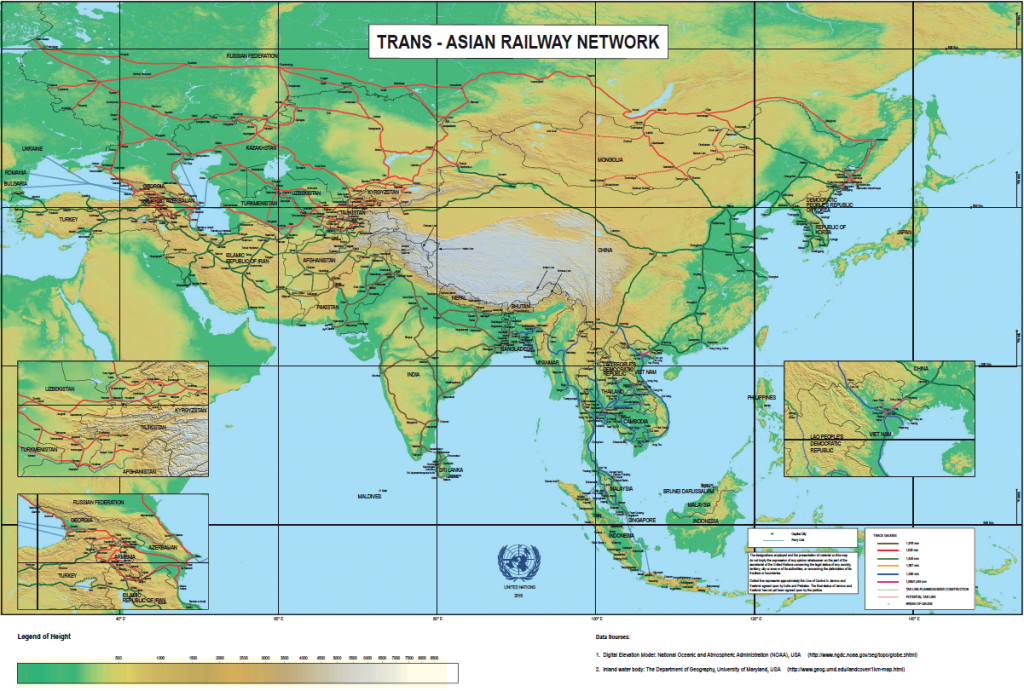

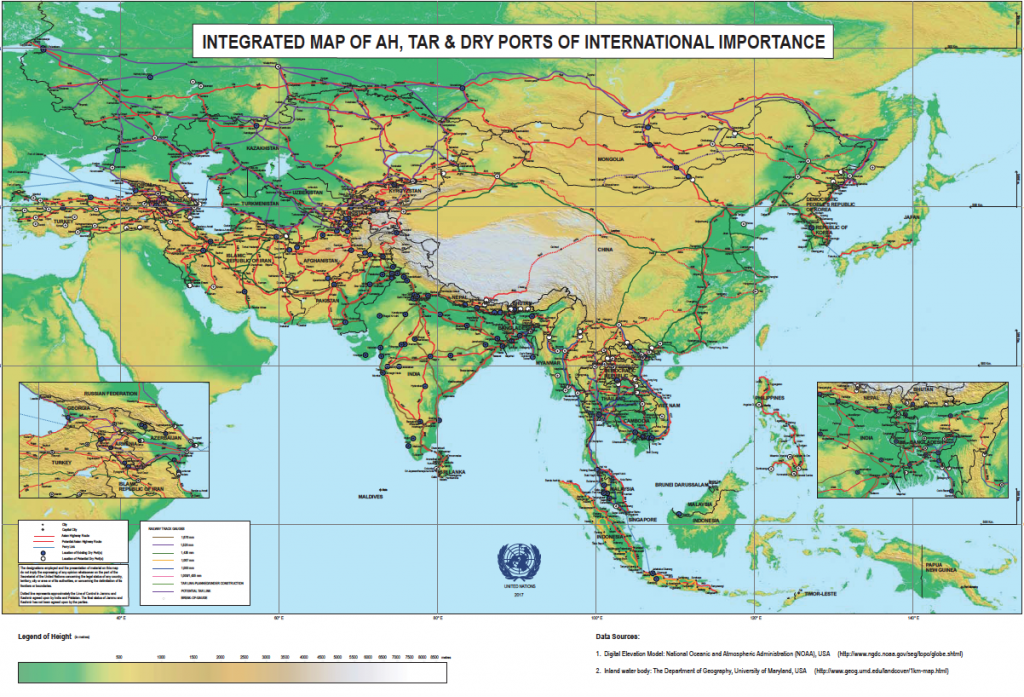

With the Caspian gridlock resolved, we may see the proliferation of energy routes across the Northern Tier, tying it to the markets in China and the European Union on each end. Pipelines underground are only half the story. Iran, Turkey, and Russia, whose economies are in dire straits, stand to gain from the Trans-Asian network of highways, railroads and dry ports that connect them to their more affluent neighbours in Europe and East Asia.

