By Hasan Alhasan

While the world fixates on the West’s response to the 14 September attack on Saudi Aramco, the oil giant’s largest customers in Beijing, New Delhi, Tokyo and Seoul have hidden behind feeble condemnations of an incident that threatens to undermine the global economy. The timid response of the four Asian powers betrays the absence of any strategy in Asia’s capitals for dealing with security in the Gulf if, or when, the Americans decide they no longer want to get involved.

The Aramco attack represents a turning point in the Gulf’s regional security paradigm. Since the 1980s at least, the Gulf’s regional security architecture has been predicated on the assumption that the US would intervene militarily to protect its own vital interests, especially oil. This assumption was proven in spectacular fashion when President George HW Bush authorised military intervention to expel Saddam Hussein’s troops from Kuwait in the Gulf War of 1990–91.

The disruptive effect of the Aramco attack has exceeded that of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, but President Donald Trump’s mixed reaction suggests that the era of America’s security guarantee, or Pax Americana, in the Gulf may be coming to an end. Initially, Mr Trump tweeted that his country was “locked and loaded” to face Iran. He later tempered his position, arguing that as a net oil exporter the US did not “need Middle Eastern oil & gas”.

As is often the case, Mr Trump’s claim was mere hyperbole; in 2017, the US sourced one fifth of its crude petroleum imports from the Gulf, according to data compiled by the Observatory of Economic Complexity at MIT, and the US remains exposed to price volatility in global oil and gas markets.

The gradual unravelling of the Gulf’s regional security apparatus has left the Asian powers in disarray. Asian economies have grown to be heavily dependent on oil imports to satisfy growing demand, a baseline figure that ranges from 70 per cent in China to almost 100 per cent in Japan, according to the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. Crucially, Asian economies purchase most of this oil from the Gulf. As a share of oil imports, the Gulf region accounted for between 44 per cent in China and 86 percent in Japan, with India (63.6 per cent) and South Korea (77.1 per cent) falling in between, according to 2017 data compiled by the Observatory of Economic Complexity. Moreover, Saudi Arabia tops the list of import sources across the board, except in India where it closely trails Iraq.

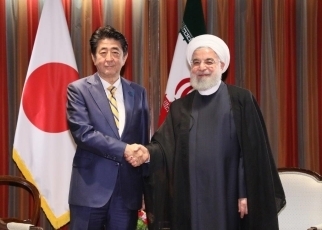

Reflecting this dependency, the Asian powers have repeatedly been victimised of late by growing regional tensions in the Gulf. In June, a mine attack attributed to Iran blew a hole in the hull of a Japanese oil tanker moored at the UAE port of Fujairah, only hours after Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had been to Tehran to seek de-escalation. In July, up to 30 Indian sailors on board British and Panama-flagged tankers were detained by Iranian naval forces in the Gulf, although some have since been freed.

The most recent attack on Saudi Aramco using cruise missiles and drones, however, constitutes an unprecedented escalation by Iran and a willingness by Tehran to put the global economy at risk. Oil prices spiked after the attack, with Brent crude climbing 20 per cent to over US$71 a barrel at one point. Due to their dependence on imports and growing demand for energy, Asian economies are acutely sensitive to changes in global energy prices. In India for instance, a US$10 increase in per barrel oil prices is associated with a 0.2 percentage point drop in GDP growth, according to Nomura.

To make matters worse, the targeted facilities in Abqaiq and Khurais alone supply Asian economies with 2.5 to 2.7 million barrels of oil per day, according to the energy consulting firm Wood Mackenzie. Despite assurances from Saudi Aramco, Japanese refiners and supertankers shipping oil to China and India have reportedly been notified of changes in crude grade from light to heavy or medium, according to Reuters, prompting a scramble for short-term alternatives. Although China, Japan and South Korea boast considerable strategic reserves, analysts at Wood Mackenzie say plugging the gap with the appropriate grade of crude oil could prove to be a challenge if shortages last. India’s reserves, meanwhile, are woefully inadequate, amounting to only a fraction of what its Asian peers have stored away.

In recent years, growing investments by Asian national energy companies in upstream oil and gas projects in the Gulf have also upped their nations’ stakes in the region’s stability. In 2018, Abu Dhabi’s Adnoc alone signed deals worth US$1.6 billion with China’s CNPC and US$600 million with India’s ONGC Videsh in upstream oil. Given the precision of the Aramco attack, other major oil producers, including the UAE and Kuwait, are clearly just as vulnerable as Saudi Arabia to Iranian missiles and drones laden with explosives.

Yet, the response from Asian powers to the attack – attributed so far by the US, the UK, France, Germany and Saudi Arabia to Iran — has been distinctly underwhelming. In their condemnations, none has pointed the finger at Iran or indicated a willingness to impose costs for future provocations. Japan’s defense minister ruled out military action because it is against his country’s constitution, while India has consistently eschewed US-led collective security arrangements in the Gulf and Horn of Africa.

Finally, as the Asian powers continue to sit out any attempt to punish or deter future Iranian aggression, their relationship with the Gulf region appears likely to remain transactional. Despite their growing military capabilities and economic clout, Asian powers seem unlikely to transition to a strategic role in the Gulf anytime soon. As Asian powers shirk broader security responsibilities in the Gulf and the US recalibrates its global security commitments, instability may become the norm in a region that is still a vital source of energy for the world. SYNDICATION BUREAU

About the Author

Mr Hasan Alhasan is a researcher at the India Institute at King’s College London and an associate fellow at the International Institute of Strategic Studies. Previously, he served as a senior analyst at the Office of the First Deputy Prime Minister of Bahrain.

Caption for image:

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe meeting Iranian President Hassan Rouhani at a Japan-Iran Summit meeting on 24 September. The meeting was held on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly session. Photo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan