A Legal and Geopolitical Perspective on Sukuk in the GCC

By Walid Hegazy

It is no secret that oil production is the primary source of liquidity for petroleum rich Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states. GCC states have employed their capital in the expansion of their own infrastructure, and through different forms of investment in the wider MENA region. With the steady decline in oil prices, GCC states will have to decide whether they can continue to expend their resources at the same rate. GCC countries must find new sources of secure much-needed financing to maintain their economic development and growth plans. Sukuk, which are Shariah-compliant financial instruments sharing characteristics of bonds and investment certificates, may represent a viable option for the government and the private sector in the GCC region. This paper offers a theoretical explanation of sukuk and its legal requirements followed by an analysis of the potential role that sukuk can play in the context of current political and economic shifts in the region.

What are Sukuk?

Sukuk (singular: sak), are certificates of equal value issued in exchange for tangible or intangible assets that grant their holder an ownership stake in a particular asset or contractual arrangement involving the asset.[1] This ownership stake entitles the sukuk-holder to the profits and exposes him to the risks inherent to the performance of such sukuk assets. In this respect, sukuk are similar to investment certificates.

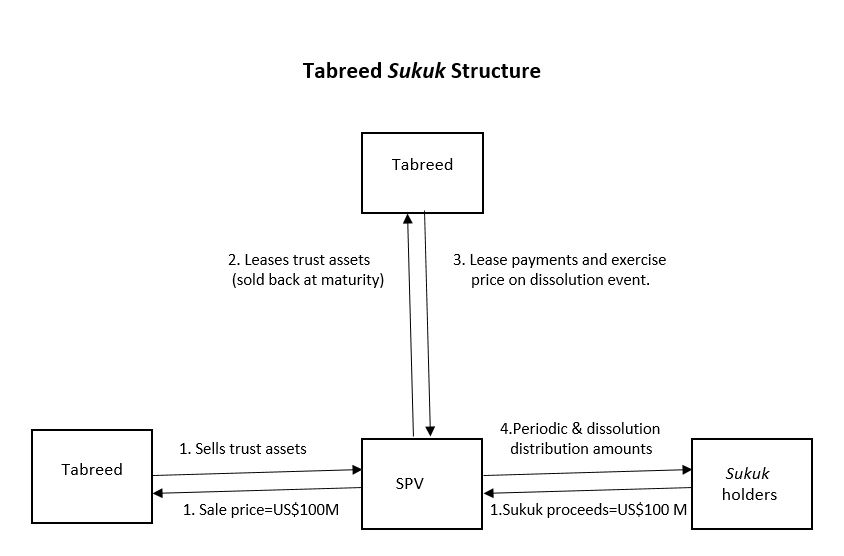

Typical Sukuk Transaction

The first step in the sukuk process is the creation of a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV). SPVs are created to hold sukuk assets and to facilitate the transactions between the issuer, the investors, and any relevant third parties. The SPV is a separate legal entity independent of both the originator and the investors. The SPV is responsible for issuing the sukuk, while also serving as the trustee over the funds received. The legal implications of such arrangements represent a mutual benefit to the originator and the investors. On one side, a change in the originator’s structure (i.e. merger, acquisition, or dissolution) does not affect the contractual relationship of the SPV to the investors (sukuk holders), or their mutual rights or obligations. On the other side, the SPV, rather than the originator, is liable to the investors for delay or default, minimizing the risk to the originator.

The issuer receives the proceeds of the sukuk issuance for the purpose of investing such proceeds in accordance with the agreed terms of the transaction. On the other hand, the investors receive the return on such investments through periodic distribution amounts over the course of the sukuk’s tenure. Periodic distribution amounts are not the same as interest payments, because the underlying concept is that the investor is entitled to the periodic profits that result from the asset or transaction, and there is a contractual understanding that the periodic distribution amounts are proportional to the ownership stake, and fully dependent on the asset’s performance or the success of the transaction. Therefore, the receipt of the periodic distribution amount is not guaranteed, at least in theory. In practice, some sukuk provide terms that guarantee a minimum level of return in addition to recovery of capital.