This broader commercial infrastructure and its further development incentivise leaders in Europe and Asia to keep the doors open to the Northern Tier countries despite political disagreements, past conflicts, or economic sanctions by the United States. When US President Donald Trump threatened Turkey with sanctions in the summer of 2018, for instance, it was German Chancellor Angela Merkel who reached out to Erdogan, “offering Germany’s credibility to avert a spillover of economic turmoil.”[5] Similarly, the US-imposed sanctions on Russia and the new tariffs on Chinese goods drew Putin and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, closer together. The two voiced interest in using national currencies in reciprocal payments while flipping pancakes in Vladivostok last year.[6] Last but not least, all of the above countries reiterated their support for the Iran nuclear deal even after Trump’s decision to withdraw from it. In short, the Astana group draws additional strength from China and the European Union — the two wings of the Northern Tier — to counter Washington’s volatile stance against them.

Fig 1. Asian Highway Route Map

Source: United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and Pacific, https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/AH-map-GIS.pdf

Fig. 2. Trans-Asian Railway Network

Source: United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and Pacific, https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/TAR%20map_1Nov2016.pdf

Fig. 3. Integrated Map of the Asian Highway and Trans-Asian Railways Networks and Dry Ports of International Importance

Source: United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and Pacific, https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/AH-TAR-DryPorts-Map.pdf

A Southern Tier?

What does the Northern Tier mean for the rest of the Middle East? What kind of a regional order does it imply? The spectre of the Astana group’s growing clout in the region has already alerted Gulf leaders to counteract this northerly force by cementing their own alliances in the south. The Saudi Crown Prince, Mohammad bin Salman (MBS), who signed multi-billion dollar agreements with Egypt and charmed American notables from coast to coast, has been leading the way.[7] His recently announced plan to “bring several states lining the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden into a bloc to improve trade and maritime navigation” is another step in the same direction.[8] These moves help consolidate what we may call the Southern Tier, which comes into view in the seas surrounding the Arabian Peninsula.

The Southern Tier first crystallised in the Persian Gulf, where a total blockade on Qatar by a Saudi-led coalition in June 2017 created a rift in the region, pushing Qatar closer to Turkey and Iran while laying bare a tightening partnership among Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The Saudi–Emirati partnership extends into the war in Yemen, where the Emiratis took control of strategic outposts on the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait connecting the Gulf of Aden to the Red Sea. What has turned into a real quagmire for the Saudis became an opportunity for the UAE leadership, who are using their presence in Yemen to assert control over some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes.

What pipelines and dry ports are to the Northern Tier, maritime routes and port cities are to the Southern Tier. The UAE’s DP World, a global port operator, has been quietly laying that maritime infrastructure through port-related company acquisitions, terminal projects, and counter-piracy initiatives that comprise navies from around the world, including that of Singapore. The UAE’s maritime ambitions, which are a major impetus in its competition with Qatar, place the Southern Tier within an oceanic space, primarily between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean, but also across the globe.

The prospects of the maritime Southern Tier are not lost on their neighbours in the Horn of Africa, who have already moved to claim their share. Landlocked Ethiopia has just found an outlet to this busy maritime corridor by making peace with its long-time adversary, Eritrea — the deal was brokered by the Saudis in Jeddah. Geographic proximity and a sense of shared fate have come into sharp focus in this part of the world just as it has in the Northern Tier. This partly explains why the new alliances map out geographically.

