One of the more enduring myths in the Gulf is that oil is so plentiful – every household has an oil well in their backyard. This webinar will explore the reality behind the five most common myths about energy in the Gulf. It will also consider how these myths impact upon perceptions and policies for domestic development and international affairs. Come along to see if you can discern fact from fiction.

Speaker: Dr Li-Chen Sim, Khalifa University

Dr Li-Chen Sim is an Assistant Professor at Khalifa University in the UAE. She is a specialist in the political economy of Russian and Gulf energy and its intersection with international relations. Her research interests include Gulf-Asia exchanges, Russia-China relations in the Middle East and Russia-Gulf interactions. Her most recent book Low Carbon Energy in the Middle East and North Africa was just published by Palgrave last month. Dr Sim holds a PhD from Oxford University.

Dr Li-Chen Sim is an Assistant Professor at Khalifa University in the UAE. She is a specialist in the political economy of Russian and Gulf energy and its intersection with international relations. Her research interests include Gulf-Asia exchanges, Russia-China relations in the Middle East and Russia-Gulf interactions. Her most recent book Low Carbon Energy in the Middle East and North Africa was just published by Palgrave last month. Dr Sim holds a PhD from Oxford University.

Listen to the full event here:

Watch the full event here:

A summary of Session 2’s proceedings can be found below.

Bridging the Gulf Session 2: Top Five Myths about Energy in the Gulf

By Herman Lim, Research Assistant, Middle East Institute, National University of Singapore

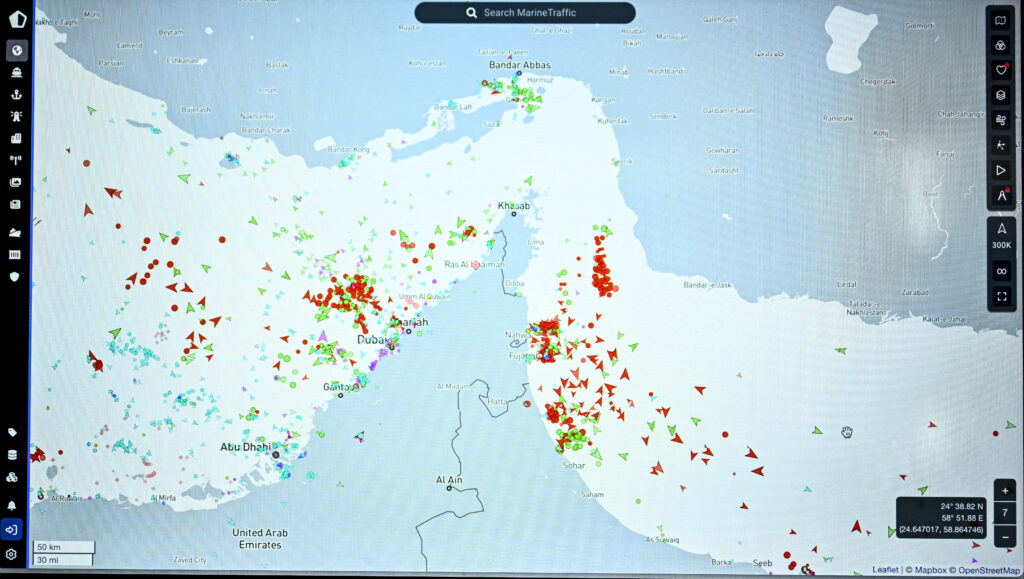

The 2nd episode of MEI’s Bridging the Gulf series focuses on some of the top myths people outside of the Gulf have about energy in the region. Host of the series, MEI Research Fellow Clemens Chay first set the stage by discussing inter-regional crude oil trade flows between the Middle East and Asia. Developing East Asian economies are among the fastest in the world, partly been fuelled by incremental oil demand in the region with China and India being the most important consumers of oil. This oil, of course, comes from Iran, Iraq, Kuwait,

Saudi Arabia and the UAE—in short, the Gulf.

