Small states are generally assumed to be on the receiving end of power in the international arena rather than a source of it. But, from the late 1990s to mid-2013, when Sheikh Hamad Al Thani ruled the country, Qatar became endowed with a form of power that did not conform to either traditional conceptions of “hard power”, or “soft power”, rooted in the attraction of norms, or even a combination of the two, “smart” power. Qatari foreign policy then comprised four primary components: hedging, military security and protection, branding and hyperactive diplomacy, and international investments. Combined, they bestowed Qatar with a level of power and influence far beyond its status as a small state and a newcomer to regional and global politics. This form of power, consisting of often behind-the-scenes agenda setting, can be best described as “subtle power”.

CLICK HERE FOR THE PDF

By Mehran Kamrava

That Qatar, in the latter years of the rule of former emir Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani (r. 1995–2013), was able to create a distinct niche for itself on the global arena, that it played on a stage significantly bigger than its stature and size warranted, that it emerged as a consequential player not just in the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Peninsula but indeed across the Middle East and beyond all bespeak its possession of a certain type and degree of power. By definition, that power cannot be “hard” or “soft” power, or their combination, “smart” power. Flush with inordinate wealth, Qatar could be easily thought of as endowed with economic power, which the country certainly had then and still does. But there was more to Qatar’s international standing and its place and significance within the world community than simple economic power. At least insofar as Qatar is concerned — and perhaps for comparable countries with similar sizes, resources, and global profiles, such as Switzerland and Singapore — a different conceptualisation of power may be more apt. From the late 1990s to 2013, Qatar may be said to have acquired for itself what may best be viewed as “subtle power”. This paper examines what subtle power is and how Qatar has deployed it.

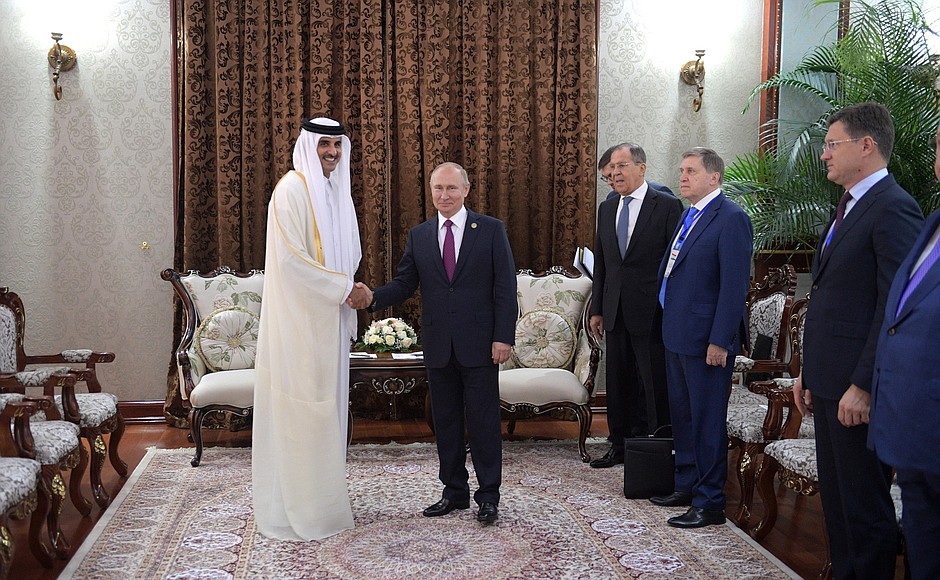

No form of power lasts forever, and subtle power is no exception. When Sheikh Hamad stepped down from power in June 2013, his son and successor, Sheikh Tamim, began pursuing a deliberately different foreign policy strategy that both reoriented his country’s international relations and slowly put an end to its subtle power.

Varieties of power

There are four key components to subtle power (see Table 1). The first involves safety and security as guaranteed through physical and military protection. This does not necessarily involve force projection and the imposition of a country’s will on another through coercion or inducement. This sense of security may not even be internally generated but could come in the form of military and physical protection provided by a powerful patron — say, the United States. It simply arises from a country’s own sense of safety and security. Only when a state is reasonably assured that its security is not under constant threat from domestic opponents or external enemies and adversaries can it then devote its attention and resources to building up international prestige and buying influence. A state preoccupied with setting its domestic house in order, or paranoid about plots by domestic or international conspirators to undermine it, has a significantly more difficult time trying to enhance its regional and global positions than a state with a certain level of comfort about its stability and security. The two contrasting cases of Iran, whose intransigent regime is under constant threat of attack from Israel or the United States, and that of Qatar, which is confident of US military protection but aggressively pursues a policy of hedging, are quite telling.

