*By Gina Bou Serhal and Kristian Alexander

For decades, Japan’s scarcity of natural resources has forced the country to remain dependent on imports to meet 90 per cent of its domestic energy security needs. Japan’s densely-populated cities, mountainous terrain and steep shorelines are unfavourable for domestically -produced renewable resources.[1] Despite its target of achieving net-zero by 2050, oil and gas continue to account for 85 per cent of Japan’s primary energy mix.[2] This reliance has deepened Japan’s economic ties to the resource-rich Arab Gulf states.

Japan remains the world’s fifth-largest buyer of crude petroleum, spending nearly US$54.9 billion annually, and oil ranked as its number-one imported product in 2021.[3] A significant portion of its energy needs comes from the Gulf: Saudi Arabia supplies 43 per cent, the United Arab Emirates 30 per cent, while Kuwait and Qatar both account for 9 per cent.[4] Japan is the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company’s (Adnoc’s) largest importer of oil and gas products.[5] It also ranked as the world’s largest liquified natural gas (LNG) importer in 2022 — this accounts for the largest share of Japan’s energy mix, at 31.7 per cent, in 2022.[6] In 2021, Qatar served as Japan’s third-largest supplier of LNG, at 12 per cent.[7]

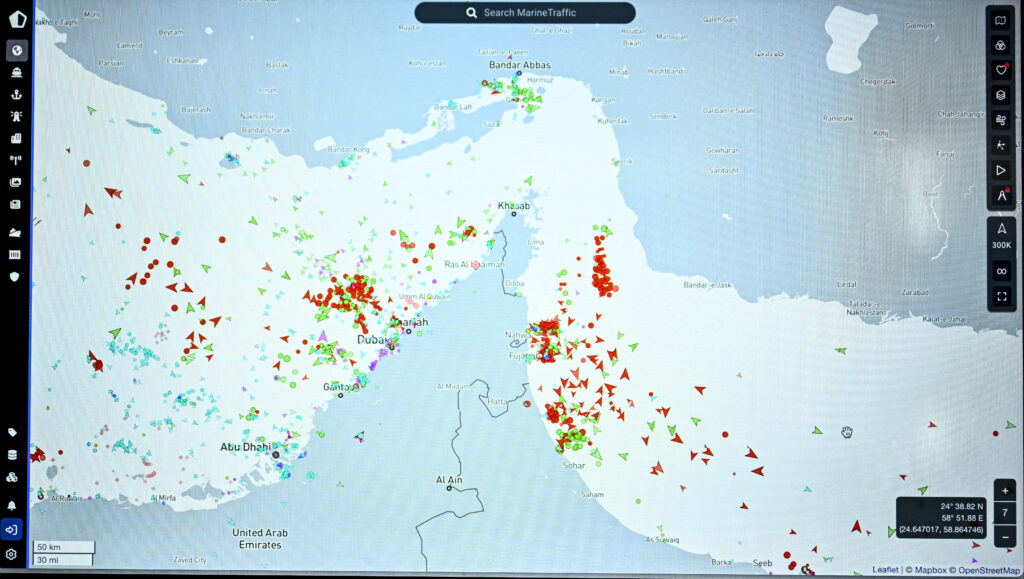

Given Japan’s reliance on the Middle East for hydrocarbons, regional stability within the Gulf remains central to its energy security strategies, as 95 per cent of its crude oil from the Gulf[8] reaches it by way of the Strait of Hormuz. It has thus contributed to the maritime security of the Gulf region: In 2020, as tensions remained high in the Middle East, Japan deployed warships to the Gulf of Aden and other waters near the region to ensure safe passage for Japanese commercial ships and oil tankers. Then-Prime Minster Shinzo Abe said the Japanese government would be prepared to authorise force to protect the country’s vessels if threatened,[9] a statement that proved controversial because of its pacifist ideology in the wake of World War II.

