By Muhammad Ismail Shogo

Introduction

The construction of tunnel passages that run underneath the Gaza Strip over the past decade or so has radically altered the political dynamic within the region and the international community this is evident in the newly-added nuances and changing trajectories that characterise the Gazan-Israeli relation. This paper will assess the Israeli position towards Gaza represented in media outlets. The Israeli state along with other hard-line media outlets have deliberately attempted to divert international attention away from the blockade imposed on Gaza by re-framing discourse that surrounds the tunnel trade. Israel has re-framed this discourse by specifically diluting local Gazan narratives that emphasise the economic exigency of tunnels a problem in itself created by the Israeli blockade in the face of the international community. This paper will analyse the tactics employed by the Israeli state in doing this via two primary means via the exaggeration of threat, and diplomatic coercion.

The distinction that exists between smuggling tunnels and what Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu calls ‘terror tunnels’ must be made clear from the outset. The former, refers to tunnels that operate from major cities in the Gazan Strip like Rafah into the Egyptian Sinai. These tunnels are used for the smuggling of goods into the Gaza Strip a direct response to the Israeli blockade that was imposed following Hamas’s victory in the 2006 Palestinian legislative elections that has hitherto withheld the trade of goods into Gaza.[1] This has significantly debilitated the Gazan economy, having shrunk Gaza’s GDP by 50 percent[2] – therefore forcing 80 percent of the population below the poverty line. Despite having been criticised as being tantamount to collective punishment, and therefore violating the Fourth Geneva convention, Israel has thus far refused a complete removal of the blockade on Gaza.[3] These smuggling tunnels, which have allowed for the movement of goods ranging from fundamental necessities like food and fuel to the most bizarre like zoological animals, have since then served as a bulwark against the blockade and the flailing economy.[4] The relief provided by these tunnels is noteworthy – having boosted Gaza’s trade revenue from $30 million a year in 2005 to $36 million a month.[5] The tunnels had also slashed fuel prices down to an affordable quarter of what Israel would charge in exports in 2009.[6] Traders of household goods have also reported a 60 percent increase in imports through tunnels from 2008 to 2010, including the provision of inputs that were vital in kick-starting Gaza’s post-war reconstruction process. By mid-2011, large quantities of construction materials like gravel and cement were arriving daily in Gaza through the tunnels. The effects of this were clearly exemplified when a 2011 report by the World Bank showed a construction growth of 220 percent in Gaza, with unemployment falling from 45 percent before Operation Cast Lead to 32 percent after.[7] This phenomenal success has led many to describe the smuggling tunnels as “the lungs through which Gaza breathes”.[8]

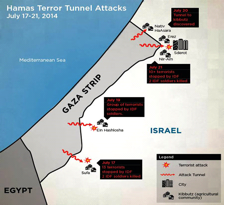

In contrast, ‘terror tunnels’ refer specifically to tunnels dug by Hamas operatives from within the Gaza Strip to infiltrate Israeli territory. By granting Hamas considerable leverage in conducting military offenses against the Israeli state, ‘terror tunnels’ have served as a significant game changer in the Hamas-Israeli struggle. In July 2014, by manoeuvring through ‘terror tunnels’ (See Figure 1, Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2014), Hamas was able to successfully penetrate the borders of Israel and conduct a series of terrorist attacks aimed at Israel. Their infiltrations took place near agricultural villages, Sufa, Ein HaShlosha, and Erez, near the Gazan borders, claiming the lives of six Israeli soldiers.[9]

Milena Sterio, The Gaza Strip: Israel, Its Foreign Policy, and the Goldstone Report, 43 Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 229 (2010)

(Figure 1: Diagram of ‘terror tunnels’ dug by Hamas that penetrate into the Israeli state)

Complications surrounding the two types of tunnels arose after Israeli intelligence discovered that Hamas operatives had been moving arms used against Israel from Egypt into Gaza via the smuggling tunnels. As a result, Israeli politicians and media outlets have turned towards employing tactics that would frame all tunnel activity in Gaza be it for smuggling goods or directly infiltrating the Israeli state as abetting Hamas’s terrorist agenda. This paper problematises these tactics as having diluted local non-Hamas Palestinian narratives that strongly emphasise economic urgencies specifically, the undisputed Gazan reliance on smuggling tunnels that contribute directly to the survival and welfare of the Gazan population. This is to say that Israel has trivialised the Gazan economic exigency in the face of Israeli’s own security concerns, a move that consequentially shifts focus away from the blockade itself to threats against Israeli security.