“Islamic Bonds?” Differentiating Between Bonds and Sukuk

Both sukuk and bonds can be traded in secondary markets, allowing the owner to exchange them for readily useable liquidity, if necessary. Conventional bonds do not meet the standards of Shariah-compliance mainly due to the Islamic principle of riba. Riba is often translated as “usury”, and its prohibition under Islam is sourced from the Quran, which states “And Allah has permitted trade and forbidden usury.”[2] This verse may be interpreted narrowly or broadly. In its most narrow interpretation, Muslims are prohibited from charging any additional amount or benefit over and above the principal amount of a loan. Conventional bonds represent a debt obligation as the bondholder receives an interest rate above principal paid in. While the investor in a sukuk transaction becomes a joint owner of an asset along with his fellow investors, receiving the period distribution amount as a form of ownership profits; a bondholder is simply lending money to the issuer, and profiting from the interest that he is charging the issuer on that loan.

Like bonds, sukuk have a tenure, which is the length of time during which the investor will possess the ownership stake in the underlying asset, as well as the time period over which the underlying transaction will occur. The investor is paid a dissolution payment at the end of the sukuk’s tenure, which represents the value of his ownership stake at the end of the arrangement. While the investor expects that the ownership stake will increase in value over time, he enters into the transaction with the understanding that it may not increase, and in fact, might depreciate. Sukuk comply with the principle of kharaj bi daman, return follows risk. In contrast, purchasers of bond certificates are not exposed to any risk related to the assets or investments underlying the bond issuance while profiting from debt. Also, whereas the price of sukuk is usually determined according to the quality of the underlying asset or initial transaction, the price of bonds is usually determined according to the issuer’s credit rating. It must be noted, however, that despite being controversial from a Shariah perspective, most sukuk issued to date include an undertaking that the issuer is obligated to buy back the sukuk assets from investors at the maturity date at the original purchase price paid by the investors for the same assets at the inception of the transaction.

Classification of Sukuk: Asset Backed versus Asset Based

The crucial elements in differentiating between asset-backed and asset-based sukuk are the type of ownership stake represented by the sukuk, the extent of Shariah-compliance, and the sources of periodic distribution payments. Asset-backed sukuk are issued by SPVs, and the investor is granted full legal ownership in this asset in exchange for his purchase of the sukuk, in proportion with his share. The SPV is able to sell the ownership stakes as the originator has sold it the tangible assets prior to the commencement of the sukuk issuance. The implications of legal ownership are that the investor, in theory, has the right to benefit from the asset and dispose of the asset, a right restricted only by his contractual role and obligations as an investor. The role of the SPV in issuing the sukuk prevents the investors from holding the originator liable for any losses incurred. Should these losses take place, the losses are derived from the poor performance of the underlying asset, because the underlying asset is the source of revenue, profit, and loss. Therefore, asset-backed sukuk are a form of equity, with the ownership shares of existing, tangible assets securitized and sold for a profit. Asset-backed sukuk are in full compliance with Shariah because the transaction is based on a source of legitimate revenue that exists, and the investor is profiting from the asset itself, not from debt or lending, which would be riba.

Asset-based sukuk do not fit the requirements for Shariah-compliance despite the rationale for the creation of asset-based sukuk being investors’ discomfort with the level of risk inherent in asset-backed sukuk. They wanted a debt-like instrument with guaranteed principal and returns above the principal. Asset-based sukuk are quite similar to conventional bonds, in that the source of revenue is the capital of the originator. The originator, in the case of asset-based sukuk, does not form an SPV, but issues the sukuk directly to the investors. The investors do not have legal ownership of any revenue-providing asset, but rather a form of beneficial ownership of assets legally owned by the originator. The originator contracts with the investors to purchase certain assets that he will utilize to gain profit. The price of the sukuk is paid directly to the company, and the company then owes this money to the investors, in addition to any profit. While the issuers of asset-based sukuk do not go so far as to label the periodic distribution amounts as interest payments, in practice, the difference is nominal. In sum, those who invest in asset-based sukuk are trading and profiting in the debt of the originator.

Asset-based sukuk also violate the kharaj bi daman principle, in that the investors, should the originator fail to pay the periodic distribution amounts, can actually seek legal recourse against the originator. The investors not only expect to receive their payments, participating in a reward-bearing transaction at no risk to themselves, but they may, if they so choose, force the originator to fulfill their rights, even in the face of severe losses. It had even become customary for sukuk issuers and investors to conclude a repurchase undertaking agreement. A repurchase undertaking agreement expressly obligates the originator to repay the full purchase value of the sukuk to the investors, whether at the end of the sukuk’s tenure or in the case of default. The practice became so common, that Sheikh Muhammad Taqi Usmani, the chairman of the Bahrain-based International Shariah Standard Council at the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI), declared in 2007 that 85 percent of sukuk were not Islamic.[3] As such, the use of the term “sukuk” in the remainder of this paper, will refer to the Shariah-compliant sukuk, which are asset-backed sukuk.

