Series Introduction

Israel–Asia Relations: New Trends, Old Challenges?

Much of the scholarship on Israel’s foreign policy focuses on its relations with countries in the West or with its Arab neighbours; the significant rapprochement between Israel and countries in Asia has been largely neglected. There have been many indicators in the past decade pointing to these burgeoning ties – from China’s involvement in Israel’s infrastructure (in particular, Haifa port), the rise of Israel–India economic and security cooperation, and the expanding trade between Israel and Indonesia to the recent establishment of a new quadrilateral forum, the “I2U2”, comprising India, Israel, the United Arab Emirates and the United States.

Against the backdrop of these burgeoning relationships, the Middle East Institute at NUS convened a two–day workshop in February 2023 gathering together scholars from across the world – including Israel, China, the United States, Turkey, Indonesia, France and Singapore – to explore the depth of Israel’s partnerships across Asia. The seminar delved into the political and economic drivers of these relationships as well as their scope (and limitations). Particularly, it discussed the evolution of Israel’s policy towards China, India and Japan. It also looked into lesser known areas, such as Israel–Azerbaijan relations and the development of Holocaust studies in China. Altogether, the seminar shed light on a research topic – Israel’s Asia policy – that is likely to expand in the coming years. This is the first of the papers based on the seminar.

CLICK HERE FOR THE PDF

By Rotem Kowner*

Notwithstanding the flurry of bilateral visits, conclusion of several agreements and the flow of Japanese investments on an unprecedented scale to Israel in recent years, Israel-Japan relations remain largely confined to the economic sphere. The relationship is determined largely by the Japanese side, based on cold calculation of the assets and liabilities that it brings to Japan. Despite the recent change in the economic and geopolitical situation in the Middle East, Japanese policy is still aimed at finding a comfortable balance between the risks that relations with Israel entail in terms of Japan’s energy supply from the Gulf states and the political and economic advantages that the relationship may bring.

Israeli-Japanese relations began to improve substantially from the 2010s onwards, particularly since 2012, when the late Abe Shinzō’s second term as prime minister began. Under Abe’s eight-year long premiership, Japan implemented a more proactive foreign policy and forged new alliances,[1] fuelled by the premier’s vision of making Japan a great power (again) and growing concerns in Japan about a rising China threat and weakening American presence in Asia. Warming relations with Israel are a component of this new policy although other calculations intrinsic to the Middle East have also come into play and limit Japan’s interest in pursuing a radical change in the relationship.

The improvement in Israel-Japan relations can be seen in the frequent exchange of visits by high-ranking officials and the conclusion of several bilateral agreements. Moreover, during the past few years, Israel has become the target of Japanese investments of unprecedented scale. But does the takeoff during the recent decade indicate a true watershed in the 70-year history of lukewarm Israeli-Japanese relations? Moreover, can we expect Japan’s new strategic policy announced in December 2022[2] to herald a fundamental change in attitude towards Israel? Based on official documents, media sources and interviews with decision-makers, this paper seeks to analyse the current state of the relationship and the obstacles that stand in the way of deeper relations.

A Decade of Change: A Boost in Economic Ties and Beyond

Starting in 2012, the eight-year period under Prime Minister Abe was characterised by a considerable boost in Israel-Japan relations. Conspicuous in the economic sphere, this upturn seems to have endured following Abe’s departure from office in 2020 and well into 2022. There are several components to this shift, most of them the outcome of decisions and actions taken by the Japanese side.