This Insight, however, does not vindicate Hamas for smuggling arms and weaponry through smuggling tunnels, nor does it attempt to deny the threats that smuggling tunnels when in the hands of Hamas for moving arms pose to Israel. Admittedly, rarely are distinctions between Hamas owned tunnels and tunnels owned by private enterprises black and white. Following the blockade, Hamas turned to the expanding tunnel economy as a primary source of revenue by decriminalising and subsequently imposing taxes on tunnels reportedly charging Gazans up to $6,000 for the privilege of beginning construction then (taxing) each tunnel $200 per month.”[10] Evidently, while Hamas does indeed regulate the tunnel trade, it would be dubious to assume that all smuggling tunnels are owned and operated by Hamas. Indeed, it has been reported in a testimony on the 2014 Gaza conflict that tunnels under Egypt are mostly if not wholly private enterprises’ constructed by families for business ventures.[11]

What this Insight aims to do, instead, is draw attention to the falsifying tactics Israel has employed through both the exaggeration of security threats as well as diplomatic coercion – that have lent to the dilution of Palestinian (non-Hamas) narratives of smuggling tunnels. In analysing these tactics, this Insight will then reveal how Israel has reframed discourse surrounding tunnel activity that diverts attention away from the blockade.

Exaggerating the Terrorist Threat

Adopting the Rhetoric of Terror

One tactic Israeli politicians and media outlets have employed in framing smuggling tunnels as ‘terror tunnels’ is via the adoption of political language that infuses the rhetoric of terror. The employment of such rhetoric in addressing tunnel activity between Egypt and Gaza have in the process blurred the distinctions between smuggling and ‘terror tunnels’, and therefore inadvertently exaggerates the threats posed by smuggling tunnels in the face of the international community. This was exemplified most conspicuously during a press conference in August 2014 in which Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu referenced an article by the Journal of Palestinian Studies as evidential support that documented Hamas’s use of children for working in terror’ tunnels – an assertion that was subsequently propagated by several pro-Israeli media outlets, including the Jerusalem Post, the Times of Israel as well as Huffington Post. The author of the article, Nicholas Pelham, however, later refuted Prime Minister Netanyahu’s claim and asserted that the tunnels in question referred specifically to commercial tunnels that connected Gaza to the Egyptian border. The article had also articulated that the majority of these tunnels were operated by private enterprises and not Hamas operatives.[12]

Israeli media has likewise been complicit in exaggerating the threat posed by Hamas through the adoption of the language of terror. From 2014 to 2016, the hard-line Israeli press organisation Arutz Sheva, better known in English as the Israel Nation News, published several articles with headlines that conspicuously infused terror rhetoric – ‘Egyptian Army Finds Rigged Terror Tunnel'[13], ‘Egypt floods Hamas Terror Tunnels'[14], ‘Egyptian Army Destroys 13 Hamas Terror Tunnels'[15] and ‘Days after Terror Tunnel Revelation, Egypt Lets Cement into Gaza.'[16] ┬¡ These articles, all of which refer specifically to smuggling tunnels and not tunnels dug into Israel, have employed the lexicon of terror and in doing so, have blurred the distinctions between the two types of tunnels in Gaza. This use of such rhetoric can similarly be observed amongst Hebrew-language articles by hard-line Israeli media outlets like Maariv and Israel Shelanu.

