By Clement M. Henry

I do not think I was one of Zghal’s ‘outrageously na├»ve’ Anglo-Saxon builders of modernization models ‘completely detached from social reality’ (Zghal 1989: 222), but I certainly appreciated his solid grounding in Tunisian realities as well as social theory and his kind advice to me. In my first recollection of him in the early 1960s he was insisting on the significance of Tunisia’s precolonial past, of a specifically Tunisian political community more or less within its present boundaries since the seventeenth century. He was perhaps responding to my dissertation (Moore 1965) or to an earlier work (Micaud et al, 1964) where I analysed the colonial dialectic. Modern Tunisia, he argued, did not commence with a French presence to be emulated (Young Tunisians), then rejected (Old Destour), then overcome by Bourguiba’s Francophile legions. As he would later explain, Bourguiba is better seen as following in the footsteps of Kheireddine (Zghal, 1979: 44-45).

As a determined academic (and as a political outsider coming from Sfax), Zghal distanced himself from the politics of the Destours and took the longer view of a historical sociologist. But some of his observations still reflect a deep understanding of the colonial dialectic. How, for instance, are we to understand his unforgettable observation that Rached Ghannoushi can be seen as Bourguiba’s ‘illegitimate offspring’ (Zghal 1991: 205)? On one level Ghannoushi could be viewed as the product, however resentful, of Tunisia’s modernizers and their underlying culture. As the Egyptian sociologist Saad Eddine Ibrahim observed after interviewing him in 2011, Ghannoushi was not just one but rather two generations ahead of those Muslim Brothers Ibrahim knew so well in Cairo. But there is another interpretation. Tunisia’s Supreme Combatant had produced an ‘army of the defeated’ (Burgat 1992), those Zitouna secondary school students, far more numerous than their French-educated cohorts at independence in 1956, who were excluded from all higher education except theology. Ghannoushi (born in 1941) was indeed a victim of Bourguiba’s assault on Zitouna in the late fifties ‘ an illegitimate offspring or, to pursue the ‘Supreme Combatant’s’ military metaphors, collateral damage in the ‘struggle against backwardness’ (Moore 1970: 104).

Tunisian Islamism was yet another response within a broader dialectic that had engaged both Kheireddine and Bourguiba. Whether before or after the colonial occupation and independence, their country was still in a situation of ‘cultural dependence, both technological and economic and consequently political’ (Zghal 1979: 44) that irreversible processes of globalization further strained. Once the peasants of Ouardanine put an end to Ben Salah’s cooperatives ‘ an outcome that might have been prevented, had some of Zghal’s earlier studies (1968) been taken into account ‘ the regime’s developmentalist legitimacy waned. Zghal was acutely aware by the late seventies of the limitations of internal Destourian and external Marxist oppositions that might have shielded the Arab world’s ‘only surviving civil republic’ from an Islamist counter attack. He dismissed the ‘Tunisois’ effort in 1971 to nurture a process of democratic opposition within the party as fixated on voting procedures, appealing to a limited audience of urban intellectuals despite being a ‘model of moderation and tolerance’ (Zghal 1979: 52). As for ultra-Leftists, they had no roots in Tunisian culture. He argued that the Movement of the Islamic Tendency was a more plausible response to growing numbers of anomic youth in search of identity as well as economic security, but that it was likely to split into many tendencies.

Instead, the Movement survived Bourguiba and, reformed as the Nahda, became Tunisia’s strongest opposition party. The question then arose whether it was part of ‘civil society,’ a concept that rapidly travelled to the Middle East and North Africa after liberating Poland in 1986 and shattering the Berlin Wall the following year. In North America we speculated about civil society in the MENA. Our specialists in the area established a little intellectual ghetto in the American Political Science Association where we exchanged short papers discussing how civil society might be gradually tempering and possibly subverting the authoritarian regimes of the region. At this time Zghal, too, was analysing the historical contexts of civil society formation from Locke and Hegel to Gramsci and Polish Solidarity. In retrospect as I read his contribution to the Annuaire de l’Afrique du Nord of 1989, I see how well it might have fit my reconstructions of the concept’s travels taught at the University of Texas at Austin.