Common Sukuk Structures

Wakalah Sukuk

Sukuk are also classified according to the underlying Islamic transaction involving the assets. As such, there are various types of sukuk structures. The three sukuk structures with the highest issuance value in 2015 were wakalah, murabahah, and ijarah.[4] The value of most sukuk issuances dropped over the last three years presumably due to lower oil prices. Yet, unlike murabahah and ijarah sukuk, the value of which decreased between 2014 and 2015, wakalah sukuk have been steadily increasing in issuance value since 2013.[5] The underlying transaction is a simple agency agreement, which allows investors to access a larger variety of diverse assets not available to them under murabahah or ijarah sukuk which enjoyed an initial burst of popularity in 2008. These factors have increased their popularity among investors and issuers. First, the SPV issues the sukuk to the investors. Investors gain legal ownership of the underlying assets in the wakalah transaction with the accompanying benefits of the periodic distribution payments and the dissolution amount at the end of the transaction’s tenure. Using the proceeds from the sukuk, the SPV is then able to enter into a wakalah (agency) agreement with a third party, the wakeel, who will then invest the funds entrusted to him in a pool of wakala assets, the specifics of which are agreed upon in advance by the investors, the originator, the SPV, and the wakeel. It is crucial that the necessary details of the wakalah assets be specified to the greatest extent possible in all legal documents relating to the assets concluded between the four main parties to the wakalah transaction and the sukuk issuance. The fundamental criterion for the assets is that they not be related to profits gained from Shariah-prohibited activities.

However, the wakeel’s investment in these assets is not a direct process. The wakeel first purchases the assets from another third party, the seller. Once he owns the assets, he can then exploit them for maximum profit. The somewhat convoluted process is an attempt to comply with another principle in Islamic finance: the concept that one cannot trade in assets that he does not already own, or be almost certain that he will own. Hence, the basis of the transaction is that the SPV is selling ownership stakes in assets that the wakeel will purchase and invest on behalf of the SPV. The order in which the documents are concluded bears additional gravity to the situation. The SPV must sign the wakalah agreement with the wakeel before the wakeel purchases the assets; otherwise, the wakeel would have purchased the assets on its own behalf, not on behalf of the SPV, and the SPV would have sold the investors assets that it did not actually own, erasing the intended Shariah-compliant nature of the transaction. It is incumbent on financial institutions wishing to issue sukuk that they respect the proper timing.

As the wakalah assets become profitable and generate regular returns on the investment, the SPV uses those returns to pay the periodic distribution amounts to the investors. The wakeel’s payment comes from the excess in profits after the periodic distribution amount has been paid, which serves to incentivize him to make the strongest and most profitable investment decisions, as his compensation is directly proportional to the quality of his work. The dissolution price is paid to investors upon the conclusion of the transaction’s tenure, which can occur through the SPV activating the clause of the purchase agreement requiring the originator to purchase the assets on that particular date. Or, it can occur earlier, if the originator wishes to purchase the assets prior to the maturity date. The sale price of the assets is termed the “exercise price”,[6] and the sukuk holders are paid the dissolution amount in accordance with that price.

Murabahah Sukuk

The sharp decline in the cumulative value of murabahah sukuk offerings may be due to increased concern over the Shariah-compliance of this structure. Whereas murabahah sukuk were worth US$65.3 billion in 2013, their issuances amounted to a paltry US$12.5 billion in 2015.[7] The most likely reason for this drastic decline, which cannot be explained by the drop in oil prices alone, is that AAOIFI standards do not permit the trading of murabahah sukuk in secondary markets, as these sukuk are closest to debt.[8] The debt-like nature of murabaha sukuk can be derived from the structure of the underlying murabaha transaction, and the relation of the investors to the assets in that transaction as a source of revenue. A murabaha transaction is usually translated as “cost plus” or “deferred price” financing, as it consists of the sale of assets to the customer in exchange for a deferred price. The deferred price is, by nature, greater than the price of the assets themselves. Of course, the difference is charged not through interest, which is prohibited, but through a pre-agreed “cost plus” amount to which the seller is entitled for facilitating the transaction and providing the assets in advance.