(Figure 2: A Hamas digger works in a tunnel used for smuggling supplies’)

Pro-Israeli press agencies operating beyond Israel have also sought to blur distinctions between smuggling tunnels and tunnels used for abetting terror through methods of obfuscation and at times, even blatant fabrication. In March 2016, Breaking Israel News published an article titled ‘Egypt Reports Gaza Tunnels Big Enough for Trucks’ in specific reference to smuggling tunnels that link Egypt and Gaza.[17] The article, however, ironically presents an image of a terror tunnel dug from Gaza into Israel, therefore contributing to a narrative that equates smuggling tunnels as being tantamount to ‘terror tunnels’ a claim that is evidently problematic. Such cases are not coincidental, with The Jewish Press publishing an article a month before titled ‘Gaza Terror Tunnel to Sinai Discovered by Egypt’ that presents an image of a man in a flooded smuggling tunnel captioned as A Hamas digger works in a tunnel used for smuggling supplies’ (See figure 2, The Jewish Press 2016) alluding to Hamas ownership and control over smuggling tunnels. [18] The image, originally photographed by independent photojournalist Abed Rahim Khatib and uploaded on FLASH90 a leading photojournalism agency operating in Israel was however significantly misrepresented. Khatib’s initial caption for the photo A Palestinian man works in a tunnel, used for smuggling supplies between Egypt and the Gaza Strip’ made no allusion to Hamas, begging the question as to whether or not the tunnels that had been flooded were indeed Hamas-operated tunnels or tunnels that been operated by private entities instead.[19]

By framing smuggling tunnels as having association with Hamas or tunnels that are being dug directly into Israeli territory – and by extension, the terror threats associated with such Israeli press outlets contribute to a dominating discourse that deliberately exaggerates security threats and shifts focus away from the reprieve smuggling tunnels have provided to Gazans. These cases of fabrication are few among many others which have attempted to intentionally mislead and re-shape public and international opinion surrounding discourse on smuggling tunnels in Gaza

Diplomatic Coercion

Israeli Pressure and Egyptian Policy: From Informality to Sabotage

The Israeli state has also resorted to more aggressive strategies by manipulating relations among state actors that have lent to the diversion of attention away from the blockade, and by extension the narratives that emphasise Gaza’s economic urgencies. These strategies allude to a form of diplomatic coercion that manifests primarily through diplomatic pressure on Egypt – often via the United States – that have consequentially compelled the Egyptian government to act in a way as though the threat posed by Hamas is substantially significant, despite evidence showing that this was not always the case. As a result, the past decade has presented a shift in Egyptian policy from balancing between Palestinian interests and regional security, to one that disregards Palestinian needs completely and in doing so, reframed discourse on tunnel activity that diverts attention from the Israeli blockade.

The early Egyptian position surrounding smuggling tunnels had often vacillated between humanitarian support and stricter border security, a dilemma that has been exemplified through Egypt’s informal policy of passive acceptance. This equivocal stance was underscored in a paper published in 2011 with the observation that Egyptian border administrators had often turned a blind-eye towards tunnel related smuggling.[20] The paper gave accounts of diesel-fuel tunnels that continued to remain open despite the movement of smuggling trucks that could have been easily identifiable by Egyptian border control. One statement revealed a routine whereby Egyptian authorities would fill a tunnel with cement, only for smugglers to then dig through the cement and re-open the tunnel a few days later. Based on these observations, the paper asserts that Egyptian authorities had been well aware of where tunnels are and what is being transported; especially if tunnels are re-opened and return to business post closure.’ The paper also cited smuggling safe’ roads where police checkpoints had been deliberately placed away from, despite having been within clear sight of Egyptian border control.[21]

This form of passive acceptance was exemplified not only among border administrators, but also along higher echelons of power particularly evident during a breach at the Egyptian border in 2008, where supporters of Hamas blew open several openings in the border fence from Rafah that allowed 200,000 Gazans to flood into the Egyptian Sinai.[22] The Egyptian Border Guard Force had however, refrained from exerting force against the Gazan crowds. Egyptian President Mubarak himself had also remarked I told them to let them come in and eat and buy food and then return them later as long as they were not carrying weapons’, a response that clearly exemplifies a policy of passive acceptance to the smuggling problem.[23]

