- 01 Apr 2021

The Gulf and Beyond: Assessing Israel’s Expanding Arab Relations

(This event is organised by MEI’s Gulf Research Cluster)

Abstract

In the last six months, a flurry of Arab states, including the UAE, Bahrain, Sudan and Morocco, established diplomatic relations with Israel or announced their intention to do so. The “honeymoon period” for Israel, the UAE, and Bahrain is coming to an end. Sudan and Morocco have yet to finalise details of their recognition of the Jewish state. Israeli and Emiratis basked in the warmth of the receptions that they received in each other’s countries and the prospects of a blossoming security, commercial and trade relationship.

Yet, despite a series of business deals and cooperation agreements in areas such as aviation, technology, agriculture and education, not all went according to expectations. Israel suspended the purchase of one of its most storied and controversial football clubs because of questions about the solvency of the Emirati buyer. An Israeli alliance of high-powered security and technology companies lost a bid for an Emirati cybersecurity center and Israeli Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu cancelled visits to the UAE and Bahrain. In this webinar, a panel of prominent experts will assess the current state of affairs, as well as the prospects of more states – not limited to the Gulf region – in recognising the Jewish state.

This public talk will be conducted online via Zoom on Thursday, 1 April 2021 from 4.00pm to 5.30pm (SGT). All are welcome to participate. This event is free, however, registration is compulsory. Successful registrants will receive a confirmation email with the Zoom details closer to the date of the event.

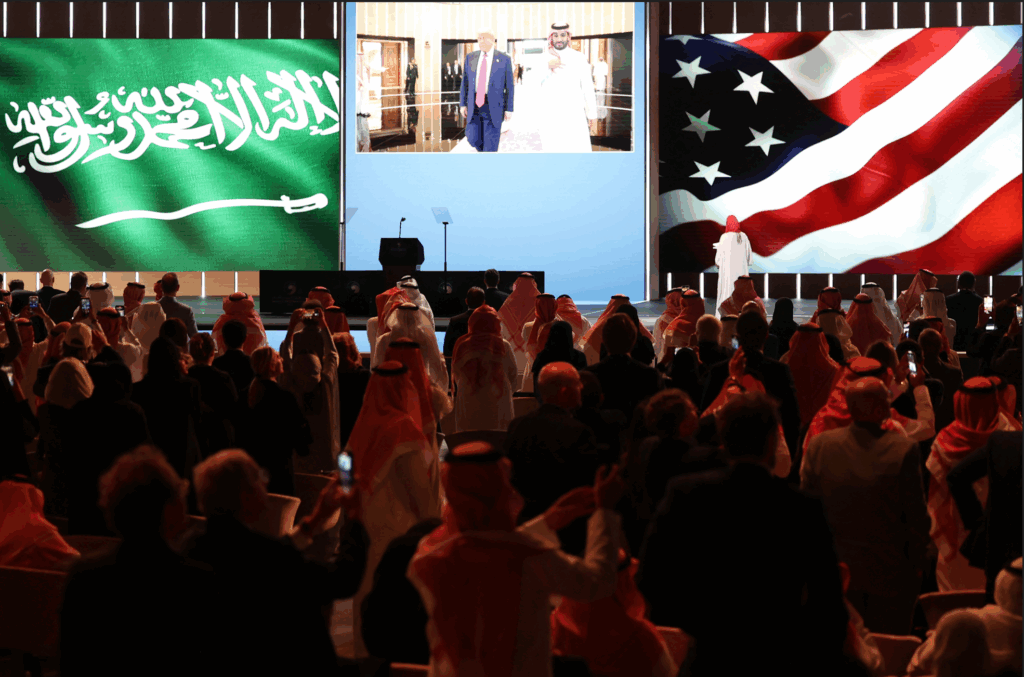

Image caption: Israeli and United Arab Emirates flags line a road in the Israeli coastal city of Netanya, on August 16, 2020. (Photo by JACK GUEZ / AFP)

Listen to the full event here:

Watch the full event here:

Read the Summary of Event Proceedings:

By Tan Feng Qin

Research Associate, Middle East Institute, National University of Singapore

Yossi Melman, an Israeli journalist and writer, Ali Dogan, a research fellow at Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient in Berlin and Yoel Guzansky, senior research fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies at Tel Aviv University discussed issues around Israel’s diplomatic normalisation efforts in the Arab world, also known as the Abraham Accords and examined what lay ahead for Israel’s relations with the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

Israeli Domestic Politics and the Future Trajectory of Normalisation

Mr Melman began by giving an overview of Israel’s recent elections and its relation to the normalisation efforts. The Israeli elections were inconclusive, with the country once again facing a political deadlock and a slim chance that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu will be unable to form a governing coalition. The results were a reflection of divisions, falling along religious, ethnic, demographic and ideological lines within a polarised society rooted in 40 years of Israeli politics.