Japan’s pacifist doctrine is tied to Article 9 of its Constitution, which renounces military force as a means of settling international disputes[10] – an article imposed upon it by the United States in 1947. Although this has resulted in decades of peace, for many Japanese leaders and the people, it has been a “humiliating reminder of both the bitterness of a lost war and the disgrace of a military occupation”[11] by the US, which lasted from 1945 to 1952.[12]

In 2015, Mr Abe championed substantial defence policy reforms known as the “Legislation for Peace and Security,” which enabled Japan to respond to any situation in order to protect both the livelihood of the Japanese people and to contribute to global security. The legislation also introduced conditions where the use of force would be permitted as a means of self-defence if actions threaten Japan’s survival or are deemed a “clear danger to fundamentally overturn people’s right to life, liberty and pursuit of happiness”.[13]

Following repeated attacks against commercial oil tankers in the Gulf in 2019, Japan deployed a warship and two patrol aircraft for intelligence gathering in an attempt to protect oil shipments in the Gulf of Oman. Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary, Yoshihide Suga, indicated that while the measure was aimed at ensuring regional peace and stability, the presence of the Japanese military was necessary to safeguard the transit of vessels related to the country.[14]

Japan has also been involved in joint military exercises with the Arab Gulf states to enhance security cooperation and capabilities. According to Dr Koji Horinuki, Senior Researcher at the Institute of Energy Economics in Japan, the country has taken a more pro-active stance in its diplomatic outreach with the Gulf as a means to secure resources and promote security cooperation. “The security of sea lanes from the Strait of Hormuz to Japan is an important issue regarding Japan’s national interest,” Dr Horinuki said, adding that it aims to play a more pro-active role in dealing with unstable regional situations, he added.[15]

In 2014, two Japanese warships docked in Port Jebel Ali in Dubai to take part in maritime exercises with the UAE Navy for the first time. Keiji Yoshida, the overall Japanese commander of the two ships, said the exercises strengthened Japan’s relationship with the UAE, while also deepening the “inter-operability between the UAE naval forces and the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force”.[16]

Japan and the UAE have since developed even deeper bilateral defence ties. In 2018, the two countries signed a defence exchange, and in 2019, the Japanese Chief of Joint Staff, Koji Yamazaki, made his first official visit to the Emirates. General Yamazaki met both the former Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, now President, Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed, and the UAE’s Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces, Lieutenant-General Hamad Mohammed Thani Al Rumaithi.[17] In May this year, the two countries signed an accord to facilitate the transfer of defence equipment and technology. While Japan has similar agreements with the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia, it was the first time it had signed such a pact with a Middle Eastern country.[18] According to Japan’s Foreign Ministry, the agreement is expected to “contribute to closer bilateral defence equipment and technology cooperation, and maintaining and improving the production and technological bases for Japan’s defence industry, thereby contributing to the security of Japan”.[19]

The UAE is not the only country in the region that Japan has sought closer defence ties with. Around the same time as the naval exercise with the UAE in 2014, Mr Abe also travelled to Bahrain, Kuwait, and Qatar to discuss the need to promote security and defence cooperation. Japan signed defence exchange memorandums with Bahrain in 2012, Qatar in 2015, and Saudi Arabia in 2016.

The Ukraine War’s Effect on Japan’s Security Environment

Prior to the war in Ukraine, Russia was Japan’s fifth-largest oil and gas supplier in 2021.[20] Tokyo made substantial investments in Sakhalin-1 and Sakhalin-2 — an oil and gas consortium on Sakhalin Island in Russia — in 2008 in hopes of solidifying Russia as a strategic energy partner. Japanese shareholders Mitsui & Co and Mitsubishi Corp currently hold a combined 22.5 per cent stake in Sakhalin-2,[21] with nearly 60 per cent of the LNG produced there going to Japan. Considering Sakhalin’s geographical proximity to Japan, the project contributes significantly to the nation’s energy security.[22] The Japanese government has long strived to diversify its energy mix, and Russian petroleum served to lessen its dependence on Middle East supplies. The country’s energy security concerns often serve as the underlying narrative that drives its foreign policy decision-making, and Tokyo remained hesitant to impose an embargo on Russian oil following the outbreak of war in Ukraine, despite criticising the invasion.

However, following Japan’s presidency of the G7 Summit this past May, the country doubled down on its condemnation of Russia in support of Ukraine by announcing additional sanctions in coordination with its fellow G7 members in response to the invasion. Japan also announced it would be banning the provision of construction and engineering services to Russia, without providing further details, such as whether the decision would include natural gas infrastructure for its joint consortium projects.[23]

Nevertheless, Japan has since returned to importing Russian oil at prices well above the US$60-a-barrel cap imposed by the US, European Union, and Australia. The US approved Tokyo’s resumption of Russian crude purchases because of the country’s lack of options, but the situation further explains why a swift clean energy transition is just as crucial for national security purposes as it is for the well-being of the planet.

