The sub-prime crisis of 2008 showed how the bursting of a housing bubble in the United States led to massive defaults on home loans, resulting in a major financial crash. Dubai provides another example: A bubble began forming in the early 2000s, due to a massive inflow of expatriates in search of job opportunities. This, in tandem with foreign investors attracted by the safe tax haven status of the emirate, sparked big increases in real estate prices. When the global financial crisis occurred, the flight of capital, and expatriates who lost their jobs, saw property prices in Dubai crash by 50 per cent or more in most areas, leading some highly leveraged flagship companies to struggle to repay their debt. In November 2009, Dubai asked for a debt standstill, an announcement that sent shock waves through international markets.

The recent surge in residential prices in Dubai after the Covid-19 pandemic mirrors, to a large extent, the episode of the 2000s. To prevent a similar conclusion, there is a need to assess the factors behind the current overheating market, and to set up a robust regulatory framework to ensure stability.

What follows is a look at growing residential prices and rents since 2022. This is followed by the market perception of risks for the Dubai government, based on data on credit default swaps, which are insurance premiums against a debt default. The way to mitigate risks will follow, with an analysis of the role of the Central Bank’s Loan-to-Value Ratio (LTV) tool, i.e., the maximum lending allowed as a percentage of the purchase value of the real estate, in tandem with the role of the Higher Committees that are entrusted with property market monitoring and oversight.

The Growing Property Bubble

As soon as Dubai recovered from the pandemic’s fallout, the inflow of expatriates, many of whom left the emirate after losing their jobs when Covid-19 struck, led to a housing shortage. In response, supply was increased to meet rising demand from both the incoming expatriates and investors (locals, resident expatriates, and non-resident foreigners), who saw a golden opportunity to buy, make money hand over fist, and exit before the cycle waned. Foreign buyers, in particular, were lured by the emirate’s status as a safe haven, with no personal income tax, relaxed social and visa rules, and a relatively high yield from investments, which remained above 7 per cent in recent years.

Given these conditions, the delivery of residential units increased from 31,000 in 2022, to 35,000 in 2023, and 73,000 thousand in 2025. Despite these big increases, supply could not match demand.

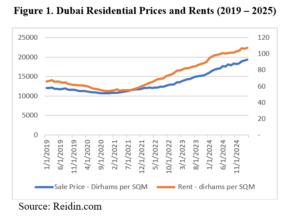

Historically, in similar situations, real estate prices go up first, influenced by broader market trends of supply and demand, investor confidence, and speculation, while rental rates tend to follow after a delay. In Dubai, however, data shows that rents began increasing almost simultaneously with the rise in purchase prices in the 4th quarter of 2021 (Figure 1), owing to massive government spending on infrastructure that offered huge job opportunities for expatriates, which perpetuated a cycle of unfettered demand for housing.

Figure 1. Dubai Residential Prices and Rents (2019 – 2025)

In terms of year on year increases, prices began to accelerate in August 2022, but the rate of increase began stabilising a year later. Rentals continued climbing until January 2023 before declining, although the increases remained in the double-digit range. By February 2025, rents had increased by 10.1 per cent, while prices went up by 16.8 per cent.

Figure 2. Y-o-Y Change in Dubai Residential Prices and Rents (%)

Potential Risks

According to some professionals, Dubai’s residential property market is becoming a seller’s one, as some investors are rushing to sell before it is too late. Already, some segments are becoming extremely volatile: For example, demand from wealthy Russians, which accelerated after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, may slow down as some of them move to less expensive destinations, such as Thailand and Indonesia. As a result of both a slowdown in demand and a spike in deliveries, which are expected to reach 210,000 units in 2026, Fitch, a rating agency, expects a drop in prices during the second half of 2025 and in 2026, but of no more than 15 per cent.

If the fall in prices remains within this range, and banks and homebuilders are able to absorb the lower prices, as Fitch stated in its report, overall risks can be mitigated, especially if property speculation is limited to 20 per cent, as stated by Dubai Land Department. Data on Credit Default Swaps from the government of Dubai show a declining trend since 2023, indicating that markets are either discarding the risks of a real estate crash, or are factoring in an implicit guarantee by the wealthy emirate of Abu Dhabi, which came to the rescue in 2009, when the Central Bank purchased US$10 billion worth of bonds issued by Dubai’s government.

UAE Sovereign Credit Default Swaps (2023 – 25)

In basis points

Source, Central Bank of the UAE’s Economic Review, Q2 2025.

