By Leonardo Jacopo Maria Mazzucco

The imperative of de-escalation has been entwined in the foreign policy of Middle Eastern countries since mid-2019, when drone attacks claimed by Houthis hit Saudi oil facilities in Abqaiq and Khurais went unanswered by the United States, dismaying Washington’s partners in the Gulf. After almost a decade of conflict that has brought Syria, Libya, Yemen, and Iraq to the brink of collapse, the current balance of power makes it difficult to distinguish between winners and losers. Hawkish confrontations and protracted military engagements have ultimately left countries with depleted financial resources and limited strategic gains. Although the decade-long struggle for influence has dramatically eroded opportunities for regional cooperation, the diminishing returns of assertive foreign policies persuaded Middle Eastern countries, to a greater or lesser extent, to repair ties with their rivals and overcome the trust deficit keeping them apart.

The US’ recalibration of its relationship with the Middle East is a partial explanation for the current regional “thirst for détente”. Despite significant differences in communication style, strategic priorities, and political agenda, it is possible to identify a common pattern in the US approach to the region by the three American presidents. The US’ gradual disengagement from regional affairs is a fil rouge through the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations. While each president signalled Washington’s intention to rationalise the American military presence in the Middle East differently, the message is unmistakeable: Asia is the United States’ current centre of attention. The perception that the US has turned its back on its security assurances to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) has resulted in recurrent misunderstandings, a general worsening of bilateral relations, and a renewed push among Gulf states to cool tensions with adversaries.

Another factor is the Covid-19 pandemic, which accelerated the process of regional repositioning. The mounting financial and human costs associated with the health crisis forced countries to adopt an inward-looking posture, tone down frictions, and implement conservative financial measures. The imperative to rationalise already scarce resources cooled ideology-driven confrontations and made room for new approaches, based on pragmatism and flexibility, to emerge in the regional geopolitical game. But with the Iran nuclear negotiations stalled,[1] and talks between Riyadh and Tehran going nowhere,[2] and the GCC adjusting to a post-Al Ula architecture,[3] the efforts at détente have been halting. The drone and missile attacks by the Houthis against the United Arab Emirates (UAE) for three weeks in a row in January are examples of the emerging threats that the country has to face. Traditionally considered a quiet oasis where luxury tourism and business ventures thrive, the UAE has discovered that it is not as immune as it thought from an otherwise chaos-dominated and conflict-prone region.[4]

But although the attacks raised alarm in Abu Dhabi, they have not diverted the UAE’s attention from its primary strategic goals: Pivoting the Middle East away from a decade of tensions and assuming a leadership role in the regional security order emerging after the Covid-19 pandemic. Through a pragmatism-oriented and economy-driven foreign policy, the UAE’s efforts at normalising ties with its regional competitors – Iran and Turkey – are part of a broader vision to ensure the long-term sustainability of the country’s two main strategic priorities – safeguarding national security and fostering economic prosperity, respectively.

From Rocky to Amicable Relations: The Shifting Tones of Regional Co-Existence

The UAE-Iran and UAE-Turkey relationships have historically gone through several ups and downs. Incendiary rhetoric and antagonist behaviour have inflamed tensions over the last decade, bringing bilateral ties almost to the point of collapse. However, despite the recent period of turbulence, the three countries have adopted milder discursive practices and signalled a political willingness to mend fences.

1.1 BRIDGING THE GULF: THE UAE-IRAN DÉTENTE

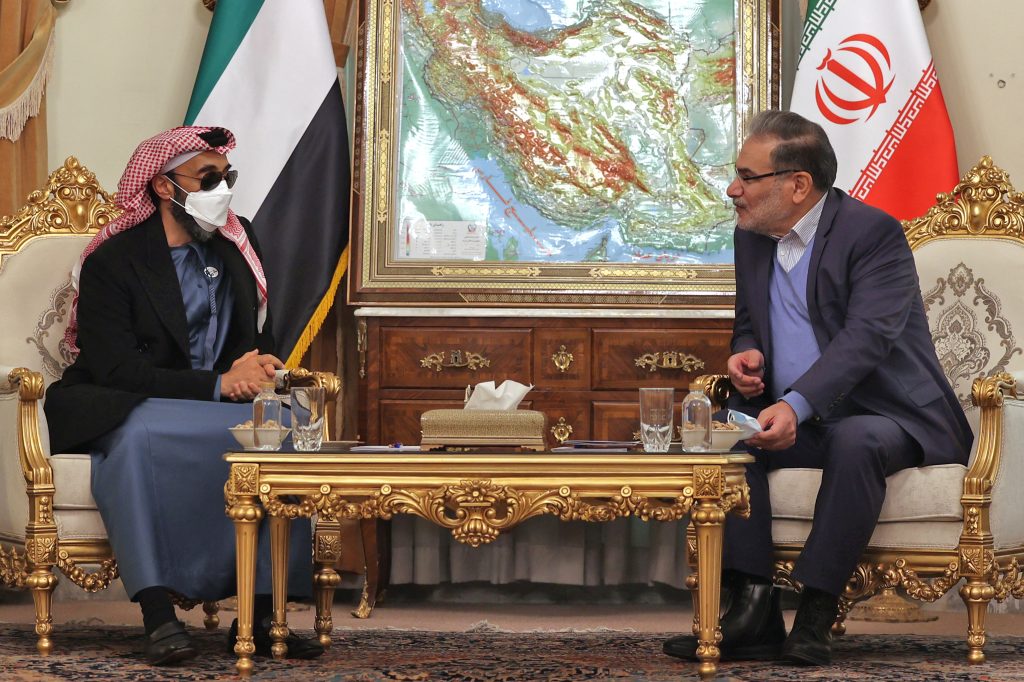

A series of unexpected official visits by high-profile diplomats in late 2021 represented a tentative, genuine effort to resume and consolidate political dialogues between the UAE and Iran. First, Dr Anwar Gargash, a senior diplomatic adviser to the UAE President, and Khalifa Shaheen Al Marar, Emirati Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, met Ali Bagheri Kani, the Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister for Political Affairs, in Dubai to discuss ways to improve bilateral ties.[5] Later, Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the UAE’s National Security Adviser and brother of Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, flew to Tehran, where he sat down with Ali Shamkhani, the head of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, and Iranian President Ibrahim Raisi to explore solutions to regional issues of mutual concern.[6]

Despite this bout of business and shuttle diplomacy, Iran continues to figure prominently in the UAE’s threat analysis.[7] Abu Dhabi’s fear of a nuclear-armed Iran, on the one hand, and Tehran’s continued malign activities in the region, have forced analysts to be cautious about any perceived improvement in bilateral ties.

