Introduction

Since 2000, there have been growing interactions between China and the Gulf Cooperative Council (GCC), especially in the economic field. This relationship was cemented on China’s growing oil demands and boosted by China’s going-out strategy. The attack on the World Trade Centre in New York on 11 September 2001 and the aftermath of the Iraqi invasion in 2003 have transformed the geo-political and geoeconomic balance in the Gulf. On the Gulf side, frequent visits of high-level Gulf officials to China suggest that there are growing signals of seeking for a new strategic partner to offset the US influence, by ‘looking east’. China has become an important alterative. One notable visit was that of King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia in 2006 when he made China his first overseas destination after his coronation. On the Chinese side, the government is aware the significance of the Gulf from the energy supply perspective, as well as its geo-implications. China’s growing presence in the Middle East has alarmed the West.

This essay attempts to examine whether China’s primary interest in the Gulf is oil or beyond; and the factors that determine China’s Gulf policies.

There are four sections in this essay. The first section briefly traces the historical relationship of China and the GCC. The second section analyses whether China’s primary interest in the region is economic. The third section identifies the main factors that may affect China-GCC relationship beyond energy. The final section concludes with some recommendations for a deeper bilateral relationship in the future.

History of China and the GCC

Unlike the relationship with Iran and Iraq, China’s relations with the GCC is relatively new because most of the GCC member states were established in the late 1960s and the early 1970s. Moreover, the GCC was formally established only in 1981. Thus, the relationship between China and the Gulf should be examined at two levels – at the institutional level (China and the GCC) and at the country level (China and each member state of the GCC).

Political Relations – China and the GCC

At the institutional level, then Foreign Minister of China, Huang Hua, sent a telegram of congratulations to the Secretary General of the GCC two days after the establishment of the GCC in 1981. Formal ties have been established since. There was, however, not much contact between China and the GCC during the 1980s, unlike links between China and the individual member countries of the GCC. (This will be discussed in the following section.) In 1990, formal mechanisms of regular meetings at high level were established. Since then, regular meetings have been held annually between the Foreign Ministers or their representatives and the Secretary General of the GCC at the UN General Assembly in New York. In 1996, a regular consultative mechanism was introduced under which both parties take turns to hold annual meetings on political and economic issues in Beijing and Riyadh respectively.

The other formal mechanism for political consultations is through the China-Arab Cooperation Forum established in 2004. Being the members of the League of Arab States, the Forum is yet another platform for the GCC countries and China to interact, especially on political issues.

However, it would appear that the formal mechanisms mentioned above are not as effective as they ought to be. Chinese scholars are of the view that in general there continues to be a big gap in mutual understanding because the Arab World often obtains its information on China through a third party—the Western media. Chinese scholars who were abroad for conferences or academic exchanges found that some key concepts of China’s foreign policy, such as the concept of Harmonious World, did not come across to their Arab counterparts. This was highlighted in a statement by Qian Xiaoqian, the Vice-Minister of the State Council Information Office, at the Forum of China-Arab Cooperation in Media in April 2008:

“Compared with other aspects of China-Arab relations, especially the polity and economy states, the communion of media between China and Arabia lag. There are only a few reports about the development of Chinese-Arabic relations, reflecting the positive and significant changes in various sides of people’s lives. The news about history, culture and even the travel industries both in China and Arabic countries remains infrequent as well. This does nothing but baffle the sense of understanding between Chinese and Arabs. We should struggle together to change this situation. Since the media are considered an important bridge to enhance understanding, the Chinese and Arabic media should play a significant role and assume a more positive function to take this responsibility.”[1]

Political Relations – China and Member States of the GCC

At the individual country level, the state of bilateral relations between China and the member states of the GCC is more complex. The sequence in the establishment of diplomatic relationship between China and each GCC country demonstrates significant changes in China’s policy.

Before the 1970s, China’s engagement with the GCC member states was mainly dominated by ideological orientation. With the deteriorating relations between China and the Soviet in the 1970s, Soviet penetration into the region became the priority factor for China in its relations with the GCC. Kuwait, for example, established diplomatic relationship with China in 1971. In the following years, China-Kuwait relations were bolstered by Kuwait’s support of China’s admission to the UN. Likewise, China-Oman relations demonstrated the evolving pragmatic side of China’s foreign policy. It moved away from its earlier stance of supporting Oman’s rebellion group in the 1960s to establishing diplomatic relation with Oman in 1978.

