By Retna Devi

Tenets of Humanitarianism

Humanitarianism often elicits a cynical response as it is usually perceived as having strayed from the original values of impartiality and neutrality’concepts that Henri Dunant, an important humanitarian figure, utilised in his book A Memory of Solferino to introduce the idea of humanitarian assistance to the European public. However, this is simply pegging humanitarian action to an unrealistic standard that it has not been able to achieve. Neutrality and impartiality are ideals that are ‘patchy, weak or simply non-existent’ because instrumentalisation, usually in the form of manipulation and politicisation, is an inherent quality of humanitarian assistance resulting from the competition for space and funding, among other reasons.[1] One such manifestation of instrumentalisation is ”forgotten’ emergencies, crises where politics trumps humanitarian action’where consolidated UN appeals fall on deaf ears”[2]

Libya serves as a good example of a crisis that has fallen through the cracks. “[The West] abandoned [Libya] to its fate,” or “President Obama has washed his hands of Libya,” are common refrains used to describe the situation after the military intervention in 2011.[3] Could this be primarily due to the inability to reconcile Libya with the national interests of donor countries? Through examining the surge and decline of interest in Libya and how this affects humanitarian action, we can better understand the political economy of humanitarian assistance.

The types of aid that will be examined are both humanitarian and development aid.[4] Although these two types of aid aspire to achieve different things, concerns related to providing immediate relief and reconstruction operations began to overlap in the 1990s.[5] This led to the birth of what is now known as new humanitarianism, which has further politicised aid.[6] The data is taken from the United Nations’ Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). While official funding, especially for development aid, may not provide a detailed picture of the flow of funds, it is sufficient in trying to understand the funding patterns of donor states. The countries selected-the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and Italy -are those that participated in the intervention that led to the toppling of Libya’s autocratic ruler Muammar Gaddafi.

Libyan Context

The conflict and the civil war that ensued in Libya were precipitated by the Arab Uprisings in 2011. Anti-Gaddafi protests that began to pick up steam in February 2011 were met with disproportionate violence by Gaddafi’s security forces. With the passing of the United Nations (UN) resolution on the ‘right to protect,’ the United States embarked on Operation Odyssey Dawn which was then replaced by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)-led Operation United Protector. These military interventions turned the tide against Gaddafi’s forces and on 20 October 2011, Gaddafi was captured and killed by rebel fighters. With the demise of the Libyan dictator, NATO ended its military campaign at the end of October 2011.[7] Unfortunately this was not the end of Libya’s problems. Differing vested interests among the rebel groups prolonged the fighting and led to two governments being established in Tripoli and Tobruk, respectively.[8] This political instability and fighting among the various factions effectively destabilized the lives of thousands of people.

As of July 2015, 434,000 people including families have been recorded as being internally displaced.[9] Since the beginning of the conflict, 660,000 people from Libya have sought shelter in Tunisia and Egypt.[10] Although the situation improved slightly in 2012, 50,000 people were still unable to return to their homes. In 2014, there was a new wave of fighting and 400,000 people were uprooted. According to the UN Humanitarian Coordinator for Libya, approximately 1.3 million Libyans are currently food insecure.[11] He also noted that there is a ‘deterioration of health, sanitation and educational services and drinking water supply shortages.'[12] In addition, Libya is often a stopover for refugees heading to Europe. It is estimated that there are 250,000 refugees, asylum-seekers and migrants in Libya, adding to an already tenuous situation in the country.[13] This paints a rather bleak picture for Libya and is indicative that it is in need of any assistance possible. Yet aid continues to trickle in, barely sustaining the affected population. Only 37 percent of the Humanitarian Response Plan by UN for 2014-2015 was funded. Although it is still in the relatively early stages for the 2015-2016 appeal, donors’ response do not seem too promising with only 2.7 percent of the required funding being met. These are common indicators of aid being instrumentalised because it suggests that there are other factors, apart from the traditional humanitarian principles, influencing the flow of aid

