By Linda Matar

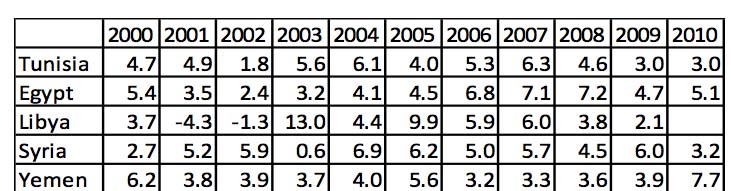

Three years after the start of the Arab Uprisings, the political landscape is that of political turmoil, counter revolutions, and civil war. To date, the policy agenda fails to confront the region’s deep-rooted socioeconomic problems that contributed to the immiseration of Arab masses and the making of rebellion. This Insight addresses a certain aspect of the underdevelopment quagmire, which is faltering Arab productive capacity. Prior to the uprisings, Tunisia, Syria, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen, all exhibited an average annual growth rate of 5 percent during 2000-2010 (see Table 1). However, this economic growth was neither inclusive nor did it benefit the poorer strata of society. In view of declining manufacturing capacity, Arab economies exhibited a growth performance that failed to promote decent employment opportunities. Employment generation, one may recall, is key to poverty alleviation.

Table 1- GDP growth rates of Arab countries, 2000-2010.

