A discussion of key findings from STATA[1] analysis of Qatar University’s International Affairs surveys

By Charles Crabtree

Introduction and Methodology

The Rule of Law in Qatar Comparative Insights and Policy Strategies’ was a National Priority Research Program project funded by the Qatar National Research Fund from 2013-6 and focused on exploring, through surveys and interviews, stakeholders’ opinions on the meaning of the rule of law in the Arab Gulf, particularly in Qatar and Kuwait. 226 students at Qatar University’s College of Law were surveyed in 2014, with additional students surveyed at the Qatar Faculty of Islamic Studies, Kuwait University College of Law, and Qatar University’s International Affairs (QUIA) program. The following results are taken from 192 surveys conducted at QUIA in December 2015. First, second, and third year required classes were selected, out of which four classes were female and two classes male. This disparity reflects the reality that nearly twice as many students pursuing university education in Qatar are female.[2]

Examination of the quantitative data collected offers complicated and occasionally contradictory insights into students’ perceptions about the rule of law. Here, I focus on three: the relationship between shari’a and international legal principles as components of the rule of law; Qatar’s standing relative to its neighbors; and a broad glimpse of the social and legal institutions that serve as the foundation for the rule of law in Qatar.

Shari’a Principles

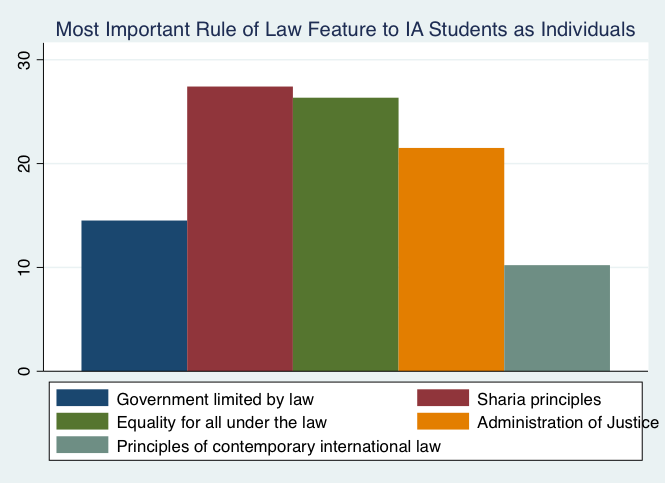

Shari’a principles were cited as the most important rule of law feature to QUIA students, narrowly edging out equality for all under the law and administration of justice.

Figure 1: Students’ individual perceptions of the Most Important rule of law features

The importance of shari’a amongst QUIA students was evident in other questions as well, although it was not always the dominant response. There was also some evidence that university education had a degree of influence on student priorities about features of the rule of law.

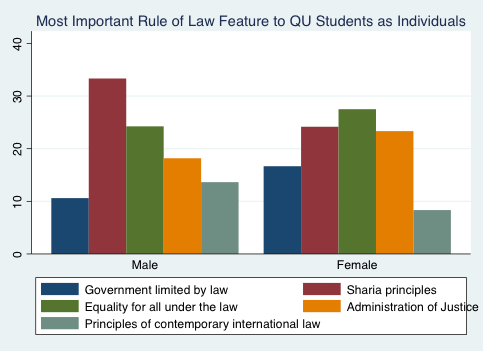

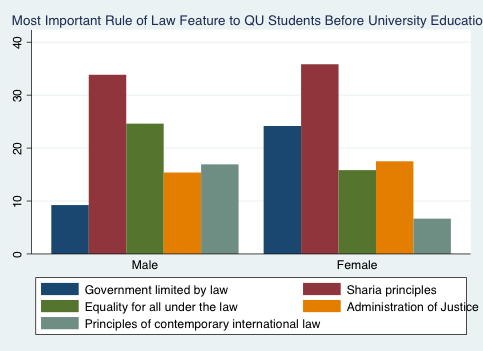

For example, when questioned about their opinion of the most important rule of law feature before attending university education, 35.14 percent of students responded that shari’a was the most important feature, compared to 27.42 percent after exposure to university education. This shift (7.72%) was especially apparent in female students’ attitudes toward shari’a. Before attending university, 35.83 percent of females felt that shari’a principles were the most important rule of law feature, compared to 24.17 percent in the present. Despite these changes in perception, both male and female respondents felt that shari’a’s influence on Qatar’s legal system was About the Right Amount.’

