Qatar Insights Series – A Note from the Editorial Team

Trade and investment links between Qatar and countries in East and Southeast Asia have been steadily expanding in recent years. This trend is likely to intensify in the next decades as the fast-growing economies of Asia will require more hydrocarbons from the Middle East.

The Qatar Insights Series is designed to give readers in Asia a broader perspective of Qatar beyond the Arab boycott of the tiny emirate that has dominated Gulf news headlines the past nine months.

In this first Insight piece, Simona Azzali and Mattia Tomba describe the urban planning process and the construction sector in the Qatari capital Doha, with particular reference to the spatial and social fragmentation of the city. Highlighting the lack of coordination among the entities involved in the planning process, the proliferation of mega projects, and the role of sports in urban planning, the authors look at the Qatari government’s recent push for a more sustainable urban development.

By Simona Azzali & Mattia Tomba

Introduction

Since the 1990s, the Gulf region has experienced unprecedented economic development, along with rapid urban growth and motorisation. Together, this has created new social and business opportunities for the local populations but also important challenges for the local governments, especially with regard to sustainable development. Urban sprawl, lack of planning, harsh weather conditions, the absence of pedestrian walkways, and — until now — an absence of public transport are among the main problems that some of the major Gulf cities face. Doha, in particular, has almost quadrupled in terms of population size over the past two decades, growing from around 450,000 people in 1995 to almost 2 million today.[1] This rapid population expansion has led to a vast urban growth, with the construction of new neighbourhoods, shopping malls, and other amenities, and completely reshaped the city.

This article aims to describe the urban planning processes and the construction sector in Qatar’s capital city. It looks at Doha’s planning management and briefly explains some of the links between the oil and gas and the real estate sectors. It highlights the lack of sustainable planning practices, noting that construction in the city is characterised by the proliferation of mega-projects and the role of sports in the planning process. The article then looks at the social and spatial fragmentation of the city and concludes with recommendations for policy changes.

Doha and the Gulf Cities: Urban Form, City Development, Planning Process

Since the 1970s, the Arabian peninsula has changed dramatically as its cities developed and formed a new, distinctive city type. Sulayman Khalaf, in his 2006 essay “Evolution of the Gulf City Type, Oil, and Globalization”, theorises that the urban centres of the Persian Gulf are all characterised by coastal location, exponential growth, a multi-ethnic migrant character, and car-based models with limited or near absent public transport.[2] But the Gulf cities also share other features such as urban sprawl and low population density owing to the proliferation of areas with a single land use. Additionally, with the aim of rebranding their image internationally and modernising and beautifying their centres, Gulf municipalities are investing heavily in mega-projects such as five-star hotels, high-rise towers, and shopping malls. The result is that the physical appearance of the new Gulf cities is a metaphoric display of large cases of goods.[3]

The economic model of the Gulf countries is still mainly based on natural resources. Oil and gas revenues are used to cover the state’s budgets and are invested into infrastructure projects aimed at improving the quality of life of their citizens and serve as a tool to redistribute wealth. These infrastructure investments include road, power supply, transport, school, hospital, and telecommunication projects. Any unspent revenue goes to the central banks and sovereign wealth funds that invest the money to stabilise the economy against potential macroeconomics shocks and also generate returns for future generations. The main limitation of this economic model is its high exposure to the volatility of oil and gas prices. Indeed, the drop in energy prices since 2014 has caused the deterioration of fiscal and external balances and a slowdown in the economic growth of the Gulf countries.