Zghal noted at the time that a representative of the Nahda signed Ben Ali’s National Pact of 1988, when the changement promised by him and his political brain, Hedi Baccouche, still seemed to be on track. He then noted that one of Nahda’s more moderate leaders, Abdelfatah Mourou, reneged on the Pact in 1989 when he called for the resignation of the Education minister for reforming religious textbooks. Yet the National Pact had insisted on such reform. The signers of the Pact, including the Nahda representative, called on the state ‘to sustain this rational orientation resulting from ijtihad and to strive for ijtihad and rationality having a clear impact on education, religious institutions, and the media (1989: 210, underlined by Zghal). In rejecting such reform, Nahda was breaking with the national consensus. Some of its members campaigning in the legislative elections of 1989 were ‘often in flagrant contradiction’ with the National Pact, for instance in attacking the 1956 Code of Personal Status embodying women’s emancipation. For this and similar deviations, had not the Nahda excluded itself from civil society, the only operational definition of which at the time was the National Pact?

Or, conversely, could civil society be understood to represent all the social forces articulated in associations, whatever their views or images of state and society? As Ben Ali engaged after 1990 in systematic repression of the Nahda and then of all forms of opposition to his corrupt regime, civil society was reshaped into constellations of coopted associations, with women forming the regime’s strongest defense, and alliances of Destourian dissidents, human rights activists, and Islamists in opposition. Repressed and driven underground, with many of its leaders including Ghannoushi in exile for two decades, the Nahda allied with weaker secular oppositions and regained a possible status in the civil society reviewed by Zghal and Ouerderni in 2009.

Reading between the lines the concluding comparison between Poland, on the one hand, and Egypt and Tunisia, on the other, the authors may be more prescient than they intended (unless, indeed, writing under Ben Ali’s strict censorship, their apparent despair covered new hopes for change). In their conclusion they singled out the two states in the region hosting the most continuous public administrations, those necessary complements to civil society. These states were not only more comparable to one another than, say, to Syria or Libya. They also offered better frameworks for civil society. The significant difference with Poland was the latter’s Western orientation of a Catholic Church in contrast to ‘the identification of the Arabs with Islam and Arab-Islamic civilization in profound concern over the determination of the West to exercise a neo-imperial form of domination’ (2009: 28). While their conclusion was that globalization was likely to pulverize any religious solidarities into secular individualism, the very fact of comparing Tunisia and Egypt with Poland indeed foretold the Arab Spring.

I caught up with Zghal in 2011 and 2012 after absenting myself from Tunisia during much of the Ben Ali era out of concern for younger more vulnerable Tunisians whose contact with me could have whetted the repressive appetites of Ben Ali’s ‘sweet little’ rogue regime (Henry 2007). Friends told me he had taken a new lease on life after witnessing the end of the police state and an ongoing transition, hopefully to a new democracy. He indeed was his old self, sipping his mint tea at the Safsaf Caf® of La Marsa and later, on my second visit, confronting me with three ‘enigmas.’

Spontaneous (rhythmic) demands for dignity, not associations nor religious leadership, orchestrated the Revolution of January 14,

Religious forces hijacked the revolution, and

Al Aridha Chaabia (The Popular Petition Party), arising out of nowhere, became Tunisia’s third largest party in the Constituent Assembly.

If I understood him correctly, Zghal was looking as usual beyond day-to-day politics, this time to deep social cleavages expressed in the Tunisian revolution. The appeal of Al Aridha exposed the irrelevance of those debates between ‘secularists’ ‘the Francophile la├»cistes’and the ‘Islamists”whether Nahda or Saudi-style Salafists. While proposing that teams of researchers analyze the discourses of the Constituent Assembly so as to discover ways of bridging the ideological divide, Zghal seemed more concerned about the marginalized Tunisians who after all had launched the revolution and were ready to vote even for empty promises flown in or delivered over his private TV stations by a businessman in exile, so vacuous were the other parties on the ground, headed for the most part by the chattering classes in Tunis and the Sahel who seemed out of touch with the revolution.

