By Nurhidayahti Mohammad Miharja

In December 2012, Prime Minister of Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdogan was reported to have personally shouldered the coffin of a Said Nursi disciple. For the Islamic thinker Nursi, who throughout his life was either exiled or imprisoned even in his death in 1960, his body “was lifted onto an army truck, driven along heavily guarded streets to an airfield outside town, loaded onto a military plane and never seen again”[1] this was clearly a major advance in publicly acknowledging the religious figure and his followers, who in the 1930s were mostly known for being arrested in possession of illegal materials such as books, letters, and prayer caps.[2]

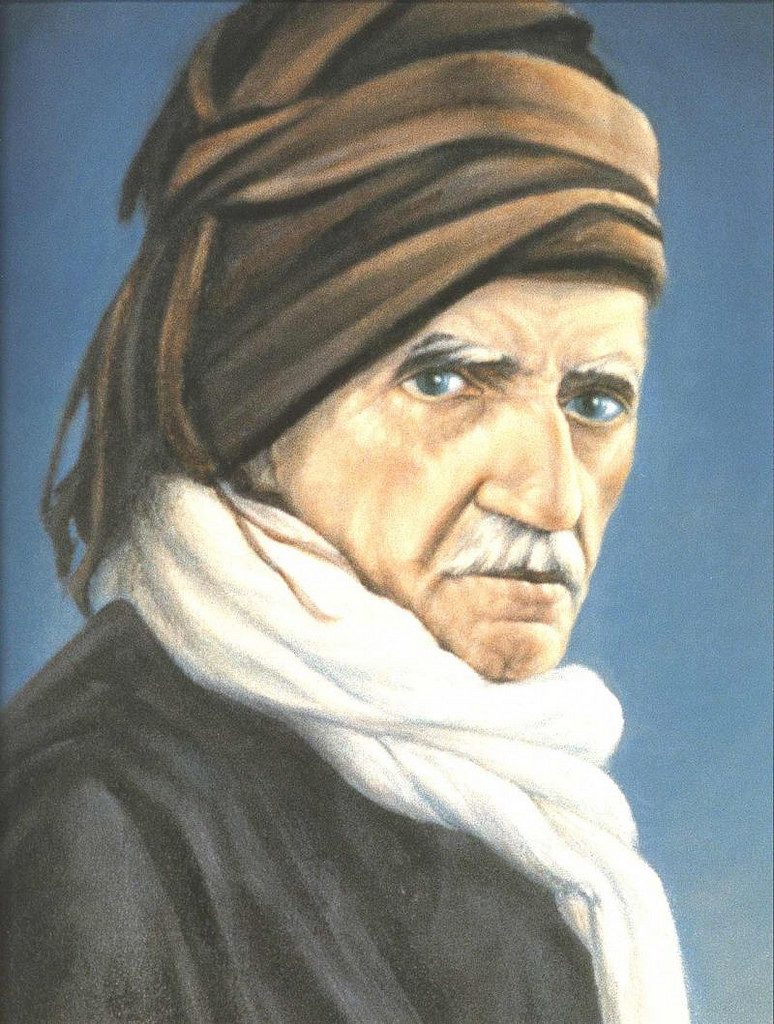

Said Nursi, born in 1876 in a Kurdish village in the eastern Anatolian province of Bitlis, is the author of several volumes of Qur anic exegesis, known as the Risale-i Nur Kiilliyati (The Epistles of Light). They were written in response to Mustafa Kemal Atatrk s militant secularism, which encouraged positivist epistemology and the detachment of religion from public life. Nursi sought to increase religious consciousness in the majority-Muslim country through introducing new understandings of Islam in tandem with the changing world. Continued relevance of the Risale-i Nur has made him famous as the founder of the Nurcu movement, the most powerful text-based faith movement in contemporary Turkey.[3] The broad societal support for Nursi was not acceptable to the pre-Erdogan state that had banned all Sufi orders and other Islamic communities with charismatic leaders since 1924.