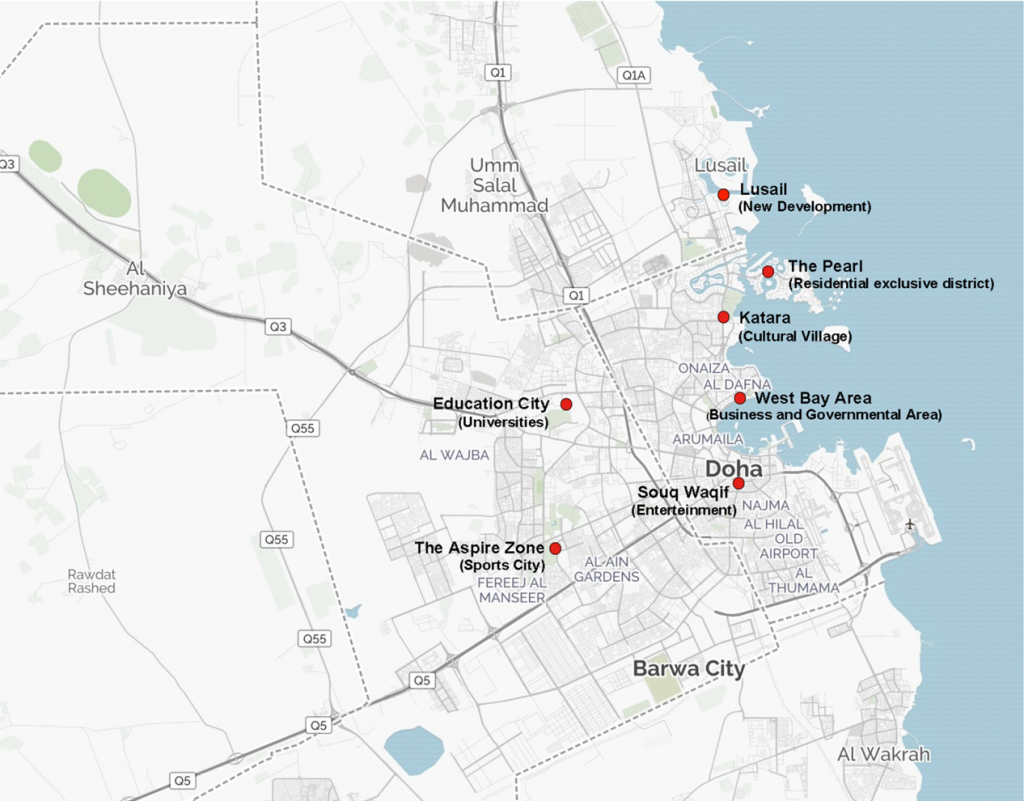

Doha is a young, rich, and booming city that is struggling to manage its rapid urban development and planning system. The speed and intensity of this growth has led to a massive fragmentation, not only in spatial terms, but also social and managerial.[4] From a spatial point of view, Doha, like other oil cities, is made up of urban clusters.[5] It is a city of islands, characterised by many polycentric centralities — isolated zones and neighbourhoods — that are not connected to each other and are experiencing extremely rapid horizontal growth. Its rapid expansion, accompanied by a lack of strategic vision and a comprehensive master plan, has led to the development of a cluster of themed islands, creating a fragmented and dispersed urban fabric. Indeed, each district has a dedicated function, and mixed-use areas are extremely limited. Figure 1 shows the massive zoning of Doha and how the city is segmented into themed areas (Aspire the sports district; Education City, the research centre housing all the university campuses; Souq Waqif, an area dedicated to leisure; Katara, the cultural district; and West Bay, the business centre). This phenomenon of polarisation, or clustering, is accompanied by some functional issues, which are emblematic of all Gulf cities: scarcity of parking areas and alternative streets, traffic congestion, and pollution. Another issue relates to the durability and low quality of the buildings. Harsh weather conditions, with temperatures up to 50°C for many months of the year, unskilled manpower, the use of sub-standard building materials, and lack of maintenance are some of the factors behind the deterioration of the majority of the buildings after only a few years. An example is the exclusive residential district of The Pearl in the north of Doha, which opened in 2009 (see Figure 1). Since 2013, many tenants of this luxury development have complained about mould on the walls, air conditioning problems, water shortages, leaks, and other plumbing issues.[6] The same fate affects the majority of the towers in the West Bay area, the business district of the city (Figure 1). Also, malls, homes, and roads flood every time it rains, causing road closures, ceiling collapses, and leaks. In 2015, even Doha’s newly opened Hamad International Airport faced several issues after heavy rain.[7]

Figure 1

The city of Doha: selected current and future mega-projects.[8]