When we try to understand why humanitarian aid has been less than adequate, a few reasons surface. Libya is an oil-rich country and it is believed to have resources that will be able to mitigate the suffering of people.[14] However, the country’s oil production has been in decline since the conflict started, and as pointed out in the discussion, ‘An Overlooked Crisis: Humanitarian Consequences of the Conflict in Libya,’ organized by the Brookings Institute, ‘long term reliance of displaced persons’ resources is not tenable.'[15] Another reason that comes to mind is that donor countries might be focussing on other emergencies, such as Iraq and Syria. This then raises the question of how donor countries decide which country to channel monetary contributions to. The most likely answer is that their contributions are usually in line with the donor nation’s strategic interests. This manipulation and politicisation of aid has become the norm since the 1990s when ‘states were helping to bulk up the humanitarian sector’mainly because they believed that humanitarian action would advance their foreign policy interests.'[16] This sentiment cannot be divorced from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) either as they often receive large amounts of funding from governments and UN agencies, making them ‘force multipliers’ for governments. [17]

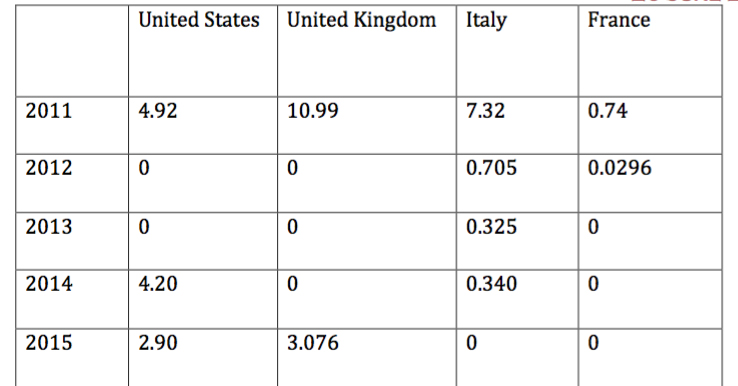

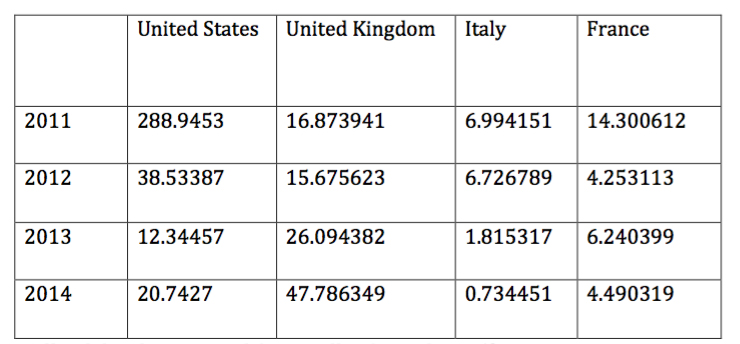

To verify if this holds true for the case of Libya, the funding patterns of the United States, France, United Kingdom and Italy will be briefly examined. From a quick glance at the figures below, it is apparent that there has been a drastic decline of assistance over the years. 2011 saw the most contributions by these countries as they were all involved in the military intervention at one point or another. In the next section, we will look at the individual nations, which have different relations with Libya, to ascertain if their contributions are a reflection of their vested interests in Libya.

Table 1: Humanitarian funding (USD million) per donor based on financial tracking service by OCHA.[18]

Table 2: Official development aid (USD million) per donor.[19]

United States

Prior to the fall of Gaddafi, the United States had a rather fragile relationship with Libya. Although the administration viewed Gaddafi as “temperamental and [someone who] makes decisions based on personal relationships,” he was regarded as an important partner in the US’ counterterrorism efforts and was necessary in the US’ expansion of influence in Africa through the United States Africa Command (AFRICOM), which it wanted Libya to be part of.[20] Gaddafi and the Libyan populace, however, “remained wary of initiatives that put foreign military or intelligence assets too close to their borders,” therefore stalling America’s plans in the continent.[21] Energy-wise, there were some US oil companies with interests in Libya, but it is Europe that continues to be more reliant on Libya’s petroleum and natural gas.[22]

Keeping the above in mind, the US military intervention was in accordance with the country’s pragmatic approach as it was meant to benefit American strategic interests. They would be seen as supportive of the Arab people, not the dictators. It also meant that AFRICOM would not be impeded as they were willing to remove Gaddafi by destroying his military capabilities or enabling the rebels to gain control of Tripoli.[23] Unfortunately, the intervention did not bring about the desired result as various political, tribal and regional factions began to engage in a power struggle, and the US did not find itself with a pliable state.[24] Moreover, the US also had to deal with issues such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the Syrian crisis while attempting to pay attention to other regions.[25] This led to the decision of disengaging from Libya, more so after the bombing of the American diplomatic compound in Benghazi in 2012. The US’ drop in funding reflects the state’s willingness to instrumentalise aid as Libya was no longer strategically relevant to the donor, with only a marginal increase in 2014 due to the intensification of the conflict.