Under Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP), Nursi s public profile has recently increased, and positively so. Several legislative changes effected include renaming his birthplace from “Kepirli” to “Nurs,”[4] repealing the ban on Risale-i Nur, which means that it is no longer considered a crime to read his writings,[5] and establishing a parliamentary commission to trace the whereabouts of his remains. These state-led moves have been viewed as part of increased Islamization in Turkey. Yet the widespread equation of an increase in “religiosity” through the increased public visibility of religious symbols with “Islamization” impedes any objective analyses of the increased role of religion in the public sphere. Embrace of Nursi as a religious symbol has been separate from emulating his ideas. This can be seen from the AKP s characteristically defensive religious turned moralizing response to the recent slew of protests in Turkey, which will be discussed later.

If the removal of Nursi s body, which happened six weeks after the Turkish coup d ├®tat in 1960, was motivated by fears that his grave would turn into a shrine of anti-secularism, it would then be more apt to read Nursi s recently increased public profile as part of a desecularization process in Turkish society and politics. Desecularization, as coined by Peter Berger (1999), refers to “the process of counter-secularization, through which religion asserts its societal influence in reaction to previous and/or co-occurring secularizing processes.” It is manifested through a combination of some or all of the following tendencies: (a) a rapprochement between formerly secularized institutions and religious norms, both formal and informal; (b) a resurgence of religious beliefs and practices; and (c) a return of religion to the public sphere.[6] These trends however are not dependent on each other. A greater public role for religion is not necessarily preceded by an increase in the popularity of religion.

In attempts to remove traces of Kemalist secularism, the choice of Nursi is clear to Turkey s AKP Party, because while Nursi succeeds in making religion public, he does so without politicizing religion. Nursi reintroduces religion into the public sphere in a way that focuses on the individual and values rather than politics. While Nursi attributed the problems of Turkey to a moral crisis whose solution required the implementation of shari a, shari a here was to be understood in the ethico-moral sense, furnishing a code of conduct as guide.[7] “Ninety-nine percent of the shari a is concerned with morality, worship, the hereafter, and virtue,” he said. “Only one percent deals with politics; leave that to the rulers.”[8]

Such observations remain applicable for today s Islamist governments, which have found very little in Islam that speaks to the political need for a “modern Islamic state.” The Islamic Republic of Iran, for instance, is not only “a form unknown in Islamic history” but has been described as “much more secular than secular Turkey or many of its Arab neighbors.”[9] Proponents of an Islamic state such as Muhammad Salim al-Awwa argue that the first successful political and legal system of state in the history of mankind that was based on legitimacy and not coercion came from Islam. Therefore, such effective “legal rule” in the past should be revived. Yet, it has been argued that such claims are an incongruous projection of a modern system of government onto Islam s historical governments.[10]

His concern with shari a was thus not reduced to its implementation within an Islamic state; rather, he sought to uphold the overriding aims of shari a (maqasid al-shari ) to preserve life, property, religious freedom, family, and knowledge through individuals. Nursi aimed to reform Turkish society through individuals, whereby Islam was never a political project but a mode of thinking as well as a source of knowledge to achieve a harmonious society while adapting to the realities of modern life. As such, “Islamization” which more often than not erroneously implies an end-aim of establishing a shari a-compliant Islamic state can never be associated with a Nursian endeavor.

The recent embrace of Nursi seems then only natural to assuage charges that Erdogan was headed for an Islamic state. Nursi did not oppose the idea of a secular state, contrary to political Islamists who insist on “Islamization” in many forms.[11] Even then, he never suggested replacing the secular state with an Islamic one[12]. For Nursi, living in a nation-state that did not implement Islamic law did not render anyone any less of a Muslim. He nonetheless expected the secular state to be neutral in terms of respecting the rights and freedoms of various religions: “If you ask me about the secular republic, what I understand by it is that secular (laic) means to be impartial; that is, a government which, in accordance with the principle of freedom of conscience, does not interfere with the religiously-minded and pious, the same as it does not interfere with the irreligious and dissipated.”[13]

This also meant that he was against the very idea of an “Islamic party.” Nursi argued that it was impossible for any one party to represent “true” Islam, as the idea that religion would be identified with a single party was illogical to him.[14] There was also the fear of religious monopoly which could threaten pluralism. For instance, concerns have been voiced about the imposition of a “conservative Sunni morality” by the ruling party with the “recent controversial education reforms that emphasize religious instruction, growing curbs on the sale and use of alcohol, suggested limitations on abortion and public announcements in subway stations to obey the rules of morality. “[15]

In addition to the harsh government s response to its biggest civil unrest which started at Gezi Park[16] last month (May 2013), AKP s embrace of Nursi stops short of the values he stood for towards a more tolerant and inclusive nation. The peaceful sit-in at Gezi Park in May was a last effort to save the last green space in Istanbul s central Taksim Square. The urban redevelopment plans for the area were to include reconstructed Ottoman artillery barracks. The police clampdown on the Gezi Park protests quickly escalated into nationwide demonstrations with citizens of differing political affiliations united against the government s gradual infringement of civil liberties.