Likewise, Doha is socially fragmented. Being Qatar’s major urban centre, it is a multi-ethnic city with inhabitants of more than 100 different nationalities. It is home to a large community of expatriates, primarily from India (545,000 residents), Nepal (400,000 residents), the Philippines (200,000 residents), and Egypt (180,000 residents).[9] Doha has the world’s highest ratio of migrants to citizens: foreigners make up around 86 per cent of the city’s overall population, while the number of Qatari nationals is about 300,000.[10] This stratification is reflected in the way the city is developed, particularly in the types of housing, which vary according to nationality and income. Qatari nationals usually live in huge and expensive villas at the northern or western edges of the city, high-income expatriates are accommodated in comfortable apartments in gated compounds or towers, situated in more central areas, while low-income groups, usually from Southeast Asia, live in residential camps and ad hoc shanty housing compounds in the southern suburbs of the city or in the poor, old quarters of downtown Doha.[11] The commodification of public spaces is another characteristic of this segregation, with the city’s rapidly proliferating shopping malls being effectively off limits to low-income foreign labourers. In fact, the Central Municipal Council introduced a regulation to limit access to these privately-owned public spaces to nationals and the high-income strata of the population through the introduction of family-only days, which discriminates against foreign labourers who are bachelors or who have left their families behind in their native lands.[12] Indeed, it is not unusual to spot armed security guards at these spaces firmly escorting those of South Asian appearance towards the exits. Parks or other open air public spaces are scattered around the peripheries, disconnected, and too limited in number to serve the needs of the growing population. Often, parks are also inaccessible to low-income migrants as there are no public transport options to access them.

The planning management of Doha is fragmented, and the rapid urbanisation and growth of the city took place without a comprehensive master plan. As Khaled Adham explains,[13] priority in city planning was given to facilitating the daily use of private cars by large numbers of individual commuters. Indeed, until now, greater attention is paid to building first-class road systems that fragment and divide the city instead of creating integrated neighbourhoods. Big highways of four to six lanes literally cut the city and make it impossible to move on foot or by bicycle from one district to another, and even within the same neighbourhood. Additionally, the city has not been developed in a compact fashion, and the distance among the various districts is considerable, making it necessary to move by car.

The city’s master planning has been focused on the development of mega-projects and forms of spectacularisation. With the aim of transforming Doha into an international service hub, the Qatari government has drastically transformed its urban policy process, shifting from an administration characterised by a high level of centralisation to a decentralised system that does not follow a consistent decision-making process but instead makes decisions on a case-by-case basis,[14] according to the type of project, its location, and its financier. The launch of several huge publicly funded urban developments amidst this decentralisation of decision-making has led to a lack of communication and coordination among the many agencies and stakeholders involved in the design and construction of a mega-project, resulting in a duplication of efforts. Also, the planning practice in the Gulf is completely dependent on foreign companies and professionals. The master planning is usually sub-contracted to international consultancy firms, while the implementation is carried out by local government entities,[15] with overlaps of roles and functions. In addition, the lack of locally trained planning professionals, as well as the failure to consult the public or even local professional associations, generates a dependency on foreign consultants that results in a shallow understanding of the local specificities (e.g., local culture and needs, and budget constraints).

Qatar’s National Vision 2030

In an effort to manage the problems outlined above and shift to a more sustainable urban form, the Qatari government in 2008 introduced a comprehensive blueprint with ambitious strategies related to the development of its environment, society, and the economy. This programme, called Qatar National Vision 2030 (QNV 2030), will play a major role in developing and improving Doha’s urban governance in the coming years. Its implementation consists of the design and realisation of a comprehensive master plan, which is required to guide Doha’s urban development towards more consolidated structures.[16] QNV 2030 will allow the country to reach its long-term goals and to implement a framework for developing its major strategies, which include the adoption of a sustainable policy with regard to urban expansion and population distribution, the development of a world-class infrastructural backbone, and the implementation of reasonable and sustained strategies that secure a high standard of living for the current generation and future generations.[17] In this context, sports, and particularly the 2022 FIFA World Cup, is meant to facilitate the implementation of this ambitious programme by catalysing important infrastructure, such as the transport system, and promoting healthy lifestyles through sport. In this sense, the World Cup tournament can contribute to the spatial integration of new neighbourhoods in the city.

