Cities and Networks Insights Series – A Note from the Editorial Team

In this article, Hyeju Jeong shows how state-planned industrialisation projects in East and West Asia, the expansion of US military complexes during the Cold War, and transnational entrepreneurial networks that operated largely independent of states converged to produce macro-scale exchanges between the two mega-industrial cities of Jubail in Saudi Arabia and Ulsan in South Korea. Through flows of capital, people and materials between the two nodes, Saudi Arabia and South Korea were able to build mutually dependent economic partnerships that supported the political leaderships of the two countries.

By Hyeju J. Jeong

Jubail, on the eastern coast of Saudi Arabia, conjures up extraordinary tales and memories in a seemingly unlikely place — South Korea. For Hyundai Corporation, one of the largest conglomerates in South Korea today, secured a contract in 1976 to participate in the transformation of the once small fishing and pearling town into an industrial mega-city. Hyundai was only one of the 10 main companies that participated in the Jubail project. The value of its contract, amounting to US$930 million, however, was staggering from the perspective of South Korea. It was equal to almost a third of South Korea’s national budget and 50 percent of its Gross National Product, at a time when the country was reeling from the impact of the OPEC oil embargo and a foreign reserves crunch. For Saudi Arabia, the making of Jubail was part of its Second Five-Year Plan (1975–1980) aimed at diversifying the economy. Prince Fahd, who was to become King later, served as the first chairman of the Royal Commission for Jubail and Yanbu. In the span of five years, Jubail was transformed through one of the world’s largest civil engineering projects and now hosts billions of dollars worth of refineries, petrochemical companies and steel plants.

ULSAN AND JUBAIL: HYUNDAI’S EMERGENCE AT HOME AND ABROAD

Lying beneath Hyundai’s operations in Jubail is a three-decades long history of the South Korean construction industry that developed in tandem with the military complexes that the United States established in South Korea and elsewhere during the Cold War. Hyundai Construction was one of several firms that rose to prominence in postcolonial Korea by undertaking projects contracted out by the US army. The building of US military bases requires massive infrastructural work since the bases are tantamount to self-contained autonomous cities comprising residential complexes, schools, medical facilities, groceries and other amenities within the camps that are under US jurisdiction. With the semi-permanent settlement of US troops on the Korean peninsula starting in 1945, Korean construction companies gained expertise, materials, steady contracts and business networks as subcontractors or joint-venture partners of American construction companies.[1] Hyundai’s founder, Chung Ju-young (1915–2001), who had previously worked various jobs at wharfs, a rice stall, and an automobile repair shop, had an exclusive channel of access to the US military bases: his younger brother, who had been working as an interpretation officer in the US military government in Korea.

Growing by piggybacking on US military bases in South Korea and later in Southeast Asia, Hyundai eventually built a massive shipyard and shipbuilding company in South Korea’s own mega-industrial city, Ulsan. Upon completion of the Ulsan shipyard, Hyundai supplied all the materials that it needed in the Jubail project from its subsidiary company in Ulsan, thereby taking its practice of intra-group transactions to a new international level. The internal supply chain between the two cities across the seas enabled Hyundai to maximise profits in both places and grow immensely as a conglomerate.

Ulsan is a historic deep-water port that had served as an important gateway for trade with Japan, China, Southeast Asia, Arabia and Persia from the 7th century onwards. In the late 1960s, it became a part of then President Park Chung-hee’s plans to build industrial bases on the southeastern coast of the peninsula, as far away from North Korea as possible. By 1973, Ulsan had become home to two entities that have significantly transformed its landscape and demographics: the largest shipyard in the world, and Hyundai Heavy Industries, which owns the shipyard.

Although Hyundai continued to grow domestically by building postwar infrastructural facilities across South Korea, critical for its expansion was its initial projects abroad, especially in wartime Vietnam, earnings from which were channeled into building the Ulsan shipyard. As the locus of the Cold War shifted westwards, in 1964, the South Korean government dispatched 300,000 troops to South Vietnam in response to a US request for military support. South Korean corporations followed suit, seizing business opportunities in the construction and military supplies sectors. Passing on contracting information privately to Korean firms were mostly American engineers and managers who had resided in Korea and relocated to Vietnam during the war. From its Vietnam War contracts, Hyundai amassed a total of US$178 million.

Profits from Vietnam provided 23 percent of the US$131 million required for the Ulsan shipyard construction project. The other 61 percent of the budget for Ulsan came in the form of foreign loans from different sources, which Hyundai secured through a circuitous network of brokers, banks and shipping company heads. Facilitating these loans was a US loan broker named Davis, who had resided in Korea in the 1950s and 1960s as a member of the USAID, the US agency for international development aid. Davis introduced Chung to the chief executive of an English shipbuilding company, who in turn introduced Chung to Barclays Bank as well as to a shipbroker, who then linked Chung with the Greek shipping giant George Stavros Livanos. Chung managed to convince Livanos to order two 260,000-ton ships although the Ulsan shipyard had not even been built yet. The advance payment from Livanos was used as a guarantee to secure Hyundai’s loan from Barclays Bank.[2] Ulsan shipyard was thus built through a series of interpersonal connections forged during the Cold War.

