By Serkan Yolacan

A bribery scandal that swept Turkey at the end of 2013 brought the world’s attention to a curious phenomenon. At the height of Western sanctions against Iran, a secret financial corridor apparently carried billions of dollars in gold from Turkey to Iran in return for Iranian natural gas. The operation was simple: Payments made in Turkish lira to purchase Iranian gas were transferred to the Turkish state-owned Halk Bank. Iranians used these funds to buy gold in Turkey, which was then carried in suitcases to Dubai, where it was sold for foreign currency. This ‘gold-for-gas’ trade at once helped balance Turkey’s growing trade deficit and shored up Iran’s dwindling foreign exchange reserves in the shadow of international law.[1]

Though the illicit trade involved top ministers in both countries, at the center of it all was a middleman named R─za Sarraf (or Reza Zarrab in Iran), a Turkey-based Iranian Azerbaijani with dual citizenship in both Turkey and Iran.[2] A businessman in his early thirties, Sarraf came from a wealthy family in the Iranian city of Tabriz. After doing business in Dubai, Sarraf moved to Istanbul, where he established a gold company. Orchestrating his business and family connections within Iran and Turkey, Sarraf plugged himself into the political elite in both countries, including the former Iranian president, Mahmoud Ahmedinejad, and the former head of Iran’s Social Security Organization, Saeed Murtazavi. While in Turkey, he established personal connections to Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and a number of his ministers. Thanks to these ties, Sarraf facilitated the transfer of some 200 tons of gold, worth $12 billion, from Turkey to Iran via Dubai.[3] His name betrayed his m®tier: Sarraf in Turkish is a borrowed Arabic word for moneychanger or dealer in precious metals, especially gold.

In November 2015, only two years later, another incident made international headlines: a Russian jet was shot down by Turkish forces over the Turkish-Syrian border. The news fell like a bomb on the so-called suitcase traders shuttling between Moscow and Istanbul. More was at stake than just unregulated trade, however; Turkish construction firms in Russia and Russian tourists in Turkey had bound the two economies together, along with Russian natural gas and Turkish agricultural products flowing in opposite directions.[4] The incident put much of this traffic at risk and caused a media frenzy in both countries. At the peak of the Turkish-Russian crisis, a professor in Ankara named To─ƒrul ─smay─l received several phone calls from Russian media inviting him to convey the Turkish view to the Russian public. A former Soviet citizen from the Kmir region of Azerbaijan, ─smay─l’s familiarity with Russia went back to his student years at the Lomonosov Moscow State University, where he completed his doctoral degree in history. His educational path would later take him to Baku on the Caspian and finally to Istanbul University. Now a Turkish citizen with fluency in Russian, a qualification hard to come by among Turkish academics, ─smay─l was indeed the perfect candidate. Soon he was in NTV’s Moscow studio, where he responded to his Russian peers’ provocative questions in a primetime live debate. Back home in Ankara, ─smay─l continued to receive invitations, this time from Turkish media, who sought him to convey the Russian perspective to the Turkish public.

Individuals like Sarraf and ─smay─l are examples of a classic figure in the anthropological literature, namely, the broker.[5] Their brokerage, however, is no small affair. If Sarraf the gold trader became the liaison between two states, ─smay─l the scholar played the messenger between two nations. Their role is akin to that of a diplomat, though officially they bear no such title. It is not diplomatic immunity across borders but cultural immersion within them that underpins these cases of international brokerage. In each case, we have an individual who is culturally conversant with multiple political domains. Sarraf feels at home in Istanbul just as he does in Tehran. Similarly, ─smay─l’s deep familarity with Turkey and Russia puts him equally at home in Moscow and in Ankara.

Order Beyond Borders

What should we make of this ability to localize in multiple political domains at once? Are Sarraf and ─smay─l exceptional cases, where two entrepreneurial individuals punch in and out of otherwise disconnected social orders? Or do they provide a glimpse of a phenomenon that is socially much thicker? If indeed Sarraf and ─smay─l move along socially crowded routes, then on the same routes we must expect to see states interacting with one another beyond the constraints of the formal interstate system. Evidently, the social basis of such interaction is not to be found in one political domain but in many, spread out through networks of business, kinship, religion, education, and labor. How then can we analyze a social order that is constitutive of multiple political domains?

