- 02 Oct 2020

Israel’s Relationship with the Arab World

Abstract

More than a quarter-century of fitful, failed and abandoned attempts to resolve the Israeli–Palestinian conflict blocked efforts to formally widen the circle of Arab–Israeli peace after the Jordanian–Israeli treaty of 1994 — although under-the-table contacts and cooperation, mutually beneficial to Israel and key Arab states, were maintained. Shifting US policies, shared concerns about common enemies and recognition of potential opportunities created a different dynamic in recent years, culminating in the 13 August announcement of UAE–Israel normalisation. We’ll look at the long road to that milestone agreement and what might lie beyond it.

This public talk will be conducted online via Zoom on 2 October (Friday), from 9.00am to 10.30am (SGT). All are welcome to participate. An e-invite will be sent to you closer to the event date.

This event is free, however, registration is compulsory.

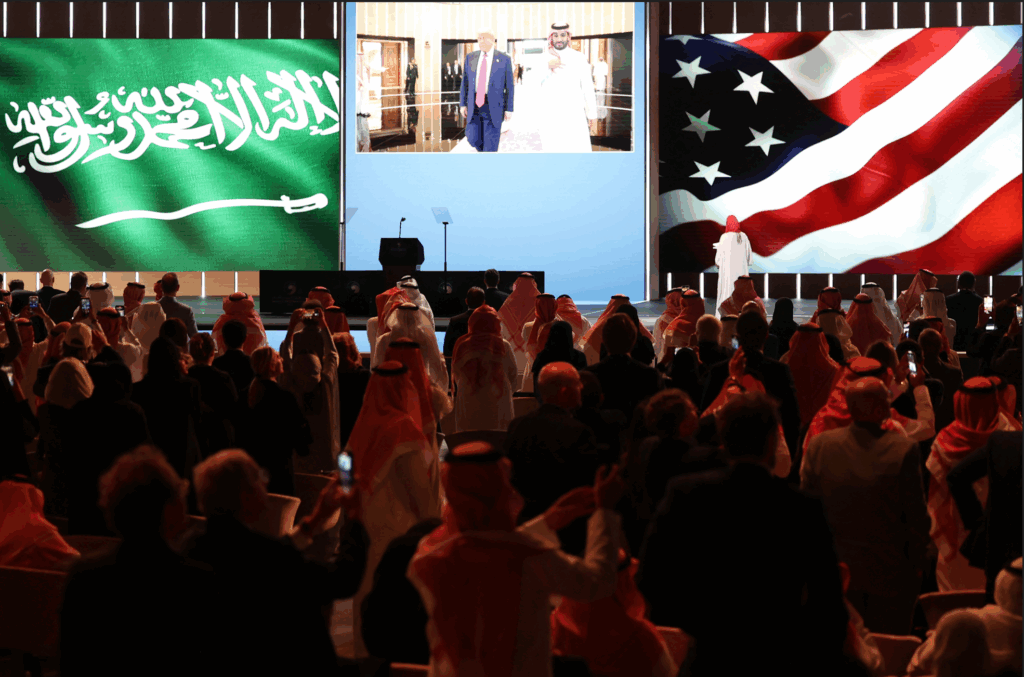

Image caption: Israeli and United Arab Emirates flags line a road in the Israeli coastal city of Netanya, on August 16, 2020. Jack Guez / AFP

Listen to the full event here:

Watch the full event here:

Read the Summary of Event Proceedings:

by Fadhil Yunus Alsagoff

Research Assistant, Middle East Institute, National University of Singapore

In his talk, Mr Jason Isaacson, chief policy and political affairs officer for the Global Jewish Advocacy (AJC), gave a succinct historical overview of Israel’s relationship with the Arab world. He also gave his analysis of the current state of this relationship and his thoughts on its future trajectories.

Mr Isaacson began his talk on Israel’s relationship with the Arab world with their early history in the mid 20th century. During this period, Israel’s relationship with the Arab world was in a miserable state, with decades of conflict, animosity and mistrust. He brought up the numerous coordinated efforts by the Arab world to criticise Israel through making resolutions against the country in multilateral forums. This was a time of many wars between Israel and the Arab states, including the independence war of 1948 and 1949, the Suez canal crisis in 1956, the Six-Day war of 1967, and the October war of 1973.

