Rule of Law Series[1]

By Joanna E. Springer & Lubna Sharab

Introduction[2]

Qatar is gaining international recognition for leadership in rule of law reform, and participates increasingly in United Nations initiatives and global forums. However, Qatar has also been critiqued for divergences between its implementation of legal procedures and the demands of the international community, particularly in relation to the rights of migrant workers. Qatar’s international initiatives focus on other aspects of rule of law, particularly ‘law and order’ and control of corruption. Meanwhile, initiatives to develop a legal framework and institutional capacity to arbitrate transnational business agreements have moved full speed ahead, spearheaded by the Qatar International Court and Dispute Resolution Center (QICDRC). The perceptions of the Qatari population have remained an understudied aspect of Qatar’s engagement with international law and legal forums. Reform-minded actors must operate in a manner that takes account of both the country’s intense international interconnections and the larger population’s perceptions of rule of law.

The importance of understanding the attitudes of local citizenry vis-vis international legal norms, particularly related to human and political rights, has been increasingly emphasized by scholars and legal aid actors over the past decade.[3] International law, its advocates and institutions have been perceived by local citizenry in many Muslim countries as defined and governed by Western cultural, moral and religious (or ‘secular’) values.[4] However, broad Qatari perceptions of international law have not been discussed systematically until now. This Insight provides insights into the views of young, educated Qataris aiming to enter the legal profession regarding international law, and the challenges and opportunities it poses for Qatar.

The Qatar National Research Fund National Priorities Research Programme (NPRP), ‘Rule of law in Qatar and the Gulf Cooperation Countries (GCC)’ has carried out extensive research on perceptions of rule of law and international law among a variety of foreign and domestic legal actors. This Insight focuses on findings from an opinion survey carried out in March of 2014 with law students in Qatar University. The analysis counterposes perceptions and attitudes vis-vis two flashpoints of Qatar’s legal system and also its national identity; namely shari’a law, broadly defined, and international law, particularly international pressures and opportunities for visible global leadership. The qualitative survey results indicate that students are concerned about the appropriate implementation of shari’a law, which they view as central to the principles and practice of the Qatari legal system. Survey findings also reveal that students are concerned about the influence of international law on local traditions and national identity. While some students highlighted the impact of international law on shari’a law and Islamic practice, the issues of state sovereignty, and preserving national culture and local customs emerged strongly in the qualitative data. Meanwhile, a subset of students indicated that international law is important for Qatar’s development, while a minority also mentioned its importance for protecting the rights of citizens and workers.

Background on Qatari Engagement with International Law

The question posed by this Insight is whether local perceptions of ‘international law’ are generating a cautious and hesitant attitude vis-vis its influence on the country’s legal system. The analytical framework undergirding this exploratory research identifies two key concerns related to the influence of international law. First, the concern that international pressures vis-vis legal reforms and international agreements may interfere with Qatari sovereignty. Second, the concern that international legal actors aim to undermine tenets of shari’a law, perceived as indigenous to the Qatari legal system in contrast to Western-influenced international legal norms. The importance of this research question relates to the dual nature of the Qatari government’s discourse. One, outward facing, projects its leadership in the international legal arena as part of its own modernizing agenda, embodied in the Qatar 2020 vision. The second, inward facing, projects an image as guardian and guarantor of a rapid modernization that is identifiably Qatari, in terms of demographics, public mores, and even the look and feel of public spaces.[5]After winning the bid to host the Football World Cup in 2022, Qatar has come under intense scrutiny from the international human rights community, particularly due to investigative report findings by ‘The Guardian’ in 2014 of the human cost born by migrant workers building state of the art infrastructure for the World Cup. Harsh criticism dating back earlier from Human Rights Watch[6] and Amnesty International[7] amplified pressure on the Qatari government to introduce reforms in multiple domains of its legal system, ranging from political to social and economic rights.

However, perhaps not enough attention has been paid to the costs and benefits to legal reform faced by the Qatari government, particularly where domestic pressures are concerned. A 2013 NPRP workshop assessed the various challenges and institutional barriers faced by GCC governments when considering the ratification of international treaties and their implementation.[8] Not least among these is a gap in civil society advocacy on legal issues, and the fact that civil society actors are rarely included in decisions on international agreements or related reforms.