As such, following the SPV’s issuance of sukuk to the investors, the investors do not legally own any fungible assets. Rather, they are simply entitled to the proportional share of the deferred price. Murabahah sukuk are justified on the grounds that the debt obligation does not involve the charging of interest, which makes it permissible under the Shariah. Similarly to other sukuk arrangements, the SPV is the trustee of the sukuk proceeds on behalf of the investors. The originator then acts as the buyer, agreeing to purchase assets from the SPV on a cost plus basis, should the SPV acquire the assets. The SPV acquires the assets via purchase arrangement with a third party, using the sukuk proceeds as funding for the transaction. The purchase price of the assets in the SPV-third party transaction is then assessed as the delivery cost, the principal, of the transaction between the SPV and the originator. The tenure of the sukuk is determined by the length of time allocated for the payment of the deferred price. Rather than pay the deferred price as a lump sum at the end of the sukuk’s tenure, the originator pays the deferred price to the SPV in regular installments, which are then paid to the investors as the periodic distribution amount. The Shariah-compliance of this type of sukuk transaction is based in the reality that the investors are not possessing debt per se, but are actually possessing a right to a deferred price to which they are entitled following the sale of assets purchased on their behalf, using their liquidity.

Ijarah Sukuk

Notwithstanding the increasing value of wakalah sukuk issuance, 2015 survey statistics show that ijarah sukuk are still the preferred form of sukuk for a plurality of issuers and investors (24% and 23% respectively).[9] Although ijarah sukuk do not allow the issuer to have a diverse portfolio of Shariah-compliant assets, the underlying transaction is as simple as the wakalah transaction, while being less risky. The increased value of wakalah transactions can thus be explained as permitting greater profit margins than ijarah transactions, which justifies the increased risk if issued in large amounts with significant subscription rates. Unlike murabahah sukuk, there are no doubts as to the Shariah-compliance of the ijarah sukuk; as long as the investors become legal owners of the tangible assets underlying the ijarah transaction, and the ijarah sukuk can be traded on secondary markets.[10] Investors obtain rights to periodic distribution payments and the dissolution amount in accordance with their ownership of the asset. The SPV uses the sukuk proceeds to buy assets from the originator on behalf of the investors. These assets are then leased back to the originator for a lease period corresponding to the sukuk’s tenure. During the lease period, the originator must abide by the service agreement compelling him to undertake regular maintenance of the assets, to protect the investment from depreciation or destruction. Once the originator repurchases the assets, whether at the conclusion of the lease period or due to his exercise of an option in the sale agreement, the exercise price is paid to investors proportionally in accordance with their ownership percentage of the asset.

Legal Documentation of Sukuk Transactions

Legal documents for sukuk transactions can generally be classed into several categories: agreements between the investor and the SPV, agreements between the SPV and the originator, agreements between the SPV and third parties (whether wakeel, supplier, seller, etc.), agreements between the originator and third parties, and supporting documents detailing the conditions of the sukuk, whether for legal or tax purposes. This section will discuss the legal specifications of the sukuk offering as presented to potential investors, as well as those pertaining to the ijarah agreement as an example of documentation for the underlying transaction. All agreements must not only comply with the principles of Shariah, but they must be valid and actionable under the law of the country in which the sukuk are issued.

Sukuk Offering

The sukuk offering contains the percentage of the issue price, the year in which the sukuk reach their maturity, and if applicable, dates in which the investor can exercise the option to redeem his sukuk certificate in advance of the maturity date. Furthermore, it explains the conditions of the subordinated certificates; descriptions of the SPV, issuer, bank, and assets, with additional information regarding the asset quality; principle shareholders, management, and capital adequacy; an explanation of the country’s financial system for foreign investors; tax considerations; and the conditions of subscription and sale. The impetus behind the sukuk offering is to provide the investor with as much information as possible before he invests his funds in the purchase of the certificate.

The risks of the sukuk are clearly explained in a section entitled “Investment Considerations”, while the investor is made aware of the SPV’s limitations and the permissions in accordance with which it may act. In a sample offering, it was noted that the issuer could not allow the redemption of the certificates except with written permission from the originator, which happened to be an Islamic financial institution. In regards to the issuance of the certificates themselves, the offering must inform the investor under which national or international financial authority the sukuk were issued, for both legal recourse and tax purposes, as well as specific legal codes that do not govern the sukuk; to prevent the investor from advancing legal claims regarding the sukuk ownership under codes that may be unfavorable to the issuer or the originator, or which do not govern sukuk effectively. The investor is also apprised of the lead managers of the offering, which tend to be international banks with experience in arranging sukuk issuances, such as HSBC.

