Series Introduction

Maritime Strategies in the Middle East

The Middle East is a major area of maritime trade, given the vast oil supplies in the Persian Gulf region and several gas exploitation and exploration projects in the Mediterranean. The development of these prospects and maritime trade, however, are threatened by acts of piracy and terrorist attacks in the waters between the Suez Canal and the Strait of Hormuz. Such threats have frequently prompted insurance companies to raise their premiums for merchant ships that navigate these waters. In addition, the Middle East has been the arena of fierce competition not only among the external actors who have economic and strategic interests in the region but also among local powers aiming to position themselves as the uncontested hub for maritime freight. The papers in this series of Insights explore how the countries of the Middle East and key external actors envision their maritime strategies for the region.

CLICK HERE FOR THE PDF

By Jonathan Fulton*

This article explains how the Middle East features in the maritime component of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Beginning with a discussion of the region’s utility for the BRI, it then describes how China applied an existing model — the Shekou model — to develop a presence in ports and industrial park complexes in six regional countries: the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Djibouti, Egypt, and Israel. These commercial projects provide China with port access in strategically important cities from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea, supporting its maritime economic and strategic ambitions while at the same time contributing to host countries’ development agendas.

The announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013 was a major turning point in China’s foreign policy, as well as an indicator of its deepening political and economic engagement with participating countries.[1] Of the first two components of the BRI, the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) and the Maritime Silk Road Initiative (MSRI), the latter is of far greater significance in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).[2] Given the European Union’s importance as a trade partner for China, maritime connectivity across the Persian Gulf and Mediterranean Sea is a crucial element of the BRI. Consequently, Beijing has focused on developing a deeper presence in several MENA port cities over the past decade.

China’s regional engagement has been largely focused on economic benefits rather than strategic concerns. This is consistent with what Sun and Zoubir describe as an economic diplomacy “embedded in its business-first strategic culture, i.e., making economic development the priority of the government’s tasks”.[3] Chinese officials too emphasise this perspective when discussing the BRI; President Xi Jinping asserted that it is “not a tool to advance any geopolitical agenda, but a platform for economic cooperation”.[4] This statement deserves a critical response. There are political and normative values underpinning any project, and they will undoubtedly serve geopolitical goals, directly or indirectly. Regardless, for the time being, China’s approach to these port cities has been commercial rather than military, although China did open its first overseas base in Djibouti in 2017.

The Middle East in China’s Maritime Ambitions

The BRI is primarily a series of projects designed to connect and integrate cooperating partners — cities, markets and countries — across regions, and therefore a partner’s degree of connectivity plays a larger role than factors like its regime type or market share. In the case of MENA countries, this means that a favourable geopolitical location and integration into key facets of the global economy are important indicators of utility in Beijing’s regional policy. Iran, for example, is a potentially major economy with a strong state, a large market and a coastline that could provide China with overland access to the Gulf. However, its political and economic isolation make it a less useful MSRI partner, and China has so far done little in the realm of ports or industrial parks in Iran. One could make the point that Iran is an outlier given the unique range of factors at play in its case, but in fact it is a striking example of how circumstances can prevent several countries with otherwise favourable endowments from benefiting from the MSRI. Yemen, Syria, Lebanon and Libya would all be obvious candidates for Chinese port investments, but due to political instability, insecurity, or both, they are bypassed.

During the 2018 China-Arab States Cooperation Forum, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi announced a framework for MENA countries to partner in MSRI: the “Industrial Park–Port Interconnection, Two-Wheels Two-Wings Approach” (henceforth 2W2W).[5] Here, the “two wheels” are energy cooperation (conventional oil and gas and low-carbon energy) and the “two wings” are cooperation in technology (artificial intelligence, mobile communications, and satellite navigation) and investment and finance. This is fundamentally similar to the Shekou model, or “Port-Park-City” development model, developed by China Merchants Port Holdings and used to great effect in Chinese economic free zones such as Shenzhen, as well as in China’s economic engagement in Southeast Asia.[6] The Shekou model “entails developing adjacent industrial parks, commercial buildings, highways, free trade zones, residential area, and power plants” with the goal of developing “a larger, integrated system that helps sustain the port and is sustained by it in turn”.[7] In MENA’s case, the 2W2W emphasized four ports where China would increase its presence, and four industrial park projects at varying stages of development. The ports are:

- Khalifa Port Free Trade Zone (KPFTZ) in Abu Dhabi,

- Oman’s Port of Duqm,

- the support base of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) in Djibouti, and

- Port Said in Egypt.