Source: World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2013)De

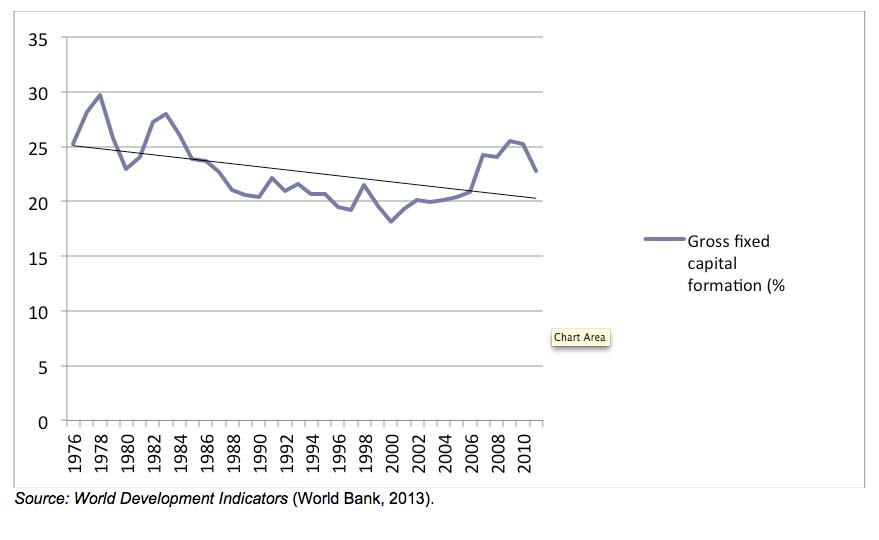

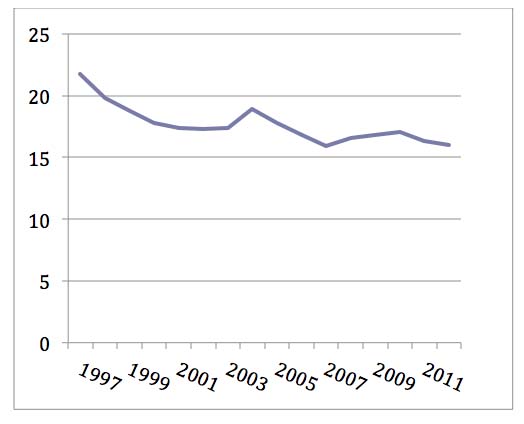

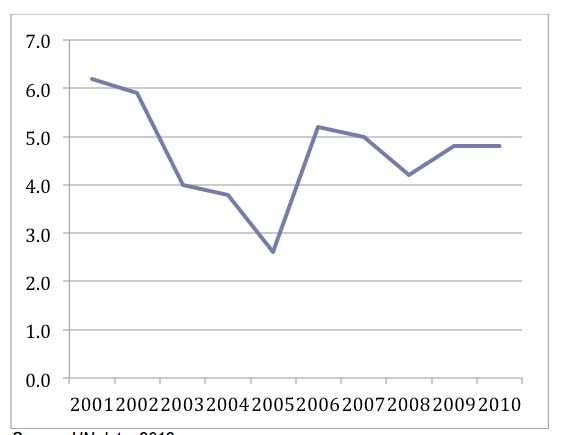

The Arab world has witnessed a decreasing trend in the rate of investment (Figure 1). The key driver of economic growth is productive investment or investment in new technology, plant and equipment.[1] Employment growth arises from productive investment or that which incrementally adds to non-labour saving capital stock. It follows, then, that, the prospect of growth stimulates new net investment and new investment in turn stimulates further growth. In this circular process, if new technology is introduced exogenously or developed endogenously, the economy gets locked into a virtuous circle by which high investment levels repeatedly enhance economic performance. At a general level, new firms will hire more workers, which leads to more employment and more demand for consumer goods. In the absence of significant external leakages, fluctuation in macroeconomic output’or what is known as a business cycle’is generated from the basic interaction between investment and the latter’s amplified effect on output through the multiplier effect. More importantly, increasing investment not only creates effective demand and galvanise the utilisation of resources, but it also builds productive capacity, generating more goods and more wealth. Thus, the underdevelopment problematic can be safely reduced to a capacity problematic. The overriding macroeconomic challenge in the developing world is that of increasing investment in order to engage their idle resources and develop their weak productive capabilities.[2] Therefore, building capacity in an underdeveloped Arab world is crucial. In order to move beyond the weak economic structures, Arab economies need to expand their industrial production and mobilise real and financial economic resources as a way to mitigate foreign dominance and initiate their own induced and independent path to economic development. However, an empirical reading of Arab investment and output behaviour reveals that the opposite of this recommended development strategy had happened. Investment in the Arab world witnessed high rates (29.4 percent) during 1977-1982 after which they started to decline till 2000.[3] The Arab investment rate fell from a peak of about 30 percent in 1978 to 20 percent in 1990, further decelerating to a low of 19 percent in 2000 (Figure 1). This drop rides on three interrelated components: political instability in the Arab world, the low rates of return on investment due to the small market size of Arab economies and the weak intra-regional integration. The outstanding risk component (internal and external) has kept private investors risk-averse and reluctant from investing in the region’except for the hit and run and the speculative types of business opportunities. This undermined the integrity of the Arab business cycle and increased leakages, especially in the instance where portfolio funds from the region were divested abroad. Starting in 2000, the investment rate has increased up until 2010 (25 percent) and fell afterwards (see Figure 1). The leap into the market-driven economic order, witnessed in many Arab countries has promoted private sector-led investment, while public investment in social infrastructure retreated. Arab policy makers promoted what is known as FIRE types of investment (finance, insurance, and real estate) ahead of others. This investment generates little output per capita invested and it fails to build the weak productive capacity. Moreover, with such little value added activity, few skill enhancing job opportunities are created. Under the free market model, the manufacturing rate dipped below 10 percent in the Arab world: as a percentage of GDP, manufacturing constituted 9.3 percent in 2010.[4] Meanwhile, the average investment rate was 19 percent for Egypt and 22 percent for Syria over the period 2000-2009.[5] While the Egyptian manufacturing output’s share out of total value-added production was 21.8 percent in 1997, the rate has been decreasing ever since, reaching 17 percent in 2009 and 2010 (see Figure 2).[6] Syria’s manufacturing share remained less than 10 percent during 2001-2010 (see Figure 3), whereas Tunisia’s manufacturing share remained almost constant during the same period, hovering around 18-19 percent.[7] Consequently, the past decade or so witnessed the rise in informal and low productivity service employment,[8] implying that the macroeconomic ‘stabilisation strategies’ failed to reverse the shortages in capital equipment. The productive capacities of Arab economies remained deficient in both scope and scale, meaning that the necessary qualitative backward and forward linkages failed to materialise. On the human resources side of the capacity equation, the high levels of cyclical unemployment demobilise considerable human productive assets.[9] The issue in the Arab world is not one of compatibility between demand for workers and the qualifications of workers, but one in which demand for workers is so low, such that, investment in education and health in the labour force remains idle or manifests itself as a fiscal leakage as a result of labour drain. In the absence of decent jobs and welfare nets as a result of neoliberal reforms, bare survival necessitates that labour force be engaged in poverty wage informal activity. The International financial Institutions (IFIs) peddled a policy that created the sort of jobs that run counter to their mandate as promoter of human rights and decent standards of living.

Figure 1- Investment rate in the Arab world, 1976-2011

Source: World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2013).