Addressing these questions requires an expansive vantage point, which is difficult to procure from within a single political domain. An alternative viewpoint emerges, however, if we follow our two characters back to their homeland in Transcaucasia, a three-way land bridge connecting Russia (north), Iran (east), and Turkey/Byzantium/Europe (west).[6] Historically, Transcaucasian territory changed hands among empires from these three directions. And from Transcaucasia, Azerbaijanis spread north to Russia and east and west to Iran and Turkey as a diasporic people. Although the competing nationalims of the short twntieth century has divided their diasporic horizons, they have been reconnecting since the Cold War’s end. Today, as Azerbaijanis move between different corners of their old diasporic space, their passages and transactions constitute a social web across Iran, Turkey, Russia, and post-Soviet Azerbaijan. When seen from within a single state, this transnational web appears lopsided. Placing Azerbaijanis at its center, however, offers a different perspective: an expansive social basis that is shared by multiple political domains.

A network-centric diasporic perspective shifts our attention from individual states to their shared frontiers as the loci of informal diplomacy. In frontier spaces, states connect through a shared social tissue interwoven by old diasporas. Azerbaijanis are one of them, whose diasporic history reveals durable vectors of exchange and mobility across political boundaries. This temporally capacious, transregional perspective enables us to examine Iran, Turkey, and Russia as part of a single, interconnected political landscape held together by ties of family, trade, religion, and shared past. Calling this region West Asia opens up the closed box of the Middle East through the bridge of Transcaucasia and its erstwhile Azerbaijani Diaspora. The rest of this paper follows Azerbaijanis across old frontiers and analyzes the consequences of such movement for the states around them.

Turko-Persian Frontier

Sarraf’s Tehran ‘Dubai’ Istanbul route is busy today with thousands of Iranians who travel to Turkey and the United Arab Emirates for business and leisure. Without any American representation in their country, Iranians file their visa applications either at the U.S. Embassy in Ankara or at the consulate in Dubai. They are not bothered with such formality when entering Turkey, however, thanks to the visa-free travel agreement between the two countries. Many of these Iranians who head in and out of Turkey every year have origins in the city of Tabriz or its environs. These are the Iranian Azerbaijanis, whose ethno-linguistic ties to Anatolian Turks enable them to localize in Turkey with relative ease. Sarraf is one of them.

Azerbaijanis’ roots within Iran stretch back a millennium, when Turkic migrations from Central Asia resulted in a plethora of Turkic-speaking communities across Iran and beyond. In the region of Azerbaijan, centuries of Turko-Persian interpenetration produced a Turkic-speaking people acculturated in Persian customs, Tabriz being their entryway to the Iranian realm. Today, one rarely hears Persian on the streets of Tabriz, but the ease with which Tabrizis juxtapose Persian phrases and idioms within their Turkish vernacular speaks volumes about the Azerbaijanis’ hybrid roots. Such hybridization manifests itself most visibly in the historical persona of Shah Ismail, the founder of Iran’s Safavid Dynasty, who had origins in Azerbaijan. Ismail was an Iranian king who wrote most of his poetry in Turkish, yet at the same time, this Turkic poet would associate himself with the classic heroes of Persian mythology.

This type of cultural conversance epitomized by Shah Ismail has played out in a range of diplomatic episodes in Ottoman’Iranian relations, starting with the belligerent letters exchanged between Shah Ismail and Sultan Selim prior to the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514. While the Ottoman sultan preferred the prestigious language of his court and wrote his letters in Persian, the Iranian shah would reply in Turkish, the language of his army and his poetry. Centuries later, when the first Ottoman ambassador was sent to Qajar Iran in 1811, the interpreters who accompanied the envoy to Tehran were later sent back to Istanbul for the ‘Iranians’ good command of Turkish’ rendered their services redundant.[7] Even the leaders did not need an interpreter at times, as was the case with Iran’s Reza Shah and Mustafa Kemal Ataturk when the two met during the shah’s visit to the Turkish capital in 1934. During their meeting, the two spoke in Turkish, Ataturk in the Istanbul dialect and Reza Shah in the dialect of Tabriz, the hometown of both his mother and his wife.