The fact that Qatari nationals only make up roughly 10 percent of the population[9] creates strong disincentives for granting rights to foreign workers, since doing so could lead to competition over resources and services now reserved for Qatari citizens. There are more than three times as many Indians and Nepalis alone as Qataris residing in the country.[10] Further, in parallel to its outward-facing leadership on international legal reform, the government of Qatar has intensified an inward-facing discourse emphasizing its role as protector of the national character and cultural heritage of Qatar.[11] Not least of its concerns is keeping demographics carefully in check, preventing migrant workers from entering carefully groomed public spaces, as well as enforcing moral standards on expatriate professional workers and tourists alike in public and commercial spaces.[12]

A conference on the protection of labor rights held in May 2014 convened high-level government officials, representatives of major Qatari firms, and representatives of international rights groups and the United Nations. Amnesty International was given the floor to express concerns and clarify the demands of the international community vis-vis migrant worker rights. This type of openness is remarkable among states in the Arab Gulf. However, the make-up of conference attendees is also symptomatic of the Qatari reaction to international pressure. While engagement is sustained at the ministerial level, representatives of Qatari society and civil society are not participating in these forums.

Research Methods

In mid-March 2014, the ‘Rule of law in Qatar and the GCC’ research team surveyed students from the women’s and men’s law colleges at Qatar University about their views on rule of law, shari’a and international law. Two hundred twenty-six mainly Qatari students[13] from eight classes (two from each of the four years of the law program) responded to the Arabic language questionnaire.[14] The survey instrument did not define international law and shari’a law in order to give students the opportunity to describe the terms in their own words. Responses to open-ended questions are represented in percentage terms to indicate their prevalence in the dataset.[15]

Findings of the Opinion Survey

Survey findings revealed that students had concerns about maintaining national identity and cultural values, including religious and traditional practices. However, these concerns were found alongside an awareness of the benefits to be gained by balancing domestic with international interests. On the one hand, students emphasized that Qatar’s sovereignty should be exerted to protect national identity. On the other hand, students understood that the road to development lies through the international community, and abiding by international agreements is a precondition for engagement in that community. However, responses clearly indicated that students expected to have a say in how those conditions are met.

Shari’a law in Qatar is applied in the domain of family law, similarly to several other Muslim-majority Arab countries. Student responses generally reflected this understanding of shari’a, and 13 percent of respondents specified that shari’a should be applied because of the country’s Muslim identity. However, 10 percent of students wanted the application of shari’a law through the penal code. Another handful indicated they believed that moral conduct should also be influenced by shari’a, for instance, by banning the consumption of alcohol or enforcing an Islamic dress code. Concerns about moral conduct indicated sensitivity regarding the behavior of tourists and expatriate white collar workers in Doha, revealing yet another cultural pressure resulting from Qatar’s rapid development. Some students also mentioned that shari’a should be applied in the domain of business and finance, a pertinent matter due to the prominence of foreign investment in Qatar.

Interestingly, students described international law mainly in negative terms, such as specifying what it should not interfere with, rather than using positive descriptions, such as explaining what its proper domain should be. It should be noted that 10 percent of students considered international matters one of Qatar’s greatest challenges, pointing specifically to ‘international pressures’ and international law.[16] These findings suggest that students perceive international law as deriving from outside Qatar, a source of pressure the country must deal with carefully and cautiously.