On land, the Southern Tier countries are propelled by their anti-Iran and anti-Muslim Brotherhood sentiments. While Turkey, Iran, and Qatar are at home with political Islam, the Saudi–Emirati–Egypt alliance sees it as an existential threat to their regimes. This ideological rift is essential because while the Northern Tier countries, particularly Iran and Turkey, can mobilise volunteer groups beyond their borders through ideological, religious, and imperial symbols (and this on top of their large armies), their Southern Tier counterparts lack such cross-border volunteer energy.[9] Instead, they mostly rely on airstrikes and mercenaries. This is most visible in Yemen, where the Saudis are trying to win a war in their backyard primarily through airstrikes, while the Iranians, with little direct role in Yemen, gain a lot of leverage by inspiring the Houthi leadership’s worldview.[10] The limited ground capability of the Southern Tier is also evident in Aden, where the Emirati troops are essentially a mercenary force primarily drawn from Sudan.[11]

What underpins these airstrikes and mercenary forces is a big pot of money. If the Northern Tier are led by former empires with large armies and ground capability, the Southern Tier is driven by new states with lots of money. The only outliers in this categorisation are Egypt and Qatar. Whereas Egypt harbours a potential reserve army for the Southern Tier (though that potential has not materialised yet — Egypt refused to provide any troops for the Saudi–UAE forces in Yemen), Qatar brings money to the Northern Tier, as evinced by its US$15 billion investment offer to Turkey in the wake of the Turkish Lira’s plunge.

***

The emergent new order in the Middle East outlined here comes into view on a West Asian scale, stretching from Russia and Central Asia to the Arabian Sea and the Horn of Africa. West Asia sits in the middle of the Old World, between Europe and East Asia. It was through this middle chunk that the West went east in the past, and it is through there that the East is going west today. A two-tiered West Asia, if it solidifies, is likely to have far-reaching consequences for what has been called the Asian Century, and the most obvious one is this: the future integration of the Old World along two parallel tracks. While one path would connect Europe and Asia through overland routes along a contiguous geography, the other path would follow the Indian Ocean littoral, connecting the Red Sea and the Arabian Peninsula to East Africa and South and Southeast Asia, and tie up with the West via the Mediterranean and the Atlantic.

This picture roughly coincides with the maritime and overland routes of China’s BRI going west. In the 19th century, when the British wanted to build telegraph lines going east, they were faced with a dilemma. If they were to lay the cables under water, it would require a big investment initially, but that disadvantage would be offset in the long run by low management costs, thanks to British maritime control. It would be much cheaper to lay the cables overland instead, but then the management costs would be much higher as it was more difficult to provide security overland across several imperial borders and conflict zones. Having tried the overland option, the British eventually switched to the sea, creating the submarine telegraph cables that proved critical for their imperial control across far-flung colonies. Today, China going west faces similar infrastructural and security concerns. Unlike the British in the 19th century, China in the 21st century may not have to choose between land and sea because the possible emergence of a Northern Tier across West Asia may create an overland strip of peace and order stretching across and connecting Russia, Central Asia, Iran, and Turkey into Europe.

***

The upcoming issues of Insights in this series offer a closer examination of the Northern Tier as an emerging axis of Eurasian integration, and explore its historical conditions and future possibilities as an interconnected political landscape across West Asia. An article by Brandon Friedman, the next in the series, provides a valuable historical reminder: the Northern Tier has a genealogy. Initially comprising Turkey, Iran, and Afghanistan, the Northern Tier was conceived in the 1920s as a buffer zone between the British and the Soviet Union and continued to be an arena of big power competition during the Cold War, with the United States replacing the British as the primary Soviet foe. Although the Soviet collapse ended Moscow’s influence on the Northern Tier, leaving it open to the competing claims of the West and the Islamists, Russia under Putin has made a comeback recently after years of building confidence in the former Soviet orbit.

“Russia’s moment in West Asia,” as Friedman calls it, extends well beyond the Northern Tier. Moscow’s growing relations with the Gulf, which Li-Chen Sim will examine in a future article, is a case in point. Sim will show how the Kremlin is fashioning itself as an extra-regional arbitrator in the many conflicts of the Middle East from Yemen to Libya, by developing relations with the opposing sides to the same conflict. This is a strategy, she argues, that “Russia has already perfected in the former Soviet republics where it plays a significant role in entrenching multiple ‘frozen conflicts.’” This strategy allows Russia to build influence outmatching its resources.

As mentioned earlier, Iran and Turkey showed similar capabilities by partnering with or patronising transnational networks. However, the ideological overtones of their respective projects also drove a wedge between the two neighbours. Sabri Ateş will offer a cautionary tale of lurking sectarianism in Turkish–Iranian relations by taking us back to the Ottoman–Safavid rivalry of the 16th century. Ateş also will show us a way out by presenting the gradual secularisation of relations since the 19th century as another, and indeed a more desirable, path forward for the two states.