The recent drone and missile attacks have raised questions about Iranian involvement, at least at the planning and operational levels, and are among the incidents that have cast a shadow over the diplomatic efforts. While there is no convincing evidence yet that Iran gave the Houthis the “green light” for the attacks,[8] the political alignment between them has worsened Iran’s international reputation. It is still unclear whether Iran was sitting in the driver’s or passenger’s seat during the attacks, or if it was kept entirely in the dark by its Yemeni proxy. However, since Iranian-made Zulfiqar ballistic missiles were used,[9] and Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) shipments[10] routinely refill Houthi stockpiles of drones, missiles, and military hardware, Tehran might be considered morally responsible for the attacks.[11]

Though the UAE has sought to mend diplomatic ties with Iran to reduce the risk of re-escalation,[12] Tehran’s unwillingness – or inability – to hold back the Houthis is likely to prevent any further progress in this area. On their end, the Houthis – who do not see themselves as an Iranian proxy – are likely to make things hard for Tehran.[13] Iran is thus caught in the middle of a tricky balancing act between the Houthis and the Emiratis,[14] and will have to consider its next moves carefully. However, with hardlines holding power in Tehran and IRGC officials continuing to make provocative claims against the Gulf monarchies, there is scepticism over whether Iran has a genuine interest in détente. A crucial clue will be whether President Raisi will take up the Emirates’ invite to visit – an invitation issued just two days before the Houthis’ first barrage.[15]

1.2 LET BYGONES BE BYGONES: THE UAE-TURKEY RAPPROCHEMENT

The two-day visit by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to the UAE in February was the last stage of a three-step reconciliation process carefully shaped and guided by Emirati and Turkish diplomatic officials, a process that began at the start of 2021. The official visit of Sheikh Tahnoun bin Zayed Al Nahyan to Turkey in mid-August 2021 was the first high-profile event to publicly signal both sides’ intention to turn the page on the rough patch in bilateral ties after almost a decade of harsh confrontation.[16] The thaw in relations reached its zenith when Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan made a state visit to Turkey on 24 November 2021. Celebrated as the beginning of a “new era”[17], the meeting allowed the two countries to reset their relationship.[18]

On 14 February 2022, President Erdogan reciprocated and was feted at the Qasr Al Watan (Nation’s Palace) in Abu Dhabi. The red-carpet treatment given to the Turkish delegation – including a 21-gun salute, an aerial show featuring the Turkish flag over Abu Dhabi’s Corniche, and a cavalry parade – reflected the political magnitude of the event. After the lavish welcome, Turkish and Emiratis ministers signed 13 Memorandums of Understanding and exchanged warm handshakes.[19]

Economic cooperation is unquestionably behind the rapprochement, and both countries are focused on boosting commercial ties and exploring investment opportunities. The UAE and Turkey agreed on a nearly US$5 billion swap deal to shore up the slumping Turkish lira,[20] and signed a joint statement to start negotiations for a bilateral trade and investment deal, known as a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (Cepa).[21] Abu Dhabi also set up a US$10 billion fund to support an intense investment campaign in the Turkish market, focusing primarily on the trade, transport, health, hospitality, and energy sectors.[22]

These efforts have shown Turkey that the UAE continues to wield considerable economic clout despite the moribund global economy. With its own economy trapped in a dangerous downward spiral and the lira hitting a historic low, a cash-strapped Ankara and an opportunity-seeking Abu Dhabi are natural partners. President Erdogan’s visit to the UAE closed the first circle of the institutional rapprochement between the two countries and paved the way forward. By building on the momentum, Abu Dhabi and Ankara are now in position to scale up bilateral ties, pursue a real détente, and unlock the potential of this newfound convergence of interests.

Mapping Threat Perception Between the UAE, Iran, and Turkey

2.1 NEITHER FRIENDS NOR FOES: RETRACING THE UAE-IRAN RELATIONSHIP

Historically, the UAE and Iran have experienced a tumultuous track record of diplomatic ties, with moments of cordial coexistence alternating with phases of almost open confrontation. From ideological differences to conflicting geopolitical ambitions, and territorial disputes, they seem to sit on a powder keg ready to explode. However, the geographical proximity and converging interests in keeping tensions low in the Strait of Hormuz have pragmatically persuaded them to minimise frictions and maintain an open communications channel.

The UAE and Iran have had a roller-coaster relationship since the early 1970s. Bilateral ties between the two countries did not get off on the right foot as Tehran seized control of three Emirati islands: Abu Musa and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs.[23] But although tensions have waxed and waned,[24] the sabre-rattling between both sides has never spiralled out of control.

Undoubtedly, the seizure of the islands has been seared into the UAE’s institutional memory. The Emirati leadership, especially in Abu Dhabi, has considered Iran the primary threat to its territorial integrity and political sovereignty. Deep concerns over Tehran’s hegemonic attitude prompted the UAE to read Iran’s political moves in the Gulf through a prism of suspicion and mistrust.[25]

Tensions were renewed in 1979, after the Iranian revolution. With the Shia clergy assuming a prominent role in Iranian domestic politics, the ideological cleavage worsened the bad blood running between the two countries. Though the chances of having a homegrown Shia-based political group develop in the UAE are almost negligible, the Emirati leadership has never underestimated the risks associated with Iran’s call to export the revolution.[26] The possibility of Iranians meddling in the UAE’s domestic politics and fomenting subversion was perceived as a real threat to the regime’s integrity and a great danger, especially for those Emirates – such as Dubai – that for commercial, historical, and cultural reasons, were more exposed to Tehran’s influence.[27]

The UAE-Iran relationship entered a dangerous downward spiral when the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was inked.[28] Though the UAE aligned officially with Washington’s posture and genuine hope that the Gulf was on the cusp of a new era[29], Abu Dhabi continued to have major security concerns. With the Emiratis primary security concerns – Iran’s ballistic missile programme and support for regional proxies unaddressed by the JCPOA, the UAE leadership was left cold by the pact. It was a reaction common in the Gulf: The monarchies’ perception was that the US traded their security for an agreement that placed no constraints on Iran’s regional ambitions and thus emboldened it.

The tide appeared to change when the Trump administration took office in the White House. Persuaded that an agreement more favourable to US interests was within reach, President Donald Trump withdrew from the JCPOA and embarked on a “maximum pressure”[30] campaign, which aimed to force Tehran to renegotiate the nuclear agreement through the imposition of harsh economic sanctions.

Though it aligned with President Trump’s assertive posture,[31] the UAE carefully threaded its diplomatic posture to avoid the risk of getting burned by the incendiary rhetoric reigniting the flames of war in the Gulf: While it was interested in capping Iran’s regional ambitions, it saw no gains from letting tensions spark a broader confrontation. This sparked a push to mend fences,

After reaching a nadir with the bombings of some Emirati oil tankers off the coast of Fujairah in May 2019, which were allegedly carried out by Iran, the UAE has since sought to improve relations with Tehran.[32] A series of meetings on maritime security in the Hormuz Strait and fishing issues allowed the Iranian and Emirati coast guards to explore conflict-resolution mechanisms for maritime disputes.[33] Aside from the “routine and technical”[34] aspects, the discussion offered Emirati and Iranian officials an opportunity to lay the foundation for broader de-escalation talks. As a result, the relationship between the two neighbours shifted towards a phase of gradual rapprochement.[35]

As Hussein Ibish pointed out, “the UAE sought policy change, not regime change, in Tehran.”[36] To underscore the point, the UAE’s conciliatory approach during two critical stress tests for the Iranian leadership signalled that pragmatism informed Abu Dhabi’s outreach to Tehran. When IRGC (Major-General Qassem Soleimani was killed in a US strike, Dr Anwar Gargash condemned the assassination[37] and called both parties to abide by “wisdom and moderation”[38] rather than “confrontation and escalation.”[39] When Iran was hit hard by Covid-19, the UAE was among the first countries to send humanitarian aid. In the first two weeks of March 2020, UAE aircraft landed in Iran with over 39 tons of medical supplies and equipment to treat infected patients.[40] A fourth aid plane laden with a new 16-ton batch of urgent medical supplies followed in June 2020.[41]

While security concerns have fuelled the dialogue, the thaw in UAE-Iran tensions has also been driven by economic engagement. According to Bourse & Bazaar Foundation, the UAE has become a major re-export hub for Iranian oil headed for Asian markets, particularly China, since mid-2019. To circumvent US secondary sanctions, oil was transferred from Iranian oil tankers to Emirati ones and rebranded as originating from the UAE. Iran’s trade deficit with the UAE – expected to reach US$8 billion in the 2021 fiscal year – and Chinese import data which shows Emirati oil exceeding the country’s production projections provide evidence of this scheme.[42] The UAE is perfectly suited to tasks like these – it has cutting-edge logistic facilities, a thriving financial sector, and is a commercial entrepôt embedded in the global trade networks. Abu Dhabi thus provided a lifeline for an Iran being choked by crippling sanctions.