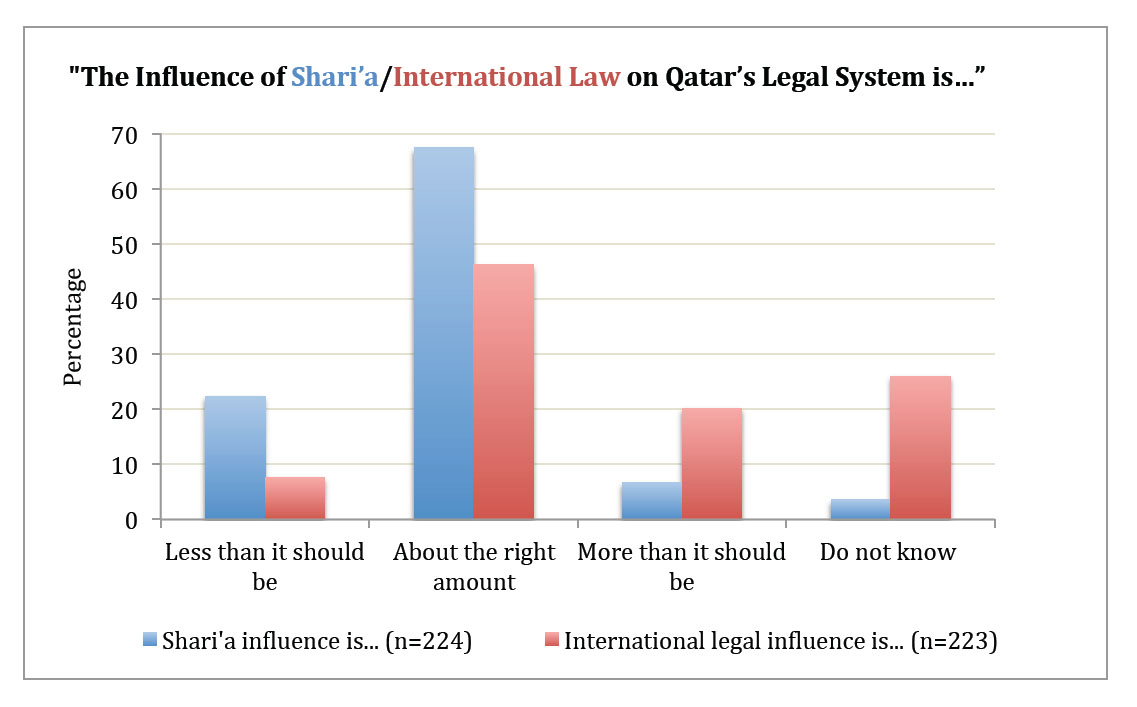

When respondents were asked to evaluate the current influence of shari’a and international law in the Qatari legal system, close to 70 percent approved the current degree of shari’a influence, versus 46 percent approving the influence of international law. (table below) More than 20 percent answered that shari’a should have more influence, while an equivalent percentage answered that international law should have less influence. These findings suggest young Qatari law students expect a significant role for shari’a in the legal system, in contrast to international law.

Several students specified that they were concerned about international law interfering with state sovereignty, while others worried about its impact on culture, traditions and Islamic practice. Some students specified that international law should not interfere with the domain of shari’a law. While more than 30 percent of students stated that shari’a should have a strong influence on the legal system, less than three percent indicated the same for international law. On the other hand, a small cluster of students thought shari’a should adapt to changes that come with modernity.

In general, survey participants perceive shari’a as reflective of their Qatari identity and culture, and appropriate to the Qatari legal context. In contrast, they felt the influence of international law should be carefully circumscribed and applied only in specified arenas. Interestingly, none of the students referred to international law as ‘secular.’ Further, the survey shows that students perceive an appropriate, albeit limited, role for international law in their legal system, specifically in the service of Qatar’s ongoing development. A subset of students specified domains that should be influenced by international law in relation to international agreements and international relations, with some mentioning migrant worker rights and human rights.

Conclusion

The findings of this study reveal that the reform-minded rhetoric of government institutions when they are dealing with international entities is not necessarily reflected in the attitudes of young Qatari students of law in Doha. While the government of Qatar has opened itself to outside scrutiny and convenes international forums on rule of law and legal reform, fealty to existing legal frameworks is still prevalent at the societal level. Overall, the students’ attitudes toward prevailing legal mores reflect an inward facing government discourse that makes legal and cultural traditionalism the gatekeepers of national identity. According to this rhetoric, as long as Islamic morals govern the public sphere, only the benefits of development will reach the Qatari nation, administered through a parallel legal framework tasked with managing foreign contracts and financial flows.

However, many of the students responding to this survey indicate they are savvy enough to understand the advantages as well as the disadvantages of increased influence from international legal forums. Improved awareness of international law among the new generation of Qatari lawyers, businesspersons and professionals could help the country navigate ongoing pressures and contradictions around transnational legal norms. Further, advocacy for migrant worker rights might well gain increased salience if situated in the moral framework of Islamic principles. In any case, a greater attempt to directly address the interests and concerns of Qatar’s citizenry will be needed to tip the balance in favor of meaningful legislation and implementation of pressing reforms.

Joanna Springer is a research and evaluation professional specializing in governance reform and community resilience programming. She has carried out research and supported grassroots organizations since 2009 in South Sudan, the West Bank, Qatar and the US. She is a Policy Analyst for Al-Shabaka: the Palestinian Policy Network. She holds a Master’s in Public Policy and Administration from the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.┬á

Lubna Sharab is currently a Master of Public Administration Candidate at Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs. She earned her BS in Foreign Service – International Politics. Lubna has worked for FIKRA Research and Policy as well as the Brookings Center Doha.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cah, Basak and Nazila Ghanea. ‘From Ratification to Implementation: UN Human Rights Treaties and the GCC.’ Workshop Series Report, University College London and University of Oxford, 2013.