The industrial parks are:

- Khalifa Industrial Zone Abu Dhabi (KIZAD),

- the China-Oman Industrial Park in Duqm,

- the Chinese Industrial Park in Saudi Arabia’s Jizan City for Primary and Downstream Industries (JCPDI), and

- the TEDA-Suez Zone in Ain Sokhna, Egypt.

Since this initiative was announced engagement across the eight projects has been uneven, with some enjoying significant momentum, others seemingly stalled, and other, non-2W2W ports or parks in the region becoming more significant in Beijing’s MENA presence.

Abu Dhabi, UAE

China’s political and economic presence in Abu Dhabi has increased dramatically since 2015 when its crown prince and the UAE’s de facto ruler Mohammed bin Zayed al Nahyan made a state visit to Beijing.[8] Previously, Dubai was the anchor of the China-UAE relationship with the largest Chinese expatriate community in MENA, estimated between 270,000 and 300,000, over 5,000 Chinese businesses, and more than 200 Chinese companies with regional headquarters based in the Jebel Ali Free Zone (JAFZA).[9] Dubai continues to be a major centre of Chinese social and economic influence in the region; Dubai’s ruler Mohamed bin Rashed al Maktoum travelled to Beijing for the Belt and Road Forum in 2019 and signed US$3.4 billion worth of deals for Chinese investment in JAFZA.[10] However, as the China-UAE relationship has grown to include more strategic considerations, the capital city of Abu Dhabi has come to play a more prominent role.

This is evident in the deeper levels of Chinese engagement in the KIZAD/KPFTZ complex. In 2016 China’s COSCO Shipping signed a 35-year concession agreement with KIZAD, an investment valued at US$738 million that doubled the container handling capacity of the port.[11] In early 2018 a consortium from Jiangsu province announced that over 15 Chinese companies had signed deals in KPFTZ worth over US$1.1 billion across the construction, manufacturing, and trade and logistic sectors.[12]

China’s involvement in Khalifa Port took an interesting turn in 2021, when the Wall Street Journal reported that China was building a military facility there.[13] This was followed by a burst of activity in Washington: a congressional hearing was held that August that explicitly discussed the strategic implications of China-UAE relations, with a Pentagon official, Dana Stroul, saying, “We understand that there will be an economic or trade relationship with China, just like the United States has, but there are certain categories of activities or engagement that our partners may be considering with China that, if they do, will pose a risk to US defense technology, other kinds of technology, and ultimately force protection.”[14] US officials warned that a Chinese military presence in the Emirates would jeopardise the proposed sale of F-35 fighter aircraft to the UAE.[15] Emirati officials, for their part, publicly voiced concerns about how US-China competition adversely affects their interests.

Subsequently, in November 2021 the Wall Street Journal reported that construction of the Chinese facility had been stopped,[16] although Emirati officials denied that there was a military purpose; presidential adviser Anwar Gargash said, “The UAE’s view was that these certain facilities in no way could be construed as military facilities.”[17] Shortly after the UAE announced it was no longer pursuing the F-35 deal, claiming concerns of “technical requirements, sovereign operational restrictions, and cost/benefit analysis.”[18] Whatever role Chinese involvement had in the deal collapsing, it is clear that the United States has real concerns about China-UAE ties advancing beyond the economic realm. It is worth noting that in February 2022 the UAE announced that it was planning to buy a dozen L-15 jet trainers from the China National Aero-Technology Import and Export Corporation, with the possibility of expanding the deal to 36 jets.[19]