Figure 2: QU students’ individual perceptions of the Most Important rule of law feature, by Gender

Figure 3: QU students’ perception of the Most Important rule of law feature, by Gender

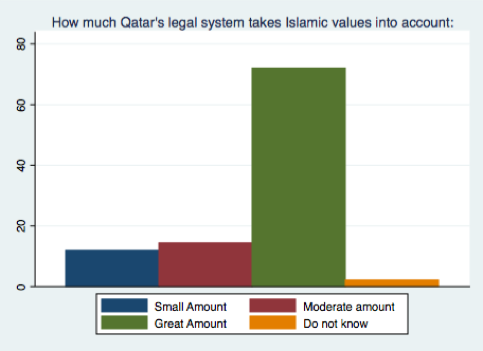

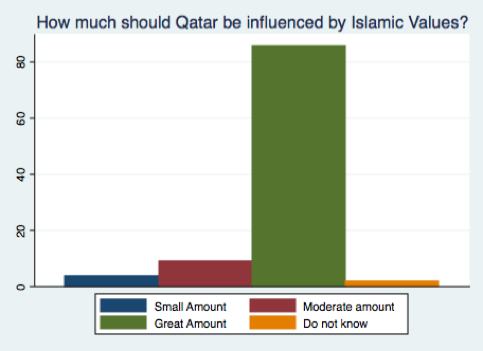

Respondents were also asked to measure shari’a’s influence on Qatar compared to other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Most respondents (38.3%) felt that shari’a had about the same influence on Qatar as it does in other GCC countries, although 35 percent felt that it had more influence. Approximately 72 percent of students felt that Qatar’s legal system took Islamic values into account a Great Amount.’

Figure 4: Respondent’s perception of the amount of influence Islamic values has on Qatar’s legal system.

Figure 5: Respondent’s perception of the amount of influence Islamic values should have on Qatar’s legal system.

The importance and influence of shari’a principles among survey respondents was undeniable. Shari’a was cited as the strongest or most important feature of the rule of law in every iteration of the question, and even when it was not the dominant selection by gender, it followed close behind the primary selection.

This strong consensus suggests that legal policy reform or development would need to take into account the centrality of shari’a to Qatari conceptions of the rule of law. It also raises questions about why shari’a plays such a dominant role in students’ perceptions of the legal system. One suggestion is that shari’a is largely inextricable from associations with legal order and notions of justice.[3] Indeed, students were quick to cite their belief that Qatar was an Islamic state when given the chance to elaborate further.

The relationship between legal education and shari’a is less clear. Third year students were less likely to cite shari’a as the strongest rule of law feature than first year students (17.86% to 30.85%, respectively). However, this disparity largely disappeared when students’ two highest rankings were considered. The impact of legal education on perceptions of the importance of shari’a might be explained by the past experiences with professorial staff or course offerings at QU. It might also suggest more complex considerations about what motivates students to pursue legal studies and their aspirations for what they might achieve with a degree. In either case, further questioning and analysis is necessary.