Sociological analyses of the 2011 elections offer a closer look at those marginal populations ready to vote for Hechmi El Hamdi, the businessman in exile. A native of Sidi Bou Zid, he garnered 45 percent of the vote from the delegations ‘where the first protests broke out in late 2010 (Sidi Bouzid, Sidi Ali Ben Aoun, Menzel Bouzaiene, Regueb, and Souk Jedid), compared to only 16.5 percent for the combined votes of the Nahda and its two secular allies’ (Koehler and Wakotsch, 2015: 27). In the authors’ data set the unit of analysis was not the governorate but the delegation, Tunisia’s 264 lower units of administration offering a more fine grained view of voting behavior. Offered access to the data set, I regressed the vote for the party (6.9 percent nation-wide) on illiteracy, urbanization, and unemployment, three indices of a delegation’s marginality. Controlling for the governorate of Sidi Bou Zid, Al Aridha’s ‘fortress’ (Hababou and Amrouche, 2013), one of the least literate and urban Tunisian governorates, high rates of illiteracy and low levels of urbanization still significantly contributed to the Aridha vote. Unemployment, however, only weakly and negatively correlated with the vote, perhaps because there was relatively little variation in unemployment across the country. The revolution seemed less about jobs than about dignity.

None of Tunisia’s governing parties of the ‘troika’ particularly appealed to those marginal populations living in predominantly rural delegations with relatively high rates of illiteracy. Al-Nahda, the party-movement that had tried in Zghal’s perception to hijack the revolution, not only had little appeal in Sidi Bou Zid. Its vote by delegation was significantly correlated with delegations having greater literacy and urbanization. So also were the votes for its allies, both the Congr├¿s de la R®publique (CPR) and Ettakatol. Remnants of Destour opposition fared no better in marginal delegations. Their votes, too, were significantly correlated with literacy and urbanization. Illiteracy and rusticity tended instead to be associated with voting for other smaller parties, wasted votes, and lower voter turnout. Both the government and opposition to which the elections of 2011 gave rise tended to ignore the marginal elements that lay at the heart of the social revolution in Sidi Bou Zid.

Tunisia was and remains in the midst of two sorts of revolution, a political transition of the sort advocated by Hannah Arendt, On Revolution (1963), for whom the social content of the French or Russian revolutions was anathema, and a postcolonial social revolution of longue dur®e, possibly deepening and democratizing Kheireddine’s enterprise. Divisions between secularists and Islamists not only placed the political transition in serious jeopardy but also distracted attention from the revolutionary social realities underlying it.

Civil society only in a very narrow sense protected the first stage of the political transition. As civil or madani, pertaining to the city and more particularly to the capital, civil society was personified by three Tunisois who navigated it through dire straits to the elections of October 2011. With no time for outside consultations in the crisis of Casbah 2, Transitional President Fouad Mbazaa called on his erstwhile (1960s) patron Beji Caid Sebsi to replace Ben Ali’s beleaguered prime minister. The third Tunisois, Yahd Ben Achour, serendipitously extended his technical constitutional advisory committee into a self-coopting transitional assembly of up to 155 notables representing civil society and giving its imprimatur to laws negotiated with Caid Sebsi for the president to issue as decrees.

Fortunately Tunisia’s new freedom revived institutions of a more deeply rooted civil society. The UGTT in particular helped the bickering parties following the election of the Constituent Assembly to navigate the more difficult passages of transition. Joined by UTICA, the Tunisian Bar Association, and the Tunisian League of Human Rights, the UGTT led a Quartet that pressured the politicians to restrain their respective fits of paranoia, stop their strikes, and complete work on the new constitution. To return to the concept of civil society, it seems by 2015 to have transcended the debate between secularists and Islamists by becoming the necessary arbiter.