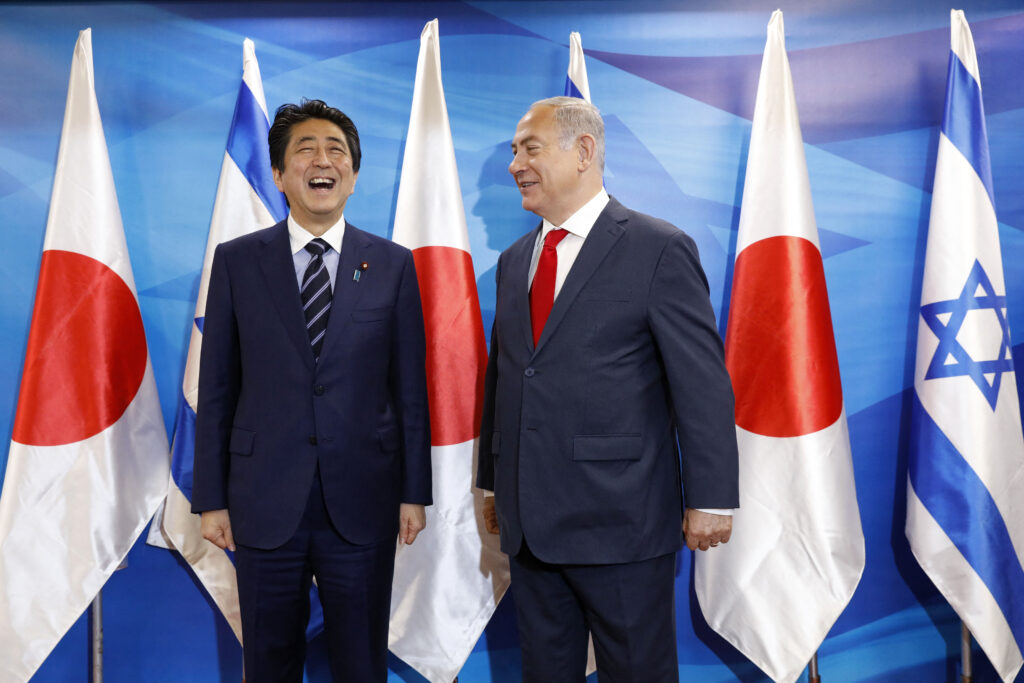

In terms of diplomatic exchanges, the decade of the 2010s was unprecedented, with two visits to Israel by Abe (in 2015 and 2018) and a visit to Japan by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (in 2014). The economic focus of the relationship was manifested in several visits by high-ranking representatives of Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI). METI ministers, who had never visited Israel before 2014, did so three times within the next five years.[3]

Trade and Investments

Investments, rather than trade, have been the most prominent aspect of the new atmosphere in the relationship during and since Abe’s second, third and fourth cabinets (2012–2020). The increase in Japanese investments in Israel and the increasing number of Japanese acquisitions of Israeli companies during this period were spectacular.

In 2021, Japanese investments, involving 85 deals, reached an all-time record of US$2.9 billion – a nearly 2,000 per cent jump from the US$142 million, involving just six deals, recorded in 2012, the year that Abe took office again after a brief tenure earlier.[4] Japanese investments declined in 2022 by almost half the figure for the previous year, but nonetheless constituted 12.8 per cent of total foreign investments in Israel that year.[5] Altogether, by 2022, total Japanese investments during the previous two decades reached about US$14.5 billion, the vast majority of them flowing since 2016.[6] Japanese investments in the Israeli high-tech industry have been increasing in recent years. Until a decade ago, these investments were relatively marginal, comprising no more than 1–2 per cent of all foreign investments in Israel’s high-tech sector. Since 2020, however, they have jumped to about 10–16 percent.[7]

Unlike investments, bilateral trade has remained sluggish on the whole. During much of the 2010s, Japan was only Israel’s third- or fourth-largest trade partner in Asia, after China and India, and at times even South Korea. Moreover, since 1997, Israel’s trade balance with Japan has been invariably negative, with the deficit reaching a peak of more than US$1 billion in 2007–2011 and in 2016–2018. The volume of Israeli exports to Japan in the early 2020s was lower than that in 1995–1997 (even in nominal terms). Content-wise, diamonds no longer constitute the main Israeli export as they used to three decades ago – a clear sign of the development and diversification of the Israeli economy.[8]

Despite the stagnation in bilateral trade during the 2010s, and even the decline seen during the last few years, there are some prospects for long-term change. In November 2022, the two countries launched a joint study on the possibility of a Japan-Israel Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA), namely, a scheme to create a free trade area. Negotiations are expected to take some two years.[9]

Security Ties

Another component of recent ties between Israel and Japan involves security. For decades, Japan shunned any sort of military ties with Israel, either the export or import of weaponry, let alone any joint military training or operational cooperation. Although Japan faces the serious threat of a ballistic missile attack by North Korea, it has shown no interest in acquiring Israel’s advanced air-defence systems or in collaborating with Israel on any of its weapons development programmes.[10] This disinterest may have been due in part to real or anticipated pressure from Washington to stick to American weapons systems.