Egyptian passive acceptance, that had earlier granted Gazans some form of economic leverage, had, however, begun to gradually wither away as a result of Israeli and US pressure. Following Hamas’s political victory in June 2007, Israel accused Egypt of inept border control along the ‘Philadelphi Route’ a thirteen-kilometre strip of land in Egypt that adjoins the Gaza Strip, that Hamas were smuggling advanced arms like Katyusha rockets, anti-tank weaponry and shoulder-held anti-aircraft missiles into Gaza.[24] Having failed to yield to her initial accusations, Israel then turned towards more aggressive forms of coercion – particularly by leveraging on her affinities with the United States to persuade the Egyptian government to tighten border security. In November 2007, Yuval Steinitz, member of the Israeli parliament (Knesset), wrote in letters to members of the U.S. Congress requesting for them to freeze military aid to Egypt. A month later, Israeli Foreign Minister, Tzipi Livni, asserted in her testimony in front of the Knesset that Egypt’s inability to control her borders with Gaza was terrible, problematic and damages the ability to make progress in the peace process.'[25] Israel then subsequently demanded that the United States impose conditionalities, geared specifically towards counter-smuggling initiatives, on her $1.3-billion-dollar military aid package to Egypt culminating in the Consolidated Appropriations Act in 2008 which allows the U.S. government to withhold from Egypt $100 million in Foreign Military Financing, unless the Secretary of State affirms that Egypt has contributed to initiatives that detect and destroy the smuggling network and tunnels that lead from Egypt to Gaza.’ The act marked the first in which Congress successfully imposed conditions on U.S. military aid to Egypt a move in which Israel had a substantial role in abetting. The Egyptian government has called the Israeli manipulation a deliberate act to sabotage’ relations between the United States and Egypt.[26]

Attitudes towards Gaza saw a turn in 2009 when Egypt, under U.S. supervision, began the construction of a twenty-five-meter-deep underground steel wall along her border with Gaza aimed at preventing the construction of more smuggling tunnels. By the end of 2010, Egypt had destroyed over six hundred tunnels through means of flooding passages with sewage and plugging entrances with solid waste.[27] In February 2016, the Egyptian military flooded more smuggling tunnels a move that Israeli Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz claimed was done to a certain extent at our request’.[28]

By manipulating regional dynamics and political affinities, Israel had succeeded in convincing Egypt, and the international community in quelling tunnel-related smuggling activity. This is evident by the gradual shift in Egyptian policy from careful balancing to sabotage a change that was motivated by Israeli pressure that threatened Egypt’s relations with other states. However, by forcing Egypt to act in a certain way that it would not otherwise have, Israel had succeeded in presenting to the international community the perceived level of threat posed by Hamas as being substantially high therefore changing the outlook of foreign powers on the Israeli-Gazan dynamic as one that downplays Gaza’s economic urgencies when confronted with Israeli security concerns. What this means is that Israel had succeeded in reframing discourse on tunnel related activity as one that centres on threats against Israeli security instead of the economic plight in Gaza, which by extension, diverts attention away from the illegal blockade.

Conclusion

The cases presented in this paper exemplify the tactics employed by Israel through diplomatic coercion and methods designed to exaggerate threats that trivialise local Palestinian narratives that emphasise economic reprieve provided by smuggling tunnel in Gaza. This, along with Israel’s disregard for nuance surrounding tunnel activity (in particular the distinctions between smuggling and ‘terror tunnels’, as well as the distinctions between Hamas-operated smuggling tunnels and those run by private entities) have consequentially lent to the creation of a new narrative that depicts an imagined level of threat posed by Hamas as being substantially high. This new narrative, that downplays the Gazan economic exigency, has however shaped discourse on tunnel activities in a way that absolves the Israeli state from responsibility of the blockade an intrinsic and significant element in truly understanding the dynamics of tunnel activity in Gaza.

Ismail Shogo is Research Assistant at the Middle East Institute and is currently pursuing his undergraduate studies in Political Science at the National University of Singapore where he will graduate from in 2019. His research interests lie in Middle Eastern and African politics and society.

[1] Carol Migdalovitz, Israel’s Blockade of Gaza, The Mavi Marmara Incident, and Its Aftermath,’ Congressional Research Service (2010): 236 -237

[2] Gaza Economy on the Verge of Collapse, Youth Unemployment Highest in the Region at 60 Percent,’ The World Bank, May 21, 2015, accessed June 24, 2016, http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2015/05/21/gaza-economy-on-the-verge-of-collapse.