In the 1980s, China established diplomatic ties with other smaller states in the Gulf, including the UAE in 1984, Qatar in 1988 and Bahrain in 1989. Yet, it was not until 1990 that China established diplomatic relationship with the regional power, Saudi Arabia. According to Huwaidin[2] (2002, pp 213-236), this final formalisation of bilateral relations resulted from the following initiatives – supporting the Chinese Muslims to the Hajj, sending Muslim scholars abroad to attend various Islamic conferences at different levels, dispatching business delegations to Riyadh and selling missiles.

Despite the delayed diplomatic establishment, China and Saudi relations have been strong in both political and economic spheres ever since. When President Hu Jintao visited Riyadh for the first time in 2006, the two countries reached consensus in establishing “strategic friendly relations”. When China was struck by a severe earthquake in May 2008, Saudi Arabia donated US$60 million to the stricken areas, becoming the largest donor to the Chinese government. This certainly played a positive role in bilateral relations. One month after the earthquake, President Xi Jinping, the Vice President of the PRC, visited the Saudi Arabia and signed The Joint Statement of the PRC and the Saudi Arabia on Strengthening Cooperation and Strategic Friendly Relations[3]. Six months later, in January 2009 President Hu Jintao made another trip to Riyadh, his second in three years.

From 1990s onwards, relations between China and the member states of the GCC grew rapidly all round, boosting economic relations and strengthening political relations. In 1993, China became a net oil importer, and that drove China to secure reliable oil suppliers worldwide. The Gulf became an important destination for China’s officials.

As Harrison[4] points out:

“In late June and early July 1993 one of the most important developments of 1990s Sino-Gulf relations occurred with the eighteen day tour of all the GCC states and Iran by the Chinese Deputy Premier Li Lanqing…Li came with one purpose—to secure direct oil purchased from the Gulf.”

Oman successfully became the main oil supplier for China. According to Huwaidin (2002, p 210):

“…in 1993, it (Oman) immediately assumed a leading position…Its (China’s) imports of Oman’s crude oil continued to increase every year after 1995, which allowed China to become the third largest recipient of crude oil from Oman in 1997.”

Energy cooperation between China and Saudi Arabia also experienced significant growth. Saudi-invested projects in China currently totalled at approximately US$5.6 billion[5].

Economic Relations

Trade relations became a dominant issue since 1990. It was driven by China’s accelerating demands for oil to ensure its rapid growth. At the institutional level, China and the GCC signed the Framework Agreement on Economic, Trade, Investment and Technological Cooperation. At the individual state level, bilateral agreements covered issues, such as avoidance of double taxation and the prevention of fiscal evasion, the promotion and protection of investment, economic, trade and technological cooperation and so on.

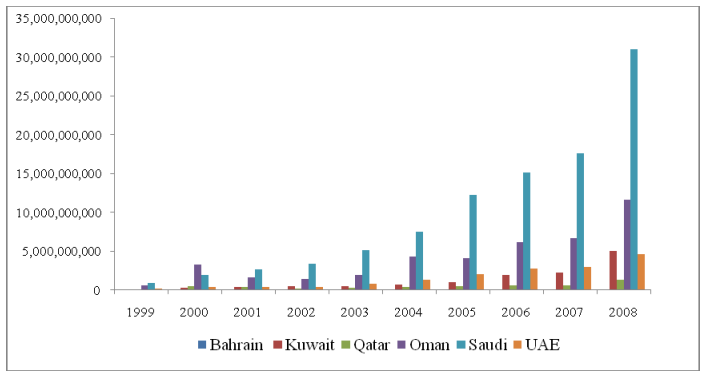

Trade statistics[6] shows that GCC export to China was valued at US$655 million in 1993. By 2000, it jumped to US$6.4 billion. Although there is no accurate figure available on the volume of Gulf oil exported to China, trade between China and the two main oil exporting countries in the Gulf – Oman and Saudi Arabia – may shed some light on the growth of bilateral trade. Oman’s export to China was valued at US$373 million in 1992, which accounted for 6.8 percent of Oman’s total export. This figure jumped to US$12.6 billion in 2008. Meanwhile, Saudi exports to China accelerated from US$68 million in 1993 to US$ 2 billion in 2000, reaching to approximately US$ 31 billion in 2008.

