In the past few years, many things have changed in the Gulf region. Oil prices have collapsed since mid-2014, the United States has redefined its policy towards the region and Turkey is emerging as the dominant power in the Middle East. Against this background, the aim of the UAE series of papers is to provide a comprehensive, interdisciplinary understanding of how the country is responding and adapting to the new reality. The papers cover different aspects of the UAE such as the economy, demographics, society, technology, foreign policy and security.

This article shows how Abu Dhabi has shifted from its once neutral stance to a more assertive approach in dealing with regional rivalries and security threats. It outlines the contours of the grand strategy that the United Arab Emirates is developing to face what it perceives to be its two biggest security challenges today: Iran and Islamist movements.

CLICK HERE FOR THE FULL PDF.

By Jean-Loup Samaan

As a small, young state born out of the unification of seven emirates and sharing land and maritime borders with the two regional hegemons of the Gulf — Saudi Arabia and Iran — the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has traditionally perceived its security to be highly dependent on the stability of its regional environment. In the first decades of the federation, its founding father, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, crafted a foreign policy that emphasised proximity to the Western powers (namely, the United States, France and the United Kingdom), neutral if not cordial relations with neighbours and an active humanitarian programme across the Arab world. This stance was designed to avoid getting trapped into regional rivalries. But as the security situation in the region changed in the past decade, the approach of the UAE has become more proactive.

Challenges Arising from Political Change in the Middle East

Over the past decade, two phenomena have shaped the Emirati assessment of its security environment: Iran’s regional assertiveness and the rise of Islamist groups, in particular, following the social upheavals in the Arab world in 2011.

Emirati decision-makers tend to characterise Iran as a strategic challenge: a neighbouring country using proxies in countries such as Iraq, Syria, Yemen or Bahrain to defy the current balance of power and establish regional hegemony. The long-running territorial dispute between the UAE and Iran over the latter’s occupation of three Emirati islands (Abu Musa, the Great Tunb and the Lesser Tunb) adds a sense of historical grievance that has long played a role in Emirati identity-building.[1] Moreover, Iran’s ballistic missiles — the most advanced arsenal in the Gulf — shape Abu Dhabi’s perception of a concrete and immediate threat since they can easily reach the UAE’s main urban centres.[2]

But, because Iran’s ambitions are understood as a strategic challenge rather than a threat to regime survival, they have generally been treated with pragmatism by Emirati leaders. On the one hand, officials in Abu Dhabi have strongly condemned Iranian influence in the Gulf and Iran’s use of proxies. The UAE was also among the first countries to support US President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the 2015 Iran nuclear deal owing to its strong suspicion regarding Iran’s compliance. On the other hand, the country has maintained economic ties and diplomatic channels with Iran. As the UAE’s ambassador to the United States pointed out in 2016: “In the United Arab Emirates, we are seeking ways to coexist with Iran. Perhaps no country has more to gain from normalised relations with Tehran.”[3] Given the historical presence of an Iranian community in the UAE and the considerable trade relations between the two sides, Abu Dhabi’s policy towards Tehran has regularly oscillated between containment and compromise.

This stance contrasts with how the Emirati leadership deals with its second, and arguably bigger, threat, Islamist movements. This threat is deemed existential: it is seen not merely as constituting a contest for regional hegemony but rather as a threat to both regional and domestic stability.[4] The Emirati elite view movements based on political Islam as directly challenging the stability of the regional order and aimed at exploiting the “emerging political vacuum to seize power and foster instability”.[5]

In response to the threat, the UAE has developed an extensive counterterrorism approach that includes not only the fight against terrorist organisations but also initiatives against what it perceives to be their ideological foundations — “the extremist narrative” that, in the Emirati view, leads to violent extremism. This approach includes the creation of Hedayah, a global counterterrorism forum in Abu Dhabi. The UAE has fiercely opposed groups affiliated to the Muslim Brotherhood, the pan-Islamic movement founded in Egypt in 1928. Opposition to such groups, whether inside the UAE or across the whole region, has been pursued to a point that it is regularly portrayed as the central driver of the UAE’s regional policy, explaining the country’s dispute with Qatar or its support for General Khalifa Haftar in the Libyan civil war and for President Abdel Fatah el-Sisi in Egypt.[6]

Against these regional challenges, Emirati authorities generally emphasise regional stability. As Anwar Gargash, minister of state for foreign affairs and international cooperation, stated at the 2017 Manama Dialogue: “Everything we really do as the UAE is about a return to stability.”[7] One could argue that the UAE’s underlying assumption here is a pessimistic one: change in the region leads to chaos. In the words of Crown Prince Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed, “weakness leads to chaos and attracts aggressors”,[8] a point also made elsewhere by Minister Gargash: “If we have learned anything at all about the modern Middle East, it is that the region rarely gets its right when it comes to political transitions and revolution.”[9]

This approach obviously differs from the regional approach of Qatar, which has embraced — and sometimes financially supported — Islamist groups in Tunisia, Egypt, Syria and Libya, believing that supporting political transition in these countries was more effective than opposing it.[10] Eventually, the widening gap between the Emirati and Qatari approaches to the Arab upheavals led to several diplomatic crises, culminating in June 2017 with the UAE joining the Saudi-led boycott of Qatar.