Thus, despite the occasional sabre-rattling, geographical proximity, a mutual determination to limit Saudi hegemonic ambitions in the Gulf, and a converging interest in keeping tensions low around the Hormuz Strait have persuaded the UAE and Iran to minimise frictions and maintain an open channel of communication.

2.2 A BITTERSWEET STORY: RETRACING THE UAE-TURKEY RELATIONS

While the Ottoman imperial legacy has often prompted the Gulf monarchies to look at Turkey grimly, ties between Ankara and Abu Dhabi were generally amicable between the 1980s and early 2010s.

Turkey has generally been a risk-averse player for most of its modern history, and Ankara’s foreign policy has been shaped to serve domestic goals, particularly securing its political system against internal and external threats.[43] The catalyst for closer ties in the early 1980s was the emergence of a common threat perception at the domestic level: A spillover of revolutionary-oriented political Islam from Iran to the region.[44]

This alignment of interests opened up booming two-way trade between the Gulf and Turkey – goods from the latter flooded GCC markets , while the petro-rich states reciprocated by financing entrepreneurial activities in the former.[45] Turkey’s decision to join the international coalition against the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait also helped: The Gulf monarchies saw this as an act of a responsible neighbour.[46] The convergence between the UAE and Turkey was also on display when the US-led coalition invaded Iraq in March 2003. Both Mr Erdogan, who was then PM, and then-UAE President Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan condemned the move. They realised that a power vacuum in Iraq would embolden Tehran, an assessment that turned out to be accurate.[47] Ultimately, Turkey-GCC relations reached their peak in September 2008, when Ankara was endowed with the title of strategic partner, and a High-Level Strategic Dialogue was launched.[48]

However, this carefully-built relationship was soon tested as the Arab uprisings shook the Middle Eastern status quo dramatically. As differences in threat perception intensified and power vacuums emerged in historical regional powerhouses, relations between Turkey and the UAE grew apart: While Turkey championed an almost revolutionary political approach solidly anchored on a religious-conservative core, the UAE pushed a pro-status quo political vision based on a moderate understanding of Islam. Fearing a domino effect spreading political instability and regime change all over the Middle East, the UAE and Turkey initially looked at the Arab street protests through a security lens. However, the unprecedented opportunity to redraw the region’s political geography to a setting more in tune with their strategic priorities – namely, promoting a politically conservative balance of power for the UAE and supporting a revisionist political agenda for Turkey – persuaded them to abandon the early timid approach for a more assertive posture.[49]

The reshuffling of the regional balance of power and the emergence of a more permissive strategic environment persuaded the AKP élite that it was the right moment for Turkey to emerge as a global champion and position itself as the natural leader of a major regional political transformation underpinned by Islamic and democratic principles. Then-PM Erdogan’s inner circle believed that the country’s strategic interests would have been better served by a radical shift in the tenets orienting Turkish foreign policy and the tools supporting its strategy abroad. As a result, by abandoning the “zero problems with neighbours”[50] foreign policy, designed by the former Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu and aimed at establishing a network of friendly relationships between the country and its broader neighbourhood, Turkey pursued more assertive power projection in the Middle East.[51]

Imbued with neo-Ottoman rhetoric, Turkish political ambitions led it to seek leadership in both the political and religious domains, setting it on a collision course with both Saudi Arabia, the self-described guardian of Islam, and the UAE, the torch-bearer of a moderate approach to religion.[52] Turkey identified Muslim Brotherhood-style Islamist groups as viable allies to redefine the regional order, but the UAE considered them terrorist formations menacing its domestic security. Consequently, as social tensions wrought havoc in different conflict theatres across the Middle East, bilateral ties got progressively sour. [53]

The ideological fracture worsened when General Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi ousted Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi in July 2013. Elected under the banner of the Freedom and Justice Party, an AKP-inspired and Muslim Brotherhood-based Egyptian political party, President Morsi found in Mr Erdogan a trusted partner and a political reference point.[54] Sympathetic towards the Muslim Brotherhood’s cause,[55] the AKP-led government offered a safe harbour to thousands of MB affiliates and supporters escaping the Egyptian clampdown.[56] Fraying ties were made worse by the failed 2016 coup attempt in Turkey.[57] While President Erdogan and pro-government media platforms immediately accused Fethullah Gülen as the mastermind behind the attempted putsch,[58] some Turkish media outlets nurtured the narrative that the coup plotters were financially backed by the UAE.[59]

Bilateral relations between Ankara and Abu Dhabi continued to worsen during the 2017 Gulf crisis. With intra-GCC ties at their lowest and hostilities simmering since the outbreak of the Arab uprisings, tensions boiled to breaking point when the Quartet – a bloc comprising Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the UAE, and Egypt – imposed an air, land, and sea boycott on Qatar. The Turkish offer of unconditional support to Qatar and the rapid deployment of 5,000 Turkish troops to the Tariq bin Ziyad military base in southern Doha rang alarm bells in Abu Dhabi.[60] With Ankara securing a military foothold in the Gulf, the Emirati perception of Turkey dramatically deteriorated. Once considered a partner and a counterweight to Iran, Turkey ended up being not only “a new rival”[61] for political leadership in the Middle East, but also a security threat to Gulf stability. Given Ankara’s ideological affinity with Muslim Brotherhood-style Islamist groups around the region, it is no surprise that Abu Dhabi was deeply concerned about seeing in its backyard a country well-known for having close ties with what the UAE considered terrorist groups and an existential threat to its national security.

Engulfed in an increasingly tense quest for regional leadership, the UAE-Turkey rivalry rapidly spilled over into new theatres of confrontation, such as the Eastern Mediterranean and Libya. Over the last few years, the UAE has developed close diplomatic and commercial ties with Greece and Cyprus, Ankara’s historical nemesis. The UAE has participated in several military drills in the Eastern Mediterranean since 2017,[62] and DP World, Dubai’s logistics powerhouse, gained a foothold in the Mediterranean by inaugurating a cruise passenger terminal at the Cypriot Limassol port in 2018.[63] Although the Palestinians vetoed the UAE’s membership in the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF),[64] an eight-member platform for policy coordination on natural gas, Abu Dhabi has come to play a critical role in the region’s gas game since December 2020.[65]

Libya was another flashpoint. While Ankara supported the United Nations-recognised government in Tripoli led by Fayez al-Sarraj, Abu Dhabi backed Field-Marshal Khalifa Haftar, leader of the Cyrenaica and primary sponsor of the Tobruk-based government. After the harsh escalation of Haftar’s siege on Tripoli in April 2019, Turkish military support to al-Sarraj was critical in preventing the government from collapsing.[66] Since then, the armed confrontation has reached a standoff, and parties have consolidated power in their respective influence spheres, divided along the Sirte “red line”.[67] As the UAE extended its power projection capacity to the Mediterranean and closed ranks with Turkey’s historical rivals, it is no surprise that Abu Dhabi’s encroachment in an area traditionally considered by Turkey as its natural sphere of influence nurtured anxiety and fear of encirclement.