Figure1 China Imports from GCC

Driven by strong economic growth in the 1990s, the Chinese government launched the ‘going-out’ strategy to encourage domestic enterprises to expand to overseas markets. The ‘going-out’ strategy and the market size of the Gulf and its littoral region are the other factors in boosting bilateral trade volume. Since the 1990s, the UAE became the prime location for China’s manufactured products to be re-exported to the neighbouring countries. The UAE’s import from China increased from US$2.1 billion in 2000 to US$24 billion in 2008 approximately.[7] As for the trade structure, oil, nature gas and chemical products are the main products flowing from the GCC to China, whilst China mainly exported garments, fabrics, electronic and telecommunication facilities to the GCC.

Figure 2 China Exports to GCC

China-GCC FTA Negotiations

From 1999 to 2004, the two-way trade between China and the GCC grew at an annual rate of 40 percent.[8] The strong growth of bilateral trade encouraged the governments to upgrade bilateral ties. In April 2004, the Secretary General of the GCC and the six Finance Ministers of the GCC states made a joint visit to Beijing. They met with Premier Wen Jiabao and their Chinese counterparts. After the meeting, both parties released a Joint Press Communiqué and signed the Framework Agreement on Economic, Trade, Investment and Technological Cooperation between the People’s Republic of China and the Member States of the GCC. Most importantly, both sides agreed to launch FTA talks. The Communiqué states:

“In order to encourage and facilitate flow of commodities and services between the two sides, they agree to launch negotiations on China-GCC free trade area so as to develop and strengthen relations between China and the GCC member states and create a good foundation and environment for mutual investment between the two sides in various economic areas.”9

To both China and the GCC, the political implications of the FTA were reflected in two major areas. One was to diversify oil-import sources/export destinations. The other was to balance US dominance of the region. After 9/11, the GCC leaders felt an urgent need to reduce US presence in the region. Thus, what emerged was that the GCC states tended to seek alternatives in the East. As Harrison (2006, p 299) states, “…the GCC states in particular repeatedly urged Beijing to take a more active role in Middle Eastern affairs.”

Against this background, the first round of China-GCC FTA negotiation was launched in January 2005. From the outset, the negotiation went well. After the conclusion of the first round, both sides agreed on the work mechanism, subjects for discussions, and to hold a round of negotiations every three months. By the end of the second round, an agreement was reached on the tariff reduction mode of goods trade.10 In April 2006, the third round of negotiations was concluded. After the talks, both sides further narrowed differences on market access, reached a consensus in aspects of the rules of origin, TBT and SPS, and exchanged views on a draft text of an agreement on goods trade in the Area.11

Although negotiations on trade in goods was easily concluded, progress on services was not as smooth.

This difficulty was reflected in a meeting between Sheikha Lubna, then the Minister of Economy and Trade of the UAE, and her Chinese counterpart, Minister Bo Xilai, in late 2006. Sheikha Lubna indicated that there were obstacles that might hinder investors from reaching certain sectors in China, especially in the areas of satellite communications, as such investments faced various procedural restrictions.12 Since then, due to the lack of published information, it is assumed that either progress was not reported or there was not much breakthrough.

10 Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, China and 6 GCC Countries Holding 2nd

Round FTA Negotiation, Retrieved 4 October 2008 from

<http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/aarticle/newsrelease/significantnews/200506/20050600135862.html>. 11 Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, China-GCC FTA Negotiation Making Greater Progress, Retrieved 4 October 2008 from

<http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/aarticle/newsrelease/significantnews/200604/20060401850268.html>.

12 Khaleej times, ‘FTA talks between UAE, China necessary: Lubna’, Khaleej Times, Retrieved 24

January 2008 from

<http://www.khaleejtimes.com/DisplayArticleNew.asp?section=business&xfile=data/business/2006/octo ber/business_october476.xml>.

