Following the Trail of a Peacock, from Northern Iraq to Singapore and Beyond (part 5)

- -

Many years ago, when I was studying Sundanese kebatinan (mystical-magical) movements in West Java, one of the gurus of the cult known as Abdul Jabar told me a creation myth in which a peacock played a role as a secondary creator or demiurge. In my field notes, I summarised the myth:

“In the beginning, Dzatullah created light, and out of light became the bird Taus, the haughty peacock. And the mirror was also created. The peacock, seeing itself in the mirror, began to sweat. And the drops of sweat dripping from his body turned into angels.” (interview with Mama Ili, Bandung, 1 June 1984)

I may not have caught all the finesses of the myth at the time, but it brought the Yezidis’ Peacock Angel to mind, who plays a somewhat similar role in Yezidi theology. The Abdul Jabar cult was focused on harnessing the powers of angels, jinns, and divine names for various worldly purposes such as healing and the martial arts, as well as for spiritual and mental advancement. (One of the persons who brought me into contact with the cult was my teacher of the Sundanese pencak silat, the local form of martial arts.) The cult’s founder had adopted the name of Abdul Jabar because of the very special powers inherent in the divine name Jabbār (‘Almighty’, ‘Omnipotent’). The emblem of the cult was the image of a bird consisting of the calligraphed words `Abd and Jabbār. Some called the bird a Garuda, but Abdul Jabar’s son Ishaq, whom I later came to know well, told me that it represented the peacock of the creation story.

Abdul Jabar emblem embroidered on a red kerchief (the colour associated with martial arts)

The Abdul Jabar emblem on the founder’s grave

Not much later, I discovered that a more elaborate version of this creation myth is being kept alive and is re-enacted every year in a unique festival celebrated in South Sulawesi, the Maudu’ Lompoa of Cikoang. The peacock, in this myth, is a manifestation of the Light of Muhammad, the prophetic essence that was created before the angels and the humans, and that would reach its most perfect embodiment at the birth of the Prophet Muhammad. The Creator placed the Peacock on a cosmic tree with four main branches, known as the Tree of Certainty (shajarat al-yaqīn) or Tree of the Faithful (shajarat al-muttaqīn).

Cikoang is a fishers’ settlement on the Southwestern tip of Sulawesi. Like many other fishing villages, the community makes an annual offering to the sea to ward off danger. In Cikoang, unlike elsewhere, this occurs on the occasion of Mawlid, the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad, in a ritual directed by a family of sayyids (descendants of the Prophet) who have been living among the fishermen for centuries. It is these sayyids who have carefully guarded the tales of the Prophet’s birth as well as the myth of Nur Muhammad, the Muhammadan Light, as a divine emanation or as the first created entity. According to old Malay books to which the sayyids refer, Nur Muhammad was a light made of precious material in the form of a peacock, seated on a cosmic tree. Both the tree and the peacock are represented in the festive offerings the community.

I first read about the sayyids of Cikoang and their colourful Mawlid festival in an article by the French scholar Gibert Hamonic (‘La fête du grand Maulid a Cikoang, regard sur une tarekat dite “shiite” en Pays Makassar’, Archipel 29, 1985, 175-192). His photographs, and the story of peacock and tree reminded me of the Thaipusam procession I had witnessed a few years earlier. People carried a wooden construction on their shoulders that vaguely resembled the kavadi carried by women in the Thaipusam procession. The construction, which had four legs, was called kandawari and represented the cosmic tree and its four branches. Like the kavadi, it was embellished with banners and other objects that might be taken to represent peacock feathers.

Kandawari, carried by men on their shoulders

[from Hamonic’s Archipel article]

The Malay texts about Nur Muhammad to which the Cikoang sayyids referred were once widely read, and when I started collecting books in Arabic script in the late 1980s, I found some of them still on sale in bookshops in isolated places in Kalimantan and Malaysia, but they were no longer part of the curriculum of pondok and pesantren, if they had ever been. Reformers had, I suppose, condemned these works as superstitious and purged them from the shelves of the more respectable establishments. (The texts are discussed and summarised, however, by Mohd. Nor bin Ngah in his Kitab Jawi: Islamic thought of the Malay Muslim scholars, Singapore: ISEAS, 1983.)