Stabilising the Regional Order

3.1 UAE

While Iran’s hawkish posture in the region has undoubtedly been a driver for UAE-Israel cooperation in the security and defence domains,[68] Abu Dhabi is not deaf to the security concerns emerging from its surrounding neighbourhood. As tension between Iran and Israel worsens in the wake of the Iranian ballistic missile attack on an alleged Mossad base in Erbil – in retaliation for the Israeli assassination of two IRGC generals in Syria and the sabotage of a drone factory in western Iran[69] – the UAE has a golden opportunity to prevent low-intensity skirmishes from spinning out of control. Indeed, as proposed by Danny Citrinowicz, the time might be right for the UAE “to use the Abraham Accords not only as a stick to threaten Iran, but as a means of defusing tension in the region”.[70] By understanding the threat perceptions dominating Israeli and Iranian security environments and having a vested interest in toning down animosities, the UAE is well-positioned to act as a regional stabilising force.

Besides, with Muslim Brotherhood-inspired networks suffering chronic defeats across the Middle East, political Islam is a less worrisome threat to the UAE than it was in the past. With the ideological factor removed from the geopolitical equation and Ankara cooling down its pan-Sunni narrative, both countries seem to have enough goodwill and incentives to scale up the rapprochement. After a decade of colliding strategies, both countries seem ready to bet on nurturing regional stabilisation and enhancing economic cooperation.

3.2 IRAN

Crippling economic sanctions, tense relations with its regional Arab neighbours, and the impact of Covid-19 have extracted a heavy toll on Iran and condemned its population to living hand-to-mouth to cope with dire socio-economic conditions. Though the “maximum resistance” policy seems to have successfully delivered on its initial promises, it is far from being a challenge- and cost-free approach. Indeed, Iran’s fatigued economy has exposed the regime’s domestic vulnerabilities and nurtured widespread social malaise, with popular protests erupting from time to time, especially in the Khuzestan and Baluchistan regions.[71] With an economy in bad shape and people increasingly defying the government’s calls for patience, President Raisi’s capacity to deflect domestic criticism through the traditional sanctions scapegoat and the country’s “maximum resistance” policy are being seriously questioned.[72] Repairing ties with the other side of the Gulf might help Tehran nudge its rivals toward less hawkish positions regarding the nuclear talks and reduce their opposition to a potential “JCPOA 2.0”, which benefits Iran.

One roadblock is the ascent of hardliners in Tehran. Unlike former President Rouhani, who sought to boost constructive engagement and establish good neighbourly relationships with the GCC states through the Hormuz Peace Endeavor (HOPE),[73] an organic proposal for the creation of new regional security architecture,[74] Mr Raisi’s call for détente with the Arab Gulf states is not yet rooted in a deep moment of policy re-examination in Tehran,”[75] noted Alex Vatanka, the Director of the Iran Program at the Middle East Institute in Washington, D.C. Additionally, the fear remains in both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi that an Iran freed from sanctions will use its new-found largesse to bolster its militias across the Middle East.

In the absence of an institutionalised mechanism to manage tensions and promote de-confliction, Tehran continues to rely on less-conventional tools to telegraph its dissent. In this regard, missile and drone attacks, directly or through its proxies,[76] are used to signal strategic red lines and nudge adversaries into making more concessions is a consolidated trope of Iran’s foreign policy. Tehran made no secret of its willingness to go the extra mile to defend its strategic priorities. Nevertheless, Tehran might have also concluded that the Abraham Accords are a reality it cannot wish away. Entertaining détente with the UAE might thus be a way of dissuading the newly-formed partnership from assuming more hawkish positions, which risks having tensions to spin out of control.

3.3 TURKEY

With the 2023 parliamentary and presidential elections around the corner, President Erdogan may have calculated that prolonged diplomatic isolation and a comatose economy are a recipe for disaster – both for the country and the AKP, which has traditionally anchored its domestic consensus on phases of strong economic growth. Turkey’s desire to repair ties with regional competitors clearly indicates President Erdogan’s drive to stabilise the domestic economy before the elections.

In this regard, Ankara has visibly softened the incendiary narrative used in the past against the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Israel in favour of more conciliatory tones. The thaw in UAE-Turkey ties is not a one-off effort, but reflects broader diplomatic manoeuvring to overcome the isolation of Ankara from its natural neighbourhood. Indeed, during the last year, Turkey has sought to restore amicable relations with Greece,[77] Armenia,[78] and, most importantly, Israel. The state visit of Israeli President Isaac Herzog to Ankara on 9 March made the beginning of a new phase in the Turkey-Israel bilateral ties official.[79] Common security, economic, and energy concerns have emerged as the main drivers underpinning the rapprochement between Turkey and Israel.[80] While political normalisation is slowly gaining traction at the institutional level, intelligence cooperation between both countries does not seem to have ever stopped, especially when it comes to checking Iranian-backed Shite militia groups operating in Syria and Northern Iraq. The joint covert operation that thwarted the assassination attempt of Yair Geller, a Turkish-Israeli defence sector tycoon, by an Iranian espionage network based in Ankara is a case in point.[81]

Given Turkey’s constant thirst for energy and Israel’s mounting ambition to earn big from its gas fields, energy talks are likely to accelerate the rapprochement. Washington’s decision to pull the plug from the East Med Pipeline project,[82] a challenging initiative thought to connect the Eastern Mediterranean’s gas basin to continental Europe and bypass Turkey, could be a blessing in disguise for Turkey-Israel ties. With political relations moving on, Turkish and Israeli business circles appear ready to reap the benefits of the rapprochement, as signalled by the MoU signed in Tel Aviv by the Turkish and Israeli trade missions ahead of President Herzog’s visit to Ankara.[83] Building on a solid basis of US$8.4 billion in bilateral trade in 2021,[84] financial and commerce-related opportunities will likely offer a fertile ground for diplomatic talks to scale up.

There is still some caution on the Israeli side, however. Tel Aviv remains suspicious about the motivations driving the Turkish push for rapprochement.[85] Turkey’s massive dependence on Iran for its energy security and its close relationship with Hamas have led to an abundance of caution from Israel.[86]

A New Role for the UAE

The UAE’s détente with Turkey and Iran has been accompanied by a parallel three-step effort by Abu Dhabi to close ranks with its regional partners. Starting with the first of its kind trilateral meeting reuniting the Emirati, Israeli, and Egyptian leaders in Sharm El-Sheikh,[87] continuing with the Aqaba talks gathering the Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed, Jordan’s King Abdullah, Egyptian President al-Sisi, and Iraq’s PM Mustafa al-Kadhimi,[88] and culminating with the Negev Summit bringing together the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco, and Egypt’s foreign ministers as well as US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken,[89] the UAE has shown its interest in shaping multilateral solutions to the regional security dilemmas. Abu Dhabi is signalling to Washington and its regional partners that it has the political goodwill and diplomatic reactivity to act as a unifier capable of rallying together like-minded US Middle Eastern partners in a joint effort for regional stabilisation.