The value of the sukuk offering must be specified in terms of amount and currency denomination, along with the relevant deposit information for the customer’s funds once the certificate has been purchased. If the sukuk’s currency differs from the country’s national currency, the sukuk offering will usually contain a historical pattern of exchange rates for a similar period to the sukuk’s tenure, while reminding the investor that any forward statements regarding exchange rates or any other element of the transaction are merely expectations, and as such, may not be correct. This relevant financial information is supplemented by the foreign exchange risk data, which comprises the foreign currency assets and liabilities of the issuer and the bank, concluding with the net structural position of each. The bank’s data is then classified by sector and by geographical region, with a separate section on the bank’s Islamic finance operations. The bank’s non-interest income should always be highlighted.

Potential investors will also be apprised of their earnings, in the event of their purchase of a sukuk certificate. The earnings per share are calculated based on quarterly, biannual, and annual net profits, divided by the weighted average number of ordinary shares, as anticipated by the issuer and the originator. If, as a consequence of high demand, the offering is oversubscribed and the issuer then decides to issue an additional number of sukuk, this earning per share calculation may be adjusted in future documents. Of course, the offering distinguishes between the basic earnings per share and the diluted earnings per share. The diluted earnings per share adjusts the weighted average number of issued ordinary shares for the number of potentially issued shares, factoring in the effects of the share option. The diluted earnings per share is thus, slightly less than the basic earnings per share amount. In tandem with the description of the earnings, the potential investors are supplied with the tax information that may apply to the sukuk under the laws in which the sukuk are issued. This tax information may include the presence of capital gains taxes, a gift or inheritance tax, relevant duties and registration fees, and the legal consequences or permissibility of withholding taxes.

The offering will also give a summary of all relevant documents to the transaction. These typically include the trust deed, the agency agreement, the SPV-Issuer purchase agreement, the management agreement, the purchase undertaking deed, the sale undertaking deed, and the costs undertaking deed. Following this summary, it will detail the obligations of each of the parties under the various agreements, as well as the timing according to which the agreements be concluded relative to each other. Every relevant party will be identified in the offering document; not only the issuer, trustee, SPV and bank; but also the legal advisers, auditors and listing agents.

The offering may also impose some obligations on the recipients. For example, if the offering is sent electronically, then the recipient’s acceptance of the email and viewing of the offering circular is equivalent of his representation of himself as fulfilling all of the eligibility requirements for the offer. The recipient may not forward the offer to any address or person in a country that has been expressly mentioned in the offering as not having jurisdiction over the sukuk offering. Failure to comply with these obligations nullifies the recipient’s capacity to accept the offer and purchase a sukuk certificate in the future. The drafters of the offering will be certain to note that the sukuk offering is neither an offer to sell nor an offer to buy; nor should the recipient reply to the offer directly in order to purchase sukuk certificates, as the purchase must take place as a transaction directly between the investor and the SPV. The careful drafter will also make sure to emphasize that any viruses or malware that might possibly be attached to the email are not the fault of the sender; the recipient is responsible for protecting his own electronic devices, and the sender is not responsible for any damages that may occur as a result of the recipient’s own negligence.

Ijarah Agreement

If the underlying transaction of the sukuk is ijarah financing, then an ijarah agreement will be concluded between the SPV in its capacity as the trustee, and the originator. The ijarah agreement will identify the parties and specify the assets subject to the transaction, along with their relevant features and identifying details, if needed. The originator, as the lessee, will accept the conditions of use imposed the trustee as the lessor, while agreeing to perform all regular maintenance, repairs, and insurance documentation for the assets. The lessor, in contrast, is responsible for insuring the assets, and in the case of damage to the assets resulting in an insurance reward, the lessor alone is entitled to that reward.

In the case of extraordinary events resulting in damage not resulting from the lessee’s fault or negligence, the lessor will bear the financial responsibility of the repairs. The lessee must also permit the lessor’s representatives to have regular access to the assets to examine them and confirm their status. This clause is especially relevant when the ijarah transaction is the basis of sukuk. The SPV is not only acting as a lessor, but as the trustee of the assets entrusted to him by the investors that he has purchased, and then leased, on their behalf. Should the assets depreciate in value or be irreversibly damaged, there would be no profit for the investors. The value of the deposit and the lease payments are explicitly outlined in a schedule, with an appointed payment date, with the posting of payments earlier, should the payment date fall on a business day. Additionally, the lessee must pay all necessary administrative fees and taxes necessary for the licenses required to operate or possess the assets.