The Advent of an Emirati Grand Strategy

Like the other small Gulf monarchies, the UAE has seen its partnerships with Western powers, namely the United States, France and the United Kingdom, as a key pillar of its security. In addition to signing various defence agreements with its Western partners, the UAE has allowed them to maintain significant military footprints in the country. The United States has by far the largest contingent, with 5,000 military personnel stationed at several facilities across the UAE. Additionally, since 2009, Abu Dhabi has hosted the French Command for the Indian Ocean, which has deployed 800 French soldiers in the country.

However, reliance on Western security partnerships has progressively been balanced by Abu Dhabi’s growing ambition to train a modern army that would allow the country to build strategic autonomy. The rapid growth of the UAE as a military player intervening in several regional crises (Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, Yemen) over the past decade reflects this shift. Likewise, the popular depiction of the UAE as a “little Sparta” — an expression coined by James Mattis when he was head of the US Central Command — reveals the aspiration of this small state to become a credible security actor.[11]

This new strategic posture is largely the brainchild of Mohamed bin Zayed, the deputy supreme commander of the UAE armed forces. In a 2016 speech, he unpacked the Emirati grand strategy[12] that he envisioned, emphasising six guiding principles:

- a focus on building human capital through training programmes that would enable the new generation of Emirati soldiers to achieve the goal of greater autonomy;

- massive investments in technology and military platforms that have allowed the country to operate state-of-the-art equipment and made it the seventh largest arms importer in the world during 2014–2018;[13]

- the development, through arms sales and offset programmes, of a local defence industry, which would make the country “more independent when it comes to decision-making and strategic planning” in order to “become an increasingly self-sufficient manufacturer”;[14]

- the nurturing of a strategic culture among the country’s future commanders by creating, over the past decade, a local professional military education programme following Western standards (eg, the establishment of the National Defense College, the Emirates Diplomatic Academy and the Rabdan Academy);

- regular overseas deployments of Emirati military personnel to expose them to international experiences and expertise; and

- the expansion of the armed forces through conscription, which will create closer ties between soldier and citizen.

This Emirati roadmap towards strategic autonomy is still in the making but is the direct result of both the regional assessment depicted above and the perceived US reluctance to intervene in crises in the Middle East.[15] This perception has led Emirati forces to prepare not only for territorial defence but also for expeditionary operations on a scale unprecedented for an Arab country of the UAE’s size. “Our responsibility is not limited to our homeland, and we feel a great sense of responsibility towards the security of our sisterly Arab nations”, stated Mohamed bin Zayed in May 2015, three months after the UAE had joined the Saudi-led coalition to restore the internationally recognised government in Yemen.[16]

Another major aspect of this new Emirati strategic posture is the importance conferred to new international partnerships, starting with the country’s close rapprochement with Saudi Arabia. Both countries had been at odds since the founding of the UAE in 1971. An unresolved border dispute between the two escalated in 2009.[17] But since then — and despite not having formally settled the border dispute — Riyadh and Abu Dhabi have undergone a major process of rapprochement, which has redefined the balance of power within the Gulf Cooperation Council.[18]

Today, Saudi–Emirati relations are primarily based on a convergence of views on the Gulf security agenda in the post-2011 environment, particularly regarding political Islam and Iran. The warming relationship between the two countries culminated in early December 2017 with the announcement of a formal political and military alliance.[19] Admittedly, a convergence of views does not necessarily mean identical views: in some cases, such as the war in Yemen, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have differed on the approach to Islamist forces[20] or on the desired end state. In particular, their approaches have differed on the question of who to support in Yemen — the secessionists or the Hadi government. Nonetheless, these differences so far seem more tactical than strategic.

