- 18 Apr 2021

Hebrew Language and Culture Colloquium

|

|

|

|

|

Hebrew Language and Culture Studies in Southeast Asia: Current Condition and Future Prospects

This two-day online conference will explore the potential for growth of Hebrew language and culture at the university level in Southeast Asia and the possibilities for cooperation and collaboration in the learning and teaching of the Hebrew language, in order to:

- Raise the profile of the Hebrew language and culture in academic studies in Southeast Asia; and

- Generate scholarly cooperation among different institutions in Southeast Asia.

Notable experts and professionals will share their points of view from various perspectives concerning Hebrew language and culture. The speakers will be scholars of Hebrew literature and culture, Hebrew language professors and academics.

Cultural figures, artists and other prominent figures from a variety of institutions are expected to attend and participate in this event.

Participants and speakers will examine and discuss subjects concerning the relevance and potential of Hebrew language and culture as part of studies in institutions and universities in Southeast Asia.

This public talk will be conducted online via Zoom on Saturday and Sunday, 17 to 18 April 2021 from 7.30pm (SGT). All are welcome to participate. Successful registrants will receive a confirmation email with the Zoom details closer to the date of the event.

This event is free, however, registration is compulsory. To register, click here.

Please click HERE for the latest programme details.

Photo by Tanner Mardis on Unsplash

Listen to the proceedings from Day One here:

Listen to the proceedings from Day Two here:

Watch the proceedings from Day One here:

Watch the proceedings from Day Two here:

Read the Summary of Event Proceedings for Day One:

By Tan Feng Qin

Research Associate, Middle East Institute, National University of Singapore

On the first day of the colloquium (17 April), Dr Vardit Ringvald, C.V. Starr Professor in Language and Linguistics at Middlebury College, Professor Yaron Peleg, Kennedy-Leigh Reader at the University of Cambridge and Ustaz Sapri Sale, author of the Hebrew–Indonesia dictionary and a Hebrew teacher in Jakarta, discussed the teaching of culture in Hebrew language programmes, the relationship between the Hebrew language, literature and culture, the close linguistic relationship between Arabic and Hebrew and the experience of teaching and learning Hebrew in Indonesia.

Opening Speeches

Chairman of the Middle East Institute (MEI) Mr Bilahari Kausikan launched the event with a short speech. Mr Kausikan expressed his hope that the discussions held in this colloquium, the first of its kind in Southeast Asia, would lead to a better understanding of Israeli and Jewish culture in the region. He gave a short overview of Singapore’s long-standing and close ties with Israel and described Singapore’s Jewish community as an integral part of Singapore society since the nation’s founding. Just as Israel’s position has fundamentally changed for the better in the Middle East since the Abraham Accords, a similar change is long overdue in Southeast Asia. Mr Kausikan lauded Ustaz Sale as a unique individual trying to foster a better understanding between Southeast Asian Muslims and Israel and expressed his hope that the colloquium would be just the first step in this journey.

His Excellency Mr Sagi Karni, Israel’s ambassador to Singapore, then gave a short speech of his own. He expressed his admiration for Ustaz Sale’s efforts to teach Hebrew in Indonesia and was glad that the event would enable more people to know about the Hebrew language and Israeli culture and history. He described a fundamental positive change occurring in the Middle East with the Abraham Accords and expressed his hope that this change would be appreciated by the people of Southeast Asia. He said he had always found a serious interest among Indonesians to know more about Israel and to do business with Israelis, noting that nearly 40,000 Indonesians visited the country in 2019. Ambassador Karni also invited the students of Ustaz Sale to further their Hebrew language studies in Israel.

Learning Culture while Learning Language: Approaches and Challenges

Dr Ringvald began the colloquium with a presentation on the connection between language and culture, and how teachers have sought to integrate the two in their curricula. The Hebrew language is complicated and difficult. What makes teaching Hebrew even more complicated is the need to also talk about its connection to culture. Indeed, some believe that in the best language education, “the study of another language is synonymous with the study of another culture.”