Finally, all primary concerns for investors are addressed in the ijarah agreement. If, for some reason, the assets are used for criminal activity, or they are operated in a way that causes damages to a third party, then the originator is the only responsible party for the damages or the legal ramifications of the criminal activity. The ijarah agreement stipulates that if the originator enters bankruptcy or liquidation proceedings, and is rendered unable to pay the lease payments on the time, or at all, then the SPV is entitled to repossess the assets. The assets cannot be liquidated along with the originator’s other assets, nor can they be used as collateral in the fulfillment of separate debt obligations.

GCC Sukuk in an Age of Low Oil Prices

The Global Sukuk Market

The global sukuk market is concentrated in Southeast Asia and in the GCC. Malaysia is the worldwide leader in sukuk issuances, although GCC members have rapidly expanded their presence in this market. While the US Islamic finance sector is underdeveloped, the US Dollar is the preferred denomination in which to issue sukuk. The UK and Luxembourg, two of the premier European financial centers, entered the sukuk market with sovereign issuances in 2014. The Luxembourgish issuance is especially noteworthy because it represents the first euro-dominated sukuk issued by an EU-member country.

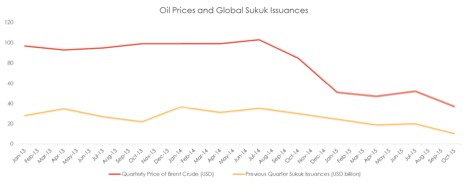

In light of this theoretical, legal, and global framework, it is now possible to discuss the practical application of the sukuk market in the GCC. In a recent survey, 62 percent of purchasers expressed negative expectations regarding sukuk as a result of the drop in oil prices.[11] Concrete evidence supports this proposition as well. In 2014, US$114 billion worth of sukuk were issued; whereas the first three quarters of 2015 only witnessed the issuance of US$48.82 billion of sukuk.[12] When this data is compared to the same point in 2014, the difference is stark. By the end of the third quarter of the 2014 fiscal year, US$99.27 billion in sukuk had been issued. One can argue that the drop in oil prices reversed a formerly positive trend in sukuk issuance. The sukuk issuance for 2014 was 24.5 percent higher than the previous year; whereas the 2015 sukuk issuance was 50 percent lower than that of 2014. Even accounting for the Central Bank of Malaysia’s decision to freeze its sukuk issuances, apparently the drop in oil prices created uncertainty among potential investors, who were reluctant to invest in what is essentially a niche financial market with inconsistent regulation.

Given that, most recently, an attempt in Doha to fix oil prices failed, the price of oil stubbornly refuses to increase. One place where low oil prices are perceived to impact the financial sector is through reduced sukuk issuances. Standard & Poor’s, reflecting the expert consensus, predicts that low oil prices will dampen sukuk issuances. We decided to test this consensus using data assembled from Google Finance, Kuwait Finance House, Malaysia International Financial Centre, and Standard & Poor’s. We believe that the chart below is first chart comparing historical oil prices and sukuk issuances.

This chart suggests that there is a correlation between reduced oil prices and reduced sukuk issuances. In examining the two, one cannot forget that Malaysia, the worldwide leader in sukuk, which is not usually considered a petroleum-reliant economy, still receives roughly 30 percent of government revenue from Petronas, its state-owned oil company. Other leaders in sukuk, especially those in the Gulf Cooperation Council, are also heavily reliant on oil revenues.

GCC countries have responded to the decline in oil prices and the contraction of the sukuk market by turning to conventional bonds. Saudi Arabia, for example, has expenditures on multiple fronts. It provides foreign aid to less fortunate neighbors such as Egypt. It is heavily invested in military expenditures to oust Iran-backed Houthi rebels from adjoining Yemen, while propping up the weak Sunni government. This is not to mention the costs of maintaining the living standards of the extended royal family and maintaining Saudi Arabia’s image as a successful, cash-rich provider of funds. This image is essential to Saudi Arabia’s regional influence, especially as Iran re-enters the international community. Last summer, for the first time since 2007, Saudi Arabia issued SAR20 billion (US$5.33 billion) in development bonds that are set to mature over varying lengths of time.[13] In contrast, Saudi Arabia’s last sukuk issuance was for only SAR2.7 billion (US$720.12 million) of perpetual sukuk.[14] Saudi Arabia’s actions demonstrate a lack of confidence in the potential of sukuk as a reliable tool for long-term infrastructure financing.