Whatever the reason, in recent years, Japan has budged slightly from its reluctance to purchase Israel’s military and security technology. This is notable in non-lethal domains such as cybersecurity, a domain where Japan believes Israel’s advanced technologies could contribute to enhanced security. In May 2014, the two governments agreed to establish a dialogue on cybersecurity, and, half a year later, the first discussions were held.[11] Three years later, the two countries signed a cybersecurity cooperation agreement, and in October 2018 they held their first politico-military dialogue. In September 2019, the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding to strengthen their defence cooperation. By 2021 Japanese companies had made no less than 106 deals with Israeli cybersecurity companies, including the acquisition of some and investment in others.

People-to-People Ties

Travel, the most salient aspect of people-to-people ties, had steadily increased between the two countries during the 2010s and until the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in early 2020.[12] Starting with about 20,000 Japanese and Israeli visitors in 2011, the number of visitors travelling between the two countries more than tripled to 66,000 visitors in 2019. The lack of direct flights connecting the two countries has been a major impediment to the growth of travel between the two countries but this may change in the near future if the Israeli national carrier goes ahead with its plan to start direct flights to Japan, which had stalled following the onset of the pandemic.[13] Nonetheless, the constant warnings against travelling to Israel by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs are probably a more compelling factor in the relative paucity of Japanese visitors to Israel. Although the size of the Japanese population is more than 10 times that of the Israeli population on a per capita basis, the number of Israeli visitors to Japan was more than 20 times greater than the number of Japanese visitors to Israel. Moreover, since nearly 90 per cent of Israeli visitors to Japan were (non-business) tourists, compared with only 50 per cent among Japanese visitors, the gap in the number of tourists is even greater.[14]

Factors Behind the Change

The main reason behind the upswing in Israeli-Japanese relations is the changing position of Israel in the Middle East. Since the outbreak in 2011 of widespread protests and uprisings known as the “Arab Spring”, the Middle East has witnessed major fissures. These have led to a further weakening of some of the countries in the region that were most staunchly opposed to Israel, which, in turn, has diminished their support for the Palestinian cause. The most notable of these countries is Syria, which has suffered a devastating civil war since 2011. A sworn enemy of Israel in the past, Syria was divided territorially, millions of its citizens became refugees and the central government lost a great deal of its military might.[15] Iraq, for its part, has not recovered fully from the conflict that followed the invasion by the US-led coalition in 2003. Following a long and eventually successful struggle against the forces of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (popularly known as ISIS) that rose in the country, Iraq has experienced ongoing civil unrest. Likewise, Libya has experienced a revolution during which Muammar Gaddafi, its long-time leader and one of Israel’s most hostile opponents, was killed in 2011.

Japan has followed closely the ensuing decline in Arab disunity and has been concerned with the civil deterioration in the region, especially as some of its repercussions touched it directly. In 2015, for example, ISIS militants executed two Japanese hostages in Syria, in an act that received wide public attention in Japan. The execution, which was carried out despite the Japanese government’s reported willingness to pay a huge ransom for the hostages’ release, shocked the public and forged an essential consensus in the country on the need to fight Islamist terrorism.[16]

Against this backdrop of growing Arab disunity and weakness, and partly because of it, Israel has turned into a regional bastion of stability and military might. Moreover, over the past three decades, Israel has witnessed considerable demographic growth and impressive economic expansion. Its high-tech sector has burgeoned and its military capabilities have grown in size and sophistication, outperforming potential rivals. Steady American support, especially during the tenure of President Donald Trump (2017–2021), made its position even stronger. In 2020, Israel was able to improve its ties with several Arab countries – Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Sudan and Morocco – and consequently six members of the Arab League now recognise it. Even Saudi Arabia, the region’s largest oil producer and a leading Arab state, has recently recognised Israel as a “potential ally, with many interests that we can pursue together” and allowed Israeli airlines to fly through its air space.[17]

Nevertheless, the Arab position towards Israel is not the only local factor determining Japanese policy towards the Middle East. Iran, which holds the world’s second largest natural gas reserves and the fourth largest proven crude oil reserves, has been far more crucial for the Japanese economy than Israel. Until 2008, when the value of Japanese imports from Iran was over US$17 billion, consisting largely of crude oil, and even as late as in 2011, when total oil imports from Iran exceeded US$12 billion, relations with Israel could risk this important source of energy.[18] Subsequently, however, Washington has forced Tokyo to bow to the nuclear-related international sanctions against Iran.[19] As a result, by 2015, overall Japanese imports from Iran amounted to little more than US$3 billion and total bilateral trade was about US$3.6 billion. A year later, Japanese imports of crude oil from Iran declined even further, alongside a similar decline in the total value of imports of Middle Eastern oil to 47.8 and 39.5 per cent of its levels in 2011 and 2013, respectively.[20]