Change in this poor state of affairs had its humble beginnings in the late 20th century: with the fall of the Berlin wall, the collapse of Soviet Union, and the first Gulf War, the US emerged as a unifying force and the sole global superpower. Its administration brought together as many Arab states, including the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), in Madrid in October 1991 for the Madrid Peace Conference, the first real effort towards peace after the Camp David Accords and the Egyptian–Israeli peace treaty in 1979. Mr Isaacson, having then only recently joined the AJC, was present during this conference.

The conference charted the way forward for Israel and its neighbours to begin discussing the possibility of a relationship between Israel and the PLO. A few months later in January 1992, the second phase of Middle East peace-making was launched. It was a multilateral process that created several working groups to focus on key issues — such as water resources, arms control, and environmental issues — that could be addressed by policy experts and diplomats to try to reach some form of understanding and build trust in the region.

Out of that hopeful start in the early 1990s came a period of probing and testing at possibilities and convening in conferences to discuss those issues. Israelis were meeting with Arabs, not necessarily to solve the Israel–Palestine issue directly, but to focus on regional issues in general. In 1994, an AJC delegation went to Saudi Arabia for some discussions, in 1995, another went to Bahrain, Oman and Qatar. Through such efforts, four Arab states, namely Oman, Qatar, Morocco and Tunisia, reached what Mr Isaacson called low level relationships with Israel, which involved establishing interest offices or trade offices. In addition to non-governmental organisations, there were governmental discussions taking place. This included the landmark Oslo Accords of 1993, and the Jordanian–Israeli peace talks, which came to an agreement in 1994. In total, then, Israel had two full relationships (one with Egypt, one with Jordan) and four low level relationships with Arab states.

It was also during that hopeful period that AJC attempted to build bridges, establish further contacts and widen its network in order to break misconceptions Arabs had about Jews and to encourage amiable relations between them.

However, with the outbreak of the second intifada in October 2000, after a failed Camp David Summit in July the same year, hopes that Israel and Palestine would make peace soon were dashed. It became clear, said Mr Isaacson, that Yasser Arafat was not satisfied with the agreement required under the Camp David Accords, namely that only 92–94 per cent of the West Bank and a part of Jerusalem would be under Palestinian sovereignty. With the failure of the talks and the outbreak of the second intifada, the four Arab states that thus far had established low level relations with Israel cut ties with country.

Since then till quite recently, there were no formal relationships of any kind that existed between Israel and Arab states, with the exception of Egypt and Jordan. Mr Isaacson also mentioned the partial exception of Oman, whose sultan volunteered to take on the chairman position of the water resources working group. As the chair of the multilateral working group on water, Oman hosted something called the Middle East Desalination Research Center, where researchers and bureaucrats from a number of states — including Israel, Jordan, Japan, Korea and some European countries — would conduct research on desalination and water management technology.

It took years to encourage and facilitate contact between Israel and the Arab states. In his capacity as the director of governmental and international affairs at the AJC, and as a regular visitor to these countries, Mr Isaacson recalled expanding much effort to encourage those contact. He introduced people to one another, through email or the phone, and set up meetings in New York or in Europe between local officials. The American embassies in these countries did what they could to push such efforts forward. He also mentioned that secretive meetings took place in hotel rooms between Israeli and Arab diplomats from countries that did not recognise the state of Israel. Such meetings were kept under wraps and were of limited utility. Apart from these, there were the occasional statements made by a few Arab diplomats to try to encourage improving relations between Arabs and Israelis. Sheikh Khalid bin Ahmed Al-Khalifa, the foreign minister of the kingdom of Bahrain, for example, made a statement at the UN General Assembly about how Israel was a part of the region and that it should be included rather than isolated. Ultimately, however, all these efforts did not result in anything concrete.

This state of affairs started to change in 2016 when Israel reached a US$10 billion agreement to sell natural gas to Jordan. The details of the agreement were kept quiet for around three years because of the intense anti-Israel sentiment in Jordan. At this juncture, Mr Isaacson inserted that despite having signed their peace agreement, the level of contact between Israelis and Jordanians was appallingly low. There was government-to-government contact for their very important security cooperation. But business contact was almost non-existent, and there were fierce anti-normalisation efforts in Jordan, at the grassroots and parliamentary levels. In fact, when the deal became public, it was fiercely opposed in the Jordanian parliament and remained hugely controversial for several years.