Gardner, Andrew. ‘The Transforming Landscape of Doha: An Essay on Urbanism and Urbanization in Qatar.’ Jadaliyya. November 9, 2013. www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/15022/the-transforming-landscape-of-doha_an-essay-on-urb.

Kleinfeld, Rachel. Advancing the Rule of Law Abroad: Next Generation Reform. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment, 2012.

Mednicoff, David. ‘The Rule of Law and Arab Political Liberalization: Three Models for Change.’ Harvard Journal of Middle Eastern Politics and Policy (2012) : 55-83.

Mednicoff, David. ‘The Legal Regulation of Migrant Workers, Politics and Identity in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.’ In Migrant Workers and Arab Persian Gulf States, edited by Mehran Kamrava, 187-215. New York: Columbia and Hurst, 2012.

Mednicoff, David. ‘National Security and the Legal Status of Migrant Workers: Dispatches from the Arab Gulf.’ Western New England Law Review 33, no. 121 (2011): 121-162.

[1] All the contributions to this Insight are inspired by, and many of the individual authors supported by, ┬áQatar National Research Fund’s National Priorities Research Program Grant 6-459-5ÔÇô050, the Rule of Law in Qatar and the Arab Gulf Project. We acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Noha Aboueldahab, Sarah Kofke-Egger, Susan Newton, Gwenn Okruhlik, Lubna Sharab, Sylvain Taouti and RA’s at Qatar University and the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

[2] Special thanks to Dr. David Mednicoff and Dr. Nele Lenze for editorial suggestions and guidance.

[3] See for instance, Rachel Kleinfeld, Advancing the Rule of Law Abroad: Next Generation Reform (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment, 2012), 90-94. The results-oriented ‘second generation law reform’ she describes is focused on engaging local actors and structures, both formal and informal, at multiple levels.

[4] See for instance, David Mednicoff, ‘The Rule of Law and Arab Political Liberalization: Three Models for Change,’ Harvard Journal of Middle Eastern Politics and Policy (2012) : 55-83.

[5] Andrew Gardner, ‘The Transforming Landscape of Doha: An Essay on Urbanism and Urbanization in Qatar,’ Jadaliyya, November 9, 2013, www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/15022/the-transforming-landscape-of-doha_an-essay-on-urb.

[6] A letter from Human Rights Watch on Qatar’s candidacy for membership in in the UN Human Rights Council, October 15, 2014: http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/10/15/letter-hrh-shaikh-tamim-bin-hamad-al-thani-candidacy-human-rights-council.

[7] Amnesty International’s 2015/2016 report on Qatar features migrant workers’ rights: https://www.amnesty.org/en/countries/middle-east-and-north-africa/qatar/report-qatar/.

[8] Basak Cah and Nazila Ghanea, ‘From Ratification to Implementation: UN Human Rights Treaties and the GCC’ (Workshop Series Report, University College London and University of Oxford, 2013).

[9] Qatar profile in World Report 2016 from Human Rights Watch: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2016/country-chapters/qatar.

[10] Statistics published by Jure Snoj on bqdoha.com, December 18, 2013: http://www.bqdoha.com/2013/12/population-qatar.

[11] David Mednicoff, ‘The Legal Regulation of Migrant Workers, Politics and Identity in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates,’ in Migrant Workers and Arab Persian Gulf States, ed. Mehran Kamrava (New York: Columbia and Hurst, 2012), 187-215.

[12] David Mednicoff, ‘National Security and the Legal Status of Migrant Workers: Dispatches from the Arab Gulf,’ Western New England Law Review 33, no. 121 (2011) : 121-162.

[13] Nearly 74 percent (n=167) of the students identified as Qatari, about 10 percent (n=22) identified as a nationality other than Qatari, and a little over 16 percent (n=37) did not identify.

[14] The sample was slightly skewed in favor of female respondents (a ratio of male to female of 0.6 to 1), due to class attendance on the days the survey was administered. Although not representative, the sample is sizeable given the total student body of the school of law was 800 in that year.

[15] For qualitative data, the percent of students is calculated out of the entire sample of 226, even if the response rate to a particular question was low. This is to avoid confusion due to the open-ended design of these questions preventing simple aggregation of varied responses.

[16] The response rate to a question on the appropriate influence of international law was significantly lower than for the same question regarding shari’a law (54 percent compared to 80 percent), with eighteen students responding ‘I do not know’ about international law, suggesting that students are significantly less familiar with international law than they are with shari’a law. However, understandings of the proper domain for shari’a law vary significantly more than those regarding international law.