Duqm, Oman

Duqm is a port on Oman’s long Arabian Sea coastline, making it an especially attractive project. An industrial/energy/shipping complex here, if connected to other Arabian peninsula cities and facilities, would offer an alternative access point to Gulf energy that is not reliant on the Hormuz Strait. This would allow Gulf energy producers to lessen their vulnerability to Iranian threats to close that major chokepoint. To this end, the Omani government has been trying to access foreign capital since the early 2000s to develop the port/park complex.[20] To this end, the MSRI offered an opportunity, based on long-standing economic relations between China and Oman.

In 2017, Chinese firms, mostly from Ningxia province and in cooperation with the PRC government, signed several major MoUs with the Duqm Special Economic Zone Authority (SEZAD). This complex includes both Duqm port and the China-Oman Industrial Park, which was designed to house the many projects agreed to in the MoUs. The announced projects included a US$2.8 billion contract to build a methanol plant, US$406 million for a power plant, and a US$94 million solar panel plant.[21] Other projects would include residential housing complexes, schools, and retail complexes. All told, the commitments totalled US$10.7 billion, representing a major potential Chinese presence.[22]

Since then, however, there has been little momentum. Initial projections had 30 per cent of the Chinese projects being completed by 2022, but the first factory in the China-Oman Industrial City opened only in October 2021.[23] What accounts for the chasm between the MoUs and project completion? For one, China’s overseas lending started to drop substantially after a BRI peak in 2016 as its financial institutions’ appetites for risky overseas projects did not match the hype of the BRI.[24] Oman, with a very weak economy, perhaps made less sense as a destination for Chinese foreign direct investment. Omani domestic considerations also may have been at play. Oman’s exports to China represented 46 per cent of its total exports in 2019, creating an uncomfortable dependency.[25] In 2017 the Omani government had to borrow US$3.55 billion from Chinese banks in order to cover the federal budget.[26] This debt, on top of the trade imbalance and large number of Chinese investments, may have been a concern among Omani leaders.

At the same time, the PLAN has long used the Omani port in Salalah for comprehensive replenishment and rehabilitation during its deployment in the United Nations counterpiracy mission in the Gulf of Aden. Early in the mission, Salalah was the port that PLAN ships docked most frequently in.[27] Therefore, support for China’s maritime goals may not require the development of new ports and park facilities in Oman.

Jizan, Saudi Arabia

After signing a comprehensive strategic partnership agreement during Xi Jinping’s state visit in January 2016, a joint venture company, Silk Road Industrial Services, was established by Chinese and Saudi entities to pull investors into the Chinese Industrial Park, housed in JCPDI.[28] Located on the kingdom’s west coast, Jizan offers yet another potentially strategic access point for China’s MSRI ambitions in MENA. It was designated as a key industrial park by the Chinese government, giving the project political weight in the PRC.[29]

As in Duqm, a major comprehensive industrial zone was planned, with heavy and light industrial manufacturing projects as well as residential and commercial projects announced. And, in another commonality with its Omani counterpart, there has been little in the way of completion. At the time of writing, the most significant development has been a US$3.8 billion petrochemicals plant built by Pan-Asia PET Resin Co, a company from Guangzhou.[30] A significant difference, however, is that China and Saudi Arabia have a comprehensive strategic partnership agreement with deep political and economic momentum. The kingdom is consistently China’s largest economic partner in the MENA region and leaders in both countries have articulated plans for deeper policy alignment, meaning there is a much greater likelihood that Jizan projects will come to fruition.