Then in 2018, both Egypt and Israel agreed to a very substantial US$15 billion natural gas deal. This was also controversial in Egypt, though not to the same degree as it was in Jordan. In October the same year, then Sultan of Oman Qaboos bin Said invited Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his wife to Muscat. As the sultan was held in high esteem, the meeting did not cause the same reaction it would have had in other Arab states.

Two days after Mr Netanyahu left Muscat, Omani Minister of Foreign Affairs Yusuf bin Alawi, speaking at the Manama dialogue in Bahrain, spoke openly about the visit Mr Netanyahu had just made. Answering a question posed by Mr Isaacson, he spoke about Israel as being a state in the region that should have the same rights and obligations as any other state in the region. He also mentioned that it had been a mistake for the Arab world to isolate Israel and that it resulted in a lot of missed opportunities. During this same period, two Israeli ministers visited the United Arab Emirates (UAE), one to observe a Judo competition in which an Israeli athlete won in his category. The Israeli national anthem was played in the stadium in the UAE, and a minister presented the gold medal to this athlete. The other Israeli minster attended a telecom conference on cybersecurity.

In 2019, he said we witnessed the Peace to Prosperity Conference, convened in Bahrain by the Trump administration and Jared Kushner team who wanted to break the stalemate in Israeli–Palestinian peace process. This was intended to be done through two parallel tracks, one financial, the other political. The financial package was to be rolled out before the political package to induce the Palestinians to return to the political process by showing them what benefits they and the region could gain from doing so. Mr Isaacson said that the Palestinian leaders boycotted the conference and made it clear that they were unhappy with anyone else attending it. Regardless, other countries still chose to attend. Mr Isaacson said it was very significant to have Emirati, Bahraini and other officials from the region, along with American and European diplomats and International Monetary Fund representatives, coming together to discuss a future in which all the agreeing states would contribute to Israeli–Palestinian peace process and benefit from their own individual relationships with Israel as well.

Mr Isaacson then brought his listeners to the end of last year and the beginning of this year. On 28 January 2020, US President Donald Trump, with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu by his side, laid out the political aspect of the Peace to Prosperity vision that they had been preparing. It offered a shrunken future Palestinian state, where every current Israeli settlement, even the very remote ones deep in Palestinian territory, were connected by roads, bridges and tunnel to the main Israeli state. It was going to be a very complicated, multibillion dollar infrastructure project. The strange map that was put forward would include some 30 per cent of the West Bank, including the Jordan river valley, being brought under Israeli sovereignty and therefore taken out of the negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians for a future Palestinian state.

Palestinians obviously rejected that part of the plan, but several others Arab officials — mainly from Bahrain, Oman and the UAE — partly due to wanting to stay on the side of the US and partly due to their frustration with the Palestinian leadership — spoke positively about moving forward with the peace plan. They did not exactly agree to the American plan, but were willing to give it time to be studied and, perhaps, use it as a basis for negotiations.

Mr Isaacson said that it was that plan and the Trump administration’s promise to recognise Israel’s sovereignty over the annexed West Bank land that provided the key that could unlock the stalemate. He reasoned that it was Mr Trump’s threat to cripple the possibility of moving forward in any logical and smooth way toward Israeli–Palestinian peace that pushed His Excellency Yousef Al Otaiba, the UAE ambassador to Washington, to make an offer to Israel, which he did in June 2020. In an op-ed that he wrote, he said that the UAE was ready to move forward to make peace with Israel, but this application of Israeli sovereignty involving the annexation of Palestinian land would make it impossible. This was ultimately the deal that resulted in the announcement of 13 August, when Mr Trump, Crown Prince Muhammad bin Zayed of the UAE and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced that they were moving towards full diplomatic relations. It was just a few weeks later on 11 September that the announcement of Bahrain establishing full relations with Israel was made.

Gone were the days of quiet, secretive contact and deals, said Mr Isaacson. That is now all in the past, and the past is receding quite swiftly. Two days after the announcement on 13 August, an agreement was reached between two Israeli firms and an Emirati firm to cooperate against the Covid-19 pandemic; an Israeli soccer player is going to be joining a team in the Emirates; and there has already been one direct flight from Tel Aviv to Abu Dhabi. But Mr Isaacson said that there will be much more in the coming days and weeks, such as agreements on commercial aviation and the fast processing of visas.