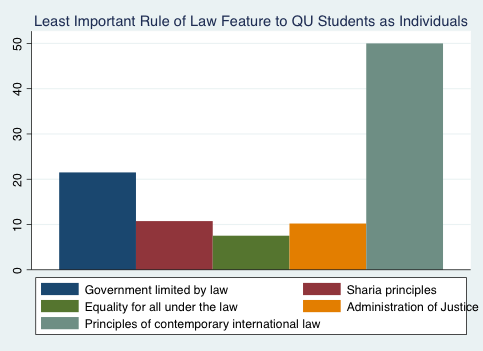

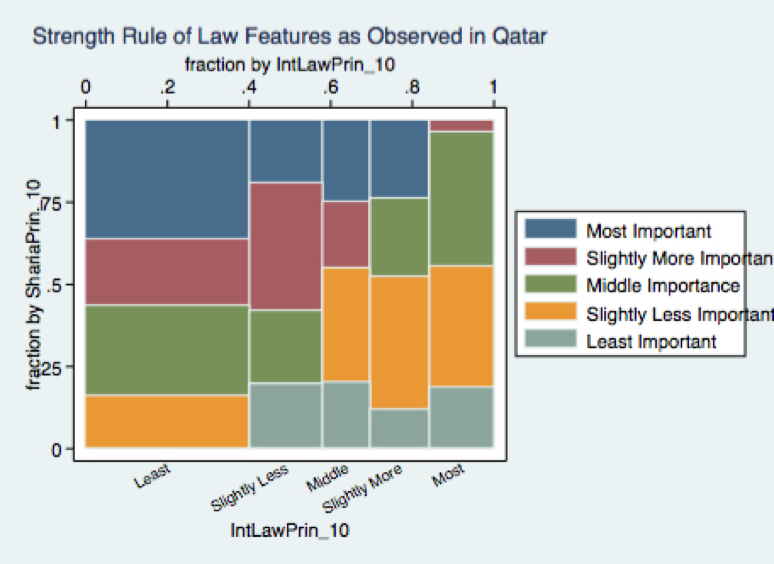

International Legal Principles

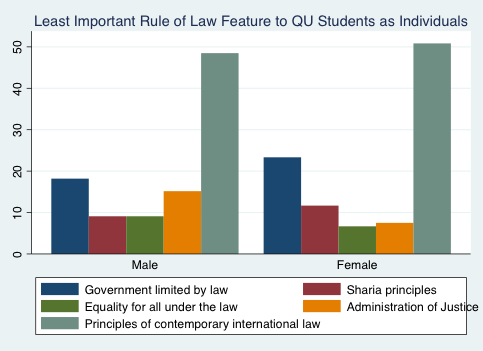

Students were also questioned about the current influence of international legal principles on the Qatari legal system and Qatar as a society. Just as there was consensus that shari’a was the most important and strongest feature of the rule of law, most students felt that international law principles were the weakest and least important features of both the Qatari legal system and Qatar as a society. Fifty percent of respondents also argued that international law principles were the least important rule of law feature to them at an individual level, a response that was virtually unchanged by exposure to university education.

Figure 6: Students’ individual perceptions of the Least Important rule of law features

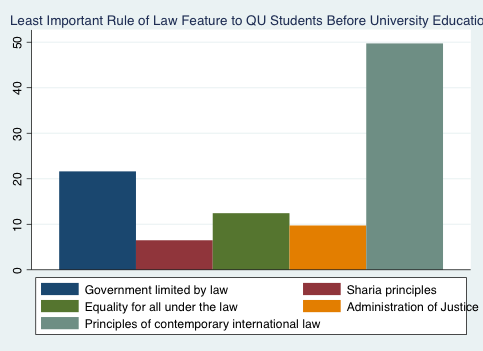

Figure 7: Students’ perception of the Least Important rule of law feature before university education

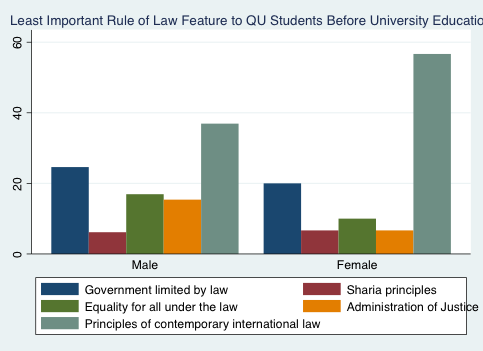

There was, however, some divergence of opinion between male and female respondents, as well as a marked shift in male respondents’ attitudes following exposure to university education. Before university education, 37 percent of male respondents cited international law principles as the least important principle of the rule of law compared to over 56 percent for females. When asked about the importance of the principles of international law as students, 48.5 percent of males cited it as the least important feature. This marks a 20% increase in males citing international law principles as the least important rule of law feature after exposure to university education.