Figure 1. Present-day Hyundai Heavy Industries in Ulsan (Source: Korea Tourism Organization, http://english.visitkorea.or.kr/enu/ATR/SI_EN_3_1_1_1.jsp?cid=264557)

HYUNDAI’S PENETRATION INTO THE SAUDI MARKET

Around the time that Ulsan shipyard was completed with much domestic fanfare, South Korean construction companies rushed to secure contracts from the OPEC countries, which were then enjoying huge capital surpluses following the oil embargo. The decade that followed is often referred to in South Korea as the “Middle East Boom”. Notably, nearly 70 percent of all construction contracts in the Middle East during that period came from Saudi Arabia, South Korea’s main oil supplier. The number of Korean workers in the Kingdom began with about 3,000 in 1975, shot up to 16,812 within a year, and increased nine folds to about 100,000 people by 1982.[3]

Hyundai’s initial foray into the Middle East was in Iran and Bahrain in 1974. Soon afterwards, it landed projects in Saudi Arabia. Its entry point here, again, was through the US military. In 1975, Hyundai won a US$181.5 million contract to construct offshore facilities in Jubail for the US Army Corps Engineers (COE), which was assisting in the Saudi Naval Expansion Program (SNEP) under a security pact between the Kingdom and the US government. The next year, Hyundai received a US$361 million contract from COE for the expansion of the onshore mobilisation camp facilities at Jubail under SNEP.

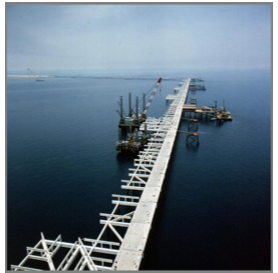

In between these two projects, Hyundai won the much bigger contract to build Jubail’s industrial harbour. Its task was to build an open-sea tanker terminal 12 km from the coastline where four oil supertankers could berth simultaneously. To maximise profits, Chung used Ulsan as a support base, ordering all materials needed for the construction to be supplied directly from Ulsan’s Hyundai Heavy Industries at the lowest possible cost and in the shortest possible time. This was done under the pretext of contributing to the South Korean economy.

The transfer of materials from Ulsan to Jubail is often narrated in South Korea with much drama. Among the key materials that Hyundai shipped from Ulsan were 89 “steel jackets”, which had to be driven into the seabed as a foundation for the pier. Each jacket, the size of ten-storey buildings and weighing 500 tons, was to be sealed at its ends to create huge air pockets, and led by a barge on the 12,000 km, 35-day long journey across the often stormy South China Sea and Indian Ocean. Chung even declined to have the shipments insured to cut costs. In the end, the shipment encountered only two minor accidents, and Hyundai was able to complete building the open-sea tanker terminal 10 months earlier than promised, enjoying a huge cost saving.

Figure 2. Hyundai Construction Site in Jubail Harbour (Date Unspecified). (Source: National Archives of Korea Online.)

Early completion of the Jubail project was also possible because Hyundai brought with it thousands of technicians, labourers and engineers from different parts of South Korea. South Korean workers were lured to the Middle East by wages that were double those they would have earned at home. By the time the building of Jubail Harbour was at its peak, Hyundai had almost 10,000 workers in Jubail, as well as in Bahrain and other places in the Gulf. The men signed one to three-year contracts and were not allowed to bring their families. Like other South Korean construction firms operating in the Middle East, Hyundai managed its workforce in a highly regimented manner.[4]

The Jubail project provided Hyundai with the pivotal springboard for it to expand exponentially, while allowing the South Korean government to overcome its foreign exchange crisis. Hyundai recorded an annual growth rate of 38 percent for the decade ending 1979. In the following decade, the company undertook new projects in places such as Kuwait, Abu Dhabi, and wartime Iraq.