Djibouti

As the site of China’s first overseas military installation, Djibouti is an important component in the PRC’s regional maritime strategy. The PLAN first deployed an anti-piracy task force to the Gulf of Aden/Horn of Africa region in 2008, and in 2017 opened what it referred to as a logistics centre in support of this ongoing mission. Djibouti’s strategic location in a maritime transit corridor that is crucial to Chinese trade, combined with the fact that many other countries have military facilities there, meant that the PLAN’s presence was not unusual, other than for the fact that China had not developed an overseas base before then.[31] China’s 2015 White Paper on Military Strategy emphasized the need to “develop a modern maritime military force structure commensurate with its national security and development interests” and added that the PLAN would play a larger role in protecting strategic sea lines of communication.[32] This was folded into the 2W2W framework the following year.

Ain Sokhna and Port Said, Egypt

The Suez Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone (SETC-Zone) is in Ain Sokhna, on the Red Sea and 120 kilometres from Cairo. Established in 2008, five years before the announcement of the BRI, it has been described as “the flagship project of China-Egypt cooperation within the BRI framework”.[33] Strategically located on the Suez, it has become a major hub for Chinese manufacturing, and China is the largest investor in the Suez Canal corridor. The SETC-Zone is in the process of developing nine industrial zones and Chinese firms have been actively establishing an industrial production base, involving textiles, vehicle manufacturing, and consumer electronics manufacturing. This industrial development is aligned with substantial Chinese construction in Egypt: between 2005 and 2021 Chinese firms earned US$19 billion in construction contracts in Egypt,[34] including the 80-storey Iconic Tower in the central business district of Egypt’s new administrative capital. The SETC-Zone has received foreign direct investment from TEDA Investment Holding Co. Ltd, a Chinese state-owned enterprise.

Haifa, Israel

While not included in the 2W2W framework, Haifa has become another important Chinese port city in MENA. Bayport terminal, a US$1.7 billion project, opened in September 2021 and is operated by Shanghai International Port Group (SIPG) with a 25-year agreement. The new port allows Haifa to dock larger classes of cargo ships, important for a country that relies on overseas shipping to move approximately 99 per cent of its imports and exports.[35] This capacity is important for Israel because previously its ports could only handle smaller ships and the country frequently experienced seaport traffic jams that resulted in delays costing the Israeli economy approximately US$218 million every month.[36]

For China, having another access point on the Mediterranean coast supports its trade with the European Union. The connecting infrastructure that Israel is planning, including the Red-Med railway and the “Tracks for Regional Peace” rail line that would connect Haifa to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries via Jordan, will also benefit China’s BRI ambitions of cross-regional connectivity.[37]

Haifa has an especially significant impact on the regional strategic landscape, however, and is another example of a pressure point between the United States and an important regional ally. Haifa regularly hosts joint drills between the US and Israeli navies, and the US Navy’s Sixth Fleet frequently docks there. As the Bayport project came closer to completion, the Trump administration lobbied the Israeli government to stop SIPG from managing the port, with rumours at one point that the Sixth Fleet might stop using Haifa as a port of call,[38] and then later requesting that the US Coast Guard be allowed to inspect the port for Chinese surveillance capabilities — a request that was denied by the Israeli government.[39] The Biden administration has continued to voice concerns about Chinese penetration of the Israeli economy, especially in the technology sector and in critical infrastructure. A report from Tel Aviv University’s Institute of National Security Studies acknowledged the challenges Bayport presents: “Under the reasonable assumption that the direct risks potentially arising from Bayport’s operation can be handled prudently and responsibly by Israel’s security authorities, the most significant challenge still remains, namely, the implications for relations with the United States.”[40]

Conclusion

All told, China has been developing a deep commercial presence in ports and industrial parks that link the Persian Gulf to the Arabian, Red and Mediterranean Seas. These projects underscore the importance of the Arabian peninsula and Red Sea for the BRI. Approximately 90 per cent of global trade moves by sea, and the value of maritime trade is projected to triple by 2050.[41] These ports and parks represent the essence of the BRI’s cross-regional connectivity. With the exception of the PLAN’s support base in Djibouti, none of these has any military application yet. However, each of the six countries included here has dense security cooperation agreements with the United States, and the state of the US-China relationship is a factor to consider. During the Trump administration the United States shifted its foreign policy focus from counterterrorism to great power competition, describing China and Russia as the primary threats. This new focus has continued during the Biden administration, although it uses the designation of strategic competition. As a result, Washington has applied considerable pressure on allies and partners to reconsider engagement with China in areas it deems sensitive, such as cooperating with Huawei on 5G telecommunication technology or allowing Chinese companies to manage critical infrastructure. As described above, such pressure has already added to tension in the US-UAE relationship. Similar dynamics are at play in Israel and Saudi Arabia.