This is not to say that all actors in Gulf countries are demonstrating the same reluctance. Prior to Saudi Arabia’s decision to issue bonds, Emirates Airlines in the UAE issued US$913 million of ijarah sukuk with a ten year tenure,[15] with the objective of funding the acquisition of additional aircraft and expanding the airline’s operations. Emirates Airlines’ initiative is reflective of Dubai’s positive stance towards sukuk as well, given the close ties between the emirate’s transportation center and the government of Dubai’s sole international airline.

One of the issues seems to be a lack of coordination between GCC countries on their sukuk policies, with each state independently issuing sukuk geared toward its own narrow financing objectives. Sovereign sukuk in the GCC comprised 29 percent of the total value of sukuk issuances in the region, as opposed to the 8 percent that were quasi-sovereign during the period from August 2014 until August 2015.[16] In addition to the Emirates Airlines sukuk mentioned in the previous paragraph, other quasi-sovereign entities that have issued sukuk include the Saudi Electricity Company and Saudi Telecom. Lead arrangers and issuers have historically preferred sovereign and quasi-sovereign sukuk, presumably due to the explicit or implied backing of a government for these structures.

GCC Sukuk Performance Expectations, Analysis, and Predictions

GCC sukuk, while exposed to the same international stresses as those in other regions, also suffer from a unique set of factors. As opposed to the bond market, where there is active trading of debt securities, sukuk are held by a small number of investors, who tend to follow a buy-and-hold model of investment. This means that there is no equivalently active secondary market to provide liquidity. If GCC countries were to issue sovereign sukuk in 2016, in separate tranches with ten and fifteen year tenures, these funds could not only be used to fund financial infrastructure, but they would provide the international community a means through which to launch the rebuilding of war-torn areas, without concentrating the burden on any specific country.

Furthermore, while the AAOIFI is located in Bahrain, and their Shari’ah and accounting standards have been promulgated nationally in countries such as Pakistan, many countries do not have sufficient sukuk standards and regulations. This lack of national standards is compounded by the lack of universally-acceptable standards. Given that there is wide diversity within Islam, it follows that there is wide diversity in approaches to Islamic finance, including sukuk, so worldwide standardization will be challenging. However, through integrating the AAOIFI into a larger GCC, or preferably worldwide, regulatory body for sukuk and Islamic finance, the Gulf could not only reposition itself as the investment capital for sukuk, but as the regulatory center as well. This possibility appears slightly more realistic in light of the contraction of the Malaysian sukuk market. Unfortunately, should the GCC countries not take these steps, it remains likely that smaller GCC states will take Saudi Arabia’s lead, and resort to bonds rather than sukuk. This step, in what is considered to be the ideological fulcrum of the Muslim majority world, could further reduce confidence in sukuk as a viable investment and financing initiative.

Although historically sukuk issuances and oil prices have been correlated, there are several pathways suggesting that this could change. Perhaps an acceptance of reduced hydrocarbon revenues would lead GCC governments to seek alternative funding pathways, which presumably would include an increase in sovereign sukuk. In the long term, sukuk could be backed by any asset, so there is potential for sukuk to be used in connection with alternative forms of energy. These “green sukuk” to finance wind and especially (given the weather in the GCC) solar power could build the sukuk market in the GCC and decouple sukuk issuances from oil prices.

Conclusion

By understanding that sukuk are not simply “Islamic bonds,” one can take a nuanced view of their position of the GCC and global financial markets. The difference between sukuk and bonds is clearer when one follows best practices in preferring Shariah-compliant asset-backed sukuk.

In analyzing the most common structures for sukuk, one observes how the balance between investors’ goals and Shariah-compliance leads to complexity and diversity. The lack of universally-accepted standards creates further complexity, and the potential for confusion. Due to this complexity and diversity, it is imperative that sukuk offerings provide appropriate investors with all needed information.

Historically, sukuk offerings and oil prices have moved together. In 2015, sukuk offerings took two major blows from the Central Bank of Malaysia’s pause on new issuances and sustained low oil prices. In response to the second blow, Saudi Arabia returned to conventional debt markets in 2015. It remains to be seen if other GCC countries follow the Saudi lead.

One bond issuance does not signal the beginning of the end of the GCC sukuk experience. Sukuk can be backed by any permissible asset, so there are opportunities for environmentally-conscious energy projects in the GCC to revitalize the sukuk market.