Similarly, the UAE is taking into its own hands the leadership of the diplomatic rapprochement between the Arab world and Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad. It has carefully threaded its outreach to the Assad regime during the last few years by engaging in very active shuttle diplomacy.[90] Starting back in 2019, when an Emirati business delegation attended a trade fair in Damascus,[91] the normalisation effort has seen a significant acceleration during the last six months. With the UAE foreign minister Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed making an official state trip to Damascus in November 2021[92] and President al-Assad reciprocating by visiting the UAE last March – his first overseas appearance since the start of the Syrian civil war[93] – Abu Dhabi has positioned itself at the forefront of Syria’s rehabilitation process. While this triggered some discontent in Washington,[94] Arab countries sharing Abu Dhabi’s regional strategic vision would likely align with the UAE-led political track and seek to bring the Assad regime back to the Arab camp.

Saudi Arabia, which is also seeking a rapprochement with Turkey[95] and Iran[96], is watching the UAE’s moves carefully. Though Saudi and Emirati strategic interests have traditionally converged, some daylight has emerged in the relationship, with spats occasionally erupting on a number of issues, from the Yemeni war[97] to energy policies[98]. By perceiving itself as a legitimate hegemon in the Arabian Peninsula, Saudi Arabia is reluctant to allow the emergence of alternative centres of power. But as long as the benefits associated with the UAE’s “shuttle diplomacy” also strengthen its strategic interests, it is likely to welcome Abu Dhabi’s independent initiative.

Though Saudi Arabia and the UAE have recurrently found a way to manage their rifts peacefully, tensions are likely to come to the surface again if root causes of friction are not carefully tackled. Should animosity intensify, Riyadh might weigh on its material strength to nudge Abu Dhabi to follow its lead. By bidding on its much larger population and a gross domestic production that doubles that of the UAE, Saudi Arabia seems to emerge as the favourite candidate.[99] Due to the size imbalance, the UAE has no interest in engaging in a head-on confrontation with Saudi Arabia. On the contrary, it is likely to hedge its bets on the country’s dynamism and flexibility, which only a progressive business hub perfectly integrated into the global market and the international system, as the UAE, enjoys.

Burdened by material and ideological constraints, the Saudi approach to international affairs is generally based on prudence. However, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s quest for regional and international recognition might persuade Riyadh to take a more proactive role in Middle Eastern politics, Banking on a decade-long legacy of leadership, the House of Al Saud feels it has the political responsibility and the credentials to set the course of Gulf affairs, especially when it comes to Iran. While the Saudi-led call to settle the Dorra gas field’s border dispute with Iran seems to confirm its ambition,[100] it is too early to say if Saudi Arabia’s efforts would be strong enough to persuade the other Gulf monarchies to line up with its lead on big-ticket issues.

The UAE’s Pivot to Southeast Asia

Among the many reasons underpinning the UAE’s outreach to Iran and Turkey is the Emirati desire to rationalise its financial and diplomatic resources and partially redirect them to support its “Look East” policy. As highlighted by Amjad Ahmad, a resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East, “reducing the temperature in the region has a clear economic policy objective of preserving capital and attracting foreign investment.”[101] Though it is still too early to say if the momentum for reconciliation will last, it is clear that the UAE has prioritised its long-term economic ambitions over short-term geostrategic gains.[102]

With the US reaching energy self-sufficiency, European energy demand on the wane – the current crisis in Ukraine notwithstanding – and the lion’s share of global energy demand shifting eastward, it is not by chance that the energy security prism has long dominated the UAE’s perception of the South-east Asian countries. Thriving economies with a constantly rising thirst for energy, Asian markets are the perfect match for UAE-flagged oil tankers. Indeed, Japan, China, India, Thailand, and South Korea are the top 5 destination countries for the UAE’s crude oil exports.[103]

Though the energy file is a critical component of the UAE-Asia ties, it is only one of the variables. The mounting imperative to pivot the UAE economy from a revenue-based to a knowledge-based system and the rising urgency to enhance the country’s commercial attractiveness has prompted the Emirates to look at Asia through new lenses. As a result, non-oil trade opportunities have flourished, primarily in highly-specialised industries, with nuclear energy, healthcare, and advanced technologies topping the list.

Conclusion

With the Arab uprising receding in the rear-view mirror and uncertainty over the future of US security guarantees to the Middle East, the UAE is determined to push for stability in the region. To this end, it has used a diplomacy-first and business-oriented foreign policy to create a string of “pearls” extending from the Aegean Sea to the Malacca Strait.

But despite signs for optimism, the region’s geopolitical map remains too volatile and dotted with flashpoints to determine whether this strategy will succeed. While countries appear to be less inclined to indulge in confrontation, the region suffers from a severe trust deficit, and caution is the order of the day.

Whether the UAE will uphold what seems to be a new “zero problem” policy[104] – based on mending fences with its regional competitors – or stay loyal to its traditional “coercive” policy[105], which is focused on an assertive promotion of the country’s strategic agenda, the following months will be crucial. It is not outside the realm of possibility that the Emirates will settle on a third option: Twinning these policies to suit circumstances, so that it remains flexible enough to deal with the times.

Image Caption: Ali Shamkhani (R), Iran’s Secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, meets with Sheikh Tahnoun bin Zayed al-Nahyan (L), the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) National Security Adviser, in Tehran on 6 December, 2021. Photo: Atta KENARE / AFP

About the Author

Leonardo Jacopo Maria Mazzucco is a researcher in the Strategic Studies Department at TRENDS, Research & Advisory, an independent think-tank in Abu Dhabi. He is also a Research Assistant at Gulf State Analytics (GSA), a Washington-based geopolitical risk consultancy. Mr Mazzucco has an MA degree in Comparative International Relations from Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. He has also completed a second MA degree in Middle Eastern Studies from the Graduate School of Economics and International Relations at the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart in Milan, Italy

End Notes

[1] Ghaida Ghantous, “U’s Borrell says nuclear agreement with Iran ‘very close’,” Reuters, March 26, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/eus-borrell-says-nuclear-agreement-with-iran-very-close-2022-03-26/.

[2] “Iran suspends talks with Saudi, slams Riyadh’s executions,” Reuters, March 13, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iran-suspends-talks-with-saudi-arabia-nour-news-2022-03-13/.

[3] Imad K. Harb, “A New Strategic Architecture Is Emerging in the Gulf,” Arab Center Washington DC, September 24, 2021, https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/a-new-strategic-architecture-is-emerging-in-the-gulf/.

[4] David Rosenberg, “Missile Attacks Shatter UAE’s Reputation as Quiet Oasis in a Turbulent Middle East,” Haaretz, January 30, 2022, https://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/missile-attacks-shatter-uae-s-reputation-as-quiet-oasis-in-a-turbulent-middle-east-1.10571265.

[5] “Gargash, Al Marar meet with Iranian Deputy FM,” Emirati News Agency – WAM, November 25, 2021, https://wam.ae/en/details/1395302996628.

[6] Nasser Karimi And Jon Gambrell, “Top UAE adviser makes rare trip to Iran amid nuclear talks,” The Associated Press (AP), December 6, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-iran-israel-dubai-united-arab-emirates-509050c8e4cf18b02dfda9c9b9bd3f5e.

[7] Peter Salisbury, “Risk Perception and Appetite in UAE Foreign and National Security Policy,” Chatham House, July 2020, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-07-01-risk-in-uae-salisbury.pdf.

