- 14 Jul 2020

Gulf–Asia Relations within the Changing Global Order

Abstract

The gradual shift in the global economic order, which is becoming increasingly apparent over the last decade, has re-oriented the contours of the Gulf–Asia relations. The rise of Asia and the Gulf, itself a part of Asia, led to a shift and restructuring of the global economy. The Gulf “Look East” policy coincided with some Asian countries’ “Look West” policy. Will this global economic shift continue? Are current crises like the Covid-19 pandemic, the consequent fall in oil prices and the global economic downturn bound to alter this trajectory and interest between the Gulf region and Asia? To what extent will the US–China cold war affect this shift? What do all of these mean for the future Gulf–Asia relations?

Join us for this public talk held in collaboration with the Gulf Studies Center at Qatar University on 14 July, 4.00pm to 6.00pm (SGT), which will be conducted online via Zoom. All are welcome to participate. An e-invite will be sent to you near the event date.

This event is free, however, registration is compulsory.

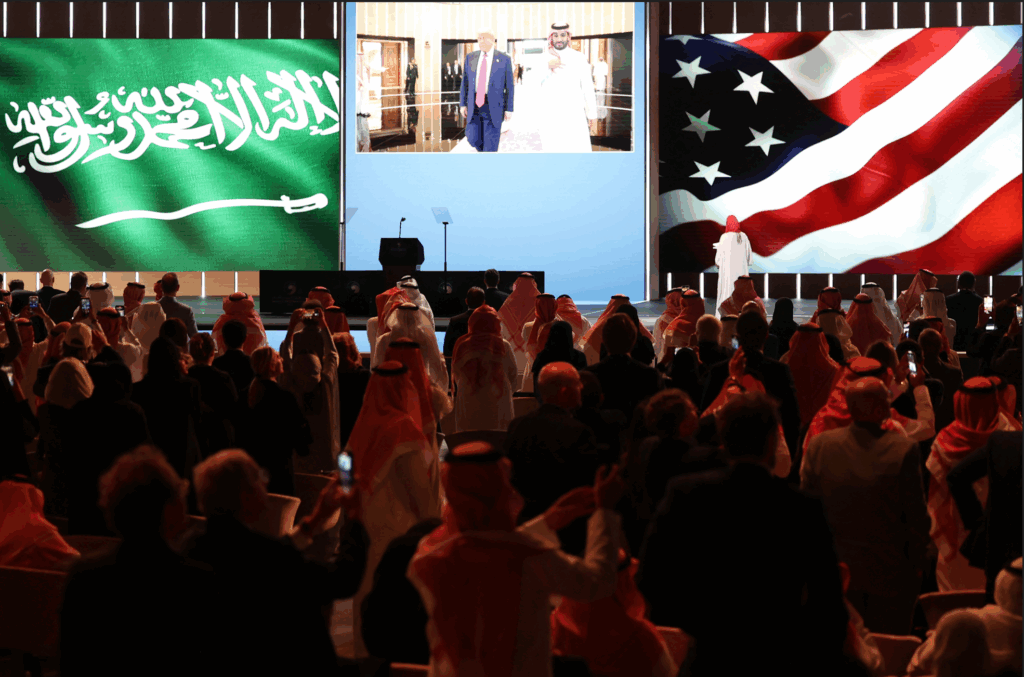

Image caption: Photo by Roman Logov on Unsplash

Listen to the full event here:

Watch the full event here:

Read the Event Summary:

By Faruq Yunus Alsagoff

Intern, Middle East Institute, National University of Singapore

In this session moderated by MEI Visiting Research Professor Abdullah Saleh Abdullah Ba Abood, six panellists unpacked the different dimensions of Gulf–Asia relations, looking at them from the perspectives of different states and from different avenues of possible co-operation.

Dr Mahjoob Zweiri

Director, Gulf Studies Center, Qatar University

In his kick-off comments, Dr Zweiri contextualised the importance of studying these developing relations in a rapidly changing global climate. The world is facing serious challenges, with states having to recalibrate policies according to changing balances of power in the international arena, both politically and economically.