In line with the government’s vision, the city is characterised by a phenomenon of massive sportification.[18] For the past ten years, Doha has been trying to transform itself into an international sporting hub. Since 2006, when it hosted the Asian Games, the city has staged several international tournaments, and its hosting of the 2022 World Cup will be a first for the Middle East. A Sport Day, the second Tuesday of February, was introduced as a national holiday in 2012, and sports tourism is flagged by QNV 2030 as an example of economic diversification from the oil-based model. Sports is also considered a way of improving the quality of life of Qataris by encouraging a more active lifestyle.[19] Massive planning efforts and new venues and infrastructure have been built to host events. One example is the Aspire Zone, or Doha Sports City, a complex of about 2.4 sq km, constructed on the occasion of the 2006 Asian Games. Major sports infrastructure will be built in the coming years to comply with the requirements of the World Cup. Qatar’s Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy has scheduled the construction of eight new stadiums and developed a new mobility plan, including the building of transport infrastructure such as a new port, a new metro system, and the recently opened Hamad International Airport. The Qatar Government estimated that the country will spend over US$140 billion in mobility and transportation infrastructure, most notably the Doha metro system,[20] which will be operational by the 2022 World Cup. Consisting of four lines, the metro will be underground in the city centre and elevated at the periphery. For the tournament, six stadiums out of eight will be accessible by the new metro system, new roads will be built, and many existing roads upgraded. After the tournament, movement in and out of Doha will be easier, and the physical and social fragmentation of the city may be partially mitigated.

Policy Recommendations

Since the 1950s, with the decline of the Modern Movement of architecture, urban planners, architects, and municipalities have tended to support the adoption of strategies that promote medium–high population density, mixed-use neighbourhoods, and compact cities. Indeed, it is believed that these policies can encourage the development of healthier and more sustainable cities by reducing the need for car travel and increasing local self-sufficiency.

To shift from the “islands within islands” model to the development of compact, mixed-used neighbourhoods and districts, Gulf cities such as Doha should firstly integrate land-use policies with transport planning strategies. Transport Oriented Development (TOD) projects worldwide tend to promote a mix of housing, retail, services, workplaces, and open spaces within walking distance of transit systems, and they maximise transit use. Mixing land use can dramatically reduce distances and fragmentation while also increasing the adoption of non-motorised modes of travel, particularly for shopping and recreational trips.[21]

Secondly, it is important to introduce more mass transit options and a multi-modal approach that facilitates the shift from one option to another. Non-motorised modes (e.g., cycling and walking) are important and need to be promoted and implemented. Along with the Doha metro system, alternatives such as cycling have seen recent progress in Doha. In 2015, Asghal, Qatar’s public works authority, opened a new 22-km cycling road running from the west Barwa City development to Al Matar Street in the south of Doha. Also, Ashgal announced that it would include cycling lanes in all future road projects.[22] These options will contribute to mitigating social segregation and inequality and will increase accessibility and mobility for all residents.

Lastly, there is a need to build capacity among local planners. In this respect, the Qatari government should ensure the dissemination of best practices and planning knowledge among architects, designers, and planners working in the region. Qatar University founded the country’s first Department of Architecture and Urban Planning in 2009, and the first students in these disciplines have graduated recently. The establishment of such a study programme is a fundamental step in building planning capacity in the country and training locally educated designers and planners.

Simona Azzali is currently a researcher in urban studies at the Dept. of Architcture, NUS. She holds a PhD in Urban Planning and Design from Qatar University/University College London and BSc and MSc degrees in Design from Politecnico di Milano. Her academic interests are primarily related to Doha and other cities in the Gulf region, sustainable urbanism, mega-events and their impact on the built environment, and urban regeneration. She has also been active in design consultancy since 2000.