[8] Bilal Y. Saab, “How involved was Iran in the Houthi attack on the UAE?,” Middle East Institute, January 20, 2022, https://www.mei.edu/publications/how-involved-was-iran-houthi-attack-uae.

[9] Jon Gambrell, “UAE, US intercept Houthi missile attack targeting Abu Dhabi,” The Associated Press (AP), January 25, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-media-dubai-united-arab-emirates-abu-dhabi-a507ac70e7d4739afd535f0f9477e7fc.

[10] Joseph Haboush, “US Navy intercepts weapons shipment from Iran to Yemen’s Houthis,” Al Arabiya English, December 23, 2021, https://english.alarabiya.net/News/gulf/2021/12/23/US-Navy-intercepts-weapons-shipment-from-Iran-to-Yemen-s-Houthis.

[11] Benoit Faucon and Dion Nissenbaum, “Iran Navy Port Emerges as Key to Alleged Weapons Smuggling to Yemen, U.N. Report Says,” The Wall Street Times, January 9, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/iran-navy-port-emerges-as-key-to-alleged-weapons-smuggling-to-yemen-u-n-report-says-11641651941#:~:text=Deliveries%20of%20weapons%20to%20the,said%20likely%20originated%20in%20Jask.

[12] Dr. Javad Heiran-Nia, “New Horizons: The UAE Recalibrates Its Relations With Iran,” MANARA Magazine, January 21, 2022, https://manaramagazine.org/2022/01/21/new-horizons-the-uae-recalibrates-its-relations-with-iran/.

[13] Gregory D. Johnsen, “Under Pressure, the Houthis May Once Again Turn to Iran,” The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, January 14, 2022, https://agsiw.org/under-pressure-the-houthis-may-once-again-turn-to-iran/.

[14] “Iran attempts difficult balancing act as Houthis target UAE,” Amwaj Media, January 25, 2022, https://amwaj.media/media-monitor/iran-avoids-commenting-on-houthi-strikes-on-uae.

[15] “UAE invites Pres. Raisi for an official visit to Abu Dhabi ,” Iran Press, January 15, 2022, https://iranpress.com/content/53458/uae-invites-pres-raisi-for-official-visit-abu-dhabi.

[16] Suzan Fraser and Aya Batrawy, “Top UAE security chief visits Turkey after years of tension”, The Associated Press, August 19, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/europe-middle-east-business-turkey-059bc288038fd6c46b1c444319f9f683.

[17] “UAE visit to Turkey ‘marks new era’ in relations, says Dr Sultan Al Jaber,” The National, November 24, 2021, https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/government/2021/11/24/uae-visit-to-turkey-marks-new-era-in-relations-says-dr-sultan-al-jaber/.

[18] “Erdogan, MBZ meet for first time in nearly a decade,” Al Monitor, November 24, 2021, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2021/11/erdogan-mbz-meet-first-time-nearly-decade#ixzz7Of68q8bC.

[19] “Turkey’s President Erdogan arrives on first official visit to UAE in nearly a decade,” The National, February 14, 2022, https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/government/2022/02/13/turkeys-president-erdogan-on-first-official-visit-to-uae-in-nearly-a-decade/.

[20] Daren Butler, “Turkey strikes currency swap deal with UAE as ties warm,” Reuters, January 19, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/turkey-strikes-currency-swap-deal-with-uae-ties-warm-2022-01-19/.

[21] “Turkey, UAE sign agreements on trade, industry during Erdogan visit,” Reuters, February 14, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/turkeys-erdogan-visits-uae-first-time-decade-2022-02-14/.

[22] “UAE establishes $10bn fund to support Turkey investments,” The National, November 24, 2021, https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/government/2021/11/24/uae-establishes-10bn-fund-to-support-turkey-investments/.

[23] Kourosh Ahmadi, Islands and International Politics in the Persian Gulf: The Abu Musa and Tunbs in Strategic Context, (Abingdon: Routledge, 2012).

[24] Mahmoud Habboush, “Iran’s Occupation of Gulf Islands ‘Shameful’, Says Minister,” The National, April 21, 2010, https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/iran-s-occupation-of-gulf-islands-shameful-says-minister-1.501529. Thomas Erdbrink, “A Tiny Island is Where Iran Makes a Stand,” The New York Times, April 30, 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/01/world/middleeast/dispute-over-island-of-abu-musa-unites-iran.html.

[25] William A. Rugh, “The Foreign Policy of the United Arab Emirates,” Middle East Journal 50, no.1 (Winter 1996): 57-70, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4328896.

[26] Lawrence Louër, Transnational Shia Politics: Religious and Political Networks in the Gulf (New York:

Columbia University Press, 2008): 156-176.

[27] Karim Sadjadpour, “The Battle of Dubai: The United Arab Emirates and the U.S.-Iran Cold War,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, July 2011, https://carnegieendowment.org/files/dubai_iran.pdf.

[28] F. Brinley Bruton, “Iran Nuclear Deal Highlights: The Good, the Bad, the Complicated,” NBC News, July 14, 2015, https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/iran-nuclear-talks/iran-nuclear-deal-what-it-says-n391656.

[29] “Iran Nuclear Deal Could Turn ‘New Page’ for Gulf: UAE,” Al Arabiya, July 14, 2015, https://english.alarabiya.net/News/middle-east/2015/07/14/Iran-nuclear-deal-could-turn-new-page-for-Gulf-UAE.

[30] Steve Holland and Stephen Kalin, “Trump puts sanctions on Iranian supreme leader, other top officials,” Reuters, June 24, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-iran-usa-idUSKCN1TP13D.

[31] “UAE supports U.S. withdrawal from Iran nuclear deal: state news agency,” Reuters, May 8, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iran-nuclear-emirates-idUSKBN1I92Z1.

[32] Jon Gambrell, “Tankers reported damaged off UAE on major oil trade route,” The Associated Press, May 14, 2019, https://apnews.com/article/north-america-ap-top-news-international-news-sabotage-iran-3884ea5ef0084d7a9e8a7d48c03fb69e.

[33] Rory Jones and Benoit Faucon, “Iran, U.A.E. Discuss Maritime Security Amid Heightened Tensions in Gulf,” The Wall Street Journal, July 30, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/iran-u-a-e-discuss-maritime-security-amid-heightened-tensions-in-gulf-11564505465.

[34] “UAE, Iran coast guards tackle fishing issues,” Khaleeji Times, July 30, 2019, https://www.khaleejtimes.com/region/uae-iran-coast-guards-tackle-fishing-issues–.

[35] Hussein Ibish, “UAE Outreach to Iran Cracks Open the Door to Dialogue,” The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, August 1, 2019, https://agsiw.org/uae-outreach-to-iran-cracks-open-the-door-to-dialogue/.

[36] Hussein Ibish, “UAE Outreach to Iran Cracks Open the Door to Dialogue,” The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, August 1, 2019, https://agsiw.org/uae-outreach-to-iran-cracks-open-the-door-to-dialogue/.

[37] Mohammed Alkhereiji, “Saudi Arabia and UAE call for de-escalation after Soleimani killing,” The Arab Weekly, January 5, 2020, https://thearabweekly.com/saudi-arabia-and-uae-call-de-escalation-after-soleimani-killing.

