By Veronika Deffner and Carmella Pfaffenbach

Since the growth and development of the oil sector in 1967 and with the coming to power of Sultan Qaboos bin Said al Said in 1970 (who continues to lead today as the longest ruler of the Gulf states), Oman has experienced an era of intense and rapid modernisation. This process encompasses economic development and countrywide investment in technical infrastructure (roads, buildings etc.), as well as social infrastructure (schools, hospitals etc.).

Since Qaboos put an end to the international isolation and oblivion of the country under his father’s auspices (Sultan Said bin Taimur) in the 20th century, the city area and its surrounding region have been undergoing an almost unprecedented process of urbanisation (see e.g. Peterson 2004). The city is the country’s most important economic hub and has the highest demand for labour. Therefore, the majority of foreigners, which account for 44 percent of the total population in the country, are concentrated in the Capital Area of Muscat (see NCSI 2014).

The six-nation Gulf Cooperation Council (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (GCC) have seen different waves of immigration within the oil-modernisation years. In the early stages, employees were mainly recruited from other Arab countries such as Egypt, Yemen, Sudan, and Morocco. Hence, in 1975, three-quarters of all migrant workers in the GCC were Arabs. Since the 1990s, following the Gulf war, the countries of origin shifted decisively: the labour force has been increasingly and predominantly recruited from South and Southeast Asia. Until today, Asian communities still make up the largest group of migrants in Oman: amongst all expatriate workers with valid labour cards in the private sector in Oman in 2013, 44 percent were from India, 33 percent from Bangladesh, 17 percent from Pakistan, and 1 percent from the Philippines (NCSI 2014: 146). Therefore, Asian migrants currently represent over 90 percent of all non-nationals living and working in Oman. Likewise, the category ‘other nationalities’ in the census, including all western expatriates from Europe, the US, Australia etc., only has a share of 3 percent of the total population, according to data from Oman’s National Centre for Statistics and Information (NCSI 2014: 146).

This Insight aims to analyse the spatial and social consequences of the coexistence of heterogeneous groups, with regard to nationality and socio-economic position in Muscat. Against the backdrop of the political and institutional structures in place governing international migration to the Sultanate of Oman, including the objectives and challenges of Omanisation, we will discuss how the urban society of Muscat is created in terms of socio-spatial structures and the integration (or non-integration) of foreigners. The paper closes by tackling the question of whether integration is possible, and if so, in which segments of society.

The Political and institutional context of economic migration to Oman

The strong pull that the Sultanate of Oman exerts on migrants from many parts of the world can be attributed to the general reality of economic migration, that migrants can expect better pay, a higher quality of life, and better chances of advancement in Oman than in their countries of origin. The proximity of Southeast Asian home countries to the Gulf plays an additional role, as migration costs are lower and even low-income migrants can afford to travel home, even if it is often only once every two years.

Labour market structures

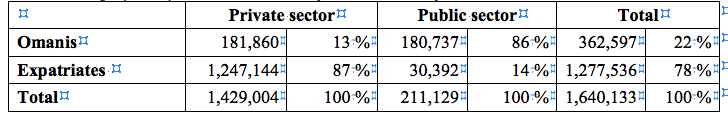

In 2013, 87 percent of the total labour force in the private sector of Oman was made up of foreign workers, while only 13 percent were Omanis (NCSI 2014: 97). In contrast, the public sector is by and large in the hands of Omanis, who account for 86 percent of employees (see Table 1).

Table I: Employees by economic sectors of the Sultanate of Oman 2013

(Source: NCSI 2014: 97; own calculations)

As is true for all GCC States, the Omani labour market is not one that is free, even in the private sector, but instead pursues a policy of targeted workforce recruitment and is characterised by a strong structural dependency of employees on their employers. These employers, or ‘sponsors’, are legally and economically responsible for their employees. They register the contractual relationship to the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour, and apply to the Department of Immigration for a working visa and residence permit for their employees.