Singapore is intimately linked to the oil industry of the Gulf as all Middle Eastern crude oil is valued and priced by S&P Platts, a price reporting agency based in the Southeast Asian city-state. Dr Vivian Balakrishnan, the country’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, has remarked that trade is Singapore’s lifeblood and most of its energy needs are imported from abroad.

Introducing Dr Li-Chen Sim, Dr Chay asked her the question about which country is Singapore’s largest source of oil imports?

Myth 1: Saudi Arabia is the largest oil producer

Addressing Dr Chay’s question, Dr Sim believed that most Singaporeans would say that Saudi Arabia is Singapore’s largest source of oil imports. This plays into the first myth that she wished to discuss – Saudi Arabia being the largest oil producer in the world.

While it is true that Saudi Arabia was the largest oil producer in the world for many years, that title has gone to the United States since 2017, whose global share of the oil sector has increased from 8 per cent to 18 per cent. Saudi Arabia’s share, on the other hand, has gone down from 13 per cent to 12.4 per cent. Singapore, in fact, gets most of its oil imports from the UAE today.

Dr Sim also wanted to highlight the difference between oil production and oil exports. Countries need not export all the oil they produce since some of the oil can be consumed domestically. Is Saudi Arabia, then, the biggest oil exporter in the world? This was indeed the case until 2019, where it was taken over by the UAE. One of the reasons for that is Saudi Arabia being constrained by the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) quotas. More importantly, as the country’s population grows, it consumes more oil for electricity, particularly in summertime where temperatures can go up to 44 degrees. Therefore, much of the oil produced is consumed domestically instead of being exported for rent. In fact, Saudi Arabia is the 5th largest oil consumer in the world, after the US, China, India and Japan. This is an issue that affects not just Saudi Arabia but also countries that depend on oil imports like Singapore. The UAE has been the largest exporter of oil to Singapore since 2012 and prior to that it was Saudi Arabia.

Myth 2: The Gulf is all about oil and gas

The cost of producing oil in the Gulf is one of the lowest in the world as it has a significant comparative advantage. The Gulf depends heavily on its oil revenue—it forms 60 to 80 per cent of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)’s total annual revenue. Therefore, it is partly true that the region heavily depends on oil.

However, Dr Sim stressed that the Gulf is no longer just about oil and gas today, nor can it be for long. Countries in the Gulf such as Bahrain, the UAE and Oman have created vision plans that will see their economies move towards more non-oil and gas industries. In the UAE, for example, there is a thriving steel industry with companies such as Emirates Steel leading the way. Global Foundries, the largest chip maker in the world, is also owned by Abu Dhabi. Saudi Arabia has a renewable energy giant called ACWA power, which is building renewable energy systems all over the world. Oman, on the other hand, is trying to diversify through tourism. Singaporean companies have jumped in, not just in the oil and gas industry but also in other sectors. As the Gulf diversifies over time, many more opportunities outside of oil and gas will appear.

However, do these other non-oil and gas sectors earn a lot of revenue? No, said Dr Sim—they presently cannot replace the large amounts of revenue brought in by oil and gas. When the world moves towards a post-oil and gas stage, maybe by 2050, many Gulf states will be at risk. Almost 100 per cent of Iraqi revenues, for example, are derived from the export of oil. The speed at which some Gulf states are diversifying, if at all, should be cause for alarm.

Myth 3: The Gulf is energy-secure

One would think that the Gulf is energy secure given that half of all global oil reserves and a third of all global gas reserves are in the region. The reality is the contrary, however. In Iran, before sanctions were placed, 40 per cent of all gasoline needs were imported because the country did not have enough refineries for the production of gasoline.