The elections revolved around Mr Netanyahu and his continued premiership. At this point it is not yet clear if Mr Netanyahu will be removed from office but Mr Melman noted that the prime minister is a great political player who should never be counted out. The elections did not revolve around foreign policy issues or achievements, including the diplomatic normalisation accords and the results are not likely to affect Israel’s foreign policy, except at the margins, regardless of who forms the next government.

Israel has been building relations with the Arab world for the last four decades. Mr Melman identified four developments that facilitated the Abraham Accords.

First, an increasing number of Arab nations, together with the Arab masses, had become fatigued with the stalemate around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Second, some Arab nations, including the UAE, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Oman, had already developed security and intelligence ties and unofficial relations with Israel over a shared concern about Iran. Third was the opportunity for co-operation with Israel in the areas of cybertechnology, innovation and other fields, and last was the decision of former US President Donald Trump to break-away from prevailing US Middle East policy, which had, since 1967, acceded to the view that Arab relations with Israel could not move forward unless progress was made on resolving the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

However, Mr Melman warned that the Palestinian issue could ultimately still hinder diplomatic normalisation. The case of Saudi Arabia exemplifies the concern. Saudi Arabia has not normalised relations with Israel, and is unlikely to do so unless there is some progress on resolving the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Ties are unlikely to develop in the open as long as Saudi King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud remains in power, despite Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud’s willingness to move in big and bold ways.

Furthermore, relations between Israel and the Arab world remain fragile. Many Arab states opened embassies and developed relations with Israel after the conclusion of the Oslo Accords in the 1990s. Mr Melman identified diplomatic missions by Morocco, Qatar, Mauritania, Oman and Bahrain. However, when the Second Intifada broke out in the 2000s, these relations were cut and diplomatic missions closed. Israel’s new public ties with some in the Arab world remain fragile and violent events, such as another Israeli military invasion of Gaza, could threaten these new ties.

Neom Diplomacy and the Future of Saudi–Israel Relations

Mr Ali Dogan next covered developments in the Saudi Neom project and how this could provide an opening for Saudi-Israel ties. Neom is a name that combines the term “neo,” or new, with the letter “m,” representing the Arabic word for future, mustaqbal (مستقبل). It is a US$500 billion dollar planned city project located in the northwest Tabuk region of Saudi Arabia bordering the Gulf of ʿAqaba, which also touches Israel and Egypt. Neom is part of the Saudi Vision 2030 project, which aims to prepare the country for a post-oil era by seeking to diversify its economy, following on earlier projects such as the King Abdullah Financial District and the King Abdullah Economic city.

Neom plays several roles in Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy, said Mr Dogan. First, Neom is used together with Saudi Arabia’s other development projects as a soft power tool that aims to reshape the image of Saudi Arabia, especially in the West, by focusing on the projects’ futuristic aspects, their tourism potential and the liberal ideas the projects are thought to embody. Advertisements in the Wall Street Journal, on European television channels and YouTube have sought to highlight these aspects.

Second, Neom itself has increasingly been directly used in Saudi foreign policy as a venue for diplomatic negotiations and high-level meetings, including the November 2020 meeting between Prime Minister Netanyahu, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Yossi Cohen, the director of Mossad, Israel’s external intelligence agency. Other meetings at Neom have included those between King Salman and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi in 2018 and between the Saudi crown prince and China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi in March 2021.

Mr Dogan further argued that the completion of Neom could require Saudi Arabia to develop ties with Israel. Egypt handed over the islands of Tiran and Sanafir to Saudi Arabia in 2017. The Neom project incorporates both islands and also includes a planned bridge to Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula across the Straits of Tiran, which opens northwards into the Gulf of ʿAqaba and the Israeli port of Eilat. As Israel’s access through the Straits of Tiran is provided for in the 1979 Egypt–Israel Treaty of Peace, it is Mr Dogan’s view that negotiations between Israel and Saudi Arabia will be required to complete the bridge.

At the same time, the Saudi crown prince’s ambitions to complete Neom are also likely to negatively impact Saudi–UAE relations. Dubai currently hosts the regional headquarters of many western companies. Saudi Arabia has begun to compete with the UAE on this issue, recently stating that companies who do not establish their regional headquarters in Saudi Arabia by 2024 will not be awarded Saudi state contracts. The Neom project could also see Saudi Arabia’s foreign relations change in other ways under the crown prince, with Mr Dogan noting Russian plans to invest several billion dollars in Neom.