This contractual and personal bond to the sponsor has particularly grave consequences for contract and domestic workers (see Bajracharya/Sijapati 2012). Not only do they work long hours for marginal wages, but they are also entirely beholden to their employer, with personal freedom and mobility being severely restricted by being required to surrender their identity and residence documents (passport and visa) when the employment relationship commences. Consequently, it is not only very difficult or even impossible for employees to terminate their employment in the event of a violation of their labour and migrant rights, but it is also not possible to even look for another job or to return to their home country. Employees dismissed by their employer immediately find themselves being sent back to their home country or having to assume an illegal status. The imbalance between the obligations of employees and the services and remuneration provided to them by their employers has also been sharply criticised by the International Labour Organization (ILO) (see ITUC 2008).

The labour market in the Sultanate today is decisively hierarchical and distinctly segmented. At the apex of the private sector are a small number of well educated experts, who earn the highest salaries and enjoy the greatest privileges. In terms of salary, they are followed, respectively equated, by locals. ‘Below’ them on the income scale are migrants from Arab countries and from East and Southeast Asia. Even if the latter were to work in similar positions as expatriates from countries such as North America, Europe, Australia, South Korea or Japan or local employees, they would still command a lower wage. However, in terms of the sheer number of workers, this hierarchy forms a characteristic pyramid with a quantitatively large base of less qualified low-income migrants from East and Southeast Asia.

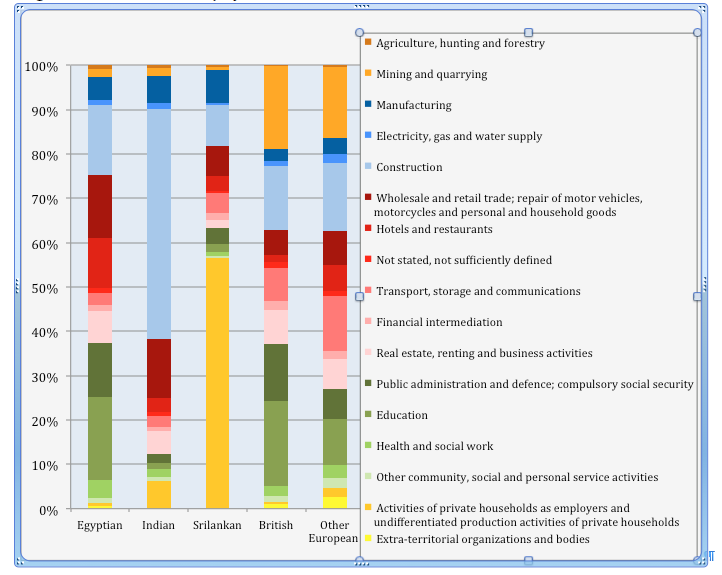

The correlation between the country of origin of a migrant worker and his/her position in the labour market is also illustrated in Figure 1. As the statistical data indicates, the majority of foreign workers from Southeast Asian countries are employed in the construction industry, in manual-labour jobs, and as domestic workers, while Egyptian and British workers are employed in large numbers in the education and public administration sectors. Exceptionally large numbers of well educated specialists[1] are employed in “mining and quarrying”, meaning effectively that they work for the national and international oil and gas companies.

Figure 1: Economic activity of selected nationalities in Muscat

(Source: Own calculations of census data 2010 by the Ministry of National Economy)

Undoubtedly, the hierarchical and segmented labour market is directly reflected in the segmented urban immigrant society. At a glance, the changes within the population statistics over the last decades show clearly how the Capital Area of Muscat has developed into a culturally globalised place: in 1970, the greater capital area had approx. 50,000 inhabitants; in 1980, it had grown to approx. 226,000 inhabitants, amongst them 108,000 non-Omanis (Scholz 1990: 162); and in 2010, 776,000 people lived there, of whom 48 percent were foreigners.

