CLICK HERE FOR THE PDF

Editor’s Introduction

Strategic competition in the Middle East tends to be narrowly defined by military capacities: because of the recurrence of conflicts in the region, we too often look at tanks, missiles, and fighter jets as the most reliable indicators of power. Where observers go beyond these to scrutinise developments at sea, their focus is only on the naval element, notably, whether the US navy is in retreat from the Middle East, now that it is no longer dependent on energy supplies from the region, and whether the Chinese navy has developed a blue water capability that allows extended deployments into the region.

However, this security-centred perspective misses an important, and too often forgotten, dimension of the Middle East: the Persian Gulf region remains a major source of the world’s seaborne energy supplies, accounting for 34% of global oil exports in 2020 and 26% of liquefied natural gas exports.[1] Meanwhile, the development in recent decades of offshore gas exploration projects in the Mediterranean region has generated new economic interest, both from regional and international players: it is already changing the profile of a country like Israel, which has now become energy independent and is a modest gas exporter. The region could in the future help Europe in its quest to diversify its gas supplies as it seeks to decrease its reliance on Russian supplies.

Adding to the importance of energy resources is the geographical location of the Middle East, which makes it a major transit zone for maritime trade. Commonly understood as an area that ranges from Egypt to Oman, the Middle East is a gateway between Europe, Asia, and Africa. From the Gulf of Oman and the Arabian Sea, it is also a gateway to the high waters of the Indian Ocean, exposing countries along the littorals to the great power competition that is taking place there.

Given these characteristics, the Middle East has in recent years witnessed a surge of projects, launched either by the littoral countries or external powers, to exploit the newfound offshore gas reserves and the shipping and logistics opportunities that open up as global maritime trade grows. These involve massive investments in offshore gas exploration, expansion of port capacities, and shipbuilding. In the past decade, countries like Israel and the United Arab Emirates, for instance, have funded such initiatives as they seek to become maritime powers.

But those ambitions are challenged by local issues that chronically affect maritime security: piracy and terrorist attacks in the waters between the Suez Canal and the Strait of Hormuz have long been a problem for merchant ships and frequently prompt insurance companies to raise their premiums for vessels plying those waters. The wave of attacks targeting tankers in the Gulf of Oman in May 2019 was a stark reminder of the security risks facing maritime traffic in the region.[1]

Notwithstanding these traditional security challenges, the region has become an arena of fierce competition among local powers aiming to position themselves as the uncontested hub for maritime freight. This has caused a frenzied construction of gigantic port infrastructures, notably in the UAE, Qatar, Oman and Saudi Arabia, a development that reflects less the demands of global shipping than local ambitions, which begs the question of overcapacity, redundancy and, consequently, the long-term survival of such projects.[2]

**********

Against this backdrop, this volume of Insights aims to investigate how both Middle Eastern countries (notably, Israel, the UAE and Turkey) and external powers (namely, Europe, China, and India) are planning and conducting their maritime strategies in the region. “Maritime strategies” is understood here as economic policies designed by states in coordination with private operators (port management entities, shipbuilders, and shipping companies). Specifically, this collection of essays explores how countries and their major private maritime players envision their maritime strategies for the region.

Overall, the articles highlight the absence of one uncontested maritime power: the United States. If the United States remains the primary naval power in the Middle East — thanks to the US Navy’s Fifth Fleet operating from the kingdom of Bahrain — it does not have the same maritime ambitions as India, China, or the European countries. In the past two decades, the United States has drastically decreased its consumption of Middle East energy: in 2021, only about 9% of US crude oil imports came from the region.[3] Meanwhile, since much of US trade with Asia uses trans-Pacific shipping routes, the United States does not see the Middle East as a gateway to Asia like Europe does.

As a result, the nature of competition in the Middle East is quite different from that observed in Asia. Rather than being a theatre of great power competition, the Middle East is a fragmented landscape made up of small and middle local powers (e.g., Israel, UAE, Turkey) seeking greater roles at sea and external powers (China, India, Europe) trying to secure their share of influence — with varying degrees of success.

**********

Is India a Maritime Player in the Gulf?

The volume begins with an article by Frederic Grare that explores the determinants of India’s greater naval involvement in the Gulf region and asks a critical question: Is India a maritime player in the area? Grare’s assessment calls for caution: the maritime profile of India reflects as much the strengths of the country’s economy as its weaknesses. In other words, India does have an obvious interest in securing its access to the Gulf but its struggle to mount a full-fledged maritime security role in the region shows important resource limitations. Middle Eastern dynamics also play a role in India’s inability to significantly increase its maritime profile in the region, with India often getting caught in the rivalry between Iran and the Arab Gulf states.

From Haifa to Abu Dhabi: China’s Maritime Strategy in the Middle East

The second article, authored by Jonathan Fulton, investigates China’s maritime presence in the Middle East, from its involvement in the expansion of Israel’s Haifa port to its growing investments in the UAE’s Khalifa port free trade zone and Khalifa industrial zone in Abu Dhabi. Fulton notes that the European Union’s importance as a trade partner for China has made maritime connectivity across the Persian Gulf and Mediterranean Sea a crucial component of the country’s Belt and Road Initiative. In that context, Beijing’s maritime activism in the Middle East is the result of a coherent policy framework that aims to develop a presence in ports and industrial park complexes across the region. Fulton contends that Beijing’s current interest in these port cities is largely commercial rather than military although it has aroused suspicions in the United States, which has dense security relations with most of the Middle Eastern countries concerned.

European Maritime Strategies for the Middle East: Struggling for Relevance?