Markets and experts can get it wrong though. As an example, the International Monetary Fund’s mission to the United Arab Emirates just a few months before the Dubai standstill request in 2009 failed to warn against the impending risks. More important, when the increase in residential prices is higher than the rise in rent, this indicates that the “bubble was largely driven by speculation” as argued by Paul Krugman. This has been the case in Dubai since July 2024 (Figure 2).

Therefore, it is not an overstatement to say the lights are blinking red, and a property meltdown reminiscent of the 2009 crash is very likely, although still preventable. To this end, urgent action is needed to review the regulations and the oversight mechanisms in place, in order to act before it is too late.

Regulations and Oversight

Following the real estate crash of 2008-2009, the UAE Central Bank issued Circular 31/2013 on Mortgage Loans Regulations, putting a cap on bank lending as a percentage of the value of properties — the so-called Loan-to-Value (LTV) ratio. For nationals’ first purchase, the cap is at 80 per cent if the value is equal or less than five million dirhams (about US$1.4 million), and 70 per cent if the value is higher. For a second home or investment property, the cap is 65 per cent, regardless of the value. For expatriates, the LTV is 5 percentage points fewer in each case. In 2020, an amendment to the Mortgage Loans Regulations was made, increasing the LTV ratio by 5 percentage points “in order to enhance the affordability of home purchases”. The amendment was among a vast array of measures taken by the federal authorities to counter the effects of the pandemic, known as the “Targeted Economic Support Scheme” (Tess). As the Central Bank started exiting Tess in December 2021, lenders returned gradually to pre-crisis requirements for downpayments: 15 per cent of the price of the property for locals, and 20 per cent for resident expatriates. But these rates are low by international standards. In Singapore, for example, the rate for a first loan is 25 per cent if its tenure is equal or less than 30 years, and extends until the borrower’s age of 65 or less, and 45 per cent otherwise.

To enhance Dubai’s status as a premier destination, the authorities reacted by establishing the Committee for Real Estate Investment Funds (REIFs) in 2024, which is expected to provide a well-regulated and transparent environment for these funds, thereby making them more attractive for institutional and retail investors. But more needs to be done to safeguard the sustainability of the property market. First, following the decision to abolish the Higher Committee for Real Estate Planning in 2023 (set up in September 2019 with the aim to avoid duplication and achieve a balance between supply and demand), there is a need for a more proactive role for the Dubai Land Department to oversee the implementation of the Real Estate Sector Strategy 2033, whose aim is to enhance market appeal and foster sustainability. Second, there is a need to monitor the shifting balance between supply and demand, and to undertake necessary measures.

Regional Impact

A stable real estate market in Dubai will benefit foreign owners, who own more than half of properties. The list is topped by nationals from India (US$21.3 billion), the United Kingdom (US$12.7), and Saudi Arabia (US$10 billion). Other major investors include those from Pakistan (US$8.6 billion), Iran ($5.4 billion), Canada ($4.1 billion), and Russia ($3.7 billion). This multi-national cross-section of investors enhances the emirate’s status as a top world destination for property. This is indeed a major reason why more attention ought to be paid to the knock-on effects of another bubble, as a new crash will shake the confidence of foreign investors, thereby compromising the work of the Committee for Real Estate Investment Funds.

The loss of confidence will also affect foreign direct investment in other fields, especially given the fact that Dubai is already leading in attracting FDI in other fields. In the cultural and creative industries, for example, the emirate surpassed major cities like London and Singapore in a 2024 ranking.

Putting the Pieces Together

Spotting a housing bubble and acting to stop it before it is too late is not easy. The Federal Reserve under Alan Greenspan failed to do so during his term in 2002-2006 despite looming evidence of a housing oversupply. For Dubai, the recent surge in property prices may pose serious risks similar to those of the 2008-09 crisis. Timely action is therefore needed to mitigate such risks. A proactive role of Dubai Land Department is needed for proper market regulation and oversight. At the federal level, the Central Bank of the UAE, which played a mostly reactive role in the previous crisis, needs to effectively contribute to mitigate the impending risks by using the macroprudential tools at its disposal.

* Mohamed Z. Bechri is former Principal Economist at the Central Bank of the UAE (2001 – 2022)

Image Caption: Indicators that the Dubai property market is headed for trouble are blinking red, and urgent action to review the regulations and oversight mechanisms in place is needed.