Notwithstanding Washington’s suspicions of Beijing’s agenda, the latter, in working closely with US allies and partners in MENA, is not seeking to undermine the US presence and influence in the region. On the contrary, China’s economic interests prize stability, and its approach to the Middle East in fact supports rather than challenges the existing regional order.

* Dr Jonathan Fulton is a political scientist at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, and a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. His latest book is the Routledge Handbook of China– Middle East Relations (Routledge, 2022).

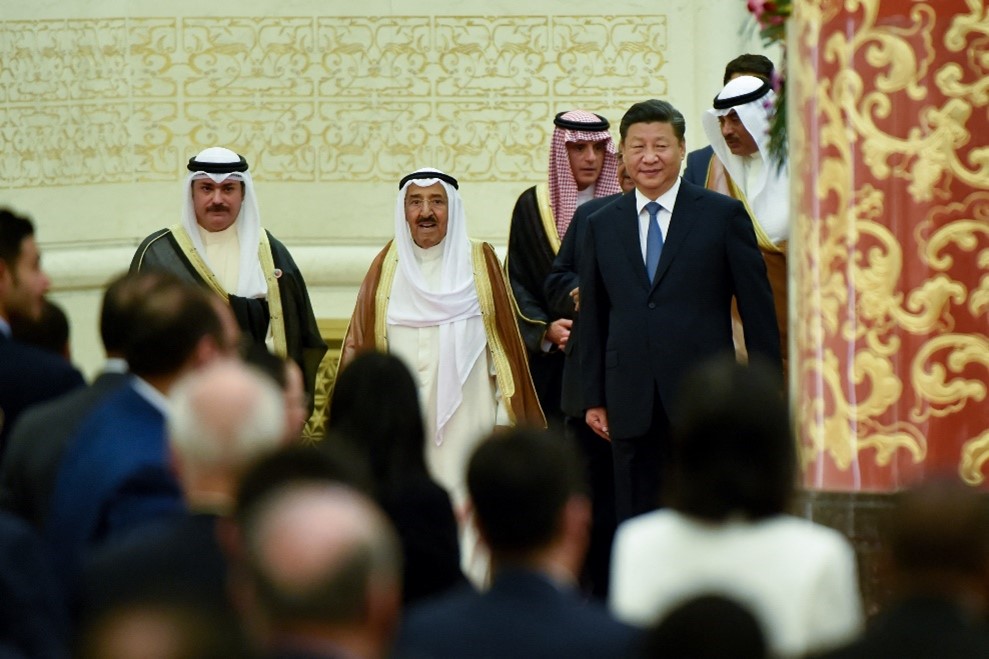

Image caption: China’s president Xi Jinping (R) and Kuwaiti’s emir Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah (C) arrive at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People for the 8th ministerial meeting of the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum on 10 July 2018. The forum launched the “Industrial Park–Port Interconnection, Two-Wheels Two-Wings Approach” framework for the Arab countries to participate in China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative. Photo: Wang Zhao/AFP.

End Notes

[1] For studies on the BRI, see Nadège Rolland, China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative (The National Bureau of Asian Research, 2017); Jonathan Fulton, ed., Regions in the Belt and Road Initiative (Routledge, 2020).

[2] On the MSRI in MENA, see Jean-Marc F. Blanchard, ed., China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative, Africa, and the Middle East: Feats, Freezes, and Failures (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021). For MSRI in the Gulf region, see Jonathan Fulton, “Domestic Politics as Fuel for China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative: The Case of the Gulf Monarchies”, Journal of Contemporary China 29, No. 122 (2020): 175–190.