In February 2008, news was released that the tariff cancellation of petrochemical products and petroleum products was the obstacle in China-GCC talks.[9] Before Sheikh Mohammed visited Beijing and Shanghai in April 2008, the Chinese Ambassador to the UAE, Gao Yusheng, stated:

“The ongoing talks between China and the Gulf Co-operation Council countries on a free trade agreement have been facing difficulties, especially in relation to petrochemical related exports from the UAE, and the effect on some of the major Chinese corporations.”[10]

The China-GCC FTA progressed at a fast pace in the beginning. Yet, the talk was soon grounded on differences in service sectors. The slow progress of the China-GCC FTA talks frustrated those business-oriented ruling elites in the Gulf, who then began to pursue their interests on a country-to-country basis, which seemed to be more effective and efficient.

The UAE took the lead. When Sheikh Mohammed, the Vice President of the UAE and the Ruler of Dubai, visited Beijing and Shanghai in April 2008, several deals were concluded. Emaar singed a MoU with a government agency, the Shanghai China-News Enterprises Development Limited, to explore mixed-used property and infrastructure development in the Chinese cities. Etisalat inked an agreement with Huawei Technologies, China’s biggest telecom-equipment maker.

Shortly after Sheikh Mohammed’s visit, the Qatari Prime Minister also made a visit to China. During his visit, two deals on selling liquefied natural gas (LNG) to China were concluded. One was that “Qatargas will sell 2 million tonnes a year of LNG to CNOOC…from 2009.”[11] The other was that Qatargas agreed to sell 3 million tonnes of

LNG a year to PetroChina from 2011 for 25 years together with Royal Dutch Shell.[12]

Agreements on energy supply between China and Saudi Arabia were signed when President Hu Jintao visited Riyadh in January 2009 for the second time. Moreover, Kuwait closed a deal with the Chinese government to establish a refinery in Quan Zhou. A more recent example is the visit of the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, which has the third largest oil reserves in the Gulf, to Beijing in August 2009. His visit also concluded with agreements on future cooperation, especially on alternative energy.

In summary, the interactions between China and the GCC have not been limited by one pattern. On the economic issues, China and the GCC pursue an institutional framework, especially on the FTA negotiations. Yet, when the leaders recognised the slow progress of institutional engagement, they did not hesitate to pursue one-to-one dialogue, as mentioned above. Political interactions between China and the GCC have been relatively less frequent, leading to the popular query if China’s primary interests in the Gulf are essentially economic or do they go beyond?

China’s Primary Interests in the Gulf: Economic or Beyond?

Researchers and observers speculate that China’s interests in the Gulf could extend beyond economics and energy though China’s primary interests in the short and medium term focus on economic and energy cooperation.

Firstly, economic development has become the central issue since 1979 when the opening-up policy was launched. Thus, the main task of China’s diplomacy was to create a favourable environment to import modern technology for economic development. Although China has increasingly participated in international affairs, economic development remains the primary interest for the government. Even when faced with the financial turbulence which started in the late 2007, the Chinese government and its officials stressed on many occasions that a steady growth of China’s economy was itself a contribution to the world economy. Clearly, domestic development is the first priority for the government. Yet, when the crisis deepened, the Chinese government sent several commercial delegations to Europe and concluded a number of large purchasing contracts.

11

Secondly, China’s foreign policy is prioritised on major powers and neighbouring countries. On the one hand, major powers possess modern and sophisticated technologies that China relies on. On the other hand, China shares borders with 20 other countries (including those on sea). This geostrategic complexity is often cited as an important element in the determination of foreign policies. Thus, to create a favourable environment with neighbours is essential for China’s development. This is clearly evident in the official reports released at the Party Congress, which is held every five years. President Jiang Zemin stated at the 16th Party Congress:

“…continue to improve and develop relations with the developed countries…continue to cement our friendly ties with our neighbours and persist in building a good-neighbourly relationship and partnership with them…continue to enhance our solidarity and cooperation with other third world countries, increase mutual understanding and trust and strengthen mutual help and support…”[13]

Obviously, the developed countries and the neighbouring countries are on China’s top agenda. This policy is being carried into the 17th Party Congress.