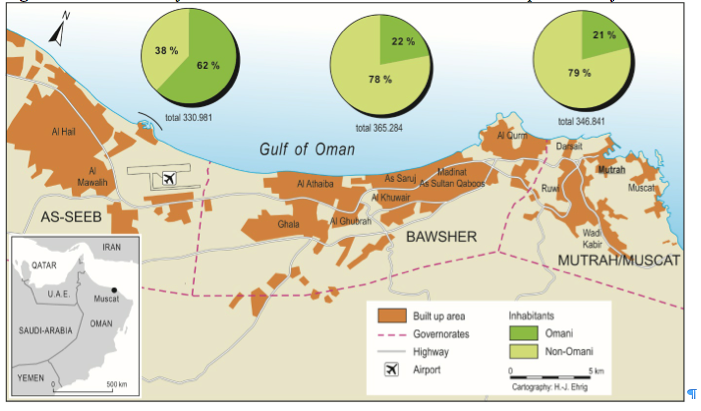

The number of expatriates has continuously grown countrywide since the mid-1970s, and today 1.7 million foreigners live in the Sultanate, which is equivalent to 44 percent of the overall population (3.9 million inhabitants). While these figures illustrate the dynamic growth of foreigners living and working in Oman, the growth is disproportionately concentrated in the Capital Area of Muscat, where 61 percent of the population (or 704,000 of 1.2 million inhabitants in total) consists of expatriates. Figure 2 illustrates that the rate of social heterogeneity in Muscat is especially high in the administrative provinces Mutrah/Muscat and Bawsher, where the proportion of non-Omanis in 2013 reached approximately 80 percent (NCSI 2014: 69).

Figure 2: Distribution of national and non-national inhabitants in the capital area of Muscat

(Source: Apex Map of Muscat (2012) and NCSI 2014: 69)

Despite the rapid pace of urban growth and the marked cultural and ethnic heterogeneity of the population in the Capital Area of Muscat, the city has seen neither the rise of precarious or infrastructurally deprived neighbourhoods, nor marginalised or socially discriminated quarters. All in all, there are only a few signs of either disintegration or racial and national segregation, which will be discussed later in more detail.

Omanisation of the labour market

Despite the endeavours to nationalise the labour market, which were already initiated in the National Development Plan in 1988 (see Al-Lamki 2000), the proportion of non-Omani employees in the private sector has continued to rise over the last decades. In 1985, they accounted for 52 percent of private sector employees and, in 1995, 64 percent (see United Nations Expert Group 2006: 16), and 87 percent in 2014. This prompted a new intensification of the so-called Omanisation policies in the last two years.

Efforts at nationalising the workforce appear to be failing, particularly in the private sector, in spite of the introduction of normative quotas for Omani employees in twelve economic sectors ranging from, for example, 20 percent in wholesale to 60 percent in transport and communication and up to 100 percent were targeted in jobs such as department managers, TV cameramen, accounts clerks, or newspaper vendors (see Das/Gokhale 2010). The most attractive jobs for Omani employees are considered to be in the banking, finance, and real estate sectors, as well as in the telecommunication, travel and tourism sector. In these areas, the Omanisation quota has been set around 90 percent in operating, marketing, sales, supervisory, or other representative management positions. Other sectors, which are more difficult to nationalise, in particular due to the technical skill requirements, include the oil and gas sector, which shows a significant lower quota of only 30 percent in 2010. The schooling and educational sector is another area that is difficult to omanise, hence the aimed quota was only 15 percent in 2010 (Ministry of Manpower 2014). Reliable data about the achieved Omanisation quota are lacking. Although all companies in the private sector have to report annually their employment statistics; there is still a high blurring of the de facto replacement of foreign workforce by local nationals. Instead, there are high numbers of double-employment, for example to keep foreign employees to run businesses and to employ Omanis as a matter of form.

However, it should not be overlooked that a large number of jobs in the private sector are low-skill jobs with pay and working conditions that are unattractive or even unacceptable for Omanis. Consequently, in the aftermath of the Arab Uprisings, the protests in Oman in 2011 addressed, aside from the call for political reforms, the grievances in the public sector. These included unemployment, unsatisfactory employment and income opportunities for Omanis, as well as favouritism and corruption (see Valeri 2015: 10). In response, the government introduced a minimum wage and a 45-hour working week designed to make the booming sectors (construction, tourism and real estate development, electricity and water, environmental technology, etc.) more attractive to the indigenous workforce. The continued growth in the proportion of expatriates in the private-sector workforce in 2011 and 2012 could be behind the renewed increase of the minimum wage in July 2013.