Azerbaijanis’ cultural conversance with both countries came into full view at the turn of the past century, when the nearly simultaneous constitutional revolutions shook Russia (1905), Iran (1906), and the Ottoman Empire (1908). A significant portion of Iranian diplomats and dissidents in Istanbul were Iranian Azerbaijanis, who had established diasporic pockets of trading communities stretched across Anatolia, linking the Ottoman capital to the Iranian city of Tabriz. These trade routes extended to the cities of Tbilisi and Baku in the Russian Caucasus, where Iranian Azerbaijanis mingled with their kin who were Russian subjects. As Iranian dissidents in exile, embedded in the mercantile networks centered in Tabriz, Azerbaijanis infused the economic grievances in Iran with notions of patriotism and constitutionalist demands developed in conversation with Russian, Ottoman, and Armenian constitutionalists. Azerbaijanis’ local cosmopolitan ties across three empires propelled the constitutional revolution in Iran (1906’1911).

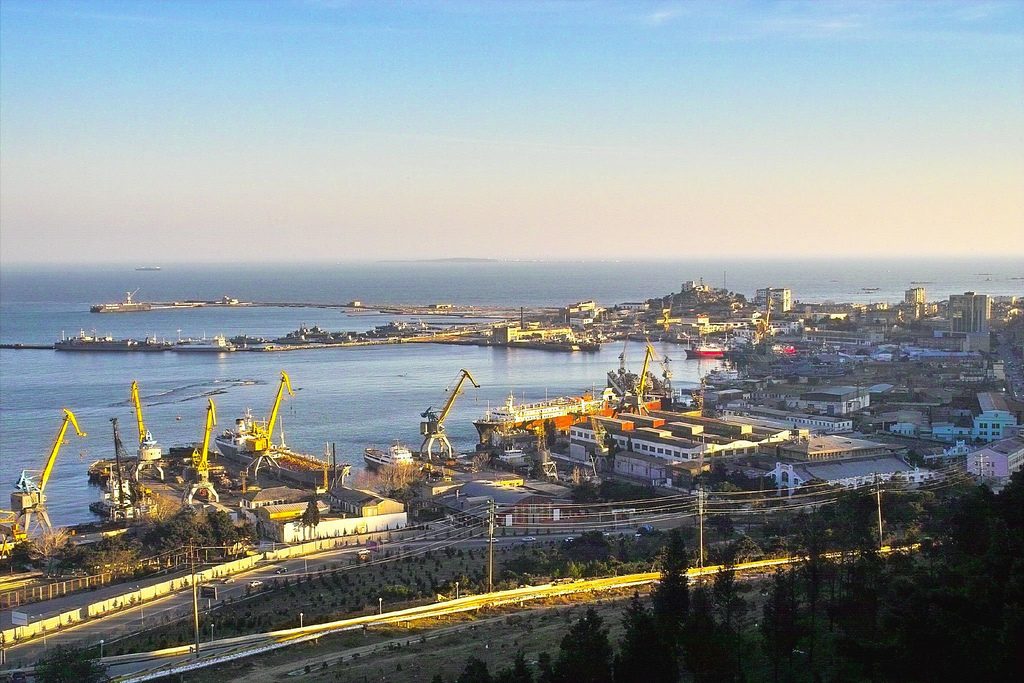

Russo-Persian Frontier

Although Azerbaijanis’ diasporic horizons were divided by the competing nationalisms of the twentieth century, they have been reconnecting since the Cold War’s end. Today, thousands of Shi’a Azerbaijanis from both Turkey and the former Soviet space go to Iran every year to visit the shrines of Imam Reza in Mashhad and Fatima Masumeh in Qom. Hundreds of Azerbaijani youth study there in the Shi’a seminaries. This movement in and out of Iran, where an estimated twenty million Azerbaijanis live as local nationals, extends the Shi’a networks to places like Baku, Istanbul, and Moscow, where Azerbaijanis have a significant presence. Iranian Azerbaijani clerics move in the other direction, especially into Transcaucasia, becoming Iran’s cultural diplomats in post-Soviet Azerbaijan, where the Soviet collapse had thrusted millions of nominal Shi’as into the open.

Although these Iranian clerics-cum-diplomats were later banned from post-Soviet Azerbaijan as a result of American pressure after 9/11, Soviet Azerbaijanis who followed their brethren back to Iran have kept the cross-border communication alive and even extended it to far-flung corners of Russia through family ties.[8] Every year during the months of Muharram and Ramadan, Iran-educated Azerbaijani mullahs travel to various Russian cities, where they are immersed in conversations with eager audiences made up of mainly Azerbaijanis and smaller numbers of other Shi’ites from places like Tajikistan, Pakistan, and Lebanon. Such mixed crowds gather in private homes or Hussainiyahs (congregation halls for Shi’a commemoration ceremonies) established by diasporic pockets of Azerbaijani communities distributed over the eleven time zones of the former Soviet Union.