Thirdly, multilateral diplomacy becomes an important means for China to participate in regional and international affairs. It provides a new platform of improving China’s diplomatic abilities and enhancing its roles in global issues, including climate change and reforming international institutions, such as the IMF. Over the years, China’s experiences in dealing with ASEAN and WTO reinforced China’s confidence and capacity in tackling regional and international affairs. Recognising the GCC as a successful regional organisation in the war-inflicted Middle East, a conclusion of ChinaGCC FTA agreement would be much welcomed as the second successful regional cooperation on China’s side. This might offer an explanation why China did not react to the GCC-US FTA negotiations as the EU did. China thought that it was an internal matter and would not have negative impact on the China-GCC FTA talks.[14] Of course, the GCC’s determination in taking a collective position on the issue with China in order to obtain a better deal is another factor. What is worth mentioning here is that in tandem with the China-GCC FTA negotiations, GCC also conducted FTA negotiations with Japan, Korea and Australia respectively in a collective manner.

Fourthly, diversifying energy supply source is a primary objective of China’s energy policy. China perceives this as:

“safeguarding energy security, Diversifying energy consumption pattern, diversifying sources of energy, realising high effectiveness of energy exploration, rationalising the protection of energy environment, commercialising energy fields, perfecting energy legalisation.”[15]

While the West felt threatened and emphasised on China’s increasing imports from the Gulf and while the Chinese Minister toured the Gulf countries to secure energy supply in 1993, what is often neglected is that the Chinese oil companies also made investments in Thailand, Indonesia, Canada and Peru in the same year.[16] Gradually, Chinese investments or oil purchase contracts reached Central Asia, Africa and South America. Furthermore, Africa has been the recent source to meet China’s energy demand. The statistics show that Angola replaced Saudi Arabia as China’s biggest oil supplier in March 2008.[17] China’s imports from Sudan increased sharply in 2007 by over 110 percent given the fact that the expansion of the Khartoum Refinery was completed. In the mid-term, oil imports from Sudan are likely to increase further because China is building a new refinery, which is projected to be completed in 2010, 22 aimed to process Sudanese crude oil as well as similar low-sulphur oil from other countries.

Resulting from this diversification, it is estimated that China’s imports from the Gulf region might be reduced in the short term. Nevertheless, it does not mean that the Gulf is no longer significant to China. Instead, it reflects China’s intention of avoiding direct confrontation with the US in the search for reliable energy supplies. In the long run, the

Gulf region will definitely play an increasingly important role in China’s energy supply.

This lies in the hard fact that the proven oil reserves[18] are in this region and account for nearly 62 percent of the total proven oil reserves. By contrast, the oil reserves in Africa contribute to approximately 10 percent of the total reserves in the world.

Finally, most agreements between China and the GCC are related to bilateral trade. There are no agreements on cooperation beyond economics, especially military cooperation. Thus, China has confined its activities to the economic sphere so far. Once China attains more experience and capabilities in dealing with international affairs, China may pursue interests beyond energy and economic cooperation. Then, the key question will be how. Before discussing this question, it is essential to understand the factors which undermine China-GCC relations beyond energy.

Factors Undermining Relations Beyond Energy

The first factor is an internal factor that no agreement has been reached within the

Chinese government of the extent to which China should be involved in the Middle East. Over the years, Middle East did not factor clearly in China’s overall foreign policy. On the one hand, China’s diplomacy has undergone several stages since the country was founded. Through the efforts of three generations of leadership, China’s foreign policy has widened from the ideologically-oriented diplomacy in the 1950s to its current engagement diplomacy. On the other hand, it is genuinely difficult for China to formulate a strategy on the Middle East because of the latter’s complexity and diversity. Firstly, the Arab World does not have a coherent voice. If other regional organisations have worked towards unity, the League of Arab World has seen a process of fragmentation. Its regular meetings have never been fully attended by its members. Secondly, Middle Eastern issues have been intertwined with many complex interests.

They have to be looked into individually.

Moreover, the Middle East had not been a major supporter for China’s return to the United Nations, unlike Africa. Thus, the Middle East does not appear in the articulations of China’s overall foreign policy as often as Africa does. Only recently, it became clear in a strategic report that states (2008, p 38):

“West Asia has become an extension of China’s neighbourhood. China’s major strategic target is to maintain sub-regional peace, participate in the process to solve hotspot issue there, ensure energy security, enhance economic and trade links, and develop its relations with relevant states and organisations in a balanced and all-round way.”[19]

The second factor is the US factor. US has dominated the Gulf for decades since the British withdrawal in the 1970s. As Rahim[20] (2008, p 158) puts it, “…Beijing fears that Washington has already established hegemonic power over the Middle East and might interdict supplies bound from there to China.”