In these last few months, Covid-19 came into the picture. Amid the high levels of uncertainty and anxiety, the objective of both sides the GCC and Asia is to achieve two main goals: economic and human development, and stability.

The pandemic, combined with the resultant interconnectedness of a globalised world, has shed light on the significance of human security. Human considerations are becoming increasingly important in the development of international relations and collaborations, where states now need to look for ways to develop their economies such that they can survive sustainably and provide what is needed for their people to survive during difficult times.

Another challenge brought about by globalisation would be cultural and political stability. Because of how interconnected the world is today, not only are political ideas spreading around the globe, but cultures are also moving rapidly across borders. This rapid diffusion of ideas could lead to instability in states when their people are influenced by foreign politics and cultures, applying them into contexts that may not be suited for them.

Professor Anoush Ehtesami

Professor of International Relations, Durham University

Aiming to provide a framework to facilitate the discussion, Professor Ehtesami broke down the relevance of GCC–Asia relations along four key contextual parameters: systemic shifts, the relationship between globalisation and global regions, notions of “Asianisation”, and issues of competition.

Systemic Shifts

Up until recent years, there had been very little inclination for the Gulf states to take note of Asia. The GCC–Asia relationship is itself symbolic of developments in international relations as a result of systemic shifts in the global balance of power.

There are several ways to understand these systemic shifts. Firstly, it would be to see them through the dramatic shift of the world economy eastwards. Secondly, through the rapid growth in GDP or purchasing power parity (PPP) in regions beyond Europe and North America.

Thirdly, through the rise in economic power of key non-Western economies in the global context which have, over the years, been laying the bricks to form relatively steady economic foundations. Although not all of them are prosperous, they are rising nonetheless. Fourthly, the domination in manufacturing of countries outside of the Western world, most notably in China.

Lastly, through the significant shifts in trade patterns. This builds upon the first point, and recent sentiments show that the new epicentre of the global trade have shifted from the western edges of Turkey to Iran.

Globalisation Vs Regionalisation

The relationship between globalisation and regionalisation is another vital parameter through which we can understand GCC–Asia relations. The Covid-19 pandemic is an indication of how globalised the world has become due to the intensification of integration and massive interconnectedness. There is a false assumption that globalisation has created a level playing field for all, Dr Ehtesami believes, since instead it intensifies hierarchies in the global system.

For a long time, regions have become relatively unimportant since the global context is prioritised. This is alarming since it is an important mechanism that could provide protection for countries badly affected by the pandemic, especially developing states and economies which face more difficulties than others. In the Gulf, regionalism could provide these “barriers of protection” which could alleviate some of the damage caused and help states respond appropriately to the crisis at hand.

Regionalism has also accelerated the processes of globalisation. In recent years, regions are now able to speak for their constituent countries and control their relations in the global economy. They also interact much more with one other, providing collective platforms for states to mingle, and serve as alternatives to strictly bilateral relations. As a result, the process of integration has deepened as well, to a point where global regions are dominating the international economic system.

“Asianisation”

In light of the changing dynamics of global relations, West Asia has “woken up” to its Asian heritage. For the past century or more, the Middle East had looked Westward in all regards. Culture, economics, security and politics in the Middle East had been thus pegged to the Western standards.

West Asian countries had no focal point to look at Asia, which seemed isolated. Many of its countries were too weak or far away, with not much in common between East and West Asian countries other than culture and religion. This has dramatically changed due to systemic shifts and globalisation. Regionalism in the Gulf, for example, is under the influence of “Asianisation”, with much to learn from Asean’s regional mechanisms.

China is believed to lead this “Asianisation” of West Asia, since it has accelerated the pace of change. It is the major trading partners of at least 10 Middle Eastern countries, leaving a dramatic and significant footprint which in turn symbolises the partnerships between the Gulf and East Asia. One of the main drivers of “Asianisation” is that energy patterns have shifted eastwards. The United States is looking to become self-sufficient in hydrocarbons, and fracking has allowed the US and North America in general, including Canada, to bring much more of its own hydrocarbons into the market.