As questions intensified in the 1990s on how to integrate cultural studies into language studies, language educators faced several challenges. These included how to teach culture to students with limited levels of proficiency, avoid cultural stereotypes when teaching language through generalisations to such learners and how to teach culture when it contradicts or conflicts with a learner’s own cultural values.

The School of Hebrew at Middlebury College has sought to teach Israeli culture in its language programme by teaching its students to identify and engage with elements of culture that are expressed in the Hebrew language. It has also encouraged students to develop curiosity to research Hebrew culture on their own and to acquire tools to analyse and critique it, while developing empathy and acceptance for the culture they encounter even as they examine it from their own perspective.

The school has taught Hebrew in an intensive, immersive environment, where students and even staff take a pledge to communicate only in Hebrew to allow students to constantly engage with the language and eventually use authentic Hebrew functionally in real-life settings and in its proper cultural context. It also brings to its programme a diverse group of scholars from many fields, including literature, history and anthropology, as well as creators of Hebrew culture such as poets and actors. Students engage with these experts and practitioners to better understand the culture of the language they study.

Middlebury College has sought to avoid the problem of stereotypes by approaching the teaching of language and culture in a systematic way. It has infused culturally-relevant anecdotes related to the theme or topic being studied within the curriculum for lower-level language learners. These may include critical assessments of events in Jewish history, such as the siege of Masada. Students in upper-level courses may take content-based courses in Hebrew taught by subject matter experts on a wide range of topics, from multiculturalism in Israeli society to Hebrew typography.

Culture has also been taught through co-curricular artistic, physical or sociocultural activities, giving students an opportunity to use Hebrew in a cultural context during their daily routine. This allows learners to better activate their senses, be part of Hebrew culture and even create their own cultural artefacts to look at culture as insiders and not outsiders. Students are also asked to constantly reflect on their engagement with Hebrew language and culture, whether through discussions or creative endeavours of their own.

The Development of Hebrew Culture through the Evolution of its Literature

Dr Peleg next took participants through an overview of how modern Hebrew culture developed through the evolution of its language and literature. The Hebrew language was very important for most of Jewish history as the repository of both the culture and religion of the Jewish people, who travelled and were dispersed all over the world, and the language has a long textual history embodied in venerable scrolls and volumes of religious books.

Before the modern period, much of Jewish culture revolved around a preoccupation with such religious legal texts, which were expanded upon and discussed in Hebrew. The first generation of writers in the modern period of Hebrew culture, which began in Europe in the 19th century, were men. In the traditional period, only men had access to religious education and accordingly access to the Hebrew language, making it difficult for women to become writers of Hebrew prose.

The first attempts to modernise Hebrew culture in this period involved modernising the Hebrew language. As the 20th century began, a more diverse field of writers appeared. Within this field, men were mostly writers of prose while women were mostly poets, since it had been more difficult for women to access the language. By the time the state of Israel was established, this gendered division in Hebrew literature had begun to breakdown and a mixture of both men and women began participating in the creation and expansion of the Hebrew literature.

It is important for advanced learners of Hebrew to look at Hebrew literature to understand both Hebrew culture and how the development of the language intertwined with the development of this culture. The novel The Love of Zion was published in 1853, and sought to convey Jewish modernity in biblical Hebrew language, using only words taken from the Hebrew bible as a connection to the ancient Jewish past. By 1910, a more conversational, lively and dynamic Hebrew had begun to take shape that was closer to the daily life of Jewish readers. Yosef Haim Brenner, the writer of a Hebrew novella Nerves, in many respects invented Hebrew vernacular through the dialogue of his characters, as even then, not many spoke Hebrew fluently.

Hebrew writers also engaged with the development of the state of Israel. The Prisoner, a story written by S Yizhar (Yizhar Smilansky) and published in 1949, engages moral questions emerging from Israel’s war of independence. In the 1960s, other writers expressed their ambivalence about grand, national issues and sought through their work to express a desire to disconnect from the political world. Some engaged the feminist revolution in modern Israeli culture through their poetry, while still others in the 1990s took up the perspective of Jewish immigrants from Middle Eastern countries like Egypt. Throughout the development of modern Israel, writers in Hebrew have sought to engage the relevant and pressing issues of their time through Hebrew literature, and in doing so have both engaged in the process of changing Israeli culture and documented their participation in the ongoing cultural debate.