The war in Ukraine struck an unpleasant chord with the Japanese government for reasons other than energy. “[Japan] is earnest when it expresses concern that a Ukraine crisis today could be a Taiwan crisis tomorrow,” said James Brown, associate professor of political science at Temple University in Tokyo.[24] He added that the Japanese leadership was “shocked” by the war. Indeed, following the onset of hostilities last February, the Kishida administration immediately joined the West in imposing unprecedented economic sanctions on Moscow. It also issued a ban on new investments in Russia, including in the energy sector.

The deteriorating security environment in Asia and elsewhere compelled Japan to take on a more pro-active role in global affairs. The once pacifist state fears that a free, open and stable international order is in jeopardy because of “serious challenges amidst historical changes in power balances and intensifying geopolitical competition”.[25] In December 2022, Japan released its latest National Security Strategy (NSS),[26] which stressed that the world is reaching a historical inflection point in the face of the most “severe and complex security environment since the end of WWII”. The 36-page document addresses Japan’s security challenges in the Indo-Pacific, including concerns that China would consider unilaterally “changing the status quo by force” in the East and South China Seas, and North Korea’s rapidly advancing missile technologies, including its resolve to bolster its nuclear capabilities, which Japan views as a threat to its national security. In response to North Korea’s announcement in May 2023 of its plans to launch a “reconnaissance satellite” into orbit, Japan’s Defence Ministry said it would destroy any North Korean missile disguised as a “satellite” that enters its territory.[27] Although the purported satellite failed and crashed into the sea shortly after launch, Japan’s statement signals the tougher approach it is taking to counter regional security threats.

Japan’s updated strategic policies include enhancing its diplomatic strength while continually looking for global partners to ensure a “highly predictable international environment.” The government also intends to reinforce its defence capacities to deter and defeat threats and fortify its economic standing, which it views as the foundation to a peaceful and stable security environment.

The latest NSS, the first since 2013, outlines the necessary framework to strengthen Japan’s defence capabilities. Its strategy is to integrate traditional ground, maritime, and air forces with new domains such as space, cyberspace, and electromagnetic defence to deal with security threats. It also announced that it would increase its defence budget, from 1 to 2 per cent of its GDP, by 2027, in line with much of the West. The Ministry of Defence also announced the country’s largest military build-up since WWII, a five-year, $320 billion spending plan[28] that would make Japan the world’s third-largest military spender after the US and China.[29] In its latest National Defence Strategy, the country has outlined its intent to acquire counterstrike capabilities, which it claims would enable its defence forces to pre-empt enemy attacks — a change from its policy since 1956, which forbids its military from striking enemy bases unless it is determined that there is no other means to defend against an imminent attack.[30]

Japan views its alliance with the US as indispensable for the security of the Indo-Pacific region, especially with the growing threat of China and North Korea. To strengthen this partnership, Japan announced plans this May to establish a Nato diplomatic mission in Tokyo, the first of its kind in Asia, drawing a sharp, if predictable, response from China.[31] Relations between Japan and Nato began to flourish during the 1990s , when it emerged as one of the alliance’s top international partners. The country has maintained a strong interest in training and inter-operability with Nato members, specifically in the maritime security realm.[32] The announcement of the Tokyo liaison office is part and parcel of the Kishida government’s strategic national security reset from 2022, and could be perceived as a means to counter-balance China’s rising assertiveness throughout the Indo-Pacific, which Japan views as a growing threat to its territorial sovereignty. The decision also underscores Japan’s desire to achieve global recognition as an influential player which can operate effectively in a multilateral environment.

Energy Independence: Japan’s Path to Self-Sufficiency

Since the 1960s, Japan has remained reliant on fossil fuels from abroad. The ongoing global energy crisis is a stark reminder to the Japanese government that a rapid transition to clean energy and decarbonisation remain critical to achieving sustainable energy independence in the midst of a rapidly-evolving global security environment.

In October 2021, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry published its latest Strategic Energy Plan, a roadmap that aims to reduce the country’s overall emissions by 46 per cent and increase renewable energy from 24 per cent today to 38 per cent by 2030.[33] As a result of increasing LNG prices, Japan is also aiming to re-activate its domestic nuclear energy programme, which it had aimed to phase out after the Fukushima disaster in 2011. Prior to the accident, 54 nuclear reactors supplied 30 per cent of Japan’s electricity needs; now, only 10 are back online, producing less than 10 per cent of the country’s power.[34] The country wants to increase this to 22 per cent by 2030, but might find it difficult to persuade the public to go along with this plan. Polling conducted by the Japan Atomic Energy Relations Organization in 2019 revealed that, out of 1,200 respondents, 60.6 per cent believed that Japan should eliminate the use of nuclear energy in the future.[35]

Considering Japan’s limited natural resources and the current energy crisis, the country is taking a realistic approach towards a clean energy transition. Japan’s strategy remains to build a robust, self-sufficient energy system that ensures that it can withstand global shocks and unexpected contingencies. To this end, it wants to build on its maritime and defence capabilities to establish a stable and predictable security environment that can enable its economy to thrive.