France

As for France, it took the lead in pushing for the NATO intervention. President Nicolas Sarkozy saw this as an opportunity to leverage France against Germany which had been at the forefront of European affairs since the European debt crisis in 2009.[26] It was also an opportunity to assess France’s “reintegration into the NATO command structure.”[27] Another factor that may provide a better understanding of France’s eagerness in acting swiftly against Gaddafi is that the French presidential elections were around the corner and Sarkozy was not viewed favourably by the public.[28] True to the nature of humanitarian instrumentality, he contributed more humanitarian aid and development aid in 2011, and used his involvement in Libya to boost his approval ratings.[29]

Despite such interests in Libya, France’s monetary contributions were ┬áon the low side. However it declined even further, especially for humanitarian aid, from 2012 onwards. This was during the time when the new president, Fran├ºois Hollande, entered office. Unlike Sarkozy, Hollande adopted a less aggressive stance with Libya. In fact, he was willing to wait on the sidelines in 2013 as there had been no formal request by the Libyan government to intervene and he believed that it was the United Nation’s responsibility to take any action.[30] Hollande was also preoccupied with other issues such as the Ukraine crisis and civil war in Syria, which may explain the diversion of resources from Libya, which was no longer regarded as important for France.[31]

United Kingdom

The funding patterns for the United Kingdom differ slightly from the other donor countries. Although the data does not indicate any humanitarian assistance from 2012-2014, there were significant contributions in development aid in those years, especially 2013 and 2014. This can possibly be explained by its economic interests. As for politics, the UK did not have much of a reason to be involved in the intervention apart from maintaining relevance in the region and Washington.[32] After the attack on the US consulate, Libya which was previously considered a success story by the UK began to disappear from the country’s political discourse.[33] However, it has considerable energy interests as British oil and gas giant BP announced its intention in 2009 to invest US$20 billion in Libya for 20 years.[34] Hence, it was in the UK’s best interest to focus more on the development aspects of Libya rather than humanitarian aid’a clear manipulation of funds. Whether this will continue remains to be seen as the conflict has impeded BP’s oil exploration programmes in Libya causing it to write off oil assets worth millions of dollars.[35]

Italy

If we are to follow the rationale that aid is determined largely by national interests’ of the donor country, then Italy, the former colonial ruler, may seem like an anomaly. It is geographically close and its energy company Eni has been functioning in Libya since 1958 and is still operational despite the conflict.[36] These are just some of the ways Italy has benefitted from a close relationship with Gaddafi and Libya at large. In spite of this, the monetary contributions by Italy have been insufficient. There are a few reasons for this. Italy is not a prominent donor to begin with and its economy had been shrinking. By 2013 it had the largest public debt in the Eurozone, therefore necessitating a reduction in funds.[37] . Although it could not provide monetary aid, it found other ways to assist Libya, such as hosting talks with the two rival Libyan governments in order to find a political solution that will bring an end to the fighting. This is of importance to Italy as it is affected by events in Libya due to close proximity as seen by refugees heading to Italy. Italy’s behaviour as a donor country fits the narrative of the instrumentalisation of humanitarian assistance. The interests of its own country come first and the support it provided will ultimately benefit Italy as well. Therefore, it is once again proven that neutrality and impartiality are not driving forces of aid.

Conclusion

From the case of Libya, It is apparent that a decrease in strategic importance to donor countries, domestic issues and other emerging conflicts are reasons enough for instrumentalising humanitarian aid. For states, aid has come to be a tool used for manipulation. Abiding by the principles of neutrality and impartiality is not beneficial in any way to these countries; hence the politicisation of humanitarian assistance will continue to persist. It is for this reason that Libya will most likely not remain underfunded or ‘forgotten.’ With Daesh gaining control of certain parts of the country, Libya is beginning to receive attention from Western governments because now it involves the ‘war on terror,’ which is highly relevant to them.