The final factor in Japan’s policy is the stronger position that China has gained in the Middle East over the past decade. Tokyo is particularly wary about the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – Beijing’s most important geopolitical project in Asia and beyond. Although the Japanese opposition to the initiative has relaxed considerably in recent years, Japan still regards the BRI, in Yoram Evron’s words, “as a threat to its decades-long effort to spread its influence over Asia through infrastructure development projects across the continent.”[21] The Sino-Japanese rivalry has turned into intense competition in a few Middle Eastern countries, as can be seen in Japanese investments in Chabahar. This Iranian port is located only 72 kilometres from the port of Gwadar in Pakistan, which was built by China as part of the BRI.[22] In Israel, by contrast, Japan has not endeavoured to compete with China’s large investments in infrastructure (ports, roads, etc.), but its recent government-induced investments in Israel’s high-tech companies and startups seem, in part, to be an attempt to keep its grip in Israel.

Preliminary Conclusions

On the whole, it is the changing geopolitical situation in East Asia and the Middle East that is at the root of the shift in Japan’s policy towards Israel during the 2010s. Under Abe’s long premiership, Japan implemented a more proactive foreign policy and forged new alliances.[23] Warming relations with Israel were essentially a component of this new policy. The outcomes of this policy – which is driven by Abe’s vision of making Japan a great power (again), in addition to concerns about a rising Chinese threat and weakening American presence in Asia – are still debatable. There is little doubt, however, that even though Abe was unable to accomplish his plan of revising Japan’s pacifist constitution, Japan has become slightly more independent diplomatically in recent years.[24] This does not mean that Abe and his immediate successors wished to pursue a radical change in Japan’s Middle East policy and its policy towards Israel in particular. To start with, they do not have a compelling reason to do so. Whereas the relationship with Israel is no longer a major liability, it is still far from an evident asset as Israel does not hold any trump card that Japan covets in particular. Secondly, Japan under Abe and his successors has remained under the US security umbrella. Indeed, whether it has remained a “reluctant” realist state actor, as some argue, or is resentfully supporting the existing US-led international security order, Japan has not changed dramatically its fundamental conceptions of world affairs. Crucially, it is still unwilling, perhaps also unable, to make a truly radical move towards an independent foreign and security policy.[25]

*Rotem Kowner is a Professor of Japanese Studies at the University of Haifa, Israel. He is the co-founder of the Israeli Association of Japanese Studies and served as its chair. His current scholarly interests include Japanese wartime behaviour, race and racism in East Asia, and Israel’s foreign policy in Asia.

Image caption: Then Prime Minister Shinzō Abe of Japan and his Israeli counterpart, Benjamin Netanyahu, posing before the media during the former’s visit to Jerusalem, 2 May 2018. Photo: Abir Sultan/AFP.

End Notes

[1] See Andrew Oros, Japan’s Security Renaissance: New Policies and Politics for the Twenty-First-Century (Columbia University Press, 2017).

[2] Cabinet Secretariat, Japan, “National Security Strategy of Japan”, December 2022, https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/siryou/221216anzenhoshou/nss-e.pdf

[3] The visits were undertaken in 2014, 2017 and 2019.

[4] Meir Orbach, “Si behashka’ot yapaniyot behavarot Israeliyot be-2021” (Record of Japanese Investments in Israeli Companies). Calcalist, 9 January 2022

[5] Harel-Hertz Investment House, “Press Release: Japanese Investments in Israel in 2022 Amounted to $1.558 Billion”, 9 February 2023.

[6] Based on Harel-Hertz Investment House, Japan Year Book (Herzliya: Harel-Hertz, 2022), p. 2, https://www.harel-hertz.com/israel-japan

[7] Based on Harel-Hertz Investment House, Japan Year Book, p. 25; Hidemitsu Kibe, 2016. “Japanese Companies Show Keen Interest in Israeli Startups”, Nikkei Asia, 6 December 2016.

[8] Israel Export Institute, “Israel-Japan Economic Survey”, 2019, https://www.export.gov.il/api//Media/Default/Files/Economy/japanisraelcomrel18.pdf.