In the third contribution, Daniel Fiott questions the relevance of European maritime strategies towards the Middle East. As major trading nations, the Europeans are highly dependent on maritime routes and the hubs and ports along the Suez Canal, Red Sea, Gulf of Aden and the Mediterranean. The Middle East is in itself important as a source of European imports and destination for European goods. But, as Fiott notes, despite the obvious need for a robust European posture at sea to protect their commercial interests, lack of unity and conflicting priorities, from the war in Ukraine to Europe’s growing pivot towards the Indo-Pacific, leave Europe dithering and unable to allocate the much-needed resources to the Middle East. As a result, the European Union’s maritime strategy shows a worrisome disconnect between intent and capabilities.

Thalassocracies in the Making: The Case of the UAE and the Western Indian Ocean

The fourth article, written by Brendon Cannon, looks at the emerging maritime ambitions of the UAE and ponders whether the small Gulf state is becoming a “thalassocracy”, i.e., a political entity that uses its naval and/or merchant fleet to assert its power and unite possessions separated by water. Drawing a comparison with a historical example, that of Oman in the 18th and 19th centuries, Cannon notes that the efforts of Dubai’s port operator, DP World, to refurbish and expand a string of ports in the Red Sea and Horn of Africa have not yielded political influence for the UAE’s political leadership. He provides a cautious conclusion: Abu Dhabi may seek a greater role at sea but as of now its capabilities — either civilian or military — are too limited to fulfil those ambitions.

East Mediterranean Gas Discoveries and their Strategic Impacts

In the final article, Ehud Eiran delves into the details of offshore gas discoveries in the East Mediterranean Sea since the late1990s. Eiran acknowledges that these discoveries have changed the economic prospects of countries like Israel, Egypt, Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey. But after years of exploration, the initial optimism has been replaced by caution: extracting natural gas in the Mediterranean has demanded costly investments that took time to deliver. Furthermore, the economic output from the discoveries may have ushered in cooperation among littoral states but they have also fuelled tensions, be it between Turkey and Cyprus, or most recently between Israel and Lebanon.

**********

Together, the articles in this volume provide a snapshot of the ever-evolving maritime landscape in the Middle East. Given the volatility and the depth of the topic, the collection is not meant as a definitive account of maritime competition in the region. Instead, it was conceived as an initial contribution aimed at fostering academic and policy discussions on a much too often neglected topic.

Jean-Loup Samaan

Senior Research Fellow

Middle East Institute, National University of Singapore

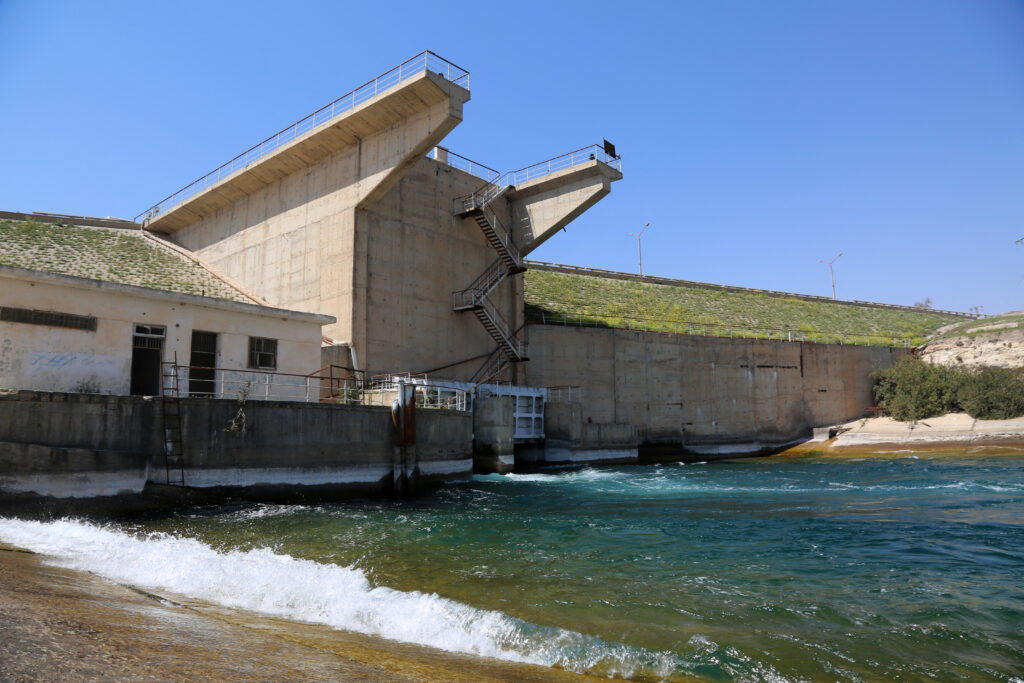

Image Caption: A Danish-flagged container ship crossing the Suez Canal, 5 October 2012. AFP.

End Notes

[1] BP, “Statistical Review of World Energy — 2021”, https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2021-middle-east-insights.pdf

[2] BBC, ”Four Ships ‘Sabotaged’ in the Gulf of Oman Amid Tensions”, 13 May 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-48245204

[3] Eleonora Ardemagni, “The Age of Ports: Gulf Monarchies and Sea Rivalry”, Aspenia Online, 29 March 2018, https://aspeniaonline.it/the-age-of-ports-gulf-monarchies-and-sea-rivalry/

[4] US Energy Information Administration, “Oil and Petroleum Products Explained”, https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/oil-and-petroleum-products/imports-and-exports.php

More in This Series

- Jean-Loup Samaan

- - October 15, 2024