Mattia Tomba is a senior research fellow at the Middle East Institute, NUS. He is a multi-disciplinary investment professional with a track record of investments and acquisitions in different asset classes, sectors, and geographic areas. Mattia previously worked for Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund (Qatari Diar), Goldman Sachs Group (Whitehall Real Estate Funds), and Merrill Lynch. He graduated from the Fletcher School at Tufts University (Boston) with a MA in International Affairs and from Bocconi University (Milan)/Science Po (Paris) with a BS in Business Administration. Mattia also sits on the Advisory Council of the Center for Sovereign Wealth and Global Capital at the Fletcher School.

[1] Qatar Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. 2016 (Population section). https://www.mdps.gov.qa/en/statistics/Statistical%20Releases/Population/Population/2016/Population_social_1_2016_AE.pdf.

[2] Sulayman Khalaf. “Evolution of the Gulf City: type, oil, and globalization,” in Globalization and the Gulf, ed. J.W. Fox, N. Mourtada-Sabbah and M. al Mutawa, (New York: Routledge, 2006), 244-265.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Simona Azzali, “Mega-events and urban planning: Doha as a case study,” Urban Design International 22, no. 1 (2017): 3-12.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “Luxury towers in Qatar suffer quality issues due to cost-cutting, deadlines,” Doha News, October 4, 2013. https://dohanews.co/luxury-towers-in-qatar-suffer-quality-issues-due-to.

[7] “Malls, roads, and homes flood after heavy Qatar rain,” Doha News, November 26, 2016. https://dohanews.co/villaggio-mall-springs-leaks-heavy-qatar-rain.

[8] Simona Azzali,“Mega-events and urban planning: Doha as a case study,” Urban Design International 22, no. 1 (2017): 3-12.

[9] Jure Snoj, “Population of Qatar by nationality,” BQ Doha, December 18, 2013. http://www.bq-magazine.com/economy/2013/12/population-qatar.

[10] “Qatar in Figures, 2017,” Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics, March 14, 2018. https://www.mdps.gov.qa/en/statistics/Statistical%20Releases/General/QIF/Qatar_in_Figures_32_2017_EN.pdf.

[11] Simona Azzali, “The Impact of Rapid Motorization and Urban Growth: An Analysis of the City of Doha, Qatar,” The Arab World Geographer 18, no. 4 (2015): 299-309.

[12] Heba Fahmy, “CMC calls on Qatar’s malls to revive ‘family day’ policy,” Doha News, November 17, 2015. https://dohanews.co/cmc-calls-on-qatars-malls-to-revive-family-day-policy/

[13] Khlaed Adham, “Rediscovering the island: Doha’s urbanity from pearls to spectacle.” in The evolving Arab city: Tradition, modernity and urban development, ed. Y. Elsheshtawy (New York: Routledge, 2008), 218–57.

[14] Ashraf M. Salama, and Florian Wiedmann, “Demystifying Doha: On Architecture and Urbanism in an Emerging City” (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2013).

[15] Agatino Rizzo, “Rapid urban development and national master planning in Arab Gulf countries. Qatar as a case study,” Cities 39 (2014): 50–57.

[16] Qatar General Secretariat of Development Planning, “Qatar National Vision 2030: Advancing sustainable development, Qatar’s second human development report,” (Doha: Gulf Publishing and Printing, 2009).

[17] Ibid.

[18] Mahfoud Amara, M, “2006 Qatar Asian Games: A ’modernization’ project,” Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics 8, NO. 3 (2005):493–514.

[19] Qatar General Secretariat of Development Planning, “Qatar National Vision 2030: Advancing sustainable development, Qatar’s second human development report,” (Doha: Gulf Publishing and Printing, 2009).

[20] Oxford Business Group, The report: Qatar 2014 (Oxford, 2014).

[21] Susan L. Handy, and Kelly J. Clifton, “Local shopping as a strategy for reducing automobile travel,” Transportation 28, no. 4 (2001):317–46.

Assad J. Khattak, and Daniel Rodriguez, “Travel behaviour in neo-traditional neighbourhood developments: A case study in USA,” Transportation Research Part A 39, no. 6 (2005): 481–500.

[22] Oxford Business Group, 2015. The report: Qatar 2015. (Oxford, 2015).