Retna Devi is a Senior Executive at MEI and holds a BA in History from the National University of Singapore. Her research interests include gender relations, development and humanitarian aid as well as the cultural history of the Middle East.

[1] Ian Smillie, ‘The Emperor’s Old Clothes: The Self-Created Siege of Humanitarian Action,’ in The Golden Fleece: Manipulation and Independence in Humanitarian Action,’ ed. Antonio Donini (Virginia:Kumarian Press, 2012).

[2] ibid.

[3] Richard Spencer, ‘How the West rode in to save Libya, then abandoned it to its fate,’ The Telegraph, July 20, 2014, accessed May 20, 2016, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/libya/10995886/How-the-West-rode-in-to-save-Libya-then-abandoned-it-to-its-fate.html; ‘That it should come to this,’ The Economist, January 10, 2015, accessed May 30, 2016, http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21638123-four-year-descent-arab-spring-factional-chaos-it-should-come.

[4] Humanitarian aid is usually a short-term response to human suffering in complex emergencies or natural disasters; however the duration of aid offered depends on the extent of the emergency. On the other hand, development aid or assistance is a long term endeavor of equipping states with sustainable financial and/or technical support so that they will be able to handle or prevent future crises.

[5] Michael Barnett, Empire of Humanity: A History of Humanitarianism (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011).

[6] Daniela Nascimento,’One step forward, two steps back? Humanitarian Challenges and Dilemmas in Crisis Settings,’ The Journal of Humanitarian Assistance, accessed March 23, 2016, https://sites.tufts.edu/jha/archives/2126.

[7] Madelene Lindstrm & Kristina Zetterlund, ‘Setting the Stage for the Military Intervention in Libya: Decisions Made and Their Implications for the EU and NATO,’ FOI-Swedish Defense Research Agency (2012).

[8] Rebecca Murray, ‘Libya: A tale of two governments,’ Al Jazeera, April 4, 2015, accessed March 23, 2016, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/04/libya-tale-governments-150404075631141.html

[9] ‘Libya,’ Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, accessed March 23, 2016, http://www.internal-displacement.org/middle-east-and-north-africa/libya/.

[10] ‘An overlooked crisis: Humanitarian consequences of the conflict in Libya,’ Brookings, accessed March 23, 2016, http://www.brookings.edu/events/2015/04/24-libya-displacement-overlooked-crisis.

[11] Emma Rumney, ‘Humanitarian aid plea for Libya goes virtually unanswered,’ Public Finance International, accessed March 23, 2016, http://www.publicfinanceinternational.org/news/2016/02/humanitarian-aid-plea-libya-goes-virtually-unanswered; Going by the definition provided by World Health Organization, food insecurity refers to people not having access to sufficient amounts of nutritious food on a regular basis. Could you maybe explain what that means?

[12] ‘UN warns of severe humanitarian aid shortage in Libya: world community provided only 2.6 percent of required aid,’ UN Information Centre in Cairo, accessed March 23, 2016, http://www.unic-eg.org/eng/25019.

[13] Libyan Humanitarian Country Team, ‘ 2015 Libya: Humanitarian Needs Overview,’ accessed March 23, 2016, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/system/files/documents/files/libya_hno_summary_final_english_0.pdf

[14] ”Libya can’t fend for itself’: UN official says 1mn in dire need of urgent medical supplies,’ RT, February 24, 2016, https://www.rt.com/news/333443-libya-aid-un-crisis/.

[15] ‘An overlooked crisis’; Armin Rosen, ‘Libya’s Oil Sector is in Freefall as the Country Collapses,’ Business Insider, August 7, 2014, http://www.businessinsider.sg/libyas-oil-sector-is-in-freefall-2014-8/?r=US&IR=T#.VuprcPl96Uk.

[16] Barnett, Empire of Humanity.

[17] Elizabeth G. Ferris , The Politics of Protection: The Limits of Humanitarian Action (Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2011);Donini, The Golden Fleece.