Meanwhile, the UAE took many observers by surprise in August 2020, when it signed a normalisation agreement with Israel. It was no secret that strategic and economic exchanges between both countries had steadily developed over the previous decade, but there was no obvious indication that these would be followed by the formalisation of diplomatic relations. After a joint statement on the agreement, issued by the US administration, UAE officials promoted the idea that the “Abraham Accord” constituted a peace agreement suspending Israel’s plans for the annexation of the West Bank, but the political motivations behind normalisation were to be found elsewhere. The commonality of views between Israeli and Emirati decision-makers on threats such as Iran and political Islam, and the Emirati interest in acquiring Israeli defence and security equipment (particularly in subsectors such as cybersecurity and artificial intelligence) certainly explained the decision. But Abu Dhabi’s desire to improve its public image in the United States probably played an equal role in its shift towards normalisation.[21]

Finally, Abu Dhabi has been keen on developing close ties with India and China. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi invited Mohamed bin Zayed to India as chief guest at India’s Republic Day in 2017. Since then, India and the UAE have signed numerous partnership agreements (eg, agreements for investments in Indian infrastructure, and for counterterrorism and maritime security cooperation). At the same time, Emirati officials have positioned the country as the most active partner of China in the region: for instance, Abu Dhabi Ports signed a 35-year concession agreement with China’s Cosco Shipping, which aims to turn the port into the main point of entry in the peninsula for Chinese ships.[22] These new partnerships do not constitute a departure from Abu Dhabi’s traditional proximity to Western powers; instead, they constitute a process of diplomatic diversification to achieve greater strategic autonomy.

Prospects

The military, economic and diplomatic influence of Abu Dhabi in the Gulf region reflects its current leadership’s perception that shaping developments in the Arab world is important to the protection of the regime. This emerging grand strategy may look ambitious for such a small state. As in the case of any state with international ambitions, there is a financial and human cost to such ambitions. Although there are no official statistics on the expenditure incurred by the UAE in the war in Yemen, the protracted conflict has been a hard lesson for Abu Dhabi on the constraints of expeditionary wars, a fact that Western armed forces have been experiencing for decades now.

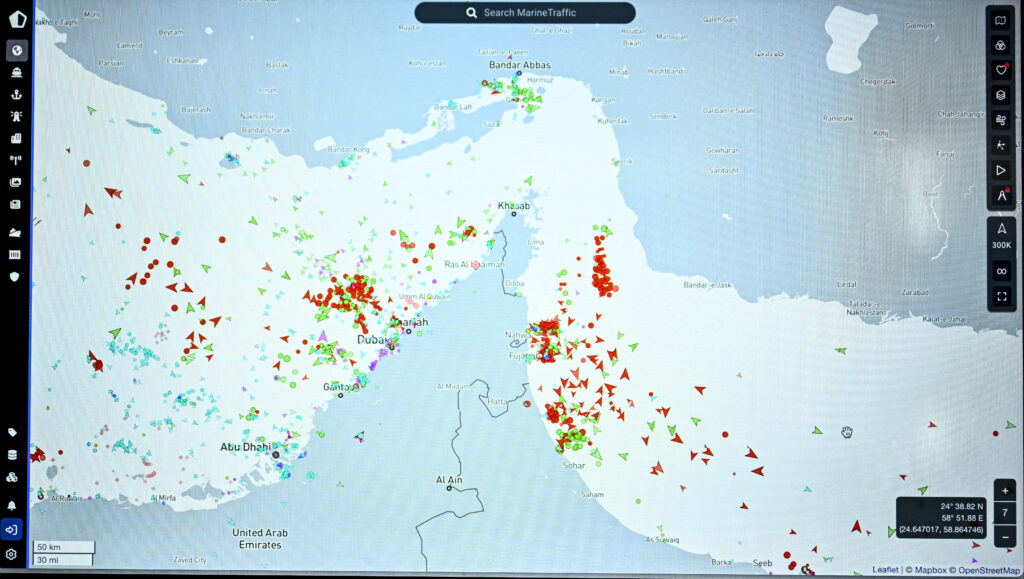

As a new strategic culture emerges in Abu Dhabi policy circles, one of the main challenges for the UAE will be to demonstrate its flexibility and, more precisely, its ability to adapt in the face of unexpected regional events and strike compromises where necessary. In particular, the longstanding competition with Iran, with its potential for regional escalation, is a litmus test for Emirati statecraft. Observers were taken by surprise by the way Abu Dhabi reacted to the May 2019 crisis with Iran over the sabotage of tankers in the Strait of Hormuz. Abu Dhabi’s call on all sides to show restraint and its opening of dialogue with Tehran to avoid open confrontation was a demonstration of much-needed pragmatism. In fact, the decision was a reminder of how much the stability of the UAE is exposed to regional crises. Whether Abu Dhabi will be able to demonstrate similar flexibility on other pressing issues will be critical to its aspirations of achieving strategic autonomy while navigating between its Western allies, its neighbouring powers in the Gulf and emerging Asian players.