Asia, on the other hand, has been rising in demand amid albeit a fixed supply. One example of how West and East Asia could benefit from deeper relations would be in the case of Central Asia and East Asia. Hunger for energy in East Asia and the abundant supply in Central Asian states have pushed the two parties together.

Apart from China, there is the importance of India in the larger Asian context. There have always been cultural and historical links between Middle East and India. In recent years, the latter has been seen as a sleeping giant starting to discover its own interests in the Indian Ocean. The closer proximity allows for easier mobilisation of the “people-people relations”, which could account for a rise in broader trade and investments.

Competition

One aspect of this is major power competition, such as the relative decline of the United States as well as the relative rise of China. Next, Asian power competition sees brewing regional tensions. Asian democracies like India, South Korea and Japan beginning to form their own coalition to contain the rise of China. Lastly, Gulf competition and the resultant tensions have disabled the constituent states in the region from co-operating together to appropriately respond to challenges such as the Covid-19 pandemic.

Dr Wu Bingbing

Deputy Director, Institute of Arab–Islamic Culture, Peking University

Dr Wu touched on two concepts to define Chinese economic and political policy. Firstly, China’s political relations framework saw the emergence of a new pattern of international relations, focusing on partnerships rather than alliances. Its economic relations framework revolved around the vision of a community with a shared future for humankind. These frameworks converge with the shared political, social and economic objectives of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Co-operation between China and countries in the Middle East in light of the pandemic were various, with differing levels between China and the different Gulf states. Some notable examples included working with United Arab Emirates (UAE) to develop vaccines and testing of artificial intelligence to detect infected cases and China sent medical teams to Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

China also strived to develop bilateral strategic partnership networks with individual countries, establishing a high-level joint bilateral co-operation committee with Saudi Arabia, which includes its crown prince, Muhammad bin Salman. It also established joint committees with the UAE and Qatar at the ministerial level.

Apart from developing these bilateral relations, China did not aim to replace the presence of collective regional platforms. China–GCC free trade zones are arguably the most important aspect of the China–Mena relations economically. However, GCC competition and internal regional disputes have become the barrier preventing the China–GCC strategic dialogue from bearing fruit. Although unsuccessful, these efforts bring hope for future co-operation between the two parties. China and the Arab countries have agreed to increase the level of interaction between their leaders, possibly through organising a summit, the symbolism of which could deepen their relations.

Another possible problem for China–GCC relation would be what Dr Wu called the “supply chain issue”. Covid-19 has shown the dangers of depending solely on one country and the need to diversify states’ sources of supply for resources. To shift away from one region to another in search of resources doesn’t necessarily solve the problem. Oil prices have been relatively low even before the pandemic, and if the Middle Eastern countries do not remain competitive economically these failures would increase domestic tensions, especially amongst the youth who would want to improve standards of living in the future.

US–China relations are another element which complicate the China–GCC relations. Given the recent “cold war” between the US and China, developing relations with China could help push the GCC not to take sides. Since not choosing sides will allow both China and the GCC states to benefit from the increasing trade, it may seem like a plausible course of action.

Dr Sim Li-Chen

Assistant Professor, Zayed University

Dr Sim gave a general overview of the areas of co-operation between the GCC and Asean, and suggested new ideas for co-operation. The four main areas of co-operation were in the fields of counter-terrorism, energy trade, people exchange and non-energy ventures.

Given the existence of Islamic State-related terrorist threats in Asean in places like Indonesia and Philippines, there is a shared common vision between Asean and the Gulf to limit extremist activities where they occur. This resulted in the formation of the King Salman Center for International Peace set up by Saudi Arabia in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to address counter-terrorist interests shared by both states.