Teaching and Learning Hebrew in Indonesia

In the last presentation of the day, Ustaz Sale gave participants insights into the close relationship between Hebrew and Arabic. He also spoke on his experience as a Hebrew teacher in Indonesia and on the challenges of learning the language in the country.

It is rare to find a Muslim teaching Hebrew in Indonesia, though there are at least three Muslim Hebrew teachers in Indonesia that Ustaz Sale knows of, himself included. Although Hebrew is an important Middle Eastern language and is a sister language of Arabic, not many in Indonesia have paid attention to the language or know that Hebrew texts have had tremendous influence on Christianity and Islam, although there has been limited study of Hebrew in Indonesia in the context of Christian theological learning at the university.

Hebrew is similar to Arabic in many ways and the two languages are very close. Many Hebrew and Arabic words, those for “horizon” and “axis” for instance, not only sound alike but also share a similar alphabet, almost as though they were copied from each other. This is also the case for verbs in the two languages. Many Arabic and Hebrew words are based on a analogous system of three root letters, which determine their meaning. The two languages also share a like method of conjugating verbs and indicating possessives. For instance, the terms for “I read” and “we read”, and for “house” and “my house” in Arabic and Hebrew are not only similarly structured, but also sound almost alike. As such, it has been Ustaz Sale’s experience that students who already know Arabic rarely face difficulties in learning Hebrew.

Hebrew is also useful for the study of Jewish lore or israeliyat (إسرائيايات) in Arabic. The study of israeliyat is popular among both modern Muslim intellectuals and in Islamic traditional schools. Knowledge of Hebrew allows one to compare Arabic narratives of Jewish lore to Hebrew narratives of the same to cross-check and clarify the two versions. In a similar way, an understanding of Hebrew could also be essential in fully comprehending commentary on the Qur’an.

In Ustaz Sale’s view, Hebrew and Arabic are similar languages that meet in Bahasa Indonesia, the lingua franca of the Indonesian islands that is based on the Malay language. Bahasa Indonesia unites the people of Indonesia, who speak more than 700 different languages, in the same way that Hebrew has united the Jewish people. It is an open question whether some words in Bahasa Indonesia, like sedekah, are ultimately derived from Arabic or Hebrew and he believed more research should be done on the issue.

There are several challenges faced by Hebrew learners in Indonesia. Chief of these is a lack of access to good Hebrew learning resources. Another is a relative lack of opportunity for learners to communicate with native Hebrew speakers, although Indonesian students have sought to communicate both with students of Hebrew universities and of Middlebury College. Some also carry negative stereotypes about Jewish culture and Israel. In addition, Southeast Asia lacks a centre of Hebrew language learning.

Ustaz Sale believed that learning Hebrew helps to promote understanding and tolerance toward the Jewish people. It lets learners recognise the closeness of the three Abrahamic religions. The language is also fun and easy to learn for those who already know Arabic. While being a Hebrew teacher as a Muslim in Indonesia has sometimes been daunting, he has enjoyed doing so.

Highlights from the Question and Answer Session and Discussion Summaries

Asked what kind of cultural bias she found most difficult to overcome as a teacher of Hebrew and how she responded to it, Dr Vardit described an encounter with some students, who disagreed with the way opinions were exchanged in an Israeli television debate that she had shared as an example of authentic Israeli culture. The students felt that the interlocutors on television did not respect one another’s opinions and what they observed of Israeli culture from this exchange persuaded them to drop the course. The incident started Dr Vardit’s journey to understand the connection between language and culture. She sought to engage those learners to better understand their perspective and used the opportunity as a way to learn more.

Asked how the trajectory of Hebrew vernacular culture has shaped the nature of the Hebrew language itself, Dr Peleg noted the unusual role of writers in the development of modern Hebrew culture. Unlike in many other languages and cultures, while Hebrew had always been used by Jews, it was for many millennia mainly used for religious ritual and study and not as a vernacular. As such, when writers started using Hebrew as a literary language during the modern period, the language as they used it provided examples for Hebrew vernacular that had hitherto been lacking, and started shaping the actual Hebrew culture that developed outside of their literature. Written Hebrew has had an outsized role in shaping Hebrew culture and in turn many poets, all the way up to the 1970s, had a very important role in modernising Hebrew by inventing words and shaping expressions that moved from the pages of their literary work into real life.