Despite the sour relationship between the Gulf and the US after 9/11, there is a new tendency that suggests the return of Gulf capital to the US. As CNBC Middle East confirms, “Sovereign Wealth Funds in the GCC are taking a wait-and-see approach to an unstable US asset market, but fundamental enthusiasm for US corporate will continue in the medium to long term…” 26 This is mainly due to the weak legal framework for foreign investments in China.

The absence of direct communication could be the third factor undermining China-GCC relationship going beyond energy. Unlike the West, there are very few Chinese experts in the Gulf. There are also few exchange students from the Gulf to China. In 2007, there were 360 Gulf students in China.[21] By comparison, the Chinese universities host 14,758 American students, 4,698 French students, 3,554 German students and 2,077 British students. Given this, the Chinese government held a media conference between China and the Arab world this year as mentioned earlier.

In addition to the traditional geo-political factor, climate change could be the fourth factor forcing China to rationalise its energy structure. It may consequently affect China’s demand for oil imports in the long run.

In the recent years, China felt being ‘attacked’ by the international community. Being one of the fastest growing economies, China’s development has been criticised as hastening climate change. In response, China has intensified its efforts to address the issue. A newly revised Energy Conservation Law was enacted in April 2008. In October 2008, China published its first white paper on climate change, China’s Policies and Actions for Addressing Climate Change, and established some quantitative targets.

According to the paper:

“The energy consumption per-unit GDP is expected to drop by about 20 percent by 2010 compared to that of 2005, …The target by 2010 is to raise the proportion of renewable energy (including large-scale) hydropower in the primary energy supply by up to 10 percent, and the extraction of coalbed gas up to 10 billion cu m.”

In addition, the Chinese government’s promotion system for officials has changed from GDP-linked performance to environment-linked performance. As Article 6 stipulates:

“The State implements the energy conservation target responsibility system and the energy conservation examination system, and takes the completion of energy conservation targets as an item to assess and evaluate the performance of the local people’s government and persons in charge thereof.” [22]

Developing renewable energy has been a primary focus for the Chinese government, which drafted the Eleventh Five-year Plan for Renewable Energy Development [23]. In addition to the guiding principles, the plan indicates the specific sectors for developing renewable energies, which are hydropower, biofuels, wind power, solar power and renewable energies in villages. Renewable energy accounts for a significant part of the 4-trillion-yuan stimulus package released by the Chinese government in order to combat the global economic recession. It is planned that 350 billion yuan, or 9 percent of the total, would be invested in the sustainable environment sector. [24] Thus, all these measures and serious efforts of rationalising energy structure will affect China’s oil imports in the long term.

In summary, China’s near-term engagement with the region is at the economic level. Although China’s increasing engagements in international affairs, such as G20, requires it to take on growing responsibilities, its capacity for handling international affairs has been relatively limited. Its near-term priority will be domestic issues and its relations with neighbouring countries.

Recommendations

The following measures are suggested for a more sustainable bilateral relationship between China and the GCC:

- Remove barriers of the FTA and conclude the FTA as soon as possible.

China should establish a committee to coordinate with relevant parties in China to conclude the FTA soon. Meanwhile, the GCC has to reach an agreement on the sectors that may hinder the FTA negotiation process.

- China should publish a policy paper on the region.

Releasing this paper either in an official or semi-official form could enhance transparency and predictability, and promote concerted and coordinated initiatives on regional issues.

- Establish exchange programme for students and scholars to promote mutual understanding.

This is a way of cutting the intermediary channel to obtain first-hand information about one another.

[1] Wang, Hongjiang, ‘Promoting Media ties with the Arab World’, Xinhua New Agency, Retrieved 3 October 2008 from <http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2008-04/26content_8053892.htm>.

3

[2] Bin Huwaidin, Mohammed, China’s Relations with Arabia and the Gulf 1949-1999, London, RoutlodgeCurzon, 2002.

[3] The statement is translated from Chinese into English. Not Official translation, Retrieved 4 October 2008 from <http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/chn/pds/gjhdq/gj/yz/1206_27/sbgx/>.

4

[4] Harrison, Martin, Relations between the Gulf Oil Monarchies and the People’s Republic of China (1971-2005), [Unpublished PhD Thesis] Lancaster University, 2006.