[3] Milena Sterio, The Gaza Strip: Israel, Its Foreign Policy, And the Goldstone Report,’ Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 229 (2010): 236 -237.

[4] Harriet Sherwood, The KFC smugglers of Gaza,’ The Guardian, May 19, 2013, accessed June 15, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/shortcuts/2013/may/19/kfc-smugglers-of-gaza.

[5] Ghazi Surani,’Warqa Hawla: Infaaqa Rafha wa Aatharhaa Al-Iqtisaadiya wa Al-Ijtimaaiya wa Asiiyaasiiya (A Paper on the Economic, Social and Political Impacts of Tunnels in Rafah)’, Ahewar, December 14, 2008, accessed on 26 September 2016, http://www.ahewar.org/debat/show.art.asp?aid=156356.

[6] Nicholas Pelham, Gaza’s Tunnel Phenomenon: The Unintended Dynamics of Israel’s Siege,’ Journal of Palestinian Studies Vol. 41, No. 4 (2012): 15.

[7] Ibid 16.

[8] Ibid 10.

[9] Behind the Headlines, Hamas’ Terror Tunnels,’ Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, accessed July 21, 2016, http://mfa.gov.il/MFA/ForeignPolicy/Issues/Pages/Hamas-terror-tunnels.aspx.

[10] Brandy Castanon, The Tunnel Operations under the Gaza-Egypt Border in Rafah,’ School of Global Affairs and Public Policy (2006): 43.

[11] Eado Hecht, The Tunnels in Gaza, Testimony before the UN Commission of Inquiry on the 2014 Gaza Conflict,’ (2015): 21.

[12] A response to Netanyahu and a Correction from the Journal of Palestine Studies,’ Institute for Palestinian Studies, August 28, 2014.

[13] Egyptian Army Finds Rigged Terror Tunnel,’ Arutz Sheva, February 3, 2016, accessed June 18, 2016, http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/207456#.V3jo77h94fE.

[14] Egypt floods Hamas Terror Tunnels,’ Arutz Sheva, September 20, 2015, accessed June 18, 2016, http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/200859.

[15] Egyptian Army Destroys 13 Hamas Terror Tunnels,’ Arutz Sheva, July 27, 2014, accessed June 18, 2016

http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/183388.

[16] Ari Yashar, Days after Terror Tunnel Revelation, Egypt Lets Cement into Gaza,’ Arutz Sheva, May 13, 2011, accessed June 19, 2016, http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/212224.

[17] Adam Eliyahu Berkowitz, Egypt Reports Gaza Tunnels Big Enough for Trucks,’ Breaking Israel News, March 11, 2016, accessed June 18, 2016, http://www.breakingisraelnews.com/63407/egypt-reports-gaza-tunnels-big-enough-for-trucks-terror-watch/#LBGPfpZw0uTbEkg3.97.

[18] Hana Levi Julian, Gaza Terror Tunnel to Sinai Discovered by Egypt,’ The Jewish Press, February 13, 2016, accessed June 21, 2016, http://www.jewishpress.com/news/breaking-news/new-gaza-terror-tunnel-to-sinai-discovered-by-egypt/2016/02/13/.

[19] Abed Rahim Khatib, Flash90, October 1, 2015, accessed June 25, 2016, http://www.flash90.com/fotoweb/archives/5001-Flash90%20Archive%20%20Photos/Flash90_2010/2012-103/F151001ARK07.jpg.

[20] Brandy Castanon, The Tunnel Operations under the Gaza-Egypt Border in Rafah,’ School of Global Affairs and Public Policy (2006): 63.

[21] Ibid 72.

[22] Jeremy M. Sharp, The Egypt-Gaza Border and its Effect on Israeli-Egyptian Relations,’ Congressional Research Service (2008): 9.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid 6.

[25] Ibid 6.

[26] Ibid 1.

[27]Nicholas Pelham, Gaza’s Tunnel Phenomenon: The Unintended Dynamics of Israel’s Siege,’ Journal of Palestinian Studies Vol. 41, No. 4 (2012): 13.

[28] Manpreet Sohanpal, Iran, Iraq, Syria and the Gulf,’ in The Week in Review, February 8 February 14, Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses (2016): 19-20.