[9] Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Foreign Minister Hayashi Attends Reception in Celebration of the 70th Anniversary of the Diplomatic Relations between Japan and Israel”, 22 November 2022, https://www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/press3e_000505.html; Israel Fisher, “Mazda veToyota yihiyu zolot yoter” (Mazda and Toyota Will Be Cheaper?) TheMarker, 22 November 2022, https://www-themarker-com.ezproxy.haifa.ac.il/dynamo/2022-11-22/ty-article/.premium/00000184-9f36-da0b-a985-ff7ffb240000. As of 2022, Israel has signed economic partnership agreements with 47 states; among them only two are in Asia: South Korea (2021) and the United Arab Emirates (2022).

[10] That said, Japan in the past did purchase some Israeli-made electronic components that could be used in weapon systems. See Udi Etzion, “Hataa’siyot habithoniyot rotsot lihiyot gdolot beYapan” (The Defense Industries Wish to Become Big in Japan), Calcalist, 26 November 2019, https://www.calcalist.co.il/local/articles/0,7340,L-3774514,00.html.

[11] Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Japan-Israel Relations: First Dialogue on Cyber issues between Japan and Israel”, 18 November 2014, https://www.mofa.go.jp/me_a/me1/il/page22e_000617.html.

[12] By the summer 2022, some 30 months after the outbreak of the pandemic, bilateral tourism had still not resumed.

[13] The Israeli flag carrier El Al intended to launch direct flights to Japan in March 2020 but due to the pandemic the launch was postponed. Starting in March 2023, and due in part to the recent Saudi decision to open its airspace to all aircraft flying to and from Israel, El Al will renew its plan for direct flights. See Zachy Hennessey, “Israel’s El Al to Offer Direct Flights to Tokyo and Melbourne”, The Jerusalem Post, 27 July 2022, https://www.jpost.com/business-and-innovation/all-news/article-713214.

[14] An internal report of the Embassy of Israel, Tokyo, whose contents the author had access to through official sources.

[15] For the Japanese reaction to the Syrian Crisis, see Srabani Roy Choudhury, “Japan and the Middle East: An Overview”, Contemporary Review of the Middle East 5, no. 3 (2018): 191–2.

[16] John Gambrell and Mari Yamaguchi, “Japan Weighs Ransom in Islamic State Threat to Kill Hostages”, Associated Press, 20 January 2015P; BBC, “Japan Outraged at IS ‘Beheading’ of Hostage Kenji Goto”, BBC, 1 February 2015.

[17] France24, “Do Signs Point to an Israel-Saudi Normalisation Deal?” France24, 26 June 2022, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20220626-do-signs-point-to-an-israel-saudi-normalisation-deal.

[18] Mari Nukii, “Japan-Iran Relations since the 2015 Iran Nuclear Deal”, Contemporary Review of the Middle East 5, no. 3 (2018): 221 (Table 1).

[19] For Japan’s wavering under American pressure on the Iranian nuclear issue and investments in oil infrastructure, see Yukiko Miyagi, “Japan’s Middle East Policy”, International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 12, no. 2 (2012): 306–8; Choudhury, “Japan and the Middle East”, 190–1.

[20] For Japan’s declining crude oil import from Iran, alongside other Middle East oil producers, during 2011–2016, see Choudhury, “Japan and the Middle East”, 193 (Table 1).

[21] Yoram Evron, “Implications of China’s Belt and Road Initiative for Japan’s Involvement in the Middle East”, Contemporary Review of the Middle East 5, no. 3 (2018): 200, 207; Yoram Evron, “China–Japan Interaction in the Middle East: A Battleground of Japan’s Remilitarization”, The Pacific Review 30, no. 2 (2017): 188–204. For the Japanese view of China and the strategy to contain it during the 2010s, see Michael J. Green, 2022. Line of Advantage: Japan’s Grand Strategy in the Era of Abe Shinzō (Columbia University Press, 2022).

[22] Nukii. “Japan-Iran Relations”, 223–5.

[23] See Andrew Oros, Japan’s Security Renaissance: New Policies and Politics for the Twenty-First-Century (Columbia University Press, 2017).

[24] For this revision, see Jeremy A. Yellen, “Shinzo Abe’s Constitutional Ambitions”, The Diplomat, 12 June 2014, http://thediplomat.com/2014/06/shinzo-abes-constitutional-ambitions/

[25] See, for example, Giulio Pugliese and Alessio Patalano, “Diplomatic and Security Practice under Abe Shinzō: The Case for Realpolitik Japan”, Australian Journal of International Affairs 74, no. 6 (2020): 615–32.