Japan’s new push to build alliances in the Gulf is thus a win-win strategy. Advancing bilateral relations with Gulf states would safeguard its immediate energy needs. At the same time, Tokyo can develop strategic partnerships with countries such as the UAE to develop new technologies that optimise carbon capture and storage as it seeks to meet its ambitious 2050 net-zero target.

Image Caption: Major General Mubarak Saeed Ghafan Al Jabri, Assistant Undersecretary for Support and Defence Industries at the Ministry of Defense, and Akio Isomata, ambassador of Japan to the UAE, signing a defence cooperation agreement in Abu Dhabi on 26 May 2023. Photo: Hazem Hussein / Hatem Mohamed / Emirates News Agency

About the Author

* Gina Bou Serhal is a Researcher at TRENDS Research & Advisory, Dubai, UAE. Dr Kristian Alexander is a Senior Fellow and Director of the International Security & Terrorism Program at TRENDS.

End Notes

[1] Fatih Birol, “Japan will have to tread a unique pathway to net zero, but it can get there through innovation and investment,” International Energy Agency, June 28, 2021, https://www.iea.org/commentaries/japan-will-have-to-tread-a-unique-pathway-to-net-zero-but-it-can-get-there-through-innovation-and-investment

[2] Asia Natural Gas and Energy Association, “Japan – an Energy Snapshot,” Date retrieved: May 31 2023, https://angeassociation.com/japan-gas-policy-brief/

[3] Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), “Japan,” Date retrieved May 16 2023, https://oec.world/en/profile/country/jpn

[4] Rocky Swift and Yuka Obayashi. “Explainer: Why Japan’s power sector depends so much on LNG,” Reuters, March 10, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/why-japans-power-sector-depends-so-much-lng-2022-03-10/

[5] Dania Saadi, “UAE’s ADNOC awards concession to Japan’s Cosmo amid production capacity ramp-up,” S&P Global, February 10, 2021, https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/021021-uaes-adnoc-awards-concession-to-japans-cosmo-amid-production-capacity-ramp-up

[6] Institute for Sustainable Energy Practices “2021 Share of Electricity from Renewable Energy Sources in Japan (Preliminary),” May 04 2022, https://www.isep.or.jp/en/1243/

[7] Rocky Swift and Yuka Obayashi. “Explainer: Why Japan’s power sector depends so much on LNG,” Reuters, March 10, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/why-japans-power-sector-depends-so-much-lng-2022-03-10/

[8] Yuka Obayashi, “Japan’s dependency on Middle East crude reaches 94.5% in August-METI,” Reuters, August 2022. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/japans-dependency-middle-east-crude-reaches-945-august-meti-2022-09-30/#:~:text=TOKYO%2C%20Sept%2030%20(Reuters),industry%20ministry%20said%20on%20Friday.

[9] Tim Kelly, “Japanese warship departs for Gulf of Oman to protect commercial vessels,” Reuters, February 2, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/mideast-iran-japan-idUSL4N2A038C

[10] “The Constitution of Japan,” Date retrieved May 17, 2023, https://japan.kantei.go.jp/constitution_and_government_of_japan/constitution_e.html#:~:text=Article%209.,means%20of%20settling%20international%20disputes.

[11] John M. Maki. The Constitution of Japan: Pacifism, Popular Sovereignty, and Fundamental Human Rights, Law and Contemporary Problems, Vol. 53: No. 1, Winter 1990, https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4024&context=lcp

[12] Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute. Occupation and Reconstruction of Japan, 1945–52, Date retrieved, June 22, 2023. United States Department of State, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/japan-reconstruction#:~:text=After%20the%20defeat%20of%20Japan,%2C%20economic%2C%20and%20social%20reforms.

[13] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Japan’s Legislation for Peace and Security,” Date retrieved May 17, 2023, https://www.mofa.go.jp/fp/nsp/page1we_000084.html#:~:text=Japan’s%20Legislation%20for%20Peace%20and%20Security&text=was%20adopted%20by%20Cabinet%20Decision,Legislation%20for%20Peace%20and%20Security%E2%80%9D.