Meanwhile in May 2013 Zghal famously signed up as a member of Nidaa Tunis, Beji Caid Sebsi’s party, so as not to ‘die idiot.’ In his open letter he also singled out Rached Ghannoushi as the most efficient or ‘performing’ of political entrepreneurs, probably not a compliment coming from a sociologist although he claimed that some of his best friends were political entrepreneurs, presumably in academia. He indeed lived to see his party beat the Nahda in the legislative elections of 2014 and then to his party leader’s victory over the incumbent, Moncef Marzouki, in the presidential elections at the end of the year. But he was surely also aware, especially given his background in historical sociology, that any political successes at best masked those social realities that underlie the Tunisian revolution.

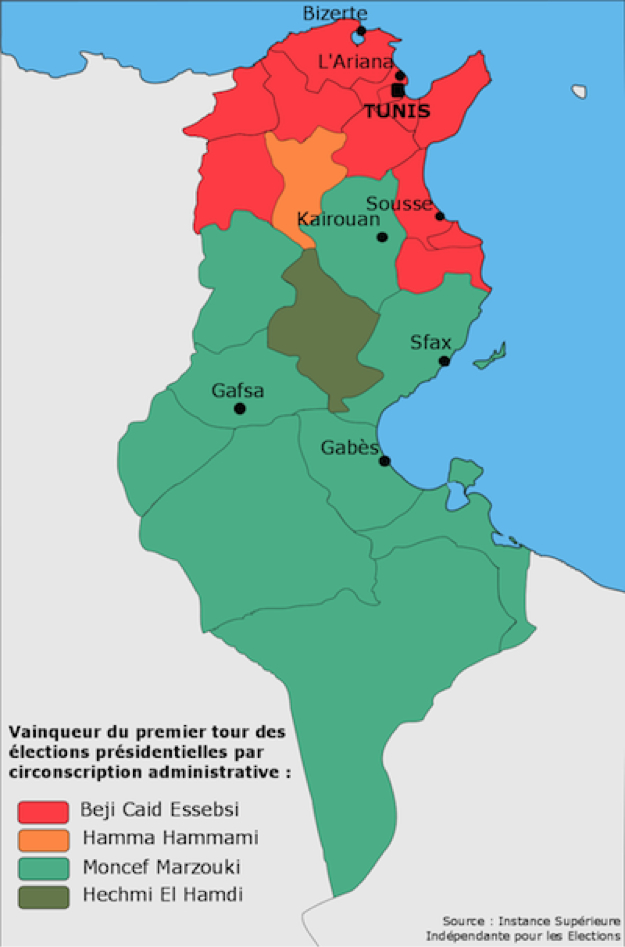

Tunisia seemed dangerously divided between the northern governorates, all offering Beji Caid Sebsi comfortable majorities in the presidential elections, and the southern ones carried by Marzouki, sometimes as in Gabes, Mednine, and Tataouine by lopsided majorities (of respectively 80, 81, and 86 percent). In the

Source: Nicholas Hautemanière (2015) http://www.lesclesdumoyenorient.com/Une-transition-democratique.html

parliamentary elections of both 2011 and 2014 these three of the nine governorates voting for Marzouki (see map) had also produced the strongest majorities for Al-Nahda. In the second round of the elections Caid Sebsi added El Hamdi’s Sidi Bou Zid and Hammami’s Siliana to his portfolio of governorates, but the entire South and much of central Tunisia stayed with Marzouki and became the big losers. On average, the region was less literate and urban than that of the winners. Sewage facilities were especially deficient (with a mean of only 23 percent in Marzouki territory, compared to 54 percent elsewhere, statistically significant differences even controlling for urbanization), reflecting not a dryer climate but rather years of public neglect. Within the marginalized region Al-Nahda’s base also recalls earlier divisions between Bourguibists and Youssefists and subsequent tendencies in the South to listen more to Qadhafi’s Tripoli than to Tunis. Libya of course became far more potentially destabilizing after the killing of the dictator.