On the possibility of a Palestinian–Israeli peace deal, Mr Isaacson reiterated that reaching out to Israel would have helped the Palestinian cause — isolating Israel did nothing to help the Palestinians. The whole premise since the Oslo Accords was to solve the Israel–Palestine conflict before engaging with Israel. To satisfy the Palestinians, this would involve a return to the 1967 lines, making East Jerusalem its capital, the safe return of refugees — all of which are decreasingly possible with each passing year, and now, he said, totally beyond reach. That was the condition, and until that happened, no Arab state would engage Israel.

But by flipping it around and engaging Israel first, instead of isolating it, the level of mistrust that Israelis have for their neighbours would be lowered. It would encourage compromise. Mr Isaacson said he believes that this message finally took hold among some Arab leaders, which is why we are now hearing from some Arab leaders that they would like to use their newfound position in establishing relations with Israel to help move Israelis in a direction that would more easily accommodate peace with the Palestinians.

Mr. Isaacson also hoped that the Palestinians would take this approach, as opposed to one of continual rejection and criticism of Arab states doing so. However, as of now, he does not see them to be accommodating themselves to this new reality, where their prospects of getting everything they want are shrinking by the moment. He further asserted that their prospect of getting something even reasonable is difficult and it really is time for the Palestinians to return to the bargaining table.

Looking ahead, Mr Isaacson said the sultan of Oman would probably move in a direction similar to the UAE and Bahrain after a while, as there has already been a history of Israeli–Omani contact. As for Sudan, he is of the opinion that there are real possibilities. Though some in the sovereignty council governing Sudan are not keen, the prime minster of Sudan himself seems committed to do so, as he expressed earlier in September. Mr Isaacson believes that Sudan recognises the benefits of having a relationship with Israel, which probably includes being removed from the US list of state sponsors of terrorism. He doubts that Tunisia would jump on the bandwagon any time soon, though he does see the Saudis doing so, though only after King Salman passes the throne to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Mr Isaacson also hopes that these development would bring a future of wider peace between Israel and the Arab world, and that this, in turn, would lead to a resolution between Israel and Palestine. Again, he reiterated that it is not the Israel–Palestine conflict that should be resolved before developing wider Arab ties with Israel. Rather, the conflict would be resolved as a result and in coordination with improvements in wider Arab–Israeli relations.

He ended his presentation emphasising that there are vast benefits for Arab countries to develop their relationship with Israel, including benefitting from the latter’s entrepreneurial, agricultural, security, energy, medical and technological expertise. Doing so can also guard Arab states against uncertainty from Washington. It can be an important and very capable and willing partner in the region for security against Iranian threats and against the threats of extremism in general. It being a country that is not so different from their own, but having achieved so much more in so many ways, Mr Isaacson believes that there is a growing desire and momentum among Arab states to get a piece of the cake and partner with Israel.

Highlights from the Question & Answer Session

Q: You seem to hint that Mr Joe Biden may not be as engaged in this project of moving forward with Middle Eastern peace as Mr Donald Trump is. Could you elaborate on that?

A: Mr Isaacson does not believe that Mr Biden has the same obsession with this issue as Mr Trump and Mr Jared Kushner’s team has. He gives the current administration a great deal of credit for single-mindedly trying to expand on Arab–Israeli peace, though he recognised that their efforts have not come to much.

Moreover, he said that their maximum pressure campaign against Iran has produced questionable results. Since the US pulled out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the Iranians have been building their stock pile of enriched uranium. They have also not ceased their aggression in the region, and continued to exert themselves in Syria, against Saudi infrastructure, and through their arming of Hizballah in Lebanon. However, the belligerence of the US towards their common Iranian enemy has earned this country credit in Sunni Gulf capitals. Moreover, its willingness to make transactional deals with these states has helped pushed forwards peace with Israel. So while America’s approach to the Iranian and Palestinian issues remain inconclusive, its approach towards the wider Arab world has been successful, he said.