[14] Tim Kelly, “Japan won’t join U.S. coalition to protect Middle East shipping, will send own force,” Reuters, October 18 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-iran-japan-ships-idUSKBN1WX0TQ

[15] Dr Koji Horinuki, personal communication, February 10, 2023.

[16] Caline Malek, “Japanese warships at Jebel Ali for exercises with UAE Navy,” The National, October 23 2014, https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/japanese-warships-at-jebel-ali-for-exercises-with-uae-navy-1.269562

[17] Japan Ministry of Defense, “Chapter Three: Security Cooperation,” in Defense of Japan 2019, Date Retrieved: May 29 2023, https://www.mod.go.jp/en/publ/w_paper/wp2019/pdf/DOJ2019_3-3-1.pdf

[18] “Japan, UAE sign agreement to transfer defense equipment and technology,” Arab News, May 25, 2023, https://www.arabnews.com/node/2310406/world

[19] Ibid.

[20] Daniel Leussink, Ju-min Park, Chang-Ran Kim and Shinji Kitamura, “Japan’s top business lobby says difficult to replace Russian oil immediately,” Reuters, March 7, 2022, https://shorturl.at/ahmqB

[21] Katya Golubkova and Yuka Obayashi, “Russia’s Sakhalin 2 may double LNG revenue as top buyers stay despite Ukraine crisis,” Reuters, January 26, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/russias-sakhalin-2-may-double-lng-revenue-top-buyers-stay-despite-ukraine-crisis-2023-01-25/

[22] Mitsubishi Corporation, “Sakhalin-2,” Date retrieved: June 1, 2023, https://www.mitsubishicorp.com/jp/en/bg/natural-gas-group/project/sakhalin-2/

[23] Kantaro Komiya. May 26, 2023. Japan ramps up Russia sanctions with G7, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/world/japan-slap-additional-sanctions-russia-after-g7-summit-bulletin-2023-05-26/

[24] Clara Tan, “War Imperils Japan’s Energy Security,” Energy Intelligence, February 2, 2023, https://www.energyintel.com/00000186-0640-d2f7-a387-afda49e60000

[25] Japanese Ministry of Defense, “National Security Strategy of Japan,” December 2022, https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/siryou/221216anzenhoshou/nss-e.pdf

[26] Ibid.

[27] Emiko Jozuka. May 29, 2023. Japan warns it will destroy any North Korean missile that enters its territory after Pyongyang signals satellite launch imminent, CNN, https://edition.cnn.com/2023/05/29/asia/japan-north-korea-rocket-launch-intl-hnk-ml/index.html#:~:text=Japan’s%20Defense%20Ministry%20warned%20on,May%2031%20and%20June%2011.

[28] Richard Javad Heydarian, “Japan Is Quietly Becoming a Regional Security Power,” World Politics Review, April 20 2023, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/kishida-japan-military-pacifism-politics-china-tensions-foreign-policy/

[29] Tim Kelly and Sakura Murakami, “Pacifist Japan unveils biggest military build-up since World War Two,” Reuters, December 17 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/pacifist-japan-unveils-unprecedented-320-bln-military-build-up-2022-12-16/

[30] Ministry of Defense, “National Defense Strategy,” Government of Japan, December 16 2022, https://www.mod.go.jp/j/approach/agenda/guideline/strategy/pdf/strategy_en.pdf

[31] Kantaro Komiya and Satoshi Sugiyama, “Japan won’t join NATO, but aware of liaison office plan — PM,” Reuters, May 24, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/japan-wont-join-nato-local-office-considered-pm-kishida-says-2023-05-24/

[32] North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Relations with Japan,” February 10, 2023, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_50336.htm

[33] Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, “Outline of Strategic Energy Plan, Agency of National Resources and Energy,” October 2021, https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/en/category/others/basic_plan/pdf/6th_outline.pdf

[34] Shoko Oda, “Nuclear power revival reaches Japan, home of the last meltdown,” The Japan Times, March 6, 2023, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/03/06/national/nuclear-power-revival/

[35] Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, “Public Perception and Acceptance of Nuclear Power,” in Murakami, T. and. V. Anbumozhi (eds.), Public Perception and Acceptance of Nuclear Power: Stakeholder Issues and Community Solutions, ERIA Research Project Report FY2020 no.8, Jakarta: ERIA, pp.12-20, 2020.