A key element that binds the GCC and the Asean countries is energy trade. Despite having oil rich countries, Asean is a net oil importing region. The dwindling reserves in Indonesia and Malaysia, combined with a growing demand for energy in the region, provide the necessary lubrication for GCC–Asean relations to grow. One thing that further prevents the development of hydrocarbon trade is the high reliance of Asean countries on coal, which is cheap and indigenous to the region. This reduces the demand for liquefied natural gas (LNG), oil and petroleum. So far, only Singapore has taken up roles of equity investment in Gulf energy fields and signed a free trade agreement (FTA) with the GCC. Intra-regional disputes have made FTAs difficult between GCC and countries like Malaysia. A changing dynamic of energy needs in the region could change the nature of energy trade between the Gulf states and Asean states moving forward.

People exchange, or remittance, play another important role in GCC–Asean relations. Several of the Gulf states depend on a large amount of labour from Asean countries, with 30 to 50 per cent of remittance originating from the GCC states sent to these Asean countries, through the employment of domestic workers.

The final aspect of GCC–Asean relations are non-energy ventures. With the Gulf states making efforts to diversify their economy, there is room for interaction in the realms of food security, cargo handling and Green Sukuks (Shari’ah compliant investments in renewable energy).

Dr Shareefa Al-Adwani

Assistant Professor, American University of Kuwait

Facing a world full of new obstacles and tensions, GCC relations and bilateral agreements have developed in many areas with South Korea. Dr Al-Adwani elaborated on three dynamics of this relationship, namely in terms of oil trade, digitisation and security co-operation.

The US dollar remains strong, and oil is priced in the dollar. For this reason, oil is expensive for many countries and the prices would thus decrease following the decreased demand during the course of the Covid-19 pandemic. On the other hand, even though the South Korean won has strengthened, it hasn’t translated into a higher demand from South Korea.

Russia and Opec states have agreed to reduce production of oil until further notice. Countries heavily dependent on oil trade need to anticipate a longer-term decreased demand and the need for economic diversification. It is thus important for Gulf states to ensure that there are few disruptions in the supply chain between them and South Korea and also that there are alternatives in place.

Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, face-to-face interactions have become difficult and economic activity is hindered all around the globe. The pragmatic approach of continuing relations digitally is becoming increasingly accepted as a compromise to contain the pandemic while maintaining productivity in the workforce. The use of emails, online meetings and webinars is becoming normalised, and the GCC should have public sectors occupied by people who are digitally literate. Among the GCC states, many areas not ready for digital transformation. They thus need to begin their training now to follow up with international and domestic plans. In this respect, working with countries like South Korea may prove beneficial.

Given recent political tensions around the globe, especially the US–China “cold war”, South Korea finds itself stuck in the middle. It has learned that it cannot afford to ignore or indulge the American regime and stay diplomatically friendly with both sides. Thus, bilateral relations might move its focus away from these major powers and towards SK–GCC relations. The GCC may have a lack of will to do this though, since the tendency is to focus on the more traditional notion of security. However, Dr Al-Adwani believed they should also focus on human security considerations amid the current Covid-19 situation.

Notions of security is further expanded when considering other external shocks like the breakdown of software. A strong cybersecurity is required in this digital era, which the GCC may be lacking. Now should be a time of increased demand from the GCC for better technological equipment and software, and these partnerships should continue to develop beyond traditional ideas of security.

Dr Satoru Nakamura

Visiting Scholar, Gulf Research Center, Qatar University

According to Dr Nakamura, a brief summary of Japan’s relations with the Gulf is characterised by interdependence, multiculturalism, defensive realism, constructive engagement, shared values and respect for monarchies.

There are two major factors that will create new Japan–GCC relations in the future: Japan’s two major global strategies and the socio-economic changes taking place in Japan.