On the question of how Muslims respond to conceptions of god and religion within Judaism when learning Hebrew, Ustaz Sale replied that it is each individual’s personal task to establish their own connection with god and that he could not interfere in the matter of how an individual understood their god, including through a knowledge of the Hebrew language. He felt that being a Muslim did not preclude his being able to find matters of interest in Hebrew texts.

As the event drew to a close, presenters and participants entered smaller groups to discuss the themes of the colloquium and to share their experiences learning and teaching Hebrew. The presenters then each gave a summary of the issues discussed in their groups. The issues raised included the lack of resources in Southeast Asia that fit the profile of learners of Hebrew in the region, a desire for more opportunities and venues to gather and study the language, the matter of avoiding a connection between politics and the Hebrew language, and the importance of obtaining an education about culture through language studies.

Read the Summary of Event Proceedings for Day Two:

By Herman Lim

Research Assistant, Middle East Institute, National University of Singapore

Kicking off the second day of the colloquium, 18 Apr 2021, MEI Research Fellow Ameem Lutfi recapped how the development of modern Hebrew was tied to the specific historical context of the Ashkenazi Jewish community in 19thcentury Europe. Yet, we know that ancient Jewish communities in the diaspora existed in many places across the world, including the Middle East and North Africa, Central Asia, India and even as far as China, each with their own linguistic traditions. Thinking about the potential growth of Hebrew language learning in Asia, Dr Lutfi asked if it were possible for the learning of Hebrew in the future to revive these diverse linguistic traditions and highlight the historically cosmopolitan and polyphonic nature of Hebrew as a global language. Making reference to Sapri Sale’s talk the day before, Dr Lutfi also questioned if Hebrew can be taught alongside Arabic, in already popular Arabic language programmes in the region, as a sister language.

The Pronunciation of Hebrew from Antiquity to the Present Day

Starting off with the same interest in historical developments, Dr Khan’s talk traced the shifts in Hebraic pronunciation. He reminded the audience that Hebrew had ceased to be a vernacular language since the 3rd century C.E. and had been revived only in the 20th century. This is not to say that Hebrew became extinct in the intermediate centuries—rather, it remained alive in many other ways through its use as a written language and as an oral tradition through the verbal recitation of holy scripture. Hebrew words were also embedded within other Jewish diasporic languages and in learned discourse.

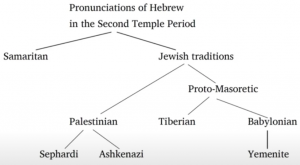

Fig. 1: Historical development of Hebraic pronunciation, from Dr Khan’s presentation

Fig. 1: Historical development of Hebraic pronunciation, from Dr Khan’s presentation

Modern Israeli Hebrew developed from Sephardic pronunciation, with connections all the way back to the Second Temple period. The Jewish traditions split mainly into Palestinian, Tiberian and Babylonian traditions. The Tiberian tradition, through its development in the Middle Ages, provided the vocalisation or vowel signs for pronouncing Hebrew. In this period, Hebrew started to be written in codices (books) as opposed to scrolls due to the influence of the Islamic tradition and the writing of the Qur’an in codex form. Some Jews even wrote with Arabic script, representing the oral tradition of Hebrew with it. After the Middle Ages, the Tiberian tradition became extinct and the Palestinian tradition became predominant. The same vowel signs, which had been created for the Tiberian tradition, were then transposed and used on the Palestinian Sephardic tradition and this ‘mismatch’ is still in place today.

With fewer people using the Tiberian tradition, the Palestinian tradition became more widespread, moving into Europe via Italy into the Rhine and travelling to Spain and North Africa. The Ashkenazi tradition then developed from the Palestinian tradition, developing its Ashkenazi features in the 14th century. The Babylonian tradition, on the other hand, had spread to Yemen. An important fact to note, said Dr Khan, is that the pronunciation of the Hebrew in different diasporic communities was affected by their other language traditions. The Hebraic pronunciation of Italian Jews for example would be influenced by the pronunciation of Italian.