Certainly, desecularisation by opening the public sphere to religion does not entail infringing on other secular rights and liberties. Granted, while there is an urgent need to tone down further the connection between religion and politics for Erdogan, whose separation Nursi believed in, these protests however showcase the greater demands of the people which Nursi terms “freedom of conscience.”

Nurhidayahti Mohammad Miharja is a research assistant at the Middle East Institute at NUS. Nurhidayahti Mohammad Miharja holds a BA (Hons) in Sociology and an MA in Arts (Malay Studies) from National University of Singapore. Her research interests include contemporary Muslim thought in Southeast Asia and Turkey, ethno-religious minorities in the Middle East and Muslim civil society.

[1] Susanne Gsten, “Shadow of Military Removed, Turkey Seeks a Spiritual Leader s Remains,” New York Times, 19 December 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/20/world/europe/turkey-seeks-a-spiritual-leaders-secret-grave.html?pagewanted=1&_r=0.

[2] Mustafa Akyol, “Will Turkish Laicite Save The World?” Hrriyet Daily News, 2 August 2012,http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/default.aspx?pageid=438&n=will-turkish-laicite-save-the-world-2010-02-09.

[3] Sukran Vahide, Islam in Modern Turkey: An Intellectual Biography of Bediuzzaman Said Nursi (New York: State University of New York Press, 2005).

[4] “Village Renamed after Islamic Cleric Said Nursi,” Hrriyet Daily News, 3 July 2012,http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/PrintNews.aspx?PageID=383&NID=24624.

[5] Susanne Gsten, “Turkey Plans to Lift Bans on Hundreds of Publications,” New York Times, 12 December 2012,http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/13/world/middleeast/turkey-plans-to-lift-bans-on-hundreds-of-publications.html.

[6] Vyacheslav Karpov, “Desecularisation: A Conceptual Framework,” Journal of Church and State (Spring 2010): 239-240, 250.

[7] Syed Farid Alatas, “Justice, Balance and the Social Order in the Thought of Bediuzzaman Said Nursi,” Nursi Studies,http://nursistudies.com/teblig.php?tno=476.

[8] Sukran Vahide, Islam in Modern Turkey: An Intellectual Biography of Bediuzzaman Said Nursi (New York: State University of New York Press, 2005), 67.

[9] Sami Zubaida, “Islam and Secularization,” Asian Journal of Social Science 33, 3 (2005): 442, 446.

[10] Bassam Tibi, The Challenge of Fundamentalism: Political Islam and the New World Disorder (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998), 102.

[11] An overview of Sharia Law, https://assignmentbro.com/blog/overview-of-sharia-law

[12] Zeynep Akbulut Kuru and Ahmet T. Kuru, “Apolitical Interpretation of Islam: Said Nursi s Faith-based Activism in Comparison with Political Islamism and Sufism,” Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 19, 1 (2008): 102, 104.

[13] Said Nursi, Risale-i Nur: The Rays Collection (Istanbul: S├Âzler Publications, 2006), 386.

[14] M. Hakan Yavuz and John L. Esposito, Turkish Islam and the Secular State (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2003) 12.

[15] “Protests in Turkey: The Straw that Broke the Camel s Back: An Open Letter from Five Concerned Turkish Citizens,” Open Democracy, 3 June 2013. http://www.opendemocracy.net/open-letter-from-five-concerned-turkish-citizens/protests-in-turkey-straw-that-broke-camel%E2%80%99s-back.

[16] “Timeline of Gezi Park Protests,” Hrriyet Daily News, 6 June 2013. http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/timeline-of-gezi-park-protests.aspx?pageID=238&nID=48321&NewsCatID=341.