Walid Hegazy has over 20 years of legal experience representing and advising clients on transactions and disputes involving the commercial laws and regulations of many Middle East countries, including Egypt, the UAE, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Libya. Dr. Hegazy’s main areas of expertise include Islamic banking and finance, project finance, corporate restructuring and corporate governance. He has SJD (Doctor of Juridical Science) and LLM degrees from Harvard Law School.

His representative experience includes advising a major Saudi real estate investment group in connection with a SR1 .2 billion Murabaha facility; advising a major Saudi real estate developer in connection with structuring and documentation of Shari `ah-compliant facilities for the financing of a mix use real estate project in Mecca; advising Credit Suisse on a US$1.2 billion lease-backed securitization based in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, in which he developed an innovative Shari `ah-compliant structure based on the Islamic contract of Hawala (assignment of debt). He has written extensively on Islamic finance in a number of academic journals. Before launching Hegazy & Associates, Crowell’s affiliated law firm in Cairo, Dr. Hegazy was heading the Islamic Finance Practice Group at the international law firm of Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer (Dubai, UAE and Riyadh, KSA). The other international law firms at which He practiced law include: Fulbright & Jaworski (Houston, TX), Baker & McKenzie (Riyadh, KSA), White & Case (New York), Groupe Monassier (Paris), formerly known as “Monassier & Agassi,” and Zaki Hashem (Cairo).

[1] The Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI), in their most recent Shariah Standard No. 17 defines “Investment Sukuk” as “certificates of equal value representing undivided shares in ownership of tangible assets, usufruct, and services or (in the ownership of) the assets of particular projections of special investment activitiesÔǪ”

[2] Quran 2:275.

[3] Reuters, “Most Sukuk ÔÇÿnot Islamic’, body claims”, arabianbusiness.com. Reuters,┬á November 22, 2007. http://www.arabianbusiness.com/most-sukuk-not-islamic-body-claims-197156.html#.V2ppbPl96M8

[4] Thomson Reuters, “Issuance by Structure”, Industry at a Crossroads: Thomson Reuters Barwa Sukuk Perceptions and Forecast 2016, p. 7.

[5] Thomson Reuters, “Sukuk Structure Growth Comparison (2014- Q3, 2015)”, Industry at a Crossroads:Thomson Reuters Barwa Sukuk Perceptions and Forecast 2016, p. 36.

[6] Islamic Banker, “Sukuk Al Wakalah”, islamicbanker. https://www.islamicbanker.com/education/sukuk-al-wakala

[7] Thomson Reuters, “Sukuk Structure Growth Comparison (2014- Q3, 2015)”, Industry at a Crossroads:Thomson Reuters Barwa Sukuk Perceptions and Forecast 2016, p. 36.

[8] AAOIFI Shariah Standards.

[9] Thomson Reuters, “Survey Findings-Structure Preference”, Industry at a Crossroads: Thomson Reuters Barwa Sukuk Perceptions and Forecast 2016, p. 36.

[10] AAOIFI Shariah Standards.

[11] Thomson Reuters, “Survey Findings ÔÇô With the Drop in Oil Prices, Do You Think Sukuk Performance Will”, Industry at a Crossroads: Thomson Reuters Barwa Sukuk Perceptions and Forecast 2016, p. 51.

[12] Thomson Reuters, “Global sukuk growth for the first 9 months (2011-2015)”, Industry at a Crossroads: Thomson Reuters Barwa Sukuk Perceptions and Forecast 2016, p. 24.

[13] Ahmed Al Omran, Nicolas Paraisie, “Saudi Arabia Issues Bonds Worth $5 Billion to Plug Budget Shortfall”, The Wall Street Journal. ┬áAugust 11, 2015. http://www.wsj.com/articles/saudi-arabia-issues-bonds-worth-5-billion-to-plug-budget-shortfall-1439305126

[14] Sukuk Database, “National Commercial Bank (Perpetual)”, Sukuk. 2015. https://www.sukuk.com/sukuk-new-profile/national-commercial-bank-perpetual-4697/

[15] Sukuk Database, “Khadrawy Limited”, Sukuk. 2015. https://www.sukuk.com/sukuk-new-profile/khadrawy-limited-3935/

[16] Rasameel Market Finance, “Sukuk Issuance by Value, Number, and Type”, GCC Market Update. https://www.sukuk.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/GCC-Market-Update-August-2015.pdf