Given that the data were not obtained by random sampling, this shift may not necessarily be significant. However, to the extent it is a real finding, several possible explanations come to mind. Because students are responding to their own recollection of how they felt about rule of law features before university education, it could be the case that they are simply reflecting that they now think less favorably of international legal principles than they once did. The disposition of faculty towards international law principles may also be a catalyst for this shift; however, this seems unlikely given the consistency of female students’ responses. It might also be the case that male students have gained a greater appreciation for a government limited by law, a response that rose in their estimation since beginning university studies, and have updated the order of their rankings at the expense of international law principles.

Figure 8: Students’ perception of the Least Important rule of law feature before university education, by Gender

Figure 9: Students’ individual perceptions of the Least Important rule of law feature, by Gender

How Qatar Compares to GCC Neighbors

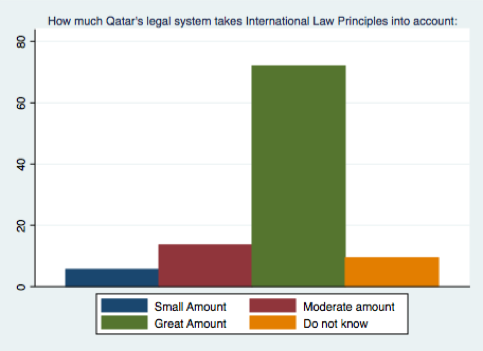

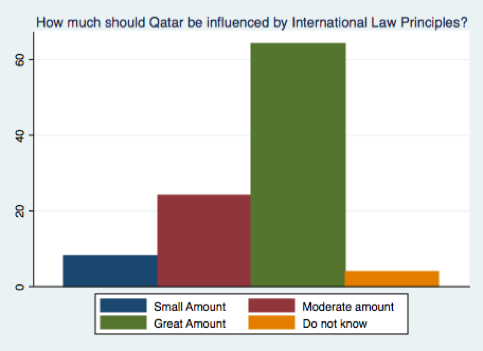

Although respondents overwhelmingly noted the strength and importance of international legal principles, most students felt that these principles had a greater or similar level of influence in Qatar compared to other GCC countries. Further, 72 percent of students felt that Qatar takes international legal principles into account a Great Amount,’ while 64 percent felt that a Great Amount’ of influence was appropriate.

Figure 10: Students’ perception of how much Qatar’s legal system takes International Law Principles into account

Figure 11: Students’ perception of how much Qatar should be influenced by International Law Principles

These responses suggest that the presence of international legal principles are acknowledged and accepted in Qatar, even as its relevance is perceived to be limited relative to other rule of law features available for selection. Responses to qualitative questions generally seemed to indicate an acceptance of some measure of input for international legal principles, albeit couched in an understanding of Qatar’s role as an Islamic state that greatly values its Islamic cultural traditions. One interpretation of these results is that students believe that international legal principles have been poorly implemented in Qatar. Under this view, perceptions of such principles – weak or unimportant – might be taken to mean that while there is space for international legal principles, existing efforts have failed or been underwhelming. Further questioning, combined with a deeper understanding of how surveyed students define international legal principles’ would be a crucial first step in clarifying this issue. Although that is beyond the scope of this analysis, our analysis of the qualitative data obtained in these surveys may offer greater clarity.