Pious Azerbaijani merchants sustain these connections by sponsoring their Iran-educated kinsmen during their stay in Russia. Today, over one million Azerbaijanis live in Moscow alone, mostly working in the bazaars as petty traders but also as import’export merchants. Their family ties and remittances to Transcaucasia constitute a socio-economic corridor between Moscow and Baku, giving the Kremlin a strong say in the internal affairs of post-Soviet Azerbaijan. Along the same corridor, the Iran-educated Azerbaijani clerics extend this north’south axis into Iran. The Kremlin is hardly bothered by this movement, seeing Shi’a Islam as less of a threat than’even an antidote to’the Sunni Islam sponsored by the Turks and the Gulf. Thanks to this accommodation, Iran’s Shi’a revivalism reaches northward toward the Baltic while Russia receives a warm welcome in the Caspian, where its missiles are launched to hit targets in Syria.

This is not the first time Azerbaijanis became the Kremlin’s entryway into the Persian domain. Azerbaijanis from both sides of the Iran’Soviet border played key roles in the Soviet-led Comintern activities within Iran during the interwar period.[9] During the Second World War, when the Soviets occupied northwest Iran, Stalin mobilized Soviet Azerbaijani cadres from Baku to offer their kinsmen in Tabriz an alternative future of socialist nationalism. When the Soviet occupation culminated in a puppet state in northwest Iran, the state was led by Ja’far Pishevari, an Iranian Azerbaijani who had a history with the Soviet Comintern and family on both sides of the border (His brother was a captain of medical service in the Red Army.)[10] Today, Azerbaijanis are moving along the same corridor as merchants, mullahs, scholars, and students, weaving an expansive social web across the former Russo-Persian frontier. States move toward or away from one another along the same web to build transnational influence over societies beyond their domains.

Turko-Russian Frontier

Just as Iran’s Shi’a revivalism and Russian Eurasianism are intertwined across the former Russo-Persian frontier, Turkish regionalism is entangled in the same web on the east’west axis. In the wake of the Soviet collapse, Turkey-based Sunni Muslim networks highlighted their ethno-linguistic ties to post-Soviet republics in Transcaucasia and Central Asia. They also infused those ties with a Sunni bond by invoking the millennial past of Naqshbandi Sufism, whose historical expansion is intertwined with Turkic migrations from Central Asia into Iran, the Caucasus, and Anatolia. The invocation of this deep past projects a contiguous historical landscape that precedes the institutionalization of Shi’ism in Iran as well as the Russian expansion into inner Asia. In a bid to reinvigorate this historical geography, Sunni Muslim activists spread to the former Soviet space, where they opened schools, businesses, and charities. Turkish leadership played an active role in this process by politically sponsoring these cross-border enterprises and opening Turkey to their clients and students. Through this state-sponsored network, thousands of Azerbaijanis from Transcaucasia have entered Turkey, where they pursue careers today in a variety of professions while maintaining family ties in Russia, Iran, and Azerbaijan.

It is worth noting that this Turkish-Azerbaijani network was, in terms of political Islam, a Sunni-Islamist ally of the United States, paralleling the Sunni’Islamist’U.S. alliance from the Gulf that went into Soviet Afghanistan in the 1980s. Emboldened by this regional-global collaboration, Turkish Sunni communities extended their networks of education, business, and philanthropy to other regions. Flag followed trade and network in this case; Turkish embassies and airlines expanded in their wake, underwriting Turkish transregionalism in the 2000s. In other words, the social infrastructure of what has been dubbed ‘neo-Ottomanism’ was first laid down and extended across the crumbling Soviet space by the Turkish-Azerbaijani diasporic networks.