Consequently Al-Nahda’s participation in the government is a wise precaution. The young Tunisian democracy is too fragile to organize experiments in constructive opposition characteristic of a consolidated democracy. Moreover the cultural issues raised by any Islamist opposition would hardly alleviate the social pressures that remain intense in this ongoing social revolution. Arguably, however, the pieces are now in place for a democratic deepening of the social revolution launched from above by Kheireddine and Bourguiba. The principal instrument of the deepening is neither Nidaa Tunis nor Al-Nahda but rather Tunisian civil society’s Quartet.

The UGTT in particular has played an astounding series of roles in the Tunisia’s revolution. First, in 2008 its local militants organized six months of protests against the Sfax Gafsa Company for widespread nepotism and corruption in recruiting and managing the miners of Metlaoui and Redayef. In Tunis Ben Ali had reduced the central union leadership to preserving its shred of autonomy by refusing to take up its allotted seats in prefabricated parliament (so as not to have the required elections hijacked by RCD partisans ‘ Henry 2011 n. 21). It was obliged to discipline or expel much of its regional leadership until, after Ben Ali’s departure, it rescinded these measures and subsequently renewed the top leadership in Tunis.

Meanwhile, the cries from Sidi Bou Zid would never have gained political traction without a syndicate on the spot to publicize and even misrepresent the humiliation of Mohammed Bouazizi, who was originally framed as an unemployed graduate. A number of other Tunisians had immolated themselves or drowned since 1990 without triggering a revolution. While the UGTT leadership in Tunis remained loyal to the regime until the day Ben Ali departed, its cadres in peripheral governorates gave support and sustenance to the revolution as it progressed from Thala and Kasserine to Sfax and up the coast. The UGTT also reinvigorated the revolution with Casbah II, leading to the consolidation of the transitional Tunisois regime.

The subsequent ability of the union to work with the other members of the Quartet and discipline dogmatic secularists and Islamists is well known. The successful resolutions of a series of crises in turn offer a foundation for further progress. The UGTT will undoubtedly continue to play a critical role because its million members bridge the capital city to Tunisia’s many peripheries. Within the union Islamists and secularists have learned to coexist. It is now called upon to negotiate social compromises with the business community yet also to sustain its regional bases. It must at the same time be ready to defend social progress in the face of cultural grievances, perhaps using them up to a point in negotiations with the government and UTICA.

Unlike the Destour rooted in Tunis and the Sahel, the UGTT has strong southern roots to keep the Nahda in check. In his parting words Zghal (2013) explained, ‘the challenge is no longer between local Salafists and local modernists, with the central role played by the trade union organization in managing the consensus. The challenge is the decision taken by the political direction of the Nahda Party to never engage in public debate between Islamists and non-Islamists over definitions between the religious and the political. We have observed that the direction of the Nahda Party has taken the habit of retreating whenever pressure was strong. In short, Zghal gives us hope that the UGTT may sustain its incredible balancing act.

Many still question whether the Arab ‘spring’ really was a revolution. Only states such as Egypt and Tunisia with real histories and the continuity of a capital city could acquire a durable civil society, much less remove a tyrant without outside help or interference. Political transition has failed for the time being in Egypt while indirectly contributing to Tunisia’s success. But both societies still face considerable unrest, as the youth will not forget 2011.

Zghal used to take pride in Tunisia being the last Arab republic to remain civil. To survive as such in its new permutation it must attend to the marginal populations that sparked the revolution. May Tunisia live up to his memory.

This publication will be part of Mohamed Kerrou’s:

Le sociologue et le politique. Hommage – Abdelkader Zghal (1931-2015).