Table 1. Key elements of subtle power

Source Manifestation

Physical and military protection >> Safety and security

Marketing and branding efforts >> Prestige, brand recognition, and reputation

Diplomacy and international relations >> Proactive presence as global good citizen

Purchases and global investments >> Influence, control, and ownership

A second element of subtle power is the prestige that derives from brand recognition and developing a positive reputation. Countries acquire a certain image as a result of the behaviours of their leaders domestically and on the world stage, the reliability of the products they manufacture (especially automobiles and household appliances), their foreign policies, their responses to natural disasters or political crises, the scientific and cultural products their export such as movies, the commonplace portrayals of a country and its leaders in the international media, and the deliberate marketing and branding efforts they undertake. When the overall image that a country thus acquires is positive — when, in Nye’s formulation, it has “soft power”[1] — then it can better position itself to capitalise on international developments. By the same token, soft power enables a country to ameliorate some of the negative consequences of its missteps and policy failures.[2]

Sometimes a positive image builds up over time. Global perceptions of South Korea and Korean products is a case in point. Despite initial reservations by consumers when these products first broke into American and European markets in the 1980s, today Korean manufactured goods enjoy generally positive reputations in the United States and Europe.[3] At other times, as in the cases of Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and Qatar, political leaders try to build up an image and develop a positive reputation overnight. They hire public relations firms, take out glitzy advertisements in billboards and glossy magazines around the world, buy world-famous sports teams and stadiums, sponsor major sporting events that draw world-renowned athletes and spectators from across the world, spare no expenses in putting together national airlines that consistently rank at or near the top, spend millions of dollars on international conferences that draw to their shores world leaders and global opinion-makers, and build entire cities and showcase buildings that are meant to rival the world’s most magnificent landmarks.

This positive reputation is in turn reinforced by a third element of subtle power, namely, a proactive presence on the global stage involving a deliberately crafted diplomatic posture aimed at projecting — in fact, reinforcing — an image of the country as a global good citizen. This is also part of a branding effort, but it takes the form of diplomacy rather than deliberate marketing and global media advertising. In Qatar’s case, this diplomatic hyperactivism was part of a hedging strategy, as compared to bandwagoning or balancing, that has enabled the country to maintain open lines of communication, if not altogether friendly relations, with multiple international actors that are often antagonistic to one another (such as Iran and the United States). What on the surface may appear as paradoxical, perhaps even mercurial, foreign policy pursuits was actually part of a broader, carefully nuanced strategy to maintain as many friendly relationships around the world as possible.

Not surprisingly, in the late 1990s and the early 2000s Qatar sought to carve out a diplomatic niche for itself in a field meant to enhance its reputation as a global good citizen, namely, mediation and conflict resolution.[4] In a region known for its internal and international crises and conflicts, Qatar until recently had, largely successfully, carved out an image for itself as an active mediator, a mature voice of reason calming tensions and fostering peace. The same imperative of appearing as a global good citizen were at work in Qatar’s landmark decision to join NATO’s military campaign in Libya against Colonel Qaddafi beginning in March 2011. Speculation abounded at the time as to the exact reasons that prompted Qatar to join NATO’s Libya campaign.[5] Clearly, as with its mediation efforts, Qatar’s actions in Libya were motivated by a hefty dose of realist considerations and calculations of possible benefits and power maximisation.[6] But the value of perpetuating a positive image through “doing the right thing”, at a time when the collapse of the Qaddafi regime seemed only a matter of time, appears to trump other considerations.

The final and perhaps most important element of subtle power is wealth, a classic hard power asset. Money provides influence domestically and control and ownership over valuable economic assets spread around the world. This ingredient of subtle power is the influence and control that is accrued through persistent and often sizeable international investments. As such, this aspect of subtle power is a much more refined and less crude version of “dollar diplomacy”, through which regional rich boys seek to buy off the loyalty and fealty of the less well endowed. Although by and large commercially driven, these investments are valued more for their long-term strategic dividends than for their shorter term yields. So as not to arouse suspicion or backlash, these investments are seldom aggressive. At times, they are framed in the form of rescue packages that are offered to financially ailing international companies with well-known brand names. Carried through the state’s primary investment arm, the sovereign wealth fund (SWF), international investments were initially meant to diversify revenue sources and minimise the risk from heavy reliance on energy prices. The purported wealth and secrecy of SWFs has turned them into a source of alarm and mystique for Western politicians and has ignited the imagination of bankers and academics alike.[7]

Qatar and the pursuit of subtle power

Qatar’s emergence as a significant player in regional and international politics was facilitated through a combination of several factors, chief among which were a very cohesive and focused vision of the country’s foreign policy objectives and its desired international position and profile among the ruling elite, equally streamlined and agile decision-making processes, immense financial resources at the hands of the state, and the state’s autonomy in the international arena to pursue its foreign policy objectives.

It is important to see what, if any, generalisable conclusions can be drawn from the Qatari example concerning the study of power and also small states. Insofar as power is concerned, the Qatari case demonstrates that traditional conceptions of power, while far from having become altogether obsolete, need to be complemented with other elements arising from new and evolving global realities. For some time now, observers have been speculating about the steady shift of power and influence away from its traditional home for the last 500 years or so — namely, the West — in the direction of the East. In Zakaria’s words, the “post-American world” may already be upon us.[8] Whatever this emerging world order will look like, it is obvious that the consequential actions of a focused and driven wealthy upstart like Qatar cannot be easily dismissed. Even if the resulting changes are limited merely to the identity of Qatar rather than to what it can actually do, which they are not, they are still consequential far beyond the small sheikhdom’s borders. Change in the identity of actors — in how they perceive themselves and are perceived by others — can lead to changes in the international system.[9] Qatar may not have re-drawn the geostrategic map of the Middle East — and whether that was what it indeed sought to do is open to question. But its emergence as a critical player in regional and global politics is as theoretically important as it was empirically observable.