This Turkish-Azerbaijani network also builds on the memory of earlier encounters across the Turko-Russian frontier, particularly that of the pan-Turkist networks at the turn of the past century. As the Tsar’s Muslim subjects, Azerbaijanis (together with Tatars) developed pan-Turkic ideas in Russia and later carried that pan-Turkism into the Ottoman center, where it exploded in the Great War’s wake, becoming an asset to the Ottomans and a liability to the Bolsheviks. Although pan-Turkism lost ground when the Bolsheviks and the new Turkish government signed treaties of non-interference, the potency of old dreams was not lost on those who wanted to undo those borders. Hitler was one of them, who had to suspend his racial theories to use Pan-Turkism as a strategic manoeuvre to harness support from the Soviet Union’s Turkic populations. With their army sunk deep in the Russian plains, Nazi leadership sought the collaboration of exiled pan-Turkists such as Mammad Amin Resulzadeh, who was once Stalin’s socialist comrade in Russian Baku and later a fervent constitutionalist in Iran before he became a pan-Turkist in the Ottoman capital.

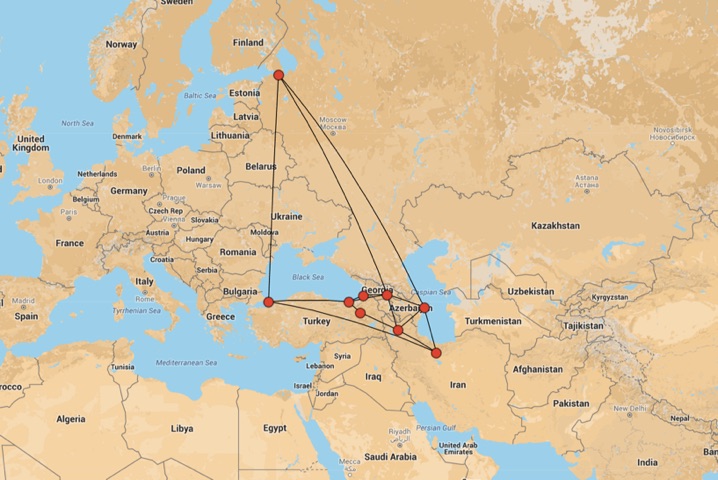

Map 1: Azerbaijani Triangle with Tabriz, Tbilisi, and Baku at its vertices.

Map 2: Azerbaijani Triangle with Tehran, St. Petersburg, and Istanbul at its vertices.

Conclusion: The Azerbaijani Triangle

Sarraf and ─smay─l’s routes are not only socially crowded, but also historically deep. The view from their homeland, Transcaucasia, reveals historically patterned vectors of exchange and mobility, which have tied together the political fate of Turks, Iranians, and Russians. This common fate, though invisible within each domain, comes into full view from the diasporic perspective of Azerbaijanis, whose routes crisscross all three domains.

Today, the many routes on this expansive social map overlap in Baku, where a typical Azerbaijani family would have members going in and out of all three domains: an uncle doing business in Russia, a cousin studying in Turkey, or a sister visiting the shrine of Imam Reza in Iran. As the accounts of their dwelling and traveling accumulate within the same family, they form a shared repertoire of pasts and places, which can be explored by any member as a potential route into the future. These diasporic Azerbaijanis can move across political landscapes by variously holding and dropping the many strands of their own diasporic history. Each political domain retains a different subset of these strands, but diasporic Azerbaijanis have the full set, and Baku is where they converge. Seen from there, the old imperial centers of Tehran, St. Petersburg, and Istanbul appear as alternative vertices of the same triangle.

The view from the edge may reveal similar triangles and other geographical shapes across West Asia, like that of the Armenians in the past or the Kurds today, who are moving in and out of Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria by mobilizing ties of kinship, business, political camaraderie, and shared past. Following their tracks sheds new light on post’Cold War Muslim transnationalism. Whereas state-centric analyses have pointed to increasing fragmentation through sectarian competition across West Asia, a network-centric view lays bare cross-sectarian entanglements informed by the local cosmopolitanism of old diasporas. By becoming an insider and an outsider of different political domains, diasporic individuals can move between seemingly entrenched sectarian divisions and political loyalties. Their passages and transactions allow the states around them to interact with one another beyond the modus operandi of the formal interstate system. Such a view enables us to harness data, concepts, and insights from the past to inform contemporary crises, such as that of Syria today, in which regional powers entangle in ways that befuddle conventional state-centric and international relations analyses.