From the perspective of the Saudi authorities and the main contractors, engaging Korean construction companies allowed them to break the monopoly that western companies enjoyed over major projects in the country and at significantly lower cost. For instance, there was a difference of US$300 million between the amount that Hyundai had bid for the Jubail project and that of the second lowest bidder. Also, South Korea provided a ready and well-disciplined labour force. The South Koreans were ideal partners for the Kingdom in other aspects as well. South Korea shared the Kingdom’s anti-communist ideology, while its distance from the Kingdom meant that it had little incentive to intervene in regional affairs. Furthermore, South Korean firms may have forestalled the potential discontent of the relatively marginalised middle-class merchants and bureaucrats in the Kingdom. These groups had little room to secure partnerships with western firms, which tended to team up with well-established Hijazi merchants or the royal family. Mid-sized South Korean firms in desperate need of the necessary partnership to undertake projects in Saudi Arabia linked up with the emerging Saudi middle-class businessmen and bureaucrats, providing the latter alternative channels of income through commissions, and often bribes.[5]

THE JUBAIL LEGACY

The days when South Korea exported its low-wage labourers to Saudi Arabia ended in the early 1980s. Yet, Jubail has continued to inform the transnational outreach of South Korean companies and the Saudi and South Korean governments. In 2015, Hyundai signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Saudi ARAMCO, the state-owned oil company, to jointly construct a shipyard in Ras Al-Khair, a port town about 60 km north of Jubail. The US$5 billion project will produce a shipyard close to the size of that in Ulsan by 2021. It was the grandson of Hyundai’s founder, now a senior executive vice-president of Hyundai Heavy Industries, who pushed for the project. Not surprisingly, he evoked the memory of Hyundai’s Jubail project 40 years ago at the MOU signing ceremony.[6]

Jubail may also have influenced the course of South Korea’s Middle East policies in the 21st century. Lee Myung-bak, the former president of South Korea (2007–2012), had become the youngest CEO of Hyundai Engineering and Construction in the middle of the Jubail Harbour project and made frequent trips to Saudi Arabia as well as Iraq. Lee’s experience in the Middle East at the time arguably shaped the direction of South Korea’s “resource diplomacy” towards the region when he was elected president of South Korea 30 years later.[7] Acting like a businessman, as he recollected in his memoirs, Lee sealed a deal in 2009 for the Korean Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO) to build nuclear plants in the UAE — but with a secret military pact. The deal has prompted South Korea to send an elite military unit to train UAE special forces in Abu Dhabi since 2011 and obliges the country to intervene militarily in the UAE in times of crisis and without the approval of South Korea’s National Assembly.[8] This is an unprecedented development in South Korea’s involvement in the Middle East.

South Korea’s trajectory towards the Middle East, which is predominantly commercial and politically low-key, has unfolded on the back of the infrastructure and business networks that initially grew out of the Cold War in Asia under the orbit of the US military presence. The mega-cities in South Korea and Saudi Arabia, which had been built through interdependent collaborations between firms and state-driven projects, remain as sites of industrial production and joint ventures between transnational corporations. South Korea’s direct military dispatch to the UAE, however, suggests that its engagements in the region that had been moulded by networks of transnational businesses are entering a new, unpredictable domain.

[1]Jeon Nag-geun and Kim Jae-jun, Peu-lo-jeg-teu Jung-sim Hae-oe-geon-seol-sa (Project-Based History of Construction Abroad) (Seoul: Gi-mun-dang, 2012), 13-52.

[2] Youngjin Choi and Jim Glassman, “A Geopolitical Economy of Heavy Industrialization and Second Tier City Growth in South Korea: Evidence from the ‘Four Core Plants Plan,’” Critical Sociology (April 2017): 1-16, 8-12.

[3] Moon Chungin, “Political Economy of Third World Biliteralism: The Saudi Arabian-South Korean Connection, 1973-1983,” (Ph.D dissertation, University of Maryland, 1984), 135.

[4] Grueling working conditions and the resulting tensions between managers and labourers backfired, erupting into three series of protests (1977–80) much to the alarm of the Saudi authorities, who banned Hyundai temporarily from further contracts in the Kingdom.

[5] Moon Chung In, “Korean Contractors in Saudi Arabia: Their Rise and Fall,” Middle East Journal 40, no. 4 (1986): 614-33.

[6] “Hyundai Heavy Industries and ARAMCO Sign MOU for New Business Opportunities Collaboration,” Hyundai Heavy Industries News, November 12, 2015.

[7] Shirzad Azad, “Déjà vu diplomacy: South Korea’s Middle East policy under Lee Myung-bak,” Contemporary Arab Affairs 6, No. 4 (2013): 552-566.

[8] June Park and Ali Ahmad, “Risky Business: South Korea’s Secret Military Deal with UAE,” The Diplomat, March 1, 2018.

About the author

Hyeju J. Jeong Hyeju J. Jeong is a Ph.D candidate at Duke University History Department. Her dissertation explores the the role of Mecca as the mediator and a critical hub for Chinese Muslim (Hui) networks of kinship and religion in the twentieth century that could periodically turn into channels of diplomacy. Her broad interests include historical anthropology, religious and diaspora networks between East and West Asia, and socio-cultural studies of the Arabian Peninsula through transnational approaches.