By Melissa Gronlund

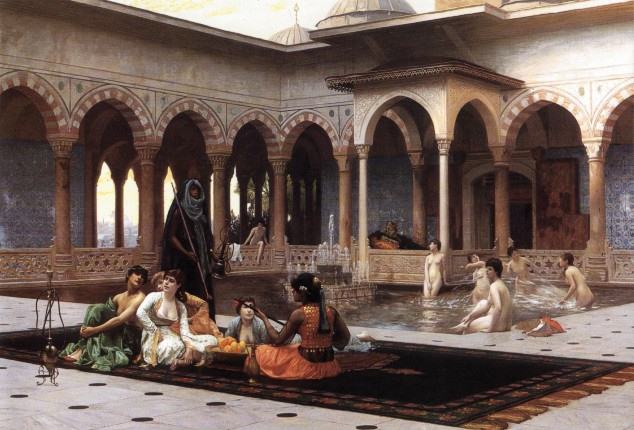

In a courtyard rimmed by a brightly tiled colonnade, women sit on a dark carpet, surrounded by two male guards in swaths of fabric. Their low-cut dresses are turned suggestively toward the painting’s viewer; behind them, naked women splash each other in the pool. One extends a nude leg over a balustrade to join in, her clothes hanging to one side. The scene is the stuff of male fantasy — which, of course, it was. Painted by the prominent French orientalist, Jean-Léon Gérôme, in 1898, The Terrace of the Seraglio is one of a number of depictions of the harem, the women-only section of Ottoman palaces that captured the imagination of the European painters, who, though they would never have been able to enter them, nevertheless put brush to canvas to popularise these living quarters as sites of sexual availability.

In the age of #metoo and greater awareness in global thinking, orientalism would seem ripe for cancellation. Arabs come off as indolent, work-shy; women are routinely sexualised and if not depicted half-clothed in harems or as submissive peasants, are shown carrying water jugs atop their heads with one hip cocked to the side. Swept up in the European interest in the Middle East that began roughly with Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798, mostly male and mostly European artists played fast and loose with historical accuracy of their subject. Many never even visited the region while and others worked up their paintings back in their Paris studios from memories, sketches and the artefacts they brought home.

Intellectually, the genre, which populated literature as well as canvases, has not aged well. Indeed, you might think Orientalism has already been cancelled; Edward Said’s magisterial critique of its imperialist and colonialist basis, written in 1978, has eclipsed its art-historical and literary subjects in cultural importance. But over the past 15 years, the paintings themselves have soared in popularity. They are being bought by Islamic and Arab collectors and appearing in institutions from the British Museum to Louvre Abu Dhabi. To these collectors, orientalism is not colonialist kitsch, but a celebration of the Middle Eastern world before it became modernised and Westernised. The complex rites of Ottoman palaces, the sumptuously clothed guards and men in reverent lines at prayer, all painted with virtuoso naturalism and in finely rendered detail — these works add substantially to the visual record of the 19th century Islamic world.

Just because orientalism is being collected, of course, doesn’t mean it should be rehabilitated. But “cancel culture”, though hot-blooded and well-intentioned, is also provincial and narrowly focused. The subtext of the orientalist revival is the decline of the West and the shifting of power and money to new players on the economic stage — forces that eclipse academics’ and the twittersphere’s realm of influence.

Gulf Arabs have been major buyers of orientalist work since Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Bonhams began holding sales in Doha and Dubai in the mid-2000s and orientalism is now sought after by institutions in the Gulf’s museum boom. As these museums chart a path between western art forms and display methods on the one hand and art histories and idioms from the local region on the other, orientalist paintings provide a rare example of a visual cultural meeting point.

One of the largest collections of orientalist work is in Qatar’s Orientalist Museum, not yet open to the public. Louvre Abu Dhabi is also a player; its painting of a young scholar reading, by the Turkish artist Osman Hamdi Bey (one of the few non-European orientalists), has become one of its most famous works, emblazoned on museum tickets and marketing material.

In Kuala Lumpur, Syed Mohamad Albukhary has built up a substantial collection of orientalist work as director of the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia (IAMM). The museum loaned key works to the British Museum for its current exhibition on orientalism, “Inspired by the East: How the Islamic World Influenced Western Art”, which paired IAMM’s orientalist paintings with the material objects in its own collection — a neat (and revealing) reversal, as the British Museum’s artefacts originally came from the Islamic world, and the paintings from Europe. It’s interesting to see who the lenders and donors are now: Syed Mohamad Albukhary is also the brother of the philanthropist Syed Mokhtar Albukhary, who sponsored the renovation of the British Museum’s Islamic Arts galleries.

There’s a danger here that orientalism becomes rebranded as a site of genuine cultural exchange. It wasn’t. Though some painters lived for a time in the Middle East and some developed deep relationships with the region, orientalism is more productively to be considered as part of the history of the global tourist trade, an engine of imbalanced cultural exchange and one that establishes economic dependencies that still persist in places like Morocco.

But the market-led rehabilitation of the genre is performing its own, invisible-hand cancellation of some of orientalism’s more egregious elements. Harem paintings have lost popularity among buyers (at least according to publicly available data): Sotheby’s recent sale of part of the feted Najd Collection, a pre-eminent Saudi-based collection, eschewed paintings of the subject. The British Museum, in its typology of orientalism’s main subjects, shunted the harem works apologetically off to one side.

Rather giving a binary yes or no to the subject, orientalism is simply evolving into a new phase. From Scottish kilts to German Christmas traditions, many communities have incorporated 19th-century embellishments into now ongoing customs. Orientalism is adding itself to that global list. SYNDICATION BUREAU

About the Author

Ms Melissa Gronlund is a writer on art based between Abu Dhabi and London. Her writing has appeared in Artforum, L’Hebdo d’Art, BOMB, e-flux journal and The New Yorker, among other publications. From 2007 to 2014, she lectured on contemporary art at Oxford University’s Ruskin School of Drawing & Fine Art.

Image caption:

The Terrace of the Seraglio by Jean-Léon Gérôme. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.