Complicating Factors in the Future of Israel–Gulf Relations

Dr Yoel Guzansky closed the session with his assessment of the challenges facing Israel–Gulf relations despite the conclusion of the Abraham Accords. He first sought to clarify the nature of Israel–Gulf ties. One can better understand these ties by imagining two horizontal lines parallel to one another. The upper line represents public, open relations between Israel and the Gulf and the lower one represents a more strategic and tacit dimension of these relations.

Both lines may be affected in different ways by international developments, independent of each other. For instance, while the change in US administrations could potentially slow down Israel’s public normalisation with the UAE, tacit relations between Israel and the UAE might actually be strengthened as a result of mutual worries about Middle East policy in the new administration of US President Joe Biden. Public relations and tacit ties between Israel and the Gulf may develop at a different pace and sometimes also in opposite ways.

The normalisation of ties between Israel and the UAE has economic potential and could bolster Israeli deterrence of Iran. Israel’s strategic environment would also improve should Saudi Arabia follow in the UAE’s footsteps and normalise relations. As such, Israel–UAE normalisation has the potential to be a game-changer in the Middle East. However, this potential has not yet materialised.

Diplomatic normalisation with Israel has presented its own set of challenges for the UAE. By positioning Israel and the UAE together, the agreement exposes the latter to criticism, and even threats from Iran, while public ties could also limit aspects of security cooperation which are better kept in the shadows.

Differences in strategic priorities have also further limited overt security co-operation. The UAE has been de-escalating tensions with Iran in the past year and a half and does not intend to become Israel’s forward operating base against Iran. Neither does Israel intend to become the UAE’s forward operating base against Turkey. Saudi Arabia and the UAE can also be expected to stay quiet publicly on the Iran nuclear deal issue to preserve delicate relations with the US, though they are likely to continue co-ordinating tacitly with Israel on policy towards Iran and the US. While Israel is focused on the nuclear issue and Iran’s intervention in Syria, the Gulf Cooperation Council is more concerned about Iran’s ballistic missiles and the situation in Yemen. As a result of these differences, an overt security pact between the Gulf countries and Israel is unlikely, and tacit co-operation will likely continue instead.

The UAE and Israel also view the Abraham Accords differently, with the former focusing on the deal’s benefits, and the latter seeing the Accords as proof that Israel has been accepted in the Middle East. The Israel–UAE agreement is the most important of the Accords, as the agreements with Bahrain, Sudan and Morocco still lack substance and would not have gone forward without UAE and Saudi support and funding from the UAE. Furthermore, the Israel–UAE agreement would not have been implemented without massive pressure and significant incentives from the Trump administration, including the potential sale of US F-35 aircraft to the UAE. The agreement was also largely one between governments. While there has been a slight favourable shift in Gulf public opinion towards normalisation with Israel since the signing of the Accords, 70 to 80 per cent of Emiratis and Saudis remain opposed to a public normalisation with Israel. It is not clear if Israelis fully understand these facts.

To conclude, Dr Guzansky reiterated that UAE–Israel relations would never have gone public without US pressure and incentives. Although the Biden administration has supported the normalisation agreements in its statements, Dr Guzansky argues that US–Gulf relations have chilled, citing the re-examination of the F-35 deal by the new administration. These changed relations could slow the pace of Arab normalisation with Israel.

Highlights from the Question and Answer Session

When asked what strained relations between Israel and Jordan on the eve of the Israeli elections imply for wider Arab–Israeli relations, Mr Melman said that although Israel–Jordan relations have been slowly deteriorating in recent years, the two countries still need one another and retain mutual interests. Israel helps Jordan by providing intelligence on threats in Syria or Iraq and on the Islamic State group, and Jordan co-ordinates with Israel on Palestinian issues and provides a strategic buffer zone between Israel and the potential entry of foreign armed forces, denying Israel’s opponents a possible launching pad into the country. As such, Jordan will remain an ally of Israel.

Mr Melman added that while ties between Israel and the Arab nations are mainly between governments, as Dr Guzansky noted, Arab governments also have the potential to shape the perceptions of the Arab masses, including through education. It is Mr Melman’s view that the trajectory of relations since 1948 shows that the Arab world is accepting Israel as a fact of life, and as more Arab countries accept Israel, so will their masses.

One question was whether Neom’s geographical advantages could position the developing project favourably in the internal Saudi competition to entice companies to establish their regional headquarters there instead of in other already developed cities closer to Saudi Arabia’s existing economic zones. Mr Dogan’s response was that its location near Israel and its high-tech companies, the Suez Canal and the large Egyptian market could make Neom attractive to Western companies. He also noted that Saudi Arabia’s existing development projects, such as the King Abdullah Economic City, have suffered in competition with Dubai in the UAE. Mr Dogan felt Neom’s location, together with Saudi efforts at cultural liberalisation as well as a continued development of the project itself could attract Western companies into Saudi Arabia in the future.