[3] Degang Sun and Yahia H. Zoubir, “China’s Economic Diplomacy towards the Arab Countries: Challenges Ahead?” Journal of Contemporary China 24, No. 95 (2015): 908.

[4] “Xi says Belt and Road Initiative not geopolitical tool”, Xinhua, 3 September 2017.

[5] Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the United Nations, “Wang Yi: China and Arab states should jointly forge the cooperation layout featuring ‘Industrial Park-Port Interconnection, Two-Wheel and Two-Wing approach’”, 10 July 2018, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/ce/como//eng/news/t1576567.htm

[6] Xue Gong, “China’s Belt and Road Initiative Financing in Southeast Asia”, Southeast Asian Affairs, 2020, 77–95.

[7] Daniel R. Russel and Blake H. Berger, “Weaponizing the Belt and Road Initiative”, Asia Society Policy Institute, 2020, 20.

[8] On the development of the bilateral relationship, see Jonathan Fulton, “China–United Arab Emirates Relations in the Belt and Road Era”, Journal of Arabian Studies 9, No. 2 (2019): 253–268.

[9] On China’s Dubai presence, see Yuting Wang, “Making Chinese Spaces in Dubai: A Spatial Consideration of Chinese Transnational Communities in the Arab Gulf States”, Journal of Arabian Studies 9, No. 2), (2019): 269–287; Yuting Wang, Chinese in Dubai: Money, Pride, and Soul-Searching (Brill, 2020).

[10] “Sheikh Mohammed announces $3.4bn investment in Dubai via China’s Belt and Road Initiative”, The National, 26 April 2019, https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/government/sheikh-mohammed-announces-3-4bn-investment-in-dubai-via-china-s-belt-and-road-initiative-1.854063

[11] Anthony McAuley, “China’s Cosco to build and operate new container terminal at Khalifa Port”, The National, 28 September 2016, https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/chinas-cosco-to-build-and-operate-new-container-terminal-at-khalifa-port-1.201120

[12] “Chinese companies to invest $1bn in Khalifa Port free trade zone”, Emirates 24/7, 20 April 2018, https://www.emirates247.com/business/chinese-companies-to-invest-1bn-in-khalifa-port-free-trade-zone-2018-04-20-1.668346

[13] Warren P. Strobel and Nancy A. Youssef, “F-35 sale to U.A.E. imperiled over US concerns about ties to China”, The Wall Street Journal, 25 May 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/f-35-sale-to-u-a-e-imperiled-over-u-s-concerns-about-ties-to-china-11621949050

[14] Joel Gehrke, “US warns Middle East Allies not to give china a military base”, The Washington Examiner, 10 August 2021, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/policy/defense/national-security/us-warns-middle-east-china-base

[15] Strobel and Youssef, “F-35 Sale to U.A.E. Imperiled”.

[16] Gordon Lubold and Warren P. Strobel, “Secret Chinese port project in Persian Gulf rattles US relations with UAE”, The Wall Street Journal, 19 November 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/us-china-uae-military-11637274224

[17] Mostafa Salem, Jennifer Hansler, and Celine Alkhaldi, “UAE suspends multi-billion dollar weapons deal in sign of growing frustration with US-China showdown”, CNN, 15 December 2021, https://edition.cnn.com/2021/12/14/middleeast/uae-weapons-deal-washington-china-intl/index.html

[18] Mostafa Salem, Jennifer Hansler, and Celine Alkhaldi, “UAE suspends multi-billion dollar weapons”.

[19] Agnes Helou, “UAE to buy a dozen Chinese L-15 trainer aircraft”, DefenseNews, 25 February 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/air/2022/02/25/uae-to-buy-a-dozen-chinese-l-15-trainer-aircraft/.

[20] Eric Staples, “The Ports of Oman Today”, in The Ports of Oman, ed. Abdulrahman Al Salimi and Eric Staples (Georg Olms Verlag, 2017), 362.