Qatar’s location in an ever-changing and notoriously unpredictable region introduced several imponderable variables. Clearly, one of the primary reasons for Qatar’s ability to exercise subtle power in the late 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s was the regional context: Iraq was both internationally isolated and marginalised and simply incapable of exerting much power beyond its own borders; Iran was not in a much better position and could only buy the loyalty of non-state actors near and far; Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE were all saddled with stale and ageing leaderships that had neither the wherewithal nor the desire to exert regional leadership; and revenues from gas and oil sales only kept rising. Qatar, in other words, was enjoying a fortuitous “moment in history.”[10]

The regional context had already begun to change by the time the chief architects of Qatar’s subtle power departed from the scene in 2013. The 2011 Arab uprisings jolted the Saudi leadership into action, prompting them to take the lead in a counter-revolution of sorts to reverse the tide of the Arab Spring in order to ensure the survival of their own and Bahrain’s monarchies.[11] In Syria and Iraq, the Arab Spring, whose early manifestations Qatar so triumphantly capitalised on, turned into a nightmare of a religious extremism that put Al-Qaeda to shame. By 2015, with political leadership having effectively passed into the hands of a younger and more restless generation in both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, Saudi Arabia and the UAE rallied other Arab allies to join them in a relentless (though not fully successful) military campaign in Yemen — the most direct and violent form of hard power — despite continuing, and drastic, drops in the price of oil and gas in global markets.

Qatar’s young emir, only in his early 30s, found his country in a regional environment that was decidedly different from the one his father had enjoyed in his final years of rule. This evolving regional context shaped emir Tamim’s decision not to actively pursue policies that foster subtle power. Thus, after 2013, Qatar’s subtle power came to an end.

About the author

Mehran Kamrava is Professor and Director of the Center for International and Regional Studies at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service in Qatar. He is the author of a number of journal articles and books, including, most recently, Troubled Waters: Insecurity in the Persian Gulf (Cornell University, 2018); Inside the Arab State (Oxford University Press, 2018); The Impossibility of Palestine: History, Geography, and the Road Ahead (Yale University Press, 2016); The Modern Middle East: A Political History since the First World War, 3rd ed. (University of California Press, 2013); and Iran’s Intellectual Revolution (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

[1] Joseph S. Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York: Public Affairs, 2004), 5.

[2] Referring to two highly popular American television shows, van Ham makes the following observation: “As long as America presents the world with its Desperate Housewives and Mad Men, it seems to get away with policy failures like Iraq.” Peter van Ham, Social Power in International Politics (London: Routledge, 2010), 164.

[3] Consumers tend to form attitudes towards products based on perceptions of the products’ country of origin, and, vice versa, their perceptions of products originating from a particular country tend to influence their attitudes towards that country. There are “structural interrelationships between country image, beliefs about product attitudes, and brand attitudes.” C. Min Han, “Country Image: Halo or Summary Construct?” Journal of Marketing Research 26, (May 1989): 228.

[4] See, Mehran Kamrava, “Mediation and Qatari Foreign Policy,” Middle East Journal 65, No. 4 (Autumn 2011): 1–18.

[5] Peter Beaumont, “Qatar accused of interfering in Libyan affairs,” Guardian, 4 October 2011, 22.

[6] Reuters, “Qatar’s Big Libya Adventure,” Arabianbusiness.com, June 13, 2011; Andrew Hammond and Regan Doherty, “Qatar hopes for returns after backing Libyan winners,” Reuters.com, 24 August 2011.

[7] A number of studies have empirically demonstrated that the sizes of SWFs have often been grossly exaggerated. See, for example, Jean-Francois Seznec, “The Gulf Sovereign Wealth Funds: Myths and Reality,” Middle East Policy 15, No. 2 (Summer 2008): 97–110; Jean-Francois Seznec, “The Sovereign Wealth Funds of the Persian Gulf,” in The Political Economy of the Persian Gulf, ed. Mehran Kamrava (New York, Columbia University Press, 2012), 69–93; and, Christopher Balding, “A Portfolio Analysis of Sovereign Wealth Funds,” in Sovereign Wealth: The Role of State Capital in the New Financial Order, eds. Renee Fry, Warwick J McKibbin, and Justin O’Briens (London: Imperial College Press, 2011), 43–70.

[8] Fareed Zakaria, The Post-American World (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008).

[9] Richard Ned Lebow, A Cultural Theory of International Relations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 442.

[10] Mehran Kamrava, Qatar: Small State, Big Politics (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015), 165.

[11] Mehran Kamrava, “The Arab Spring and the Saudi-Led Counterrevolution,” Orbis 56, No. 1 (Winter 2012) 96–104.

Image caption: Qatari Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani meeting Russian President Vladimir Putin at the sidelines of the CICA Summit in June this year. Photo: Official Website of the Russian President (kremlin.ru)