About the Author

Dr Jean-Loup Samaan is a research affiliate of the Middle East Institute, National University of Singapore.

Image caption: The Ain Dubai observation wheel in Dubai, UAE. Shared by Jonathan Bowen on Wikimedia Commons

Footnotes

[1] Thomas Mattair, The Three Occupied UAE Islands: The Tunbs and Abu Musa (Abu Dhabi: Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research, 2005).

[2] Anthony Cordesman, “The Iranian Missile Threat”, Center for Strategic & International Studies, 30 May 2019, https://www.csis.org/analysis/iranian-missile-threat.

[3] Yousef Al Otaiba, “One Year After the Iran Nuclear Deal”, The Wall Street Journal, 3 April 2016.

[4] For a fair account of the Emirati view, see the book on political Islam by the influential foreign policy thinker Jamal Sanad Al Suwaidi, The Mirage (Abu Dhabi: Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research, 2015).

[5] Anwar Gargash, “The New Arab Awakening”, Foreign Policy, 9 July 2013.

[6] Congressional Research Service, “The United Arab Emirates: Issues for US Policy”, Washington, 19 August 2019, 2.

[7] The IISS Manama Dialogue 2017, “Political and Military Responses to Extremism in the Middle East: Dr Anwar Mohammad Gargash”, Second Plenary Session, 9 December 2017, https://www.iiss.org/events/manama-dialogue/manama-dialogue-2017.

[8] Crown Prince Court, “Statement by HH Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the UAE Armed Forces, on the 40th Anniversary of the Unification of the UAE Armed Forces”, 5 May 2016, https://www.cpc.gov.ae/en-us/mediacenter/Pages/Speeches.aspx.

[9] Anwar Gargash, “Our solution for Libya”, The National, 19 May 2019.

[10] David Roberts, “Qatar and the UAE: Exploring Divergent Responses to the Arab Spring”, Middle East Journal 71, no. 4 (Autumn 2017): 544–562.

[11] Rajiv Chandrasekaran, “In the UAE, the United States has a quiet, potent ally nicknamed ‘Little Sparta’”, The Washington Post, 9 November 2014.

[12] Here we use the concept of grand strategy in the sense used by Barry Posen, ie, as “a political-military, means-ends chain, a state’s theory about how it can best ‘cause’ security for itself”. See Barry Posen, The Sources of Military Doctrine: France, Britain, and Germany Between the World Wars (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986), 13.

[13] Pieter D Wezeman, Aude Fleurant, Alexandra Kuimova, Nan Tian, and Siemon T Wezeman, “Trends in International Arms Transfers”, SIPIR Fact Sheet, March 2019, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2019-03/fs_1903_at_2018.pdf.

[14] Crown Prince Court, “Speech by HH Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the UAE Armed Forces, on the Occasion of the 39th Anniversary of the Unification of the Armed Forces”, 4 May 2015, https://www.cpc.gov.ae/en-us/mediacenter/Pages/Speeches.aspx. See also Jean-Loup Samaan, “The Rise of the Emirati Defense Industry”, Sada, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 14 May 2019, https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/79121.

[15] Gargash, “Our solution for Libya”.

[16] Crown Prince Court, “Speech by His Highness Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the UAE Armed Forces, on the Occasion of the 39th Anniversary of the Unification of the Armed Forces”.

[17] On the background to the dispute, see Noura Saber Al-Mazrouei, The UAE and Saudi Arabia: Border Disputes and International Relations in the Gulf (London: IB Tauris, 2016).

[18] On the regional impact of the Saudi–Emirati alliance as depicted by an Emirati scholar, see the analysis of Abdulkhaleq Abdulla, Lahza al khaleej fi at Tarikh al Arabi al Mu’asir (Dubai: Dar Al Farabi, 2018).

[19] Patrick Wintour, “UAE announces new Saudi alliance that could reshape Gulf relations”, The Guardian, 5 December 2017.

[20] Michael Horton, “The Battle for Yemen: A Quagmire for Saudi Arabia and the UAE”, Terrorism Monitor, Jamestown Foundation, 19 May 2017, https://jamestown.org/program/battle-yemen-quagmire-saudi-arabia-uae/.

[21] Jim Zanotti and Kenneth Katzman, “Israel–UAE Normalization and Suspension of West Bank Annexation”, Congressional Research Service, 19 August 2020.

[22] Jeffrey Becker, Erica Downs, Ben DeThomas and Patrick deGategno, China’s Presence in the Middle East and Western Indian Ocean: Beyond Belt and Road, Center for Naval Analyses, Washington, DC, February 2019, 88.