Textes r®unis et pr®sent®s par Mohamed Kerrou,

Tunis, C®r├¿s Editions, 201

Clement Henry, who wrote until 1995 under the name of Clement Henry Moore, has conducted research on political parties, the engineering profession, and financial institutions in various parts of the Middle East and North Africa since 1960. Before coming to Singapore in November 2014 he was chair of the Department of Political Science at the American University in Cairo, after having retired from the University of Texas at Austin in 2011. Earlier he had directed the Business School at the American University of Beirut, taught at the University of California, both at Berkeley and Los Angeles, at the University of Michigan, and at the Institut d’Etudes Politiques in Paris. He is currently studying Islamic finance, following up on his Politics of Islamic Finance (2004), co-edited with Rodney Wilson, and is also working with Robert Springborg on a third edition of their Globalization and the politics of development in the Middle East (2001, 2010). He has also tried to trace the career patterns and politics of a cross section of Algeria’s retired political elite, drawn from interviews with student leaders whom he interviewed in 1955-1962: T®moignages (2010, 2012). Recently he co-edited The Arab Spring: Will It Lead to Democratic Transitions? (2013). Clement Henry received his PhD in political science from Harvard University and an MBA from the University of Michigan.

References

Fran├ºois Burgat, ┬½ Rachid Ghannuchi : Islam, nationalisme et islamisme (entretien) ┬╗, ├ëgypte/Monde arabe, Premi├¿re s®rie, 10 | 1992, mis en ligne le 07 juillet 2008, consult® le 28 avril 2015. URL : http://ema.revues.org/1420

Nicholas Hautemani├¿re, Une transition d®mocratique nouvelle, des tensions anciennes : retour sur les ®lections l®gislatives et pr®sidentielles tunisiennes, Les cl®fs du Moyen Orient, January 1, 2015: http://www.lesclesdumoyenorient.com/Une-transition-democratique.html

Clement M. Henry, Tunisia’s ‘Sweet Little’ Regime, in Robert Rotberg, ed., Worst of the Worst: Dealing with Repressive and Rogue Nations, Brookings Institution Press, 2007, pp. 300-323. http://www.la.utexas.edu/users/chenry/public_html/12-7567-6%20CH%2012.pdf

Clement M. Henry, Tunisia at the Crossroads, 2011 https://freedomhouse.org/report/countries-crossroads/2011/tunisia#.VUc6UZO2W3g

Kevin Koehler & Jana Warkotsch, Tunisia between Democratization and Institutionalizing Uncertainty, in Khalil al-Anani and Mahmoud Hamad (eds.): Elections and Democratization in the Middle East, (Basingstroke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), pp. 9-34.

Charles A. Micaud, with L. Carl Brown and Clement H. Moore, Tunisia: the Politics of Modernization, New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1964.

Clement Henry Moore, Tunisia since Independence: The Dynamics of One-Party Government, Berkeley and Los Angeles: The University of California Press, 1965

Clement Henry Moore, Politics in North Africa, Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1970.

Abdelkader Zghal, ‘L’®lite administrative et la paysannerie en Tunisie,’ Annuaire de l’Afrique du Nord, VII (1968), 129-137.

Abdelkader Zghal, ‘Le retour du sacr® et la nouvelle demande id®ologique des jeunes scolaris®s: le case de la Tunisia,’ Annuaire de l’Afrique du Nord, XVIII (1979), 41-64.

Abdelkader Zghal, ‘Le concept de soci®t® civile et la transition vers le multipartisme,’ Annuaire de l’Afrique du Nord, XXVIII (1989), 207-228.

Abdelkader Zghal, The New Strategy of the Movement of the Islamic Way: Manipulation or Expression of Political Culture? in I. W. Zartman, ed., Tunisia: The Political Economy of Reform (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1991), 205-217.

Abdelkader Zghal and Ahmed lahd Ouederni, Introduction: les enjeux politiques et ®pist®mologiques de la reactivation et de la circulation transnationale et transculturelle du concept de soci®t® civile, Arab World Report, 2009 Conference, International Sociological Asociation, 13-29: http://www.isa-sociology.org/colmemb/national-associations/en/meetings/reports/Arab%20world/Introduction.pdf (retrieved April 29, 2015).

Abdelkader Zghal, A 83 ans, Abdelkader Zghal adhère à Nidaa Tounès «pour ne pas mourir idiot» http://www.leaders.com.tn/article/11512-a-83-ans-abdelkader-zghal-adhere-a-nidaa-tounes-pour-ne-pas-mourir-idiot (30 May 2013)