Serkan Yolacan is a Research Associate at MEI and a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Cultural Anthropology at Duke University. His research focuses on the role of diasporas in the transformation of state and society. His dissertation project, entitled The Azerbaijani Triangle: Order Beyond Borders Across West Asia, employs diasporic analytics to explore transnational networks of religion, education, and business across Iran, Azerbaijan, Russia, and Turkey. He is a graduate of Sabanci University, Central European University, and Duke University and has previously worked as Projects Officer at the Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation in Istanbul.

[1] Jonathan Schanzer, How Iran Benefits from an Illicit Gold Trade with Turkey. The Atlantic. May 17, 2013. http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/05/how-iran-benefits-from-an-illicit-gold-trade-with-turkey/275948/

[2]. Patricia Hurtado, Gold Trader at Heart of Turkey Graft Scandal Charged in U.S. Bloomberg. The Atlantic. March 22, 2016. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-03-22/gold-trader-charged-in-u-s-with-violating-iran-sanctions

[3]. Mehul Srivastava and Isobel Finkel, Turkey Sells 200 Tons of Secret Gold to Iran. Bloomberg. June 26, 2014. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-06-25/turkey-sells-200-tons-of-secret-gold-to-iran

[4]. Joshua Chaffin and Mehul Srivastava, Moscow’s Flight Ban Hits Turkish Tourism Industry. The Financial Times. December 17, 2015. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/6146d0e6-9f5b-11e5-beba-5e33e2b79e46.html#axzz441fKfQyg

[5]. For classic anthropological accounts on the subject, see Clifford Geerts, Javanese Kijaji: The Changing Role of a Cultural Broker (Comparative Studies in Society and History 2006 2[2], 228’249), and Philip Carl Salzman, Tribal Chiefs as Middlemen: The Politics of Encapsulation in the Middle East (Anthropological Quarterly 1974 47[2], 203’210). For a review of the theme of brokers and brokerage within the anthropological literature, see Johan Lindquist, Brokers and Brokerage, Anthropology of, in International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Science, 2nd edition (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2015). Although the broker figure has retreated from anthropology, it has enjoyed a new lease on life in the recent studies in transnational history. If tribal chiefs, traditional healers, and local Muslim leaders were the classic ethnographic exemplars of brokers in the anthropological literature, brokers in the recent historical scholarship brought attention to a wider range of figures, including traders, artists, scholars, holy men, mercenaries, and such. The analytical potential of the term is laid bare in a range of historical contexts from the fluid maritime world of the early modern Mediterranean to the Cold War diplomacy across diligently guarded borders of the twentieth century. For an example of the former, see E. Natalie Rothman, Brokering Empire: Trans-Imperial Subjects between Venice and Istanbul (Cornell University Press, 2011), and for the latter, see Masha Kirasirova, Sons of Muslims in Moscow: Soviet Central Asian Mediators to the Foreign East, 1955’62 (Ab Imperio 2011 4, 106’32). Thanks to this revival in recent transnational history, the theme of brokers and brokerage (or its alternative formulations, such as ‘everyday diplomacy’) is re-entering the anthropological works of transnational scope. See Magnus Marsden, Diana Ibanez-Tirado, and David Henig, Everyday Diplomacy: Introduction to Special Issue (The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 2016 34 [2]).

[6] The alternative designation for this region, Azerbaijan, is contentious because of the entrenched competition between nationalist historiographies, which conflate state and society in a bounded territory. To avoid this puddle fight of competing parochialisms, we refer to the Azerbaijani homeland as Transcaucasia, which is a Russian demarcation for the lands beyond the Caucasus. Although its conventional use comprises the modern-day countries of Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia, we take the qualification ‘Trans-‘ more liberally to include northeast of Turkey and northwest of Iran, where Azerbaijanis have historical and contemporary presence.

[7] Ariv belgelerinde Osmanl─-─ran ilikileri. Ankara: Babakanl─k Devlet Arleri Genel M Osmanl─ Daire Bakanl, 2010, p. 1.

[8] This became evident during my field research among the Shi’a Azerbaijanis, who go in and out of Iran, Russia, and post-Soviet Azerbaijan.

[9] Atabeki, T., & Cronin, S. The Comintern, the Soviet Union and Working Class Militancy in Interwar Iran. Iranian-Russian Encounters. Empire and Revolution since 1800. Routledge, 2012, pp. 298’323.

[10] Hasanli, Jamil. At the Dawn of the Cold War: The Soviet-American Crisis over Iranian Azerbaijan,

1941’1946. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2006, p. 70.