[38]@AnwarGargash, (2020, Jan 3) في ظل التطورات الإقليمية المتسارعة لا بد من تغليب الحكمة والاتزان وتغليب الحلول السياسية على المواجهة والتصعيد، القضايا التي تواجهها المنطقة معقدة ومتراكمة وتعاني من فقدان الثقة بين الأطراف، والتعامل العقلاني يتطلب مقاربة هادئة وخالية من الإنفعال. [Twitter post]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/AnwarGargash/status/1213035692592422912?s=20&t=31ulaUztV9O0CGIYJ34kdg.

[39] Ibid.

[40] “UAE Sends Aid Flight to Iran to Support Fight Against Corona virus,” United Arab Emirates Ministry of Foreign Affairs & International Cooperation, March 16, 2020, https://www.mofaic.gov.ae/en/mediahub/news/2020/3/16/16-03-2020-uae-iran.

[41] “UAE Sends Additional Aid to Iran in Fight against COVID-19,” United Arab Emirates Ministry of Foreign Affairs & International Cooperation, June 27, 2020, https://www.mofaic.gov.ae/en/mediahub/news/2020/6/27/27-06-2020-uae-iran.

[42] Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, “UAE Earns Big as Iran Sells Oil to China,” Bourse & Bazaar Foundation, October 27, 2021, https://www.bourseandbazaar.com/articles/2021/10/27/uae-earns-big-as-iran-sells-oil-to-china.

[43] Fiona B. Adamson, “Democratization and the Domestic Sources of Foreign Policy: Turkey in the 1974 Cyprus Crisis”, Political Science Quarterly 116, no. 2, (2001): 277-303. https://doi.org/10.2307/798062.

[44] Özden Zeynep Oktav, “The Arab Spring And Its Impact On Turkey-GCC States Partnership”, Siyasal Bilgiler Fakültesi Dergisi (İSMUS), I/1, (2016): 43-69. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2960892.

[45] Suliman Al-Atiqi, “Turkey-GCC Relations: Trends and Outlook”, The Oxford Gulf & Arabian Peninsula Studies Forum (OxGAPS) and The International Cooperation Platform (ICP), 2015. https://www.oxgaps.org/files/turkey-gcc_relations_trends_and_outlook_2015.pdf.

[46] Cameron S. Brown, “Turkey in the Gulf Wars of 1991 and 2003”, Turkish Studies 8, no. 1 (2007): 85–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683840601162054.

[47] Özden Zeynep Oktav, “The Arab Spring And Its Impact On Turkey-GCC States Partnership”, op. cit.: 43-69.

[48] Alaa Al-Din Arafat, “Regional and International Powers in the Gulf Security”: 171-197.

[49] Özden Zeynep Oktav, “The Arab Spring And Its Impact On Turkey-Gcc States Partnership”, op. cit.: 43-69.

[50] Alessia Chiariati and Federico Donelli, “Turkish ‘Zero Problems’ between Failure and Success,” Centre for Policy and Research on Turkey (ResearchTurkey) 4, no. 3 (2015): 108.

[51] Federico Donelli, “Explaining the Role of Intervening Variables in Turkey’s Foreign Policy Behaviour,” Interdisciplinary Political Studies 6, no. 2 (2020): 223-257, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3815489.

[52] Ibid.

[53]Suliman Al-Atiqi, “Turkey-GCC Relations: Trends and Outlook”, op. cit.: 26-21.

[54] Jeffrey Fleishman, “Growing ties between Egypt, Turkey may signal new regional order,” Los Angeles Times, November 13, 2012, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2012-nov-13-la-fg-egypt-turkey-20121113-story.html.

[55] Soner Cagaptay, “Erdogan’s Empathy for Morsi,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, September 14, 2013, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/erdogans-empathy-morsi.

[56] Abdelrahman Ayyash, “The Turkish future of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood,” The Century Foundation, August 17, 2020, https://tcf.org/content/report/turkish-future-egypts-muslim-brotherhood/.

[57] Gönül Tol, Matt Mainzer, and Zeynep Ekmekci, “Unpacking Turkey’s Failed Coup: Causes and Consequences,” Middle East Institute, August 17, 2016, https://www.mei.edu/publications/unpacking-turkeys-failed-coup-causes-and-consequences.

[58] Peter Beaumont, “Fethullah Gülen: who is the man Turkey’s president blames for coup attempt?,” The Guardian, July 16, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jul/16/fethullah-gulen-who-is-the-man-blamed-by-turkeys-president-for-coup-attempt.

[59] Yunus Paksoy, “UAE allegedly funneled $3B to topple Erdoğan, Turkish government,” Daily Sabah, June 13, 2017, https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/2017/06/13/uae-allegedly-funneled-3b-to-topple-erdogan-turkish-government.

[60] Daren Butler and Tulay Karadeniz, “Turkey sends Qatar food and soldiers, discusses Gulf tensions with Saudi”, Reuters, June 22, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-gulf-qatar-turkey-saudi-idUSKBN19D0CX.

[61] Youssef Sheiko, “The United Arab Emirates: Turkey’s New Rival,” Fikra Forum – The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, February 16, 2018, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/united-arab-emirates-turkeys-new-rival.

[62] Gili Cohen, “Israeli Air Force Holds Joint Exercise With United Arab Emirates, U.S. and Italy,” Haaretz, March 29, 2017, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/israeli-air-force-holds-joint-exercise-with-united-arab-emirates-1.5454004. “‘Medusa 11’ joint military exercise begins in Greece with participation of UAE,” Emirates News Agency – WAM, November 18, 2021, https://www.wam.ae/en/details/1395302994338,

[63] “UAE Ambassador to Cyprus attends opening of DP World’s new cruise passenger terminal,” Emirates News Agency – WAM, May 4, 2018, http://wam.ae/en/details/1395302686778.

[64] Jaffar Qassem, “Palestine vetoes UAE membership in EastMed Gas Forum,” Anadolu Agency, March 10, 2021, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/palestine-vetoes-uae-membership-in-eastmed-gas-forum/2171449.

[65] Mohamed Sabry, “UAE joins Egypt-led Eastern Med Gas Forum,” Al Monitor, December 21, 2020 , https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2020/12/egypt-uae-join-east-med-gas-forum-turkey-israel.html.

[66] Ben Fishman and Conor Hiney, “What Turned the Battle for Tripoli?,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, May 6, 2020, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/what-turned-battle-tripoli.

[67] Fehim Tastekin, “Why is Sirte everyone’s ‘red line’ in Libya?,” Al Monitor, June 19, 2020, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2020/06/turkey-libya-russia-egypt-why-sirte-everyones-red-line.html.

[68] Agnes Helou, “Iran-backed attacks are further driving UAE-Israeli defense tech development,” Defence News, February 21, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/global/mideast-africa/2022/02/21/iran-backed-attacks-are-further-driving-uae-israeli-defense-tech-development/.

[69] Amina Ismail and John Davison, “Iran attacks Iraq’s Erbil with missiles in warning to U.S., allies,” Reuters, March 13, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/multiple-rockets-fall-erbil-northern-iraq-state-media-2022-03-12/.

[70] Danny Citrinowicz, “Israel and Iran need to turn down the heat. The UAE could be the best choice as conduit,” Atlantic Council, March 21, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/israel-and-iran-need-to-turn-down-the-heat-the-uae-could-be-the-best-choice-as-conduit-%EF%BF%BC/.

[71] “As Protests Continue In Iran’s Khuzestan, Unrest Can Spread Elsewhere,” Iran International, July 25, 2021, https://old.iranintl.com/en/iran/protests-continue-irans-khuzestan-unrest-can-spread-elsewhere.