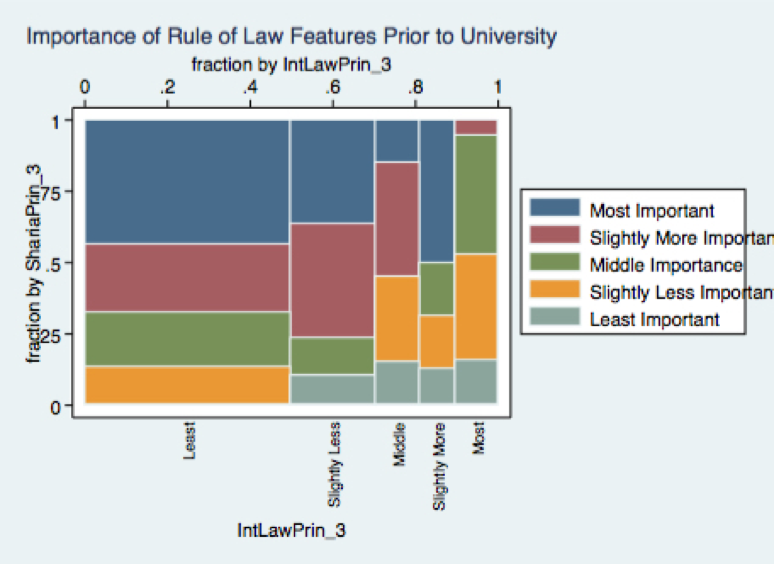

Relationship between Shari’a and International Legal Principles

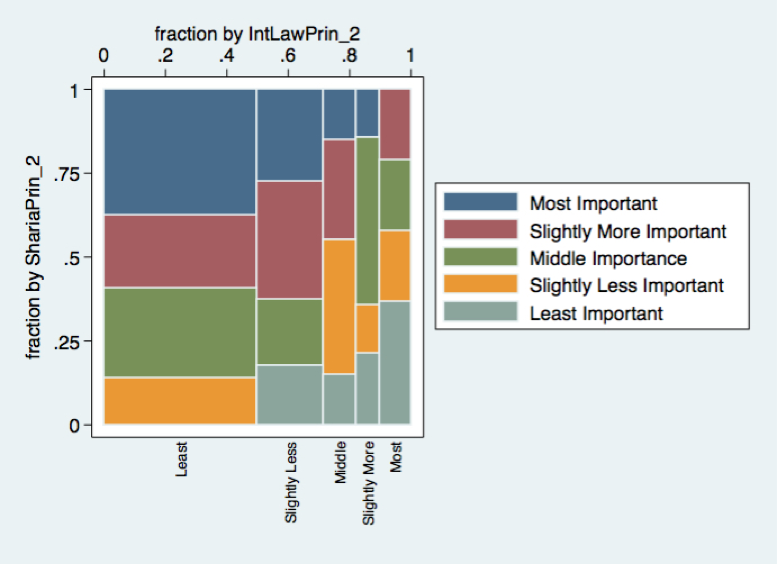

Further analysis of survey responses showed an obvious relationship between shari’a principles and international legal principles as features or influencers on the rule of law in Qatar. Students who believed shari’a principles to be the most important rule of law feature were much more likely to cite international legal principles as a weak or unimportant feature.

Figure12: Intersection of responses for the appropriate influence of shari’a and international legal principles

Figure 13: Intersection of responses for the importance of Shari’a and international legal principles before university education

Figure 14: Intersection of responses for the importance of international law principles and shari’a to Qatar as a society

Figure 15: Intersection of responses for the strength of international law principles and shari’a as rule of law features in Qatar

As the above spineplots demonstrate, QUIA students believe strongly in the importance of shari’a principles while demonstrating a high degree of skepticism about the strength or influence of international law principles. Almost 16 percent of students who cited shari’a principles as the most important rule of law feature to Qatar as a society also cited international legal principles as the least important rule of law feature, making it the most frequently selected combination, albeit tied with a combination of slightly more important/least important. Nearly half of students (47.48%) selected shari’a principles as most important or slightly more important while also citing international law principles as least important or slightly less important.