[21] Fulton, “Domestic Politics as Fuel for China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative”, 186–7.

[22] Nawied Jabarkhyl, “Oman counts on Chinese billions to build desert boomtown”, Reuters, 5 September 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-oman-china-investment-idUSKCN1BG1WJ

[23] “First factory to open at China-Oman Industrial City in Duqm”, Times of Oman, 23 October 2021, https://timesofoman.com/article/108381-first-factory-to-open-at-china-oman-industrial-city-in-duqm

[24] Derek Scissors, “China’s global business footprint shrinks”, American Enterprise Institute, 10 July 2019, https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/chinas-global-business-footprint-shrinks/

[25] Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook: Oman. (Continuously updated.)

[26] “Oman signs $3.55 Billion loan with Chinese banks”, Reuters, 3 August 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/oman-loan-idUSL5N1KP2XX

[27] Daniel J. Kostecka, “Places and Bases: The Chinese Navy’s Emerging Support Network in the Indian Ocean”. Naval War College Review 64, No. 1 (2011), 65.

[28] Jonathan Fulton, “Situating Saudi Arabia in China’s Belt and Road Initiative”, Asian Politics & Policy 12, No. 3 (2020): 362–383.

[29] Zhishi Yang, Le Du and Liping Ding, “The China-Saudi Arabia (Jizan) Industrial Park under the Belt and Road Initiative”, Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies 14, No. 4 (2020), 534.

[30] Li Wenfang, “Pan-Asia’s Saudi project to break ground next March”, China Daily, 27 June 2017, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2017-06/27/content_29896950.htm

[31] On China’s presence in Djibouti, see David Styan, “China’s Maritime Silk Road and Small States: Lessons from the Case of Djibouti”, Journal of Contemporary China 29, No. 122 (2020): 191–206; Benjamin Barton, “Agency and Autonomy in the Maritime Silk Road Initiative: An Examination of Djibouti’s Doraleh Container Terminal Disputes”, The Chinese Journal of International Politics 14, No. 3 (2021): 353–380.

[32] State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “China’s Military Strategy”, 27 May 2015, http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2015/05/27/content_281475115610833.htm

[33] John Calabrese, “Towering ambitions: Egypt and China building for the future”, Middle East Institute (Washington, DC), 6 October 2020, https://www.mei.edu/publications/towering-ambitions-egypt-and-china-building-future

[34] American Enterprise Institute, China Global Investment Tracker (Continuously updated.)

[35] “Israel opens Chinese-operated port in Haifa to boost regional trade links”, Reuters, 2 September 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/israel-opens-chinese-operated-port-haifa-boost-regional-trade-links-2021-09-02/

[36] Ricky Ben-David, “Israel inaugurates Chinese-run Haifa Port terminal, in likely boost for economy”, The Times of Israel, 2 September 2021, https://www.timesofisrael.com/israel-inaugurates-new-haifa-port-terminal-in-expected-boost-for-economy/

[37] “Israel to begin promoting railway linking Haifa seaport with Saudi Arabia”, The Times of Israel, 24 June 2018, https://www.timesofisrael.com/israel-to-begin-promoting-railway-linking-haifa-seaport-with-saudi-arabia/

[38] Michael Wilner, “US navy may stop docking in Haifa after Chinese take over port”, Jerusalem Post, 15 December 2018, https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/us-navy-may-stop-docking-in-haifa-after-chinese-take-over-port-574414

[39] “Report: Israel turned down US request to inspect Haifa Port after deal with China”, Al Monitor, 1 February 2021, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2021/02/israel-china-haifa-port-inspection.html

[40] Galia Lavi and Assaf Orion, “The Launch of the Haifa Bayport Terminal: Economic and Security Considerations”, The Institute for National Security Studies, 12 September 2021, https://www.inss.org.il/publication/haifa-new-port/.

[41] Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Ocean Shipping and Shipbuilding (Continuously updated.)