Japan’s grand strategy involves two major global strategies, one in the Indo-Pacific regional formation and the other being the expansion of free-trade zones (FTZ). Japan is already in the centre of the largest FTZ in the world, a trans-Pacific partnership with 11 Pacific countries which came into effect in December 2018. Dr Nakamura mentioned that a nationwide inquiry into industry in the region has indicated that many Japanese businesses now view India as the most promising new overseas investment outlet. The expansion of FTZs introduces a new concept in Japanese foreign policy, and creates new chances for investment. Because of this, it may be plausible to believe that Japan–GCC economic partnerships may not be too far off in Japan’s grand plan.

The second factor that could create new Japan–GCC relations mentioned by Dr Nakamura are the various socio-economic changes in Japan. He elaborated some contradicting events in Japan which posed challenges to overcoming the Covid-19 pandemic. On one hand, many Japanese people, students in particular, felt a sense of responsibility to contain the pandemic. On the other hand, many business owners requested to return to regular economic activities too quickly. The Japanese state had to mediate between the two parties in response to the pandemic, resulting in four new types of socio-economic structures being built.

Firstly, there was the development of new healthcare and medical treatment. Two new medicines being rapidly developed by joint ventures in Japan, although with less aided government support than in other countries. However, Dr Nakamura believed that the sense of responsibility and voluntary initiatives of such joint ventures is key for Japan moving forward.

Secondly, Eastern economies were being accelerated. The quick adjustments made by the Japanese economy involve the increased usage by private entities of artificial intelligence and robots to operate their systems, which helped them maintain social distancing while keeping relatively higher levels of productivity.

Thirdly, Japan had been focused on local revitalisation. The pandemic has influenced policies to reduce congestion by promoting ideas to diffuse pressure from high-traffic areas. Japan had already promoted policies to revitalise local areas prior to the coronavirus pandemic, but now there is a new and more urgent strive for it.

The final socio-economic change in Japan came in the form of energy reforms. There are currently 100 municipalities out of 500 which have successfully created 100 per cent renewable energy systems, making them more self-reliant. The Japanese Ministry of Environment that it is feasible to achieve sustainable hundred percent renewable energy systems in all Japanese local areas, except several areas like Tokyo, which could drastically affect their demand for foreign energy resources. On top of that, Japan is the biggest investor in the world for the development of hydrogen energy, the market for which is expected to double every year after 2020 to reach and is forecasted to reach 1.6 trillion US dollars in 2050.

About the Speakers

Professor of International Relations

Durham University

Dr Wu Bingbing

Deputy Director

Institute of Arab–Islamic Culture

Peking University

Dr Li-Chen Sim

Assistant Professor

Zayed University

Dr Shareefa Al-Adwani

Assistant Professor

American University of Kuwait

Dr Satoru Nakamura

Visiting Scholar

Gulf Research Center

Qatar University

Professor Anoush Ehteshami is Professor of International Relations at Durham University, UK. He is director of the al-Sabah Programme and of the Institute for Middle Eastern & Islamic Studies.

Dr Wu Bingbing is an associate professor and deputy director of Department of Arabic Language and Culture in Peking University. He is also director of Peking University’s Institute of Arab–Islamic Culture. His research interests focus on politics of contemporary Middle East, China–Middle Eastern relations, Shi’i Islam and Iranian studies, and Islamic culture.

Dr Li-Chen Sim is an assistant professor at Zayed University in the UAE and a specialist in the political economy of energy in Russia and in the Gulf. Her research interests include Gulf–Asia exchanges, Russia–China relations in the Middle East, and Russia–Gulf interactions.

Dr Shareefa Al-Adwani is an assistant professor of political science in the Department of International Relations and the director of the Center for Gulf Studies at the American University of Kuwait.

Dr Satoru Nakamura is a professor at Kobe University and a specialist in the history and politics of Saudi Arabia, and security in the Gulf and the Middle East. He was a research fellow at Institut de Hautes Etudes Internationales et du Devèloppement in Geneva, a visiting scholar at the College of Law and Politics at King Saud University in Saudi Arabia, as well as a visiting scholar at the Gulf Research Center at Qatar University.