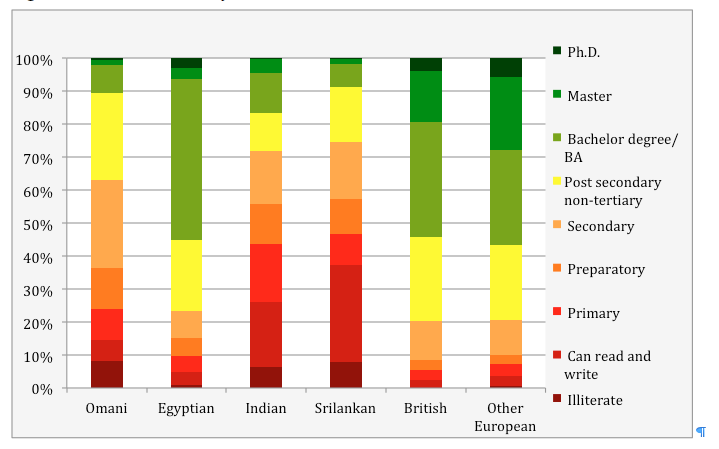

Figure 3 illustrates the continuing high dependence in Oman on international expertise and technically-skilled employees who possess tertiary educational degrees (Bachelor, Master, or PhD) or post-secondary/non-tertiary education, which means they hold a secondary education and have enjoyed specific vocational training. The most obvious discrepancy in terms of education levels exists between Omani nationals on the one hand, and Egyptian or “Western”[2] nationals on the other. One caveat, must, however, be mentioned at this juncture: that the age structure of the selected nationalities in the graph varies considerably, but is not respected in the statistical data. Nevertheless, the age has a significant influence on the level of education: while a large proportion of the young Omani population is still in education and training, the overriding majority of the expatriate community are of working age and have therefore already completed their education and training.

Figure 3: Educational level of selected nationalities in Muscat

(Source: Own calculations of census data 2010 by the Ministry of National Economy)

Muscat’s heterogeneous urban society

The production and representation of Muscat’s heterogeneous urban society can be examined from two dimensions: socio-spatial segmentation and integration.

Socio-spatial segmentation

Socio-spatial differentiation by nationality, including Omanis, as described by Scholz (1990) for the 1980s, can no longer be validated as a basic category in Muscat. Today, the urban space is merely subdivided into quarters in accordance with the different rental and purchase prices.

The practical reality of the choice or allocation of the place of residency has resulted in relatively small-scale heterogeneity within the respective neighbourhood. However, the spatial concentration of certain income groups across the entire urban area is scattered and seems to follow a more small-scale heterogeneous pattern of individuals of different socio-economic positions. In a household of four or more wealthy Omanis or expatriates, it is very often the case that at least two domestic employees ‘ who live separately in small rooms in the wings of the residential houses ‘ also need to be counted.

Nevertheless, the spatial practicality of choosing the place of residence occurs in accordance with individual preferences and pragmatic considerations, e.g. the distance to the workplace, to childrens’ schools, , or to other important facilities.

Integration

The question of integration in the urban society in Oman needs to be considered in a way that is detached from the classic paradigm of assimilation (e.g. Esser 2008), as assimilation is not possible by virtue of the inherent social principle or power of the hosting Omani society. One reason for this is that the residency permit is directly dependant on the employment contract, which can be terminated at any time by the employer. Social welfare payments from the state are reserved, for the most part, for national citizens. In addition, the naturalisation of foreigners is only possible in exceptional cases.

The structural integration of foreigners takes place predominantly through the job market, which also determines, in a way that is evident for all involved, the social position of each individual. The often-praised “welcoming culture” of Omani society towards guests, however, only extends its interpersonal recognition to highly-qualified professionals. In order to differentiate the permanent integration of foreigners from the limited stay of transnational migrants, the term “incorporation” is occasionally used. The indicators that determine what is classified as (non)integration and (non)incorporation are, however, the same (see Yeoh 2006, Glick Schiller/─ƒlar 2009), and it is for this reason that the established term “integration” has been given preference here.