Even if Mr Biden wins, he did not think that this process would stop, because it has its own internal momentum. There are good enough reasons for Arab states to move forward toward peace with Israel. A common enemy, shared opportunities and the fact that the ice has already been broken by the UAE and Oman are promising signals of this. He does not see Mr Biden stopping this process, but he also does not see him putting the same level of energy into it as the current administration has.

Q: While the Palestinian issue has been receding among Arabs, how much do you think it is receding among Muslims in general, especially in Malaysia and Indonesia?

A: Mr Isaacson said that he has reason to believe that they are watching these developments closely and that the advantages of improving their ties with Israel are increasingly apparent. He suggests that if leaders in the Muslim world can engage with political and grassroots organisations to curb any mobilisations against opening up to Israel, they would take their relationship with the country forward as there as many benefits of doing so as he mentioned in his talk. He expressed hope that that the adherence to the “solving the Israeli–Palestinian conflict first” mentality dissolves as it has in parts of the Gulf and other states.

Q: Do you see tourism and business booming between Israel and the Arab world? And do you think the F-35 deal between the UAE and the US will proceed?

A: Mr Isaacson said that two weeks ago, Khaleej Times, a English-language newspaper in the UAE, published a Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year Holiday) insert in its daily paper. In fact, on Rosh Hashanah two weeks ago, Emirati ambassador to Washington, His Excellency Yousef Al Otaibah attended a weekly religious service hosted by the Jewish Community of the Emirates via Zoom. He also brought up that 1½ years ago, a large picture book titled Celebrating Tolerance was published in the UAE. On the top left corner of the book was a picture of Mr Ross Kriel, president of the UAE Jewish Community, wearing a Jewish prayer shawl. The book had a whole chapter on the Jewish community of the Emirates. Mr Isaacson explained that this welcoming and celebration of the Jewish presence, combined with the warm welcome the Israeli team received when they were in the UAE a few days ago, reflects a very different dynamic than whatever existed between Israel and Egypt and Jordan. He expressed hope that it rubs off on other countries as well.

Speaking then about the F-35 deal, Mr Isaacson said that it has always been clear that part of the package of establishing full peace with Israel was a reassessment of the American law, called the Maintenance of Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge (QME), that requires that the US not provide weapons to the Arab world that could threaten Israel in a significant way. Because of this law, a variety of very sophisticated weapon systems have been denied Arab states that have attempted to buy them. When certain very sophisticated weaponry were sold to Arab states, they were modified in ways that would reduce the threat to Israel. Mr Isaacson said that it was clear that the UAE wanted to be in a very different category in the possibility of obtaining the most advanced American equipment; and that includes the F-35 fighter jet. There have been discussions between Emirati and US officials, and between Emirati and Israeli officials, and the prime minister of Israel has said that he has not approved the sale of the F-35 from the US to the UAE. However, it is not really an Israeli decision to make. It is an American decision, by its administration

The assurances that Mr Isaacson has been given is that such a sale would not compromise Israel’s QME for a number of reasons, like the limited volume of the sale, the particular version of the plane that the UAE will receive, and the fact that it takes years for such sales to actually materialise, in which time Israeli defence technology would have developed even further to offset any advantages that would be gained by the new buyer. This is an issue that Israeli and American defense and national security council officials are watching very closely. To sum up his response, Mr Isaacson said that the deal is moving forward, with the US president indicating that he wants to move in that direction, though the decision has yet to be finalised in the American administration.

About the Speakers

Chief Policy and Political Affairs Officer,

Global Jewish Advocacy (AJC)

Mr Jason Isaacson is the chief policy and political affairs officer for the Global Jewish Advocacy (AJC). He has played a central role in shaping the organisation’s diplomatic and political profile since assuming the position of director of Government and International Affairs in Washington, DC, in 1991, after serving in senior staff positions in the US Senate and House of Representatives and after a decade in journalism.

In addition to his broader policy responsibilities, he has focused particular attention on the Middle East — beginning with his participation as AJC’s observer in the Madrid Peace Conference in October 1991 and the launch of the multilateral Middle East peace process in Moscow the following January.

For more than a quarter century, Mr Isaacson has maintained close contact with officials and civil society leaders across the Middle East and North Africa, breaking down barriers of misunderstanding, forging common agendas, and advancing the cause of Arab–Israeli reconciliation and cooperation.