In response to Dr Lufti’s question about how we can revive the polyphonic traditions of Hebrew, Dr Khan argued that students must first be aware that these traditions are still alive and that they are still pronounced orally. Students of Hebrew must move away from the myth that Hebrew is a simply revived dead language and embrace these different traditions.

When asked how modern Hebrew pronunciation will change in the future, Dr Khan stressed that all languages change, even within the span of a generation. Old Hebrew films from the 20th century already sound very different to modern Hebrew speakers. The impact of vernacular languages because of the gathering of the Jewish diaspora in Israel on modern Hebrew is also still being studied. Social-linguistic aspects also affect the development of pronunciation. Specifically, competition between the Mizrahi and Ashkenazi pronunciation within Israel have and will continue to affect modern Hebraic pronunciation over time.

A Preliminary Note on Hebrew in Indonesia: From a Sacred Language to a Metalanguage of Identity

Mr Epafras’ research covers both the use of Hebrew in the Indonesian archipelago throughout history, as well as his preliminary observations of its recent and growing use among Christian Indonesians since the 1990s. Stressing the country’s religious diversity, he started by informing the audience that there is in fact one working synagogue in Tondano, North Sulawesi and Jewish believers are free to worship as they please there.

Regarding Hebrew being first introduced in Indonesia, Mr Epafras argued that it is difficult to tell but he pointed to the work of Professor Rusmin Tumanggor, an anthropologist of health, who does research on local medicine in Barus, North Sumatra. Reported in National Geographic Indonesia, among many of his findings include the possibility that a local incantation there is of ‘Hebrew’ origin. This should not surprise us, however, because the location of Barus was mentioned in one of the manuscripts of the Cairo Genizah, a collection of millennia-old texts discovered in the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo, as the source of camphor (kapur barus in Indonesia). While the findings remain inconclusive, Mr Epafras has been working on establishing the earliest presence of Arab Jewish traders in the Indonesian archipelago, first in Srivijaya in the 10th century (as mentioned in an Arabic source) and later Barus in the 12th or 13th century (as shown in Cairo Genizah).

In the modern period, western European missionaries and Bible translators were the agents in introducing Hebrew in Indonesia, as part of Christian theological discourse. Hebrew became important in biblical hermeneutics, especially for Protestants. Many of the reformed Protestant traditions introduced by these missionaries continue to be maintained by Indonesian Protestants today, including the concept of Hebraica Veritas: that the Hebrew Bible was the ‘original’ version of the Old Testament, as opposed to Greek or Latin. Because of this belief in the centrality of the Hebrew language, many Pentecostal churches in Indonesia also adopted Hebrew in their church songs. One notable example is the Indonesian song entitled ‘Phrase Jehovah’, which follows the rhyme of Ha-Tikvah, Israel’s national anthem, thereby blurring the distinction between the Hebrew language and the modern state of Israel. In 1999, a Hebrew-Indonesian bible was also produced for academic purposes.

The Reformasi era in 1998 brought about drastic political and religious changes, including greater transnational religious discourse. Mr Epafras argued that the 1993 Oslo Accords between Israel and the Palestinian Territories stimulated a new Christian consciousness in Indonesia. It opened the possibility for Christian Indonesians to visit Israel and some of the Christian leadership embraced a Judaic subculture into their theological construction and rituals. This further intensified post-1998 with Christian Evangelical movements such as the Hebraic Roots and Sacred Namers Movement, which helped Christians identify with the Jewish roots of their faith tradition. Some Christian Indonesians now use Hebrew greetings on Facebook pages, like shalom aleichem, in the same way Muslims use assalamu ‘alaikum.

In conclusion, Mr Epafras stressed that learning Hebrew has become a reality of globalisation. Many Indonesians work for Israeli companies and there is greater engagement between Indonesian regional governments and Israel, learning Hebrew makes sense. However, the use of Hebrew has also become embroiled in wider transnational religious discourses, where it becomes entangled with Christian identity and identity politics. Growing Semitophilia (a love of Jewish culture) and a minority complex amongst Christian Indonesians might be pushing them to adopt Judaic subculture, argued Mr Epafras, as they compete with Muslims who have an ‘Arab’ subculture.