Figure 2- Egypt’s manufacturing share of total value added output, 1997-2012

Source: UN data, 2012

Figure 3- Syria’s manufacturing share of total value added output, 2001-2010

Source: UN data, 2012

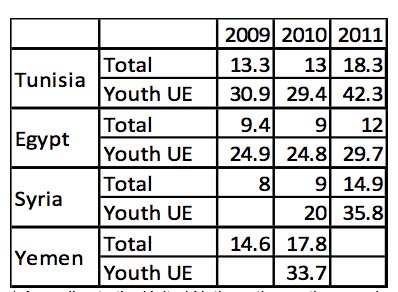

Post-uprising Arab economies maintained the old policy structures. Instead of radically addressing the socioeconomic problems that underpinned the social tension, they continued to promulgate unregulated market policies. In countries that did not slide into civil war (as in Tunisia and Egypt) Western intervention meant to support a democratic transition further strengthened the undemocratic economic policies that created huge rifts in society. Macroeconomic stabilization strategies remained set on short-term budget balancing and debt service, whereas development requires long-term financing and investment. A cursory look at the economic and social indicators of the post-uprising period reveals the persistence of the old damning trends. Although the quality of data leaves much to be desired, the combined GDP growth rate in Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Palestine dropped from 2.2 percent in 2011 to negative 1.7 percent in 2012. The wars in Syria and Iraq have had devastating consequences, but they have also written off a significant portion of Arab productive capacity. Poverty in the Arab Mashriq increased from 1.3 percent in 2010 to 5.7 percent in 2012.[10] Yemen’s poverty rate in particular increased from 40.1 percent in the 1990s to 44 percent in 2012/13.[11] Recent available data on unemployment shows that the unemployment conditions worsened. Unemployment rates in Tunisia, Egypt and Syria increased in 2011 as compared to 2010 (refer to Table 2). Both Syria’s and Egypt’s unemployment rates jumped into double-digit levels in 2011. Unemployment in general and that of the youth in particular, which was touted as a main cause of the uprisings, has gotten worse. Youth unemployment was twice or three times as high as total unemployment (refer to Table 2). On another front, the consumer price index heated up in the Arab Mashriq as it increased from 7.6 percent in 2011 to 11.4 percent in 2012.[12] However, inflation of a subset of basic commodities reached 20 percent’further dampening the purchasing power of the low income earners. Against this backdrop, it can be concluded that in terms of broad economic indicators, the post-uprising Arab economies are in worse conditions under their new regimes as compared to their anciens ®gimes. Table 2- Total and Youth Unemployment Rates for selected Arab countries, 2009-2011*

* According to the United Nations, the youth unemployment refers to unemployment of the age group (15-24 years, inclusive)Source: United Nations Statistical Bulletin 2013; Tunisia’s data is taken from World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2013)Latest figures on investment rates shows that the Arab world’s rate fell from 25 percent in 2010 to 23 percent in 2012’in particular, Egypt’s rate decreased from 19 percent in 2010 to 16 percent in 2012, whereas Tunisia’s rate fell from 24 percent in 2010 to 22 percent in 2011.[13] Foreign direct investment to Egypt was decimated, as it dropped from $6.4 billion in 2010 to a mere $500 million in 2011.[14] Deficient productive capacities that needed to be turned around became more deficient. State intervention is indispensable in this transitory phase, particularly to mitigate the impact of economic disruption and the decline of long-term commitment of private investment. Arab states need to stabilize and regulate total investment by increasing public investment. Keynes stated in the ‘The End of Laissez-Faire’[15] that ‘many of the greatest evils of our times are the fruits of risk, uncertainty and ignorance,’ and thereby called for public policy to be a forceful measure in building the productive capacity. State-led investment’increasing autonomous investment’becomes central, especially when the issue of volatility of private investment is raised in order to undermine the impact of hit-and-run types of investment. This would require a radical shift in the Arab countries’ macroeconomic growth strategies. Building productive resources should constitute the heart of development and poverty reduction policies, because these strategies can create labour-intensive projects that can resolve the problem of unemployment. In the absence of such strategies, the Arab Uprisings, unfortunately, may not produce social and economic progress.

Linda Matar is a Research Fellow at MEI. Her research involves the political economy and economic development of the Arab Near East with particular emphasis on Syria. She obtained her Ph.D. in Economics from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. Her research at MEI will focus on the political economy of the Arab Spring. Her recent publication is entitled ‘Twilight of ÔÇÿstate capitalism’ in formerly ÔÇÿsocialist’ Arab states’ (The Journal of North African Studies, 2013).

[1] Hicks, J.R., 1950. A Contribution to the Theory of the Trade Cycle (London: Oxford University Press) and Harrod, R.F., 1936.The Trade Cycle (London: Oxford University Press).

[2] Kalecki, M., 1976. Essays on Developing Economies (Hassocks: Harvester Press).

[3] World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2013).

[4] Joint Arab Economic Report (Arab Monetary Fund, 2011).

[5] World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2013) and Syrian Statistical Abstract (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2012).

[6] UN data, 2012

[7] UN data, 2012

[8] Recent estimates on informal employment out of total non-agricultural employment stood at 35 percent in Tunisia, 45.9 percent in Egypt, 30.7 percent in Syria, and 51.1 percent in Yemen during 2000-2007 (see Table 3.9 in United Nations Survey of Social and Economic Development in the ESCWA region 2012-2013).

[9] Over the last decade, the Arab countries have invested in their human capital stock as evidenced by the high and medium levels of Human Development Index (HDI) in 2011 (UNDP’s Human Development Data for the Arab States Database –http://www.arab-hdr.org/data/query/).

[10] United Nations Survey of Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, 2012-2013, pp. 36

[11] Ibid, pp. 37

[12] Ibid

[13] World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2013).

[14] Sinan, U. 2012. ‘Supporting Arab Economies in Transition’, Carnegie Endowment (5 July 2012).

[15] Keynes, J.M., 1926. The End of Laissez-Faire (London: Hogarth Press).