These Malay texts appear to be almost literal translations and adaptations of a medieval Arabic text that was widely known across the Muslim world, from Morocco to Indonesia, Daqā’iq al-Akhbār Fi Dhikr al-Janna wa-l-Nār (‘Particularities from the Traditions about Heaven and Hell’), attributed to one `Abd al-Raḥīm b. Aḥmad al-Qāḍī. This is how it begins:

“God created a tree with four branches and named it the Tree of Certainty. Then God created the Light of Muhammad (upon whom be peace) in a veil of white pearl, and its shape was like that of the peacock. And He placed it on this tree, where it praised Him for seventy thousand years. Then God created the Mirror of Shame and placed it in front [of the Peacock], and looking in the mirror the Peacock saw it was very beautiful. Feeling ashamed before God, it prostrated itself five times – which is the origin of the five prayers that are obligatory for us. (…) And it sweated. From the drops of sweat from its head, He created the angels; from the sweat of its face, the Throne and the Chair, the Tablet and the Pen, Heaven and Hell, the sun, moon and stars, the Veil and all that is in the heavens; from the sweat of its breast the prophets and scholars and martyrs and the virtuous … “

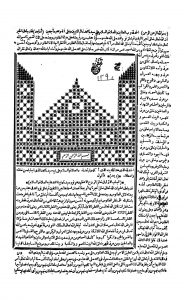

The first page of the Arabic Daqa’iq al-Akhbar, reprinted in Indonesia or Malaysia

In Cikoang’s Mawlid festival, the Peacock, or Muhammadan Light, is represented by an offering of chickens symbolizing beauty and purity, as well as by the colourful decoration of all offerings.

Kandawari with offerings. An illustration from Muhammad Adlin Sila’s doctoral dissertation on the Maulid of Cikoang (Maudu’: A Way of Union with God, Canberra: ANU Press, 2015).

The tree and peacock in this Islamic creation myth echo ancient myths of cosmic trees and cosmic birds that were current all over West Asia, and of which we find survivals in popular religion today. In the myth of Murugan’s struggle with the demon Surapadman, who took the shape of a huge tree standing in the middle of the ocean, was split in two by a blow of Murugan’s sacred Vel, after which the halves, in the shape of a peacock and a rooster, could be subdued by the deity (see the 4th instalment of this peacock blog), we may perhaps recognize the same primeval tree and peacock, although the myth is embedded in another context.

As I was reflecting about the surprising similarity of South Indian peacock lamps and the Yezidi sanjaq, various myths and rituals with peacocks that I had encountered over the years came back to mind. I recalled that I had wondered whether there could be a connection between those semi-divine peacocks and the Yezidis’ Peacock Angel. Digging up my old notebooks, I recovered the notes summarised above. Besides these, I remembered having been struck by peacock figurines in yet another religious context, the Muharram processions in Iran, and I knew I must have photographed some.

On the 10th of the Islamic month Muharram, the day on which Shi`is commemorate the martyrdom of the Imam Husayn, the mourning processions in Iran featured large structures (called `alam, standard) decorated with numerous symbolic figures including peacocks. Here is one that I photographed in Kermanshah in 1975. The peacocks are very recognisable (and so are the serpents, to which I shall return later).

Part of the horizontal beam of a large `alam, with various symbolic figurines

(Kermanshah, 1975)

The same `alam in the Muharram procession. Kermanshah, 1975

There is some literature on these standards, which also mentions the peacocks, but I have not found any explanation of what that bird might symbolise in this context. Could it perhaps be that the `alam represents the cosmic tree and the peacock the Muhammadan Light, and that we have here a representation of the same creation myth?