Despite the fact that Omani society demands cultural hegemony for itself, it still allows a limited degree of diversity to exist. On the one hand, this entails allowing foreigners the freedom to live the lifestyles they choose, as long as they adapt and adhere to local behavioural norms in public spaces (e.g. ban on alcohol, appropriate clothing, discreet demeanour). On the other hand, migrants of different religious faiths are allowed to practice their religion and to erect religious buildings such as temples and churches ‘ as long as financing is provided by its own religious community. The individual willingness on the part of migrants to make such an investment in a place in which they will only live for a limited period of time, however, is rare.

At the same time, an image is being cultivated in Oman which aims to downplay the very presence of foreigners in the country and their contribution to the modernisation of the economy and society. In this respect, the issue of ethnic-cultural diversity in view of the heterogeneous population is not broached, even in temporary terms. Due to the statutory provisions in place in Oman, foreign workers are only in the country on a temporary basis, and it is for this very reason that the issue of integration is of no importance, from the Sultanate’s perspective.

Conclusion: temporary integration for transnational migrants

In order to answer the questions of whether or not -and in which segments of society-integration is possible, the following conclusion can be drawn.

The Omani host society clearly reduces its migrants to the practical purpose of their labour, just like other Gulf countries. Immigration in any form is welcome only if it is temporary. Permanent immigration that extends to assimilation, wherein any kind of ethnic difference disappears as a result of adaptation on the part of the migrants, and naturalisation, are not desired.

Therefore, social integration opportunities for transnational migrants are extremely restricted, with structural integration into the labour market and socio-economic positions becoming the decisive factor. The host society as a whole is not available as a point of reference for social integration, but only that segment of the heterogeneous society which is accessible to the migrants based on their individual economic, social and cultural assets. Hence, lower skilled migrants, domestic workers and others who have limited mobility and restricted time and money disposability, generally live and meet with likewise-situated people. Language, religion, and cultural practice, which are all comprised in one’s social status, are the utterly important categories for feeling socially comfortable and accepted ‘ and thus, having access to specific segments of the whole society (foreigners and locals included). However, in particular nationality, language and cultural practice are blurring as significant distinguishing categories towards the high earning or high-skilled end of the social hierarchy. Social encounter and exchange is more common on that upper social level, even though formal social integration (e.g. through inter-cultural marriages, de-sol citizenship etc.) remains a very rare exception.

However, most foreign employees perceive the Omani host society as tolerant, polite, down-to-earth, and helpful, especially in comparison to other recruiting GCC-countries: Omanis, in general, are held in high regard, because they participate in professional life. Critical voices, however, do point to a conflict specifically in the lack of technical skills, or other required expertise or vocational training, in a deficiency of international business experience, etc.

Although, the job requirements in the private sector are different, particularly when it comes to personal responsibility, creativity, and motivation ‘ indispensable skills for the most sought-after leading management and operating positions in the private sector. The lack of self-motivation and the dedication to work is often criticised as one of the biggest challenges for employable Omani (OER 2012).

This raises the final question as to what can be learned from the openly segmented immigrant society of Muscat, in spite of the multiple disintegration processes that can be observed and an immigration policy that has been designed to be temporary. On the one hand, segmentation of the many “worlds” of transnational migrants extending even to ‘parallel societies’, which are living side by side without any social or cultural exchange or interest, is tolerated, while in other (Western) contexts, segmentation is almost instinctively demonised as a risk to social stability and cohesion, although it is highly representative of urban reality.

From an Omani perspective, tolerance can be considered as the recognition of differences in terms of the lifestyle and religious and cultural orientation of expatriates during their stay in Oman. On the other hand, the host society may well be giving transnational migrants precisely what they expect, as it never adopts the paradigm of assimilation into social and political discussion: better pay than in their home countries, a high quality of life, and the freedom to live one’s own lifestyle and practice one’s religion. In other words, it signifies temporary integration for a life in transition.

References

Al-Lamki, Salma. ‘Omanization: A Three Tier Strategic Framework for Human Resource Management and Training in the Sultanate of Oman.’ Journal of Comparative International Management 3 (2000).

Bajracharya, Rooja, and Bandita Sijapati. ‘The Kafala System and Its Implications for Nepali Domestic Workers.’ Centre for the Study of Labour and Mobility Policy Brief 1 (2012):1-16.