Teaching Israel through Film

Professor Kaplan argued that the medium of feature films can be a great teaching tool for understanding the Israeli society producing them at any specific moment in modern history. His talk discussed some of themes that he explores with his students in classes and how the way these themes are dealt with changes as Israeli cinema evolves, including the portrayal of the Israeli soldier and the military, the tensions between Ashkenazis (European Jews) and Mizrahis (Jews of Arab and Eastern origin) and the place of religion in Israeli society.

As most of Professor Kaplan’s students work on American cinema and want to make the next great American film, he often asks them what such an endeavour would entail. Most would typically answer that their journey would take them to Hollywood, where they would pitch ideas to producers and at some point, they would discuss the issue of funding. They are therefore mostly concerned with film as a commercial enterprise, where it has to appeal to a certain audience and generate revenue to cover the expenses of the film and hopefully profit. He then asks them, what does it take to produce the next great Israeli film?

Professor Kaplan explained that, unlike the US context, most of the budget for Israeli films in the last 40 years come from public funds in Israel, where an average of 12 to 15 films are produced annually. There is also generally no interest in creating blockbuster films that would cover the cost of the film and make a profit. Film making is viewed by the Israeli state as investing in a national industry and the success of such films is judged, not by number of tickets sold but by achieving two main international goals: Being admitted into major film festivals around the world (like Venice, Berlin or Sundance) and being nominated to the major awards (such as the Golden Globes or Oscar’s).

Therefore, for international bodies looking at Israeli films, they would be most interested in seeing stories that are unique to Israel and help viewers understand the Israeli experience. Due to the stance taken by the Israeli government in funding the production of films, Israeli films are therefore great candidates for understanding Israeli society and culture and speak to issues that matter to Israelis, including the Arab-Israeli conflict, the role of the military in Israeli life, ethnic tensions within Israeli society and the place of religion. As the budget for Israeli films is relatively low (about 1.5 to 2 million dollars, compared to the 70 to 80 million dollars of an American film), they are shot on location, with no elaborate effects or sound sets.

Elaborating further on the key theme of the representation of Israeli soldiers and the military, for example, Professor Kaplan said that most of the earlier films, even before the creation of the state of Israel in the 1940s, would depict soldiers as the pinnacle of heroism—martyrs who died in selfless sacrifice for the birth of the nation. Starting in the late 1960s, especially after the Six Day War, however, the depiction of military becomes more critical. We witness the price and toll of war on the bodies of soldiers on film. They become more focused on the individual rather than the state as a collective. Compared to Hill 24 Doesn’t Answer (1955), an epic retelling of the 1948 war, the contemporary film Waltz with Bashir (2008) does not valorise war and explores the psychological price soldiers pay for endless dubious wars, especially in the case of Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982.

Another common theme is the tension between Ashkenazis, who were the primary driving force of Zionism and the creation of the Israeli state and the waves of Jewish immigrants from Arab and Muslim countries in the 1950s to 60s—otherwise known as Mizrahi Jews. The first film to tackle this theme is Sallah Shabati (1964), a huge commercial success, gaining international recognition as a finalist in the 1965 Academy Awards. Framed as a comedy that discusses the absorption of immigrants into Israel and the challenges those immigrants face in the transitory camps they were housed in, the driving mechanism of the humour was the ethnic tensions and stereotypes pitting Ashkenazis against Mizrahis. Setting the tone of ‘Bourekas comedies’ that really defined Israeli humour in the 60s and 70s, such a treatment of the Ashkenazi-Mizrahi divide would take a turn in the 80s and 90s, where its treatment becomes much more critical. The harsh social reality that the Mizrahis faced because of their treatment by the establishment take centre stage instead.

In conclusion, Professor Kaplan argued that we are seeing a more varied spread of films as Israeli cinema develops, as more people from different communities (including Arabs and religious Jews) get to represent their voices and explore the tensions and dynamics affecting their lives and communities within the Israeli state. He believes that all Hebrew learners should take advantage of these films as learning tools for understanding Israeli society and culture.