[72] Nadereh Chamlou, “Can President Ebrahim Raisi turn Iran’s economic Titanic around?,” Atlantic Council, February 1, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/can-president-ebrahim-raisi-turn-irans-economic-titanic-around/.

[73] Olivia Glombitza and Luciano Zaccara, “The Islamic Republic’s Foreign Policy through the Iranian Lens: Initiatives of Engagement with the GCC,” The International Spectator 56, n.4 (2021): 15-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2021.1986296.

[74] Reza Vaisi, “Iran, the GCC, and the failure of HOPE,” Middle East institute, September 24, 2020, https://www.mei.edu/publications/iran-gcc-and-failure-hope.

[75] Alex Vatanka, “Iran’s regional agenda and the call for détente with the Gulf states,” Middle East institute, March 17, 2022, https://www.mei.edu/publications/irans-regional-agenda-and-call-detente-gulf-states.

[76] Banafsheh Keynoush, “Iran and Yemen’s Houthis Openly Align Their Interests for Leverage in Nuclear Talks,” Inside Arabia, February 16, 2022, https://insidearabia.com/iran-and-yemens-houthis-openly-align-their-interests-for-leverage-in-nuclear-talks/.

[77] “Leaders of Turkey, Greece hold talks in rare meeting,” Associated Press, March 13, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-business-turkey-istanbul-middle-east-509aa3407ee271ee88735b3d8b725dbe.

[78] Tuvan Gumrukcu, “Turkey, Armenia hold ‘constructive’ talks on mending ties,” Reuters, March 12, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/turkish-armenian-foreign-ministers-meet-amid-efforts-mend-ties-2022-03-12/.

[79] Ayla Jean Yackley, “Erdogan hails ‘turning point’ in Turkey-Israel relations,” Financial Times, March 9, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/f011ce5e-56c6-4c28-8f13-b9b8f9612a24.

[80] Kemal Kirişci and Dan Arbell, “President Herzog’s visit to Ankara: A first step in normalizing Turkey-Israel relations?,” Brookings, March 7, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2022/03/07/president-herzogs-visit-to-ankara-a-first-step-in-normalizing-turkey-israel-relations/.

[81] Abdurrahman Şimşek, “Intelligence thwarts Iranian attempt on Israeli-Turkish businessman,” Daily Sabah, February 11, 2022, https://www.dailysabah.com/turkey/investigations/intelligence-thwarts-iranian-attempt-on-israeli-turkish-businessman.

[82] Lahav Harkov, “US informs Israel it no longer supports EastMed pipeline to Europe,” The Jerusalem Post, January 18, 2022, https://www.jpost.com/international/article-693866.

[83] Danny Zaken, “Israel and Turkey sign business cooperation MoU,” Globes, March 6, 2022, https://en.globes.co.il/en/article-israel-and-turkey-sign-business-cooperation-mou-1001404580.

[84] “Turkey, Israel vow greater potential in endeavor to boost trade,” Daily Sabah, March 9, 2022, https://www.dailysabah.com/business/economy/turkey-israel-vow-greater-potential-in-endeavor-to-boost-trade.

[85] Karel Valansi, “Turkey is seeking a fresh start with Israel,” Atlantic Council, March 10, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/turkeysource/turkey-is-seeking-a-fresh-start-with-israel/.

[86] Daniel Brumberg, “Israel and Turkey Ponder the Costs and Benefits of Rapprochement,” Arab Center Washington DC, February 25, 2022, https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/israel-and-turkey-ponder-the-costs-and-benefits-of-rapprochement/.

[87] Lahav Harkov, “Bennett, Sisi and MBZ gather in Sharm El-Sheikh,” The Jerusalem Post, March 22, 2022, https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/article-702000.

[88] Amani Hamad, “Abu Dhabi Crown Prince meets Egypt’s president, Jordan’s king, Iraqi PM in Aqaba,” Al Arabiya English, March 25, 2022, https://english.alarabiya.net/News/gulf/2022/03/25/Abu-Dhabi-Crown-Prince-meets-Egypt-s-president-Jordan-s-king-Iraqi-PM-in-Aqaba-.

[89] “Top U.S. diplomat flies to Israel for summit with 4 Arab states,” Reuters, March 26, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/washingtons-top-diplomat-meet-with-israels-bennett-2022-03-26/.

[90] Radwan Ziadeh, “Rehabilitation of the Assad Regime,” Arab Center in Washington DC, December 15, 2021, https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/rehabilitation-of-the-assad-regime/.

[91] Kinda Makieh, “UAE firms scout trade at Syria fair, defying U.S. pressure,” Reuters, August 31, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-emirates-idUSKCN1VL0HB.

[92] “Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed meets President of Syria,” The National, November 9, 2021, https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/government/2021/11/09/sheikh-abdullah-bin-zayed-meets-president-of-syria/.

[93] “Syria’s Assad visits UAE, first trip to Arab state since war began,” Reuters, March 19, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/syrian-president-assad-met-dubai-ruler-syrian-presidency-2022-03-18/.

[94] Aziz El Massassi, “US says ‘troubled’ by Assad visit to ally UAE,” Al Monitor, March 18, 2022, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/03/us-says-troubled-assad-visit-ally-uae#ixzz7OuckM0Qo.

[95] Simon Mabon, “Whither Rapprochement? Understanding Saudi-Turkish relations,” Al Sharq Forum, March 28, 2022, https://research.sharqforum.org/2022/03/28/saudi-turkish-relations/.

[96] “Saudi Arabia sets the stage for tactical outreach to Iran,” Tehran Times, May 5, 2021, https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/460619/Saudi-Arabia-sets-the-stage-for-tactical-outreach-to-Iran.

[97] Jonathan Fenton-Harvey, “The UAE Defies Saudi Arabia and Entrenches Further in Yemen,” Inside Arabia, October 7, 2021, https://insidearabia.com/the-uae-defies-saudi-arabia-and-entrenches-further-in-yemen/.

[98] Bader Al-Saif, “Battle of the Barrels,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, July 7, 2021, https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/84902.

[99] Hani Findakly, “Defusing Saudi Arabia-UAE tensions through economic rebalancing,” Atlantic Council, September 13, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/defusing-saudi-arabia-uae-tensions-through-economic-rebalancing/.

[100] “Saudi Arabia, Kuwait call for negotiations with Iran over Dorra gas field demarcation,” Arab News, April 13, 2022, https://arab.news/cu9cp.

[101] Amjad Ahmad, “Saudi Arabia and the UAE are economic frenemies. And that’s a good thing,” op. cit.

[102] Afshin Molavi, “The “Economy First” Doctrine,” U.S.-U.A.E. Business Council, February 4, 2022, http://usuaebusiness.org/publications/the-economy-first-doctrine/.

[103] “Crude Petroleum in United Arab Emirates,” Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-product/crude-petroleum/reporter/are#:~:text=2020)%20%2440.6B-,In%202020%2C%20United%20Arab%20Emirates%20exported%20%2442B%20in%20Crude,South%20Korea%20(%243.18B), accessed March 25, 2022.

[104] Mohammad Barhouma, “The Reshaping of UAE Foreign Policy and Geopolitical Strategy,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 4, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/86130.

[105] Jean-Loup Samaan, “The Shift That Wasn’t: Misreading the UAE’s New “Zero-Problem” Policy,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 8, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/86398.