[5] The value is compiled from various sources of announcements when the contract was signed.

[6] Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, Retrieved 4 October 2008 from

6

[7] Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, Retrieved 4 October 2008 from <www.mofcom.gov.cn >.

[8] Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, China and 6 GCC Countries Holding 2nd

Round FTA Negotiation, Retrieved 4 October 2008 from

<http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/aarticle/newsrelease/significantnews/200506/20050600135862.html>. 9 The Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in New Zealand, The Joint Press Communiqué Between the People’s Republic of China and The Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (GCC), Retrieved 29 September 2008 from < http://nz.china-embassy.org/eng/xw/t142542.htm>.

[9] Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, Retrieved 22 February 2008 from <http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/aarticle/o/dj/200802/2008205391070.html>.

[10] Elewa, Ahmed A., ‘Mohammed’s visit will give a strong boost to bilateral ties, says ambassador’, Gulf News, Retrieved 31 March 2008 from <http://www.gulfnews.com/business/General/10201755.html>.

[11] Reuters, ‘Qatar in LNG deal with PetroChina, CNOOC’, Khaleej Times, Retreived10 March 2008 from

<http://www.khaleejtimes.com/DisplayArticleNew.asp?xfile=data/business/2008/April/business_April33 2.xml§ion=business&col>.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Xinhua News Agency, Jiang Zemin’s report on the 16th Party Congress, Retrieved 24 January 2008 from <http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2002-11/18/content_633685.htm>.

[14] Al Hakeem, Mariam, ‘Gulf Countries and China to set up Free Zone Area by 2007’, Gulf News, Retrieved 24 January 2008 from< http://archive.gulfnews.com/articles/05/04/25/162260.html>.

[15] Yu,Xiao Feng, ‘Non-Traditional Security and China’, in Wang, Yi Zhou, ed.. Transformation of Foreign Affairs and International Relations in China, 1978-2008, Beijing, Social Sciences Academic Press (China), 2008.

[16] Eurasia Group, China’s Oversea Investments in Oil and Gas Production, Retrieved 7 November 2008 from <http://www.uscc.gov/researchpapers/2006/oil_gas.pdf>.

[17] Zhu, Winnie, Angola Overtakes Saudi Arabia as Biggest Oil Suppliers to China, Retrieved12 October 2008 from< http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601116&sid=aqJ3Wjxs.OWs&refer=africa>. 22 Jakobson, Linda, China’s Africa Policies: Drivers and Constraints—Paper for International Studies Association Convention, San Francisco 26-30.5.2008.

13

[18] OPEC, Annual Statistical Bulletin 2007, Retrieved 7 November 2008 from

<http://www.opec.org/library/Annual%20Statistical%20Bulletin/pdf/ASB2007.pdf>.

14

[19] Cheng, Dongxiao et al, Building up a Cooperative & Co-progressive New Asia: China’s Asia Strategy towards 2020, Shanghai, Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, 2008.

[20] Rahim, Saad, China’s Energy Strategy toward the Middle East, in Collins, Gabriel B, Erickson, Andres S, Glodstein, Lyle J, and Murray, William S, ed., China’s Energy Strategy—The Impact on Beijing’s

Maritime Policies, Annapolis, China’s Maritime Studies Institute and the Naval Institute Press, 2008 26 CNBC, Retrieved 8 October 2008 from <http://gateway.cnbc.com/eng/This-Month/July-2008/SpecialReport1>.

15

[21] Policy Research Bureau, China’s Foreign Affairs 2008 (in Chinese), Beijing, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, 2008.

16

[22] Energy Conservation Law of the People’s Republic of China (Revised in 2007), Retrieved 6 October 2008 from <http://www.lawinfochina.com/law/display.asp?db=1&id=6467 >.

[23] National Development and Reform Commission, The Eleventh Five-Year Development Plan of

Renewable Energy, Retrieved 25 June 2009 from

<http://www.ndrc.gov.cn/nyjt/nyzywx/W020080318390887398136.pdf >.

[24] Caijing, NDRC Gives an In-depth Explanations on the Constituents of 4-trillion Investment, Retrieved 28 November 2008 from <http://www.caijing.com.cn/2008-11-27/110032337.html>.

17