On the question of de-escalation of tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran, Dr Guzansky was of the view that Israel should be concerned about potential dialogue between Iran and the Gulf states, including Saudi Arabia. It is in Israel’s interests to form a united bloc of Arab, Sunni monarchies against Iran, said Dr Guzansky. Israel and the Trump administration worked hard to form such a bloc, but it is crumbling. He said that Saudi Arabia’s stance on Iranian pilgrims for the upcoming haj could be a good indicator of future Saudi–Iran ties and the issue could also lead to further dialogue between the two countries. Furthermore, the UAE has been trying to improve relations and de-escalate tensions with Iran, and Dr Guzansky noted that Saudi Arabia sometimes follows the UAE’s lead on Iran. With the failure of both the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen and the boycott of Qatar indicating the limits of Saudi power, it is possible that the need to improve ties with the new Biden administration could see Saudi Arabia reach out to Iran as a political gesture to the White House.

About the Speakers

Journalist

Security and Intelligence Commentator

Mr Ali Dogan

Research Fellow

Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO), Berlin

Dr Yoel Guzansky

Senior Research Fellow

Institute for National Security Studies

Tel Aviv University

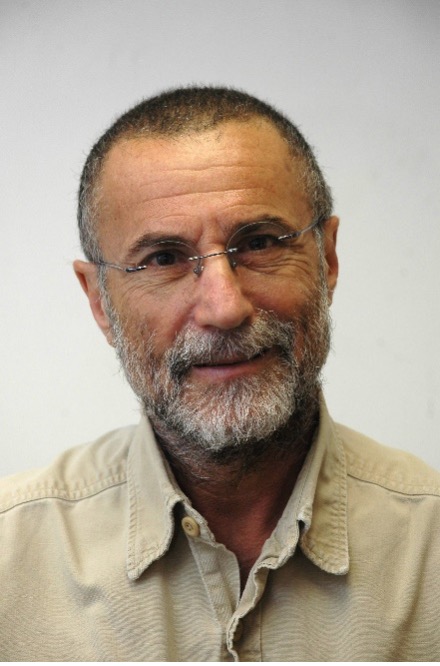

Mr Yossi Melman is an Israeli journalist, commentator and writer specialising in strategic, security, intelligence and nuclear affairs. He covers these topics for the Israeli daily Haaretz and contributes to numerous publications around the world. He is the author of ten books on Israeli and Middle Eastern security including the New York Times bestseller “Every Spy A Prince and Spies Against Armageddon”, co-authored by Dan Raviv, a former CBS writer. In 2017, Mr Melman created the Netflix documentary series “Inside the Mossad”. He graduated from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and won several international awards including the Sokolov Award, Israel’s most prestigious media award.

Mr Ali Dogan is a Research Fellow and doctoral candidate at the ZMO and is doing his doctorate on the cooperation between the Federal Intelligence Service and the Iraqi intelligence services from 1969-1990 at the Otto Suhr Institute (FU Berlin). Before that, he worked as a consultant for the German Business Delegation for Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Yemen (AHK). In his role, he advised the DIHK, BMWi and various business delegations and took part in regional conferences. He completed his BA in studies of the Near and Middle East (LMU Munich), his first MA in the “German and Turkish Masters Program in Social Sciences” (METU Ankara, HU Berlin – funded by the AA and DAAD) and his second MA in Peace and Security Policy (IFSH, University of Hamburg).

Dr Yoel Guzansky is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), Tel Aviv University, specialising in Gulf politics and security. Dr Guzansky is also a Non-Resident Scholar at the Middle East Institute. Dr Guzansky was a Visiting Fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, an Israel Institute Postdoctoral Fellow, and a Fulbright Scholar. He served on Israel’s National Security Council in the Prime Minister’s Office, coordinating the work on Iran and the Gulf under four National Security Advisers and three Prime Ministers. He is currently a consultant to several ministries.

[Moderator] Clemens focuses on the history and politics of the Gulf states, with a particular emphasis on Kuwait and Oman. His book project, entitled Kuwait’s Organising Agent, The Diwaniyya, studies the impact of the diwaniyyas (diwawin), places of social gathering for Kuwaiti men. He unveils how these unassuming reception rooms have implications for society, politics and diplomacy. Prior to joining MEI, he was the Al-Sabah Fellow at the School of Government and International Affairs, Durham University, UK.

Clemens obtained his PhD in Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies from Durham University, where he also received an MSc in Defence, Development and Diplomacy. He is also a Sciences Po Paris alumnus, having read his BA at the Menton campus.