Serik Orazgaliyev will take us to the Caspian Basin, where developments in the Northern Tier come into sharp focus. The resolution of the Caspian dispute there gives the post-Soviet republics of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan ample room to develop commercial and energy links in all directions at once. The Caspian region, already home to the Astana group, is likely to serve as their bridge to China.

Diplomacy and commerce are inextricably entangled along this northern corridor, and such entanglement brings to the fore mobile societies, whose expansive economies and solidarity networks offer alternative avenues for resolving political conflicts and brokering trade deals. Magnus Marsden will present diasporic Afghan merchants as one such society and will discuss their transnational networks as channels of informal diplomacy across the Northern Tier and beyond.

The series will conclude with Nisha Mathew’s article on the UAE–Saudi alliance, whose maritime ambitions are re-ordering the Middle East from the south, widening its catchment area into the littoral areas of South Asia and East Africa. She illustrates how the two oil-rich states, alarmed by the prospect of Iran’s re-integration into the international economy, have successfully reset traditional political alliances in the region with the backing of both the United States and Israel.

About the author

Serkan Yolaçan is a Research Fellow at the Middle East Institute. His research examines diasporic networks of business, religion, and education as conduits of social and political change in the Middle East and post-Soviet Asia. He is currently working on a book project that brings to light the role of the Azeri diaspora in connecting the modern histories of Iran, Turkey, and Russia. He holds a PhD in cultural anthropology from Duke University and a master’s in sociology and social anthropology from the Central European University.

Notes

[1] On his Twitter account, the Iranian foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, wrote: “Intensive responsible diplomacy over the last few weeks — pursued in my visits to Ankara & Damascus, followed by the Iran-Russia-Turkey Summit in Tehran and the meeting [in] Sochi — is succeeding to avert war in #Idlib with a firm commitment to fight extremist terror. Diplomacy works.”

[2] Patrick Wintour, “Russia, Turkey and Iran reach agreement on Syria committee,” The Guardian, December 19, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/dec/18/russia-turkey-and-iran-reach-agreement-on-syria-committee

[3] Murat Yetkin, “Story of secret diplomacy that ended Russia–Turkey jet crisis,” Hurriyet Daily News, August 9, 2016, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/opinion/murat-yetkin/story-of-secret-diplomacy-that-ended-russia-turkey-jet-crisis-102629

[4] Irina Slav, “EU ready to consider Iran joining Southern Gas Corridor,” Oilprice.com, February 19, 2019, https://oilprice.com/Latest-Energy-News/World-News/EU-Ready-To-Consider-Iran-Joining-Southern-Gas-Corridor.html

[5] Birgit Jennen and Arne Delfs, “With stakes rising, Merkel enters the fray to calm Turkey turmoil,” Bloomberg, August 16, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-15/merkel-enters-fray-to-calm-turkey-turmoil-as-german-stakes-rise

[6] “‘Pancake diplomacy’: Vladimir Putin, Xi Jingping flip pancakes at Russian economic forum,” The Straits Times, September 12, 2018, https://www.straitstimes.com/world/europe/pancake-diplomacy-vladimir-putin-xi-jinping-flip-pancakes-at-russian-economic-forum

[7] It was perhaps a telling coincidence that on the day Erdogan was hosting Putin and Rouhani in Ankara in April 2018, the prince was wrapping up his weeks-long, jam-packed US tour.

[8] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-12-12/saudi-arabia-plans-a-grouping-for-red-sea-gulf-of-aden-states

[9] Saudi Arabia had a similar transnational reach through jihadi networks, especially during the Soviet-Afghan war, but the Kingdom has put a curb on that alliance following the jihadis’ return home, where they held the Saudi leadership to the same standards as those they were preaching abroad. Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman, who reads the Saudi-jihadi partnership as a legacy of Iran’s 1979 revolution, seems determined to bring that story to a close.

[10] Although reports have linked the Houthi acquisition of missiles to Iranian support, the scale of such support is not comparable to the Saudi capacity for missile strikes in Yemen.

[11] “Sudanese as cheap mercenaries and scapegoat for the Emirati and Saudi defeats in Yemen,” iuvmpress.com, May 14, 2017, http://iuvmpress.com/9118. Similarly, the 2011 Saudi-led intervention in Bahrain to suppress anti-government uprisings there relied on a large number of Baloch mercenaries.