The other Gulf states also face similar issues. Despite having one of the lowest costs for harvesting solar energy at two cents per kilowatt hour, such capabilities have not been built up yet in the Gulf. The UAE even imports gas from Qatar for its electricity needs because the gas it owns within its reserves have a high sulphur content. The production of such gas is therefore costlier than simply importing gas from Qatar. Iraq has not been energy secure because of repeated wars and invasions, coupled with severely aging infrastructure. It therefore has to import electricity and oil from Iran. Dubai also imports coal for its coal-powered stations.

Therefore, for various reasons, the Gulf is not energy secure. Speaking about the transition to renewable energy, Dr Sim said that the Gulf can generate its own renewable energy but it does not produce the materials needed to generate such energy – like turbines, solar panels and inverters. Hence, these items must be imported and will be a significant cost barrier for the Gulf states.

Myth 4: Petrol is cheaper than water

When subsidised, petrol prices in the Gulf are less than US$0.30 cents per litre while a litre of bottled water costs about US$0.35 thus the cost of petrol can indeed be cheaper than water.

However, this reality has changed for many Gulf states as they realise subsiding petrol is using up a lot of money. While this can result in general unhappiness, most energy economists argue that subsidies are wasteful and wrongly allocate resources. These are monetary resources that can be channelled elsewhere, such as for the creation of a viable renewable energy sector. The UAE has done away with subsidies altogether, for example.

But there is equally a case for holding onto oil subsidies in the Gulf, argued Dr Sim. Since they can afford it, the subsidy of petrol gives the Gulf states a comparative advantage and incentivises MNCs to set up their businesses there. Delivery companies can operate with high profit margins because the cost of petrol is cheap. In their attempts to diversify and attract businesses, the Gulf states can make a strong case for retaining these subsidies.

However, Dr Sim mentioned that not all Gulf states can afford these subsidies. Qatar, the UAE and Kuwait for example, are much richer and have robust sovereign wealth funds which they have saved up over the years through their sale of oil and gas. Countries that are not so well off include Oman and Bahrain, whose hydrocarbon resources are quickly dwindling away. Saudi Arabia sits in between, for while they draw in huge revenues from oil and have a good sovereign wealth fund, they also have a big population. Therefore, the number of subsidies needed, per capita, to keep petrol costs low would be very high.

Myth 5: Gulf countries are lucky to have oil

Many argue that oil has enabled Gulf countries to have a high purchasing power and to build up their reserves for future generations. They rank high in the Human Development Index and have great medical systems. Citizens are thought to be well taken care of and jobs for them are guaranteed. With no income taxes, global polls often say that Gulf citizens are among the “happiest” in the Arab world. It is therefore no wonder that the Gulf countries are lucky to have oil.

Pushing back against such an idyllic view, a more useful question, said Dr Sim, would be: In what ways are they ‘lucky’?

The Gulf states that produce oil and gas have been economically worse off than the rest of the MENA region during the pandemic. They have experienced a much steeper fall and a much slower economic recovery thus far. This is because they are subject to revenue volatility—oil prices fluctuate, making it difficult to plan ahead because it is hard to determine how much revenue the government will have in the next few years. While Gulf states try to smooth out this volatility with value-added taxes, their oil industries are so efficient that it crowds out other non-oil tradeable sectors. Local industries that could have used funds from banks do not receive the loans that they need because these banks are more interested to fund oil and gas-related companies. Expatriate labour force is also crucial in the Gulf states for it competes in the global market with other countries like Singapore for talent. When oil and gas revenue falls in the next few decades, will they still be able to attract the same expatriate labour force? This is a major concern for many Gulf states who are presently oil-rich and therefore the assumption that the Gulf states are ‘lucky’ to have oil may have been true once but it is increasingly becoming an economic crutch.

Dr Sim ended her presentation by stressing the ever-changing nature of the Gulf region. Today, it is no longer just about oil and gas and a ‘one-trick camel’. The Gulf states have moved into exploring renewable energy and other non-oil and gas sectors in their attempts to diversify their economy and such moves will open up even greater opportunities in the near future for Singapore firms and the economy.