About the Speakers

Director

School of Hebrew, Middlebury College, Vermont

Professor Yaron Peleg

Kennedy-Leigh Reader

Asian and Middle East Studies

University of Cambridge

Mr Sapri Sale

Hebrew Teacher Jakarta

Professor Geoffrey Khan

Regius Professor of Hebrew

University of Cambridge

Mr Leonard Chrysostomos Epafras

Instructor and Researcher

Universitas Kristen Duta Wacana and the Indonesian Consortium for Religious Studies (ICRS), Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Professor Eran Kaplan

Goldman Professor in Israel Studies

San Francisco State University

Mr Bilahari Kausikan is the chairman of the Middle East Institute, an autonomous institute of the National University of Singapore. Mr Kausikan was permanent secretary of Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 2010 to 2013, having served as second permanent secretary since 2001. He was subsequently ambassador-at-large until May 2018. His earlier appointments at the ministry include deputy secretary for South-east Asia, permanent representative to the United Nations in New York, and ambassador to the Russian Federation.

Ambassador Sagi Karni joined the Israeli Foreign Service in 1995. His first overseas posting had him stationed in Beijing. He then, served as the Deputy Chief of Mission in Oslo. Following which, he was a member of the Israeli delegation to the European Union in Brussels.

Dr Vardit Ringvald serves as the C.V. Starr Professor in Language and Linguistics and the Director of Middlebury’s School of Hebrew. She was appointed as the Founding Director of the Middlebury School of Hebrew in 2008, while serving as Professor of Hebrew and Director of the Hebrew and Arabic Languages Programme at Brandeis University. Dr Ringvald will be responsible for oversight and implementation of Hebrew Across America 2020 – from recruitment of the new faculty member to curricular and co-curricular design and budget administration.

Dr Yaron Peleg is Kennedy-Leigh Reader in Modern Hebrew Studies at the University of Cambridge. Professor Peleg published widely on a number of topics in modern Hebrew literature, Israeli cinema and Israeli culture more broadly, including several books and numerous articles on Israeli militarism, homoeroticism, gender, masculinity, ethnicity, class and religiosity.

Mr Sapri Sale is the author of Hebrew – Indonesia Dictionary. His exposure to Hebrew commenced when he studied Arabic literature at Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt in 1989. There, he also started learning about Hebrew at the Israeli Cultural Center. Thereupon completing the study, he spent more than ten years in numerous Arab countries and developed a high proficiency in Arabic, including local dialects. He continued to learn Hebrew during his stay in the United States and began writing Hebrew – Indonesia dictionary in 2006. He now dedicates his time teaching Hebrew in Jakarta and is the only teacher of modern Hebrew in Indonesia.

Dr Geoffrey Khan (PhD, School of Oriental and African Studies, London, 1984) is Regius Professor of Hebrew at the University of Cambridge. His research publications focus on three main fields: Biblical Hebrew language (especially medieval traditions), Neo-Aramaic dialectology and medieval Arabic documents. He is the general editor of The Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics and is the senior editor of Journal of Semitic Studies. His most recent book is The Tiberian Pronunciation Tradition of Biblical Hebrew, 2 vols, Cambridge Semitic Languages and Cultures 1 (University of Cambridge & Open Book Publishers, 2020).

Dr Leonard Chrysostomos Epafras is a Researcher and Faculty in Universitas Kristen Duta Wacana and the Indonesian Consortium for Religious Studies (ICRS), both located in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. He was a recipient of a number of fellowships including Fulbright, Endeavour and Schusterman Institute for Israel Studies. Dr Epafras teaches Judaism, Advanced Study of Christianity, and History of Religions. His research projects include the Jewish community in Indonesia, Religion Online, and Interreligious topics. His publications can be accessed at https://leonardchrysostomosepafras.academia.edu

Dr Eran Kaplan is the Goldman Professor in Israel Studies at San Francisco State University. He is the author, most recently, of Projecting the Nation: History and Ideology on the Israeli Screen (2020).