This distribution was typical across all four ranking questions. In each instance, the combination of shari’a as the most important feature with international legal principles as the least important feature was at least tied for the most common response. Based on these preliminary results, there is a strong indication that Qatar will need to carefully, if not necessarily equally, balance the influence of international and shari’a principles within its legal framework. Sustainable reform efforts will, in all likelihood, require input and discussion amongst diverse stakeholders, most notably from those in the legal, religious, and business sectors. The endorsement of key religious figures may be crucial in advancing any reform that expands the influence of international law.

Qatari Social and Legal Institutions and Influences: Strengths and Weaknesses

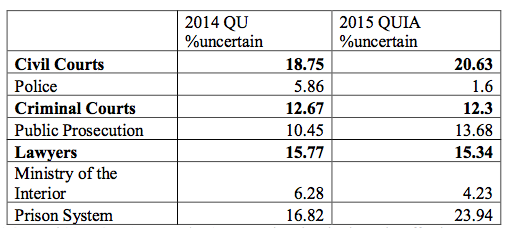

QUIA students had overwhelmingly positive views about the strength and effectiveness of the Qatari legal system in dealing with crime, civil and business disputes, and legal disputes between Qataris and non-Qataris. Students also indicated positive perceptions toward state legal and social institutions such as civil and criminal courts, police, university and legal education, and various traditional and online media sources. This finding, consistent with our other student data in Qatar and Kuwait, suggests that general legal problems in these GCC states may be relatively minor to a general local population, although seasoned legal experts and practitioners may identify problems within the legal system more specifically.

Interestingly, despite a high level of consensus, a comparatively large number of students were unsure about the effectiveness of some institutions. Over 20 percent of respondents were unsure about the effectiveness of prisons and civil courts, while over 15 percent were unsure of the effectiveness of lawyers. This lack of certainty about the effectiveness of some legal institutions might indicate a lack of direct exposure to the legal system. However, Qatar University law students, responding to the same survey in 2014, indicated similar levels of uncertainty about the effectiveness of Qatar’s civil courts and lawyers (See Table 1 below), and much higher levels of uncertainty the legal institutions’ ability to adjudicate disputes between Qataris and non-Qataris compared to QUIA respondents (16% to 6%, respectively). Students’ understanding and perceptions of the legal system and its institutions may be worth further analysis.

Table 1: 2014 QU and 2015 QUIA respondent’s uncertainty levels about the effectiveness state legal institutions

Conclusions: A Delicate Balancing Act

Shari’a principles stand out as the dominant feature of the rule of law, while international legal principles are relegated to a more minor role. Additionally, university education has a varying and inconsistent level of influence on students’ perceptions of the strongest and weakest rule of law features. Survey responses for QUIA students demonstrate a high level of consensus about the effectiveness of Qatar’s social and legal institutions, Qatar’s standing alongside its regional and global neighbors, and the role of rule of law features such as shari’a and international legal principles. As Qatar continues to develop its role as a regional and global power, an understanding of Qatari legal stakeholders’ perceptions of social and legal institutions and the meaning rule of law in Qatar, and how they change through the higher educational process, may prove significant to effective policy development and reform.

Charles Crabtree graduated with a Master’s in Public Policy and Administration from the University of Massachusetts-Amherst in May 2016. His research analyzed the relationship between human trafficking and illegal gold mining in sub-Saharan Africa and South America with particular focus on Ghana and Colombia. He currently works as an analyst for St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, TN and has previously worked for the International Trade Administration, the Memphis International Jazz Festival, and the Formation d’Anglais ├á Paris, in Paris, France. His research interests include the rule of law, political order, and the impact of transnational policy networks.

[1] STATA is a data and statistical analysis software program. It was used in the analysis of our survey findings and to generate the graphs featured in the article.

[2] Walker, L. (2014, June 12). Female university students in Qatar outnumber men 2:1 – Doha News. Retrieved July 29, 2016, from http://dohanews.co/female-university-students-outnumber-males-nearly/

[3] David M. Mednicoff, The Rule of Law and Arab Political Liberalization: Three Models for Change,’ Harvard Journal of Middle Eastern Politics and Policy (2012): 59