Das, K. C. and Nilambari Gokhale. ‘Omanization Policy and International Migration in Oman.’ Middle East Institute: Washington, February 2, 2010. Accessed June 9, 2015. http://www.mei.edu/content/omanization-policy-and-international-migration-oman.

Esser, Hartmut. “Does the ‘New’ Immigration Require a ‘New’ Theory of Intergenerational Integration?” In Migration Theory. Talking Across Disciplines, edited by Caroline. B. Brettell and James. F. Hollifield, 308-341. New York: Routledge, 2008.

Glick Schiller, Nina. and Ayse. ─ƒlar. ‘Towards a Comparative Theory of Locality in Migration Studies: Migrant Incorporation and City Scale.’ Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (2009): 177-202.

International Trade Union of Confederation. ‘Internationally-Recognised Core Labour Standards in the Sultanate of Oman.’ Report for the WTO General Council Review of Trade Policies of the Sultanate of Oman, Geneva, June 25-27, 2008. Accessed June 9, 2015. http://www.ituc-csi.org/IMG/pdf/TPR_Oman.Final.pdf.

Ministry of Manpower. ‘Omanisation per Sector.’ Accessed June 9, 2015. http://www.manpower.gov.om/portal/en/OmanisationPerSector.aspx.

National Centre for Statistics and Information (NCSI). ‘The Statistical Yearbook 2013.’ Accessed June 6, 2015. http://www.ncsi.gov.om/NCSI_website/book/SYB2014/contents.htm

Oman Economic Review (OER). ‘Towards Nationalisation.’ Accessed June 9, 2015. http://www.oeronline.com/php/2011/Aug/casestudy.php.

Peterson, J. E. ‘Oman: Three and a Half Decades of Change and Development.’ Middle East Policy 11 (2004):125-137.

Scholz, Fred. Muscat. Sultanat Oman. Geographische Skizze einer einmaligen arabischen Stadt. Berlin: Das Arabische Buch, 1990.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. ‘International Migration in the Arab Region.’ UN Expert Group Meeting on International Migration and Development in the Arab Region: Challenges and Opportunities, Beirut, May 15-17, 2006. Accessed June 9, 2015. http://www.un.org/esa/population/meetings/EGM_Ittmig_Arab/P14_PopDiv.pdf

Valeri, Marc. ‘Simmering Unrest and Succession Challenges in Oman.’ Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 2015. Accessed June 9, 2015. http://carnegieendowment.org/files/omani_spring.pdf.

Yeoh, Brenda. S. A. ‘Bifurcated Labour: The Unequal Incorporation of Transmigrants in Singapore.’ Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 97 (2006): 26-37.

The above presented findings are based on a previous journal publication:

Deffner, Veronika and Carmella Pfaffenbach. ‘Urban Spatial Practice of a Heterogeneous Immigration Society in Muscat, Oman.’ Trialog, A Journal for Planning and Building in the Global Contexts 114 (2015) Oman: Rapid Urbanisation: 9-15.

Veronika Deffner is a social and cultural geographer, currently working as a Visiting Senior Research Fellow at the Middle East Institute at the National University of Singapore. Before, she was working as a Visiting Assistant Professor at the German University of Technology in Muscat and at RWTH Aachen University in Germany. Her research covers social, cultural and political aspects of international migration that connects the GCC countries and South/ Southeast Asia. She is particularly interested in nationalisation processes, cities and the rising tensions due to questions of integration, segregation and identity in the heterogeneous Gulf societies.

Carmella Pfaffenbach is Full Professor at RWTH Aachen University at the Department of Geography teaching Cultural and Urban Geography with a focus on heterogeneous urban societies. She holds a PhD from the University of Erlangen and a Habilitation from the University of Bayreuth (Germany). Throughout her academic career she has been visiting professor at Universities in Munich/Germany, Vienna/Austria, Rabat/Morocco and at GUtech/Oman. Her research focus is on migration and urban fragmentation in Europe, Northern Africa and the Middle East.

[1] Mainly from countries such as North America, Europe, Australia, South Korea or Japan.

[2] Western here is used synonymsly for countries in North America, Europe, Australia, South Korea or Japan and other economically advanced countries.