[18] ‘Libya,’ Financial Tracking Service, accessed March 23, 2016, http://ftsbeta.unocha.org/countries/121/summary/2016.

[19] ‘Aid (ODA) disbursements to countries and regions,’ OECD, accessed march 23, 2016, http://stats.oecd.org/qwids/#?x=1&y=6&f=2:98,4:1,7:1,9:85,3:51,5:3,8:85&q=2:98+4:1+7:1+9:85+3:51+5:3+8:85+1:9,13,23,24+6:2011,2012,2013,2014&lock=CRS1.

[20] ‘The visit of General William Ward to Libya, March 10-11,’ WikiLeaks, accessed March 23, 2016, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/09TRIPOLI202_a.html; Youssed M. Sawani, ‘The United States and Libya: turbulent history and uncertain Future,’ E-International Relations, December 27, 2014, accessed March 23, 2016, http://www.e-ir.info/2014/12/27/the-united-states-and-libya-turbulent-history-and-uncertain-future/;AFRICOM officially came into being during President Bush’s administration as ‘the Pentagon and many military analysts argued that the continent’s growing strategic importance necessitated a dedicated regional command.’ Headed by the US, this military command partners with nations in Africa to carry out joint activities to ensure peace and stability, and protect interests of the US and the region. See Stephanie Hanson, ‘U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM),’ Council on Foreign Relations, accessed June 15, 2016, http://www.cfr.org/africa-sub-saharan/us-africa-command-africom/p13255, ‘Homepage,’ United States Africa Command, accessed June 23, 2016, http://www.africom.mil/.

[21] ‘The visit of General William Ward to Libya, March 10-11,’ WikiLeaks.

[22] Sawani, ‘The United States and Libya.’

[23]’Hilary Clinton Email Archive,’ WikiLeaks, accessed March 23, 2016, https://wikileaks.org/clinton-emails/emailid/5642.

[24] Sawani, ‘The United States and Libya.’

[25] In 2011, Washington issued a series of statements stating Obama Administration’s interest in committing to the Asia-Pacific region. See Danny Russel, ‘Resourcing the Rebalance toward the Asia-Pacific Region, The White House, accessed June 15, 2016, https://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2013/04/12/resourcing-rebalance-toward-asia-pacific-region.

[26] ‘Special Series: Europe’s Libya Intervention,’ Stratfor Global Intelligence (2011), accessed March 23, 2016, https://wikileaks.org/gifiles/attach/128/128797_LIBYA_INTERVENTION.pdf.

[27] Lindstrm & Zetterlund, ‘Setting the Stage for the Military Intervention in Libya.’

[28] ibid.

[29] ibid.

[30] ‘Twenty-second Ambassadors’ Conference ÔÇô Opening speech by M. Fran├ºois Hollande, President of the Republic (excerpts),’ Newsroom-France in the United Kingdom, accessed March 23, 2016, http://www.ambafrance-uk.org/Francois-Hollande-reviews-French

[31] ‘Hollande outlines France’s Africa, Middle East policy,’ France 24, May 31, 2013, accessed March 23, 2016, http://www.france24.com/en/20130531-francois-hollande-interview-france24-africa-middle-east-policies-france

[32] Lindstrm & Zetterlund, ‘Setting the Stage for the Military Intervention in Libya.’

[33] John Warren, ‘Walking Away: The Formation of British Foreign Policy,’ Bellacaledonia, February 24, 2015, accessed March 23, 2016, http://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2015/02/24/walking-away-the-formation-of-british-foreign-policy/.

[34] ‘Special Series: Europe’s Libya Intervention.’

[35] Javier Blas, ‘BP Joins Total in Writing off Oil Assets amid Libya Conflict,’ Bloomberg Business, July 28, 2015, accessed March 23, 2016, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-07-28/bp-joins-total-in-writing-off-oil-assets-amid-fighting-in-libya.

[36] ‘Special Series: Europe’s Libya Intervention.’

[37] Robert Orsi, ‘The Quiet Collapse of the Italian Economy,’ Euro Crisis in the Press, April 23, 2013, accessed March 23, 2016, http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/eurocrisispress/2